CHAPTER 6 Evidence about diagnosis

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

Study designs that can be used for answering questions about diagnosis

Studies of diagnostic tests generally measure how accurately a test can detect the presence or absence of a disease by comparing the test with a reference test or ‘gold standard’. As we saw in Chapter 2, the best type of study to estimate diagnostic accuracy is a ‘consecutive cohort study’. This is a study that compares the test of interest with a gold standard test in every client who presents with a similar type of clinical problem in a particular setting over a particular time period. As we saw in Chapter 2, systematic reviews are even better than an individual study or trying to read all the studies that are available. Systematic reviews will be discussed further in Chapter 12.

Other study designs are also possible, such as a convenience sample of clients who have had both the test of interest and the reference test, or studies that compare the test results of the index test and the reference test in clients who are known to have the disease of interest (cases) versus the test results in clients who are known not to have the disease of interest (controls). As these studies do not enroll clients with the whole spectrum of disease that may be seen in clinical practice (for example, they may only include clients who have a ‘mild’ form of the disease of interest), these study types can lead to biased estimates of diagnostic accuracy. Case-control studies, because they enroll clients who clearly have or do not have the disease, are known to overestimate the diagnostic accuracy of a test.1

Clinical scenario (continued): Structuring the clinical question

As with clinical questions about the effectiveness of interventions, we can define the clinical question for diagnostic questions using the PICO format that was outlined in Chapter 2. There are often several possible questions than can be asked, so it is worth spending a few minutes to consider the question you wish to ask more carefully.

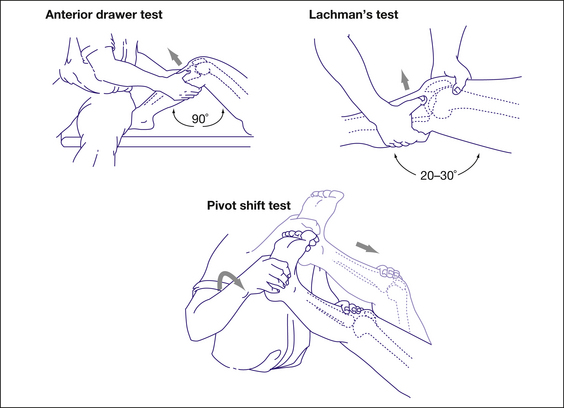

In the case of the 24-year-old footballer in the clinical scenario at the beginning of this chapter, you may be considering a meniscal injury, an injury to the anterior cruciate ligament or a soft tissue injury. You may want to define the population in the question broadly, such as in ‘all people’, or more narrowly, such as in ‘adults with a knee injury’. How narrowly you define the question may depend on whether you think that the test may perform differently in different sub-groups of clients. The disorders of meniscal injuries and anterior cruciate ligament injuries are the possible outcomes for the diagnostic test, and in this example we will focus on the physical examination for determining the presence of an anterior cruciate ligament injury. For anterior cruciate injuries, tests include the anterior drawer test, Lachman’s test and the pivot shift test2 (see Figure 6.1). Each of these parts of the physical examination of the knee can be the index tests. The comparator test should be the most accurate method of diagnosing these conditions. In general, the most accurate test for diagnosing intra-articular damage to the knee is arthroscopy. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also a highly accurate test for meniscal and ligament injuries of the knee and may be used in some studies because it is less invasive than surgery. Unless clients have a reasonably high probability of the disease or are considering surgery, it is difficult to justify performing surgery in clients to verify the results of physical examination, so many studies will not have used the results of arthroscopy or will only have included clients who are being scheduled for surgery. For this clinical question, both forms of investigation can be considered as the gold standard test.

Anterior drawer test

FIGURE 6.1 Description and illustration of the anterior drawer test, Lachman’s test, and the pivot shift test

Adapted with permission from Jackson J et al, Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care, Annals of Internal Medicine, 20032

Clinical scenario (continued): Finding the evidence to answer your question

As we saw in Chapter 3, one of the best options for finding diagnostic accuracy studies is PubMed Clinical Queries. If you are looking for studies on a particular test, you may select ‘diagnosis’ and ‘specific’, and type in the name of the test. This may be enough to find what you want. If you do not find anything with a specific search, you can then look for more studies by selecting ‘sensitive’ instead of ‘specific’. If the test is used for diagnosing more than one disease, you will also need to type in the name of the disease to narrow the search to only the disease that you are considering (for example, ultrasound AND breast cancer). In this scenario, the test is the physical examination of the knee. You could type in the names of the different types of test (such as anterior drawer), but it would take quite a while to search for each separate test.

Using the search terms (knee injury AND physical examination) and with the ‘diagnosis’ and ‘narrow, specific’ options selected in PubMed Clinical Queries, your search finds 70 articles. You find a systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination to detect anterior cruciate injury.3 As the purpose of this scenario is to demonstrate how to appraise a diagnostic study, a primary study, rather than a systematic review, will be chosen for appraisal. One of the largest and most recent studies included in the systematic review was an audit of 203 patients who were referred to orthopaedic clinics in Bristol by general practitioners or accident and emergency departments.4

Clinical scenario (continued): Structured abstract of the chosen article

Is this evidence likely to be biased?

As we saw in Chapter 4, for studies about the effectiveness of interventions it is important to critically appraise the diagnostic test studies that you find to determine whether the study is adequate to inform your clinical practice. As with the other types of study designs, the main elements to consider are: 1) internal validity (in particular, the risk of bias); 2) the results (the estimates of diagnostic accuracy); and 3) whether or how the evidence might be applicable to your client or clinical practice.

We will use the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist for appraising a diagnostic test study to explain how to assess the likelihood of bias in this type of study. The key questions to ask when appraising the validity of a diagnostic study are summarised in Box 6.1. The checklist begins with two simple screening criteria that, if not met, indicate that the article is unlikely to be helpful and that further assessment of potential bias is probably unwarranted.

BOX 6.1 KEY QUESTIONS TO ASK WHEN APPRAISING THE VALIDITY (RISK OF BIAS) OF A DIAGNOSTIC STUDY