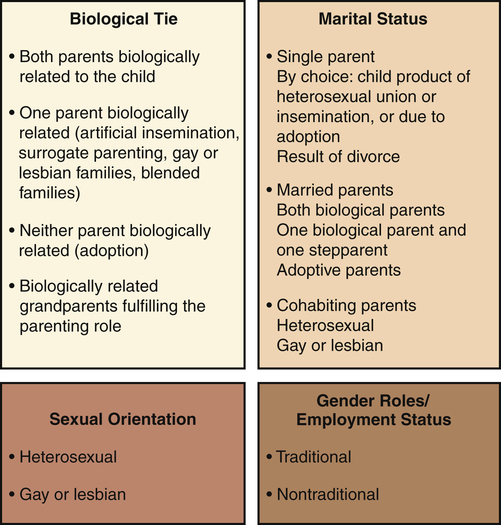

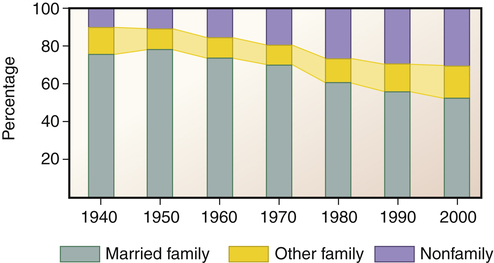

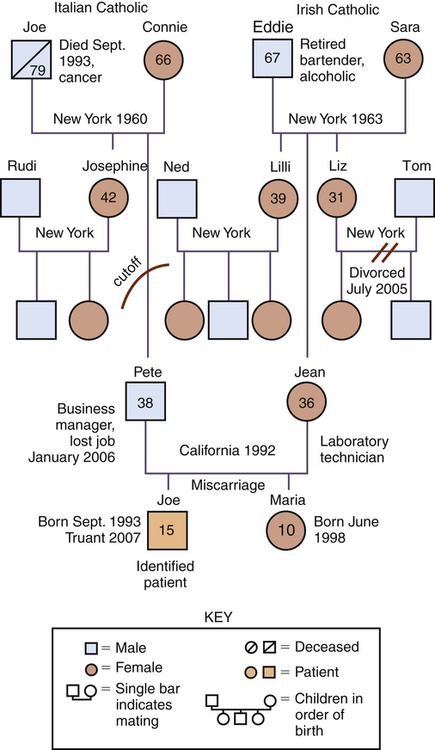

1. Describe the components of family assessment, including the use of the genogram. 2. Examine issues related to working with families of the mentally ill, including the competence model of care and psychoeducation. 3. Analyze the benefits and barriers to family involvement in the continuum of care. 4. Discuss how family members of a relative with mental illness are a population at risk. 5. Identify ways to collaborate with family advocacy organizations. • Assess the individual’s and the family’s needs and resources • Identify problems and strengths displayed by an individual and a family • Select interventions to promote positive coping strategies and adaptive functioning • Make decisions related to referrals to other appropriate resources The concept of “family” has evolved from the “two married heterosexual parents with several children of their own” to a variety of extended and creative nontraditional “family systems.” Nurses encounter many different types of families in their clinical work. This can challenge the nurse’s evaluation skills and perhaps the nurse’s own value system. Figure 10-1 presents four dimensions of parent status that can describe families in society: biological ties, marital status, sexual orientation, and gender roles. Although the definitions of family have become more fluid in recent decades, a family is usually defined in terms of kinship: individuals joined by marriage or its equivalent or by parenthood. • A nuclear family refers to parents and their children. • An extended family includes other people related by blood or marriage. • A household is a residence consisting of an individual living alone or a group of people sharing a common dwelling and cooking facilities. Over time in the United States, the number of households with married families has declined, whereas the number of nonfamily households has increased (Figure 10-2). • It completes important life cycle tasks. • It has the capacity to tolerate conflict and to adapt to adverse circumstances without long-term dysfunction or disintegration of family cohesion. • Emotional contact is maintained across generations and between family members without blurring necessary levels of authority. • Overcloseness or fusion is avoided, and distance is not used to solve problems. • Each twosome is expected to resolve the problems between them. Asking a third person to settle disputes or to take sides is discouraged. • Differences between family members are encouraged to promote personal growth and creativity. • Children are expected to assume age-appropriate responsibilities and to enjoy age-appropriate privileges negotiated with their parents. • The preservation of a positive emotional climate is more highly valued than doing what “should” be done or what is “right.” • Within each adult there is a balance of affective expression, careful rational thought, relationship focus, and caregiving; each adult can selectively function in the respective modes. • There is open communication and interactions among family members. Nurses have a professional responsibility to be aware of and be sensitive to aspects of family structures that are due to social, cultural, and ethnic differences (Box 10-1). Specifically, culture within a family determines the following: • The beliefs governing family relationships • The conflict and tensions in a family and their adaptive or maladaptive responses • The way outside events are perceived and interpreted • The beliefs regarding when, how, and what type of family interventions are most effective Family history information usually includes all family members across three generations (McGuinness et al, 2005). It is helpful to use a family genogram as the organizing structure for collecting this information. A three-generation family genogram is a structured method of gathering information and graphically showing the factual and emotional relationship data (McGoldrick et al, 2008). A sample genogram is presented in Figure 10-3. Drawing a family genogram in full view of the family on large easel paper or a blackboard broadens the family’s focus and facilitates an understanding of the family constellation. • Adaptation—use of family resources for problem solving when family equilibrium is stressed • Partnership—sharing of decision making and nurturing responsibilities by family members • Growth—physical and emotional maturation and self-fulfilment that is achieved by family members through mutual support and guidance • Affection—caring or loving relationship that exists among family members • Resolve—commitment to devote time to other members of the family for physical and emotional nurturing; includes sharing of time, space, and money The competence model of care focuses on family strengths, resources, competencies, values, and empowerment instead of dependency. It stresses the importance of treating people as collaborators who are the masters of their own fate and capable of making healthy changes (Marsh, 2000) (Table 10-1). TABLE 10-1 MODELS USED IN WORKING WITH FAMILIES From Marsh DT: Serious mental illness and the family: the practitioner’s guide, New York, 2000, John Wiley & Sons. • Focus is on growth-producing behaviors rather than on treatment of problems or prevention of negative outcomes. • Promotion and strengthening of individual and family functioning occur by fostering self-efficacy and other adaptive behaviors. • Definition of the relationship between the help seeker and help giver is based on a cooperative partnership that assumes joint responsibility. • Assistance is provided that is respectful of the family’s culture and congruent with the family’s appraisal of problems and needs. • Educational component that provides information about mental illness and the mental health system • Skill component that offers training in communication, conflict resolution, problem solving, assertiveness, behavioral management, and stress management • Emotional component that provides opportunities for catharsis, sharing, and mobilizing resources • Family process component that focuses on family strategies for coping with mental illness in the family • Social component that increases use of informal and formal support networks The educational program outlined in Box 10-2 is designed to meet the cognitive and behavioral needs of families. Psychoeducational programs for families should meet a range of needs and provide families with an opportunity to ask questions, express feelings, and socialize with each other and with mental health professionals.

Families as Resources, Caregivers, and Collaborators

Family Assessment

Characteristics of the Functional Family

Culture

Family History

Family APGAR

Working with Families

Competence Model

PATHOLOGY MODEL

COMPETENCE MODEL

Nature of model

Disease-based medical model

Health-based developmental model

View of families

Pathological or dysfunctional

Competent or potentially competent

Emphasis

Weakness, liabilities, and illness

Strengths, resources, and wellness

Role of professionals

Practitioners who provide psychotherapy

Enabling agents who help families achieve their goals

Role of families

Consumers or patients

Collaborators

Basis of assessment

Clinical pathology

Competencies and competence deficits

Goal of intervention

Treatment of family pathology or dysfunction

Empowerment of families in achieving mastery and control over their lives

Interventions

Psychotherapy

Strengthening of family competencies

Psychoeducational Programs