Evidence-Based Practice in Medical-Surgical Nursing

Rona F. Levin

Fay Wright

Learning Outcomes

1 Define evidence-based practice (EBP).

2 Describe the process of how best current evidence is used to make clinical decisions.

3 Explain how to use an EBP approach to identifying a clinical problem, issue, or challenge.

4 Formulate a focused clinical question about clinical practice.

5 List the steps of how to perform a systematic literature review to answer clinical questions.

6 Briefly describe two models of EBP.

7 Explain the steps of the evidence-based practice improvement (EBPI) model.

8 Discuss how the EBPI model can be used to guide a clinical practice improvement project.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview

All health care professionals need to understand and use an evidence-based practice (EBP) approach to practice. In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a report entitled Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. That report contained the following mandate: “All health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches and informatics” (p. 3).

In 2010, the IOM in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation published The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Among the four major recommendations is “Nurses should be full partners, with physicians and other health care professionals, in redesigning health care in the United States” (p. 3). The specifics of this recommendation include the need for nurses to be prepared to be full partners in health care improvement efforts. Aspects of this role include “taking responsibility for identifying problems and areas of system waste, devising and developing improvement plans, [and] tracking improvement over time …” (p. 3).

Definitions of Evidence-Based Practice

According to several nursing experts and the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN), EBP incorporates the best current evidence with the expertise of the clinician and the patient’s values and preferences to make a decision about health care (Levin & Lane, 2006; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). This definition was based on the work of Sackett et al. (2000), who had proposed three components of EBP—best evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values and preferences—as part of the definition of evidence-based medicine.

Ervin (2002) proposed this definition of EBP for nursing: “Evidence-based nursing practice is practice in which nurses make clinical decisions using the best available research and other evidence that is reflected in approved policies, procedures, and clinical guidelines in a particular healthcare agency” (p. 12). DiCenso et al. (2005) further extended this definition to include information about the patient’s clinical state and the setting or circumstances in which health care is being provided.

The EBP process is collaborative and involves all members of the health care team. This model is shared by many health care professions and is not unique to nursing. Therefore, although other professions might refer to the model as evidence-based medicine (EBM) or evidence-based social work similar to how DiCenso et al. (2005) specified the practice of nursing, the authors of this text refer to the model as EBP.

Steps of the Evidence-Based Practice Process

The process of EBP is systematic and includes several steps as presented by Sackett et al. (2000) in the context of practicing and teaching medicine.

1 Asking “burning” clinical questions

2 Finding the very best evidence to try to answer those questions

3 Critically appraising and synthesizing the relevant evidence

4 Making recommendations for practice improvement

5 Implementing accepted recommendations

Asking “Burning” Clinical Questions

Clinical questions are derived when clinicians do not have all the information they need to make the best possible decisions about patient care. A “burning” clinical question is one that usually arises in daily practice or when attending a class or reading a professional journal. The question may arise in relation to an individual patient, a group or population of patients, or a patient care unit or larger organizational area. An example of an individual patient question that a nurse might ask is, My older hospitalized patient who has been placed on fall precautions fell in the bathroom. What else could I have done to prevent this patient from falling, and what can I do to prevent her from falling in the future? At a group or population level, the nurse might ask, What are current best practices for assessing in the hospital patients’ risk for falls, and/or what are best practices for fall prevention in patients who are at risk for falls? At a unit or organizational level, the question might be, Is the current policy and procedure for assessing patients’ risk for falls and for implementing preventive practices based on the best available evidence?

Once you critically think about and pose a question about clinical practice, you will need to find out at what level the question needs to be answered (i.e., at the individual patient level, patient population level, or organizational level). If the latter two levels are where the problem exists, then begin to gather background information from the literature and internal evidence from your organization to describe the problem more fully (Levin et al., 2010).

One way you can begin to use EBP in your practice is to review the policy and procedure for a specific nursing practice in your clinical setting and determine what type of evidence was used as the basis for that policy and procedure. Does the protocol list references? What types of references are cited?

Once you have described the clinical practice problem and can focus on exactly what concerns you have, ask yourself whether the question is a background or a foreground question. A background question usually asks for a fact, a statement on which most authorities or experts would agree. For example, What is the etiology of congestive heart failure? What are the most frequently prescribed analgesics for the management of postoperative pain? The answers to these types of questions can usually be found in a textbook and are not controversial. A foreground question, on the other hand, usually asks a question of relationship and may be controversial. An example of this type of question is, What are the most effective interventions for treating venous leg ulcers?

Qualitative Versus Quantitative Questions.

If you are asking a foreground question, develop a more specific, detailed clinical question to guide your search for evidence. The two types of clinical questions are qualitative and quantitative. A qualitative question focuses on the meanings and interpretations of human phenomena or experience of people and usually analyzes the content of what a person says during an interview or what a researcher observes. Examples of qualitative questions are:

• What is the experience of having cancer like for young adults?

• How do older women respond to a residential move to assisted-living facilities?

• What are the differences in nurses’ work culture between acute care and home care agencies?

A quantitative question asks about the relationship between or among defined, measurable phenomena and includes statistical analysis of information that is collected to answer a question. Examples of quantitative questions are:

PICO(T) Format.

Nursing authors suggest framing clinical questions in a PICO (Cullum et al., 2008; Levin & Lane, 2006) or PICO(T) format. The PICO(T) format is outlined in Table 7-1. The major components of a focused clinical question are the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome, with an added time component when appropriate.

TABLE 7-1

EXAMPLES OF COMPONENTS OF PICO(T) QUESTIONS IN RELATION TO TYPE OF QUESTION

| THERAPY | ETIOLOGY | DIAGNOSIS | PREVENTION | PROGNOSIS | MEANING | |

| Population | ||||||

| Intervention | ||||||

| Comparison | ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Time |

The population indicates the specific group of patients to whom the question applies. This component is important because evidence that may support an intervention with one group of patients may not apply to another group of patients. For example, a fall prevention program for older adults who live at home may be very different from a fall prevention program for patients who attend a rehabilitation program. Be sure to think about the age, gender, ethnicity/race, and disorder to narrow your population of interest.

The intervention component pertains to the therapeutic effectiveness of a new treatment and may include (1) exposure to disease or harm, (2) a prognostic factor, or (3) a risk behavior or factor (e.g., the need for toileting to help prevent falls) (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). For example, one might compare a group of smokers to a group of nonsmokers to determine the relationship of smoking to bladder cancer.

The comparison component of the clinical question may be either the standard or current treatment or may be another intervention with which the innovative practice is compared. In the case of prognostic questions, the comparison may consider another factor or potential influence that could affect the outcome of the patient’s health. A preventive question might examine the absence of the risk factor as the comparison; for example, the need for toileting compared with no need for toileting to prevent falls.

The outcome component specifies the measurable and desired outcomes of your practice innovation, diagnosis, or prevention intervention. Outcomes may include measures of the results of an intervention (e.g., patients’ perception of pain, number of days spent in a hospital, or need for rehabilitative services). Or your outcome might focus on the sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test or nursing assessment tool (e.g., what is the best tool for assessing the risk for patient falls on an orthopedic unit?).

Fineout-Overholt and Stillwell (2011) advocated adding a time component or time frame to the focused clinical question. The question may include specifying within what time period one would expect the outcome(s) to occur. An example of a completed PICO(T) question is, What is the effect of adding hourly rounding to the standard falls protocol for the geriatric unit (patients 65 years or older) in hospital Y on the process of care provision (to be more specifically defined) and the outcomes of rate of falls, fall morbidity, and clinician satisfaction within a 3-month period?

Arriving at the focused clinical question is not an easy task, even for seasoned clinicians. Defining the specific question requires these three steps—identifying the problem, clarifying the problem, and focusing the question (Levin & Lane, 2006).

Finding the Best Evidence

Finding the best available evidence to answer a focused clinical question has been a challenge for clinicians and health care agencies. The major barrier that prevents nurses from engaging in evidence-based practice is lack of time. Other barriers include:

• Lack of value for research in practice

• Lack of understanding of organization or structure of electronic databases

• Difficulty accessing research materials

The health care system is addressing these challenges in many settings to improve the safety and quality of patient care. Many hospitals and community health care agencies are involved in promoting evidence-based practices and projects to reach national safety goals. An example of how staff nurses are essential contributors and collaborators on such projects is presented at the end of this chapter in the “Application of the EBPI Model to Clinical Practice” section.

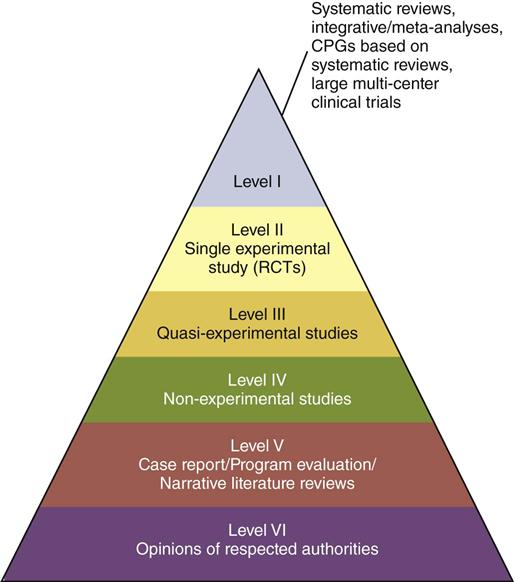

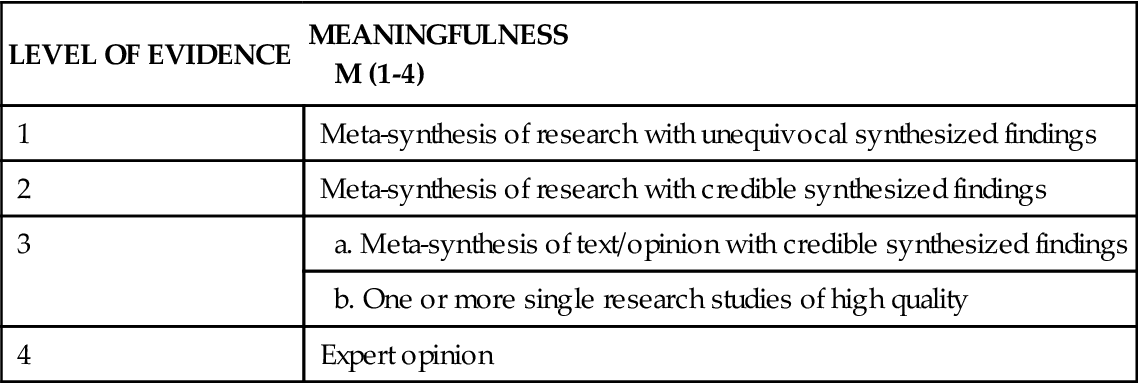

Levels of evidence refers to the status or rank of evidence. Most evidence hierarchies are pyramids with the highest level of evidence at the top (Fig. 7-1). The type of evidence needed depends on the nature of the clinical question—Is the question quantitative or qualitative? For example, if you are asking about the effectiveness of different types of compression bandages on healing of venous leg ulcers, you would want to measure the change in size of the ulcer as one indication of healing (quantitative). On the other hand, you might be interested in what the experience of having a chronic venous ulcer is like for women (qualitative). Each type of question requires different types and sources of evidence to find an answer. Table 7-2 provides an internationally accepted hierarchy for qualitative levels of evidence.

TABLE 7-2

JBI LEVELS OF QUALITATIVE EVIDENCE FOR MEANINGFULNESS*

| LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | MEANINGFULNESS M (1-4) |

| 1 | Meta-synthesis of research with unequivocal synthesized findings |

| 2 | Meta-synthesis of research with credible synthesized findings |

| 3 | a. Meta-synthesis of text/opinion with credible synthesized findings |

| b. One or more single research studies of high quality | |

| 4 | Expert opinion |

*From Joanna Briggs Institute. (2008). Reviewer’s manual. Adelaide, Australia: Author.

A preliminary evidence search entails identifying whether quality clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) exist to answer the clinical question. A clinical practice guideline is an “official recommendation” based on evidence to diagnose and/or manage a health problem (e.g., pain management). If these guidelines are of high quality and they contain the answer to your question, the search may be complete (Levin et al., 2007).

If the guidelines do not provide a sufficient answer to your question and/or they are not based on high quality evidence, you need to search the “Fantastic Four” databases:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree