Introduction

The newborn check, which involves a thorough examination of the baby, is performed in the first few hours after birth and, with experience, is generally quite quick to perform. Once familiar with the appearance of the average newborn, anything unusual is easily noticed. Remember general observation of the baby’s condition and behaviour is as important as formal and systematic assessment.

It is important to involve the parents in their baby’s check, explaining all actions and reassuring them. If an abnormality is suspected, a clear and simple explanation should be given and a senior paediatrician contacted. Where relevant, transfer to a consultant unit from a midwife-led unit or home may be necessary for paediatric examination and discussion with the parents.

The midwife’s assessment of the baby at birth

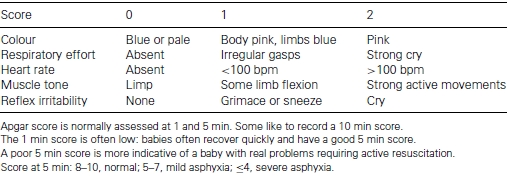

Most babies are born responding well and these babies should be given straight to their mother for uninterrupted skin-to-skin contact. Occasionally, a baby may be born with an obvious problem requiring a prompt response. The Apgar score is used as one assessment of the baby’s condition following birth (Table 5.1). Whilst the Apgar score is well established, it is not uncritically accepted and some have suggested abandoning it. (Patel & Beeby, 2004). The Apgar score may be helpful for deciding if resuscitation is required, but should not be relied on to determine the cause or prognosis of any hypoxic episode. If there are concerns about a baby’s condition, then paired (arterial and venous) cord bloods should be analysed which will give a clearer picture of the degree and duration of any labour hypoxia.

Colour

Caucasian babies should appear pink at birth, often with blueish extremities (peripheral cyanosis) for several hours following delivery. Babies with darker skins tend to have a much paler version of their parents’ skin tone with lighter extremities.

Possible problems are as follows:

- Blueness around the mouth and trunk (central cyanosis). It could indicate a respiratory or cardiac problem. Darker skin babies can look greyish white when cyanosed. If a baby appears cyanosed, oxygen should be administered, respiratory effort and heart rate assessed, and resuscitation should be initiated if required (see Chapter 21). Paediatric support should be requested.

- Very pale baby. Cardiac anomalies, anaemia or shock should be considered and resuscitation should be initiated if necessary.

- Facial congestion. A petechial rash seen as blue/mauve discolouration of the skin around the baby’s face. This can be result from a rapid delivery, cord around the neck or shoulder dystocia. The lips and mucous membranes should be pink. Do not confuse facial congestion with a more generalised rash resulting from thrombocytopenia or congenital infections such as toxoplasmosis, meningitis or herpes (Baston & Durward, 2001).

- Red baby. A plethoric appearance may be due to a large transfusion of placental blood, e.g. in twin-to-twin transfusion.

- Jaundice. Within 24 hours of birth, jaundice is abnormal and may be due to haemolytic disease/rhesus incompatibility or from a congenital infection, e.g. rubella, toxoplasmosis, herpes, cytomegalovirus or syphilis. Such infections may cause other symptoms including respiratory distress, rash, hypo/hyperthermia, hypoglycaemia and poor feeding (Hull & Johnston, 1999).

Table 5.1 Apgar score.

Respirations and cry

Not all newborns breathe immediately at birth nor do all cry at delivery, particularly if the birthing environment is calm, quiet and relaxed. Indeed anecdotal reports suggest that water birth babies do not always breathe immediately, but if the cord is not clamped and cut and is still pulsating at >100 bpm, the baby is likely to be receiving a good oxygen supply. However, some babies are seemingly inconsolable at birth. Once the baby is in the mother’s arms and settled in skin-to-skin, the baby will usually relax and stop crying, often opening its eyes and with patience will eventually root towards the breast.

Possible problems are as follows:

- A baby with persistent tachypnoea (respirations > 60/min in a term baby), grunting, nasal flaring or sternal recession is showing signs of respiratory distress. There are many causes including infection, meconium aspiration and cardiac problems. Refer to a paediatrician.

- A very mucusy baby who does not breathe following attempted inflation breaths will require gentle suction. Excessive secretions maybe a sign of oesophageal atresia.

- A healthy newborn cry is variable, but a distinctly high pitched or ‘irritable’ cry could indicate pain or cerebral irritation.

Heart rate

A baby’s heart rate can easily be ascertained by placing two fingers on the chest, directly over the heart, or by holding the base of the umbilical stump and counting the pulsating heart rate. Normal heart rate (HR) for a newborn baby should be 110–160 bpm.

Possible problems are as follows:

- Bradycardia (HR < 100 bpm) may be due to hypoxia. If other signs are good, the HR can recover quickly. If <60-bpm cardiac massage will be necessary (see Chapter 17).

- Tachycardia (HR> 160 bpm) may indicate a healthy response to a hypoxic episode. Again if other signs are good, it can recover quickly. It can however also indicate infection or a respiratory or cardiac problem. Refer for paediatric opinion if it persists.

Muscle tone

The newborn should have good muscle tone as well as normal reflexes and responses, such as opening its eyes and responding to external stimuli and touch. A baby who is floppy with poor muscle tone and little reflex response may have experienced significant hypoxia, or have a congenital abnormality, e.g. Down’s syndrome.

Measurements of the newborn

Weight

Following skin-to-skin contact and feeding, the baby should be weighed. The parents may wish to watch and take photographs. Ideally electronic scales are used for greatest accuracy, zeroed after positioning a warm towel. A kg/lb conversion chart is provided in the Appendix.

A baby weighing less than 2.5 kg is usually considered to be of low birth weight; a very low birth weight is below 1.5 kg. Ethnic origin-specific weight charts may be useful in avoiding inappropriately labelling a baby as small for dates (Chung et al., 2003).

A macrosomic or large baby is one with its weight above the 90th centile for its gestational age.

Both small and macrosomic babies are at risk of hypoglycaemia, so this should be noted and blood glucose estimates considered (Newel et al., 1997).

A baby born at <37 weeks is classified as preterm. Some babies may be both preterm and small for dates: these babies are at higher risk of problems, as growth retardation is a sign of placental insufficiency.

Length

Jokinen (2002) suggests, in the light of recommendations from the Joint Working Party on Child Health (Hall & Elliman, 2002), that a baseline length measurement remains important for assessment of a baby’s future growth and well-being. Fry (2002) emphasises the possibility of early detection of Turner’s syndrome if length measurement at birth is used as a baseline in relation to subsequent growth patterns. Timing of this measurement and equipment used has been under debate. In the first hours after the birth the baby may still be in a fetal position and so this may not be the optimum time to obtain such a measurement. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2007) recommends waiting at least 1 hour after birth. Jokinen (2002) notes that a tape measure has been proved to be unreliable (Wilshin et al., 1999). Various studies have shown that midwives can get improved results if using the more accurate supine length measurement tools, such as a roll-up mat (Jokinen, 2002). The normal range for a term baby is 48–55 cm (Seidel et al., 2006).

Head circumference

The head should be measured around the occipitofrontal circumference. The normal range for a term baby is 32–37 cm (Baston & Durward, 2001). Again there are arguments for delaying this measurement until the head has regained its shape following delivery and for the use of a metric insertion tape specifically designed for this purpose (Fry, 2002).

Vitamin K prophylaxis

Vitamin K is essential for the formation of prothrombin, which enables blood to clot. Haemorrhagic disease of the newborn (HDN) is a rare, potentially fatal, disorder that has been associated with low vitamin K levels. HDN may also be known as vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) since it can also occur later than the first week of life (Hey, 2003b). HDN/VKDB occurs most commonly in the first week: common bleeding sites are gastrointestinal, cutaneous, nasal and from circumcision (Puckett & Offringa, 2000). Late-onset bleeding occurring after the first week for up to 8 months is often associated with liver disease or malabsorption and is potentially more dangerous (Hey, 2003b).

Incidence and facts

- HDN/VKDB affects:

1 in 17 000 babies without vitamin K prophylaxis.

1 in 25 000 to 1 in 70 000 in babies who have had a single oral 1–2 mg dose at birth.

1 in 400 000 after a single intramuscular (IM) injection at birth (Puckett & Offringa, 2000).

- The incidence of haemorrhagic disease is significantly reduced in those babies receiving vitamin K at birth (Puckett & Offringa, 2000).

- Babies most at risk are those who are premature, unwell or have had traumatic deliveries.

- The Department of Health (DoH) (2005) recommends that all newborn babies are given vitamin K. More than 97% of UK babies currently receive it.

- Golding et al. (1992) suggested a tentative link between IM vitamin K and childhood leukaemia. Whilst the uncertainty cannot be completely resolved without a randomised controlled trial (which would be unethical), further studies show no association and it is concluded that Golding et al.’s findings were probably coincidental (DoH, 1998; Fear et al., 2003).

Vitamin K controversy

Doubt exists as to the optimal level of vitamin K in the newborn. Wickham (2000) suggests that since most babies have similar levels, this may not be ‘low’ but physiologically normal and desirable. Wickham proposes that the research suggesting that breast milk was low in vitamin K was carried out when feeds were restricted in length and frequency, resulting in reduced intake of fat-rich colostrum and hindmilk (where fat-soluble vitamin K is mostly found). In the early days and weeks following birth, babies build up a supply of vitamin K from feeding. Vitamin K is added to artificial milk. Totally breastfed babies have been found to be slightly more prone to late-onset haemorrhagic disease. However, it should be noted that in over half of the babies who develop late-onset HDN, there was an underlying cause, such as malabsorption or liver disease, contributing to vitamin K deficiency (Puckett & Offringa, 2000). It is suggested that term breastfed babies are mainly at risk only if early intake is limited or poor (Palmer, 1993;Hey, 2003b).

There is debate over relative benefits of IM or oral administration (Hey, 2003a). Intramuscular administration, although more effective, has the disadvantages of ‘trauma’ and poor acceptance by parents, as well as potential risks of very high vitamin K levels, whereas the disadvantages of oral preparations include increased cost, reliance on parent compliance and poorer absorption which may also (as the primary concern is HDN babies) affect babies with undiagnosed cholestasis (Sutor et al., 1999).

In conclusion, the RCM (1999) and the DoH (1998) both advocate that newborns should receive supplementary vitamin K but that the choice of administration (oral or IM) and whether to decline it altogether should rest with the parents. NICE (2006) recommends all parents are offered IM vitamin K for their baby and if this is declined should be offered an oral preparation as a ‘second-line’ option.

Top-to-toe check of the newborn

Each midwife will have a system for checking the newborn baby (top to toe and front to back is one way). Ensure the baby is not exposed naked for too long to avoid getting cold. The check can be performed in the cot or on the bed, wherever the mother is resting, so she can watch.

Head

Newborn babies can have very misshapen heads at birth. Parents should be reassured that the shape does quickly return to normal and that moulding (overriding of the skull bones) and caput succedaneum (oedema of the scalp) are common at birth. A swelling known as a cephalhaematoma (an effusion of blood beneath the periosteum of the cranial bone) is not present at birth but can develop in the hours/days following birth. The parents should be informed that it may take several weeks to resolve and may contribute to jaundice in a few days following birth, but is not usually serious.

Face

The appearance and symmetry of the face can be indicative of various conditions, e.g. Edward’s, Down’s or Turner’s syndromes. Baston & Durward (2001) recommend seeing both parents before commenting on any unusual appearance as the baby may simply have inherited familial traits.

Eyes

The eyes should be clear from discharge or inflammation, which if present within 24 hours of birth should be investigated as it could be a result of a gonococci infection which can lead to blindness. Other infections such as chlamydia and staphylococcal conjunctivitis usually occur a few days after birth. The eyes should be checked for the absence of cataracts (visible as a cloudy cornea), or a translucent iris, which can be a sign of albinism. Subconjunctival haemorrhages (red, crescent-shaped lesions on the conjunctiva) are not uncommon and usually resolve in a matter of weeks.

Ears

As with other areas of the body, the ears may have skin tags. These are usually small and are commonly tied with suture material by a paediatrician, until they drop off. Tags or dimpling are usually of no significance but occasionally indicate renal problems and should be documented and mentioned to a paediatrician. Low set ears can be associated with various disorders such as Patau’s/Down’s syndrome.

Mouth

Check the mouth for problems such as congenital teeth, which may need removing. A short, square or heart-shaped tongue may indicate tongue tie, i.e. a short tight frenulum. A very small number of babies with tongue tie may need a simple procedure to resolve the problem.

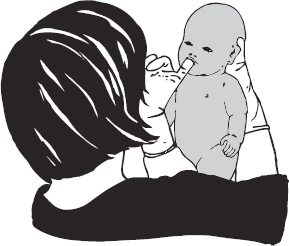

To check for cleft palate, insert a clean finger, fleshy side up and move across the roof of the mouth, and/or inspect with a light which may reveal a sub-mucous cleft, not easily felt (Fig. 5.1). Undetected clefts can cause feeding, and later speech, difficulties. Any baby with milk coming down its nose during a feed when not vomiting may have a cleft palate (Martin & Bannister, 2003).

Fig. 5.1 Finger inspection for cleft palate.