Ethical knowledge development

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

Certain fundamental ethical principles are universal and unchangeable, but the interpretation and application of truth changes and different people arrive at truth by widely different methods. . . . Adults who are dominated by the opinions of the herd may be morally retarded. We do not act morally unless we act from a sense of conviction and reason, guided by our own conscience.

Isabel Stewart (1921–1922, pp. 906, 909)

The opening quote suggests that, although certain ethical and moral directives seem universal, when they are used in clinical settings, the ways in which to apply them are not always clear. Moreover, the quote assumes that a moral truth does exist, at least in given situations, and that knowing ethical and moral truth requires not only our conscience and conviction but knowledge of moral and ethical directives. According to Stewart, moral and ethical truths are not necessarily what everyone else believes.

Ethical matters can be complicated; what to do is often not clear, and the information needed to make a sound decision may not be available. For example, consider the ethical directive “do no harm,” which is a commonly understood ethical principle. On the surface, this may seem like a truth that is easily honored, but how is it applied in a clinical setting?

Consider the following example: Jill and Armando are expecting their first child, and they may be carriers of the gene for cystic fibrosis; however, they seem to be unaware that an opportunity for genetic testing exists. You know that, in this instance, genetic testing would confirm or negate their carrier status and that, should they be found to be carriers, the fetus can be assessed prenatally to see if he or she has inherited the genetic mutation from each parent. You also know that, if this fetus has inherited both genes, the child will most certainly develop the condition, but its severity cannot be predicted. You wonder if you should encourage Jill and Armando to undergo genetic testing. When considering this situation, you recognize that the parents are devout Catholics who likely would not want to terminate a pregnancy for any reason. Moreover, you know that there are risks to the fetus associated with prenatal diagnosis, should they choose it. In addition, you can provide no assurances about the quality of life of the child should he or she develop the disease, because the condition could be severe or more mild. Knowing this, you wonder if you should encourage genetic testing or not and if encouraging it would, in fact, be doing no harm.

According to the quote from Stewart, you will eventually resolve this ethical dilemma by considering the principle “do no harm” as well as by involving your own reasoning. When making your decision, a whole host of contextual factors will be considered, including legal or policy requirements for information disclosure, what you believe the parents’ response would be if genetic testing were strongly encouraged, and what you believe constitutes caring in this situation. You will make a decision, and whatever decision is made will be the best you can do given the circumstances. What the “right” decision is may never be totally clear. You understand that, in this and countless other situations, “do no harm” becomes a very complex and uncertain directive to enact.

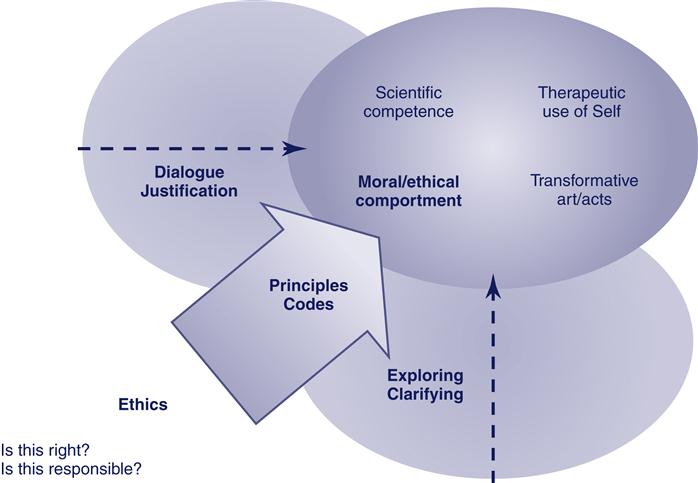

In this chapter, we focus on methods for creating ethical knowledge. Figure 4-1 shows the quadrant of our model that pertains to the development of this pattern of nursing knowledge. Nurses, regardless of setting, bring to practice the heritage of their own moral development and understandings as well as knowledge of ethical and moral practice obtained through formal education. With this background, as nurses practice and reflect on their practice, they begin to ask critical questions such as, “Is this right?” and “Is this responsible?” These questions set into motion the creative processes of clarifying values and exploring alternatives. As these questions are answered, knowledge that can be shared and used in practice, such as ethical principles and codes, is developed. Through the collective disciplinary processes of dialogue and justification, ethical knowledge is authenticated and understood in relation to practice.

According to our model, nurses who make use of ethical knowledge that has been strengthened through the authentication processes of dialogue and justification can be expected to increasingly practice with moral/ethical comportment. Moral/ethical comportment is the integrated expression of ethical knowing. In practice, further questioning occurs, and the stage is set for reinitiating the ongoing creative processes of clarifying values and exploring alternatives.

In this chapter, we begin with a discussion of the nature of ethical and moral knowledge in nursing. We then consider the dimensions of ethical knowledge development in nursing that are shown in the model.

Ethics, morality, and nursing

Clearly nursing is a profession that requires ethical knowledge to guide practice. Whether an individual is a seasoned nurse or a beginning student and whether a nurse working in a high-tech intensive care environment or in a rural and isolated elementary school, care outcomes depend on the nurse’s ethical knowing and morality. According to Levine (1989), all nursing actions are moral statements. We would add that all nursing actions also are ethical statements. But what constitutes ethical behavior? How is morality determined? These are difficult questions to answer, and, even when every effort is made to address ethical issues fully and appropriately, there is no guarantee that the right decision will be made.

Whether the business of ethics really is more complex today than it was historically is questionable, but certainly the need to make ethical decisions has always been part of the modern nurse’s role. Ethics is receiving renewed emphasis today, and nursing organizations are deliberately focusing on the need to attend to ethical issues. Certainly the complexity of today’s health care arena has raised questions about what is ethical behavior. Advances in technology, concerns about the proper care of marginalized groups, laws that regulate disclosure in health care and research practices, a focus on the rights of individuals in the health care system, and technologic advancements are but a few factors that have contributed to the unbelievable complexity of ethical decisions, thereby creating confusion about what is the morally right thing to do.

Ethics and morality are commonly interchanged terms that are sometimes used synonymously in the nursing literature. We see ethics and morality as being enmeshed, and we use both terms together in this chapter and elsewhere in this book. The distinction between ethics and morality reflects the tension between epistemology and ontology and the difficulty of separating what we know from who we are. In general, ethics relates to matters of epistemology or knowledge, whereas morality focuses on ontology or being. Ethics is a discipline that structures knowledge; it is a branch of inquiry that tries to make sense of what is right or wrong. Ethics, then, is more like head work, the products of which are things such as ethical principles, theories, rules, codes, and laws; lists of obligations or duties; and descriptions of moral and ethical behavior.

There are two branches of ethics: descriptive and prescriptive. Descriptive ethics is an empiric endeavor that systematizes what people believe ethically and how they behave in relation to those beliefs. For example, suppose you conducted a survey of your student peers and asked the following: (1) “Is it wrong to use purchased term papers about nurse theorists and their work to fulfill course requirements?” and (2) “Have you ever done this?” Collating and reporting their answers would be in the realm of descriptive ethics. Prescriptive or normative ethics is concerned with the “oughts” of behavior. With the use of cognitive reasoning processes that incorporate emotional and other nonrational sources of behavior, prescriptions for ethical behavior are put into language and set forth as theories, codes, duties, principles, and so forth.

With the use of the student peer survey example, you might reason how and why it is not permissible to purchase term papers to meet college course requirements by invoking a rule that deception is wrong. In this example, such a practice could be understood as deceiving faculty who expect you to do your own work. It also might be understood as self-deceit, because thoroughly learning about a theorist’s work is short-circuited by simply reading a paper rather than composing it. As a result of your logical thought processes, you might propose an addition to the student code of ethical behavior in your school. In this example, the use of descriptive ethics (i.e., what is, with regard to beliefs and actions about term paper purchase) might reveal that prescriptions for ethical behavior need clarification because they are being violated (i.e., that such practices are deceitful and therefore wrong).

Notice that, in this example, the need for ethical directives around purchasing papers on the Internet would not have been necessary or even seen as a possibility 50 years ago. In this text, our focus is on prescriptive ethics, but it is important to recognize the value of descriptive ethics for examining the nature of ethical knowledge in nursing.

By contrast, morality is expressed in behavior and grounded in values. If ethics is head work, you might think of morality as heart work that is expressed by doing. Morality refers to our day-to-day living expressions of what we believe to be good, beliefs that are firmly embedded in our character. When people consistently behave in concert with their values, moral integrity is shown. When moral behavior is blocked by situational factors in a way that matters to persons, moral distress results. For example, ethically you may believe that it is important to obey Provision 1 of the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics for Nurses, which states that you should practice with compassion and respect for the dignity and worth of every individual (“Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements,” 2005). However, because time constraints caused by a heavy patient load prohibit you from doing this in ways that really matter to you, you experience moral distress.

Morality is determined largely by situational and background experiences. Although people can appeal to ethical codes or principles to justify their actions, more often morality is shown on a less deliberative and conscious level. Daily expressions of belief about the right, the good, and the decent are filtered through lenses that are influenced by family, friends, religion, gender, and developmental stage. Thus, what constitutes moral behavior varies, and what is important in one society (e.g., being on time out of respect for others) may be unimportant in another. A religious affiliation associated with one community may provide a lens that justifies war; another affiliation may offer a lens that justifies pacifism.

Morality and ethics interrelate in that ethical knowledge can provide a basis or template for judging and evaluating moral standards and behavior. Conversely, moral or immoral behavior can provide a template for judging ethical knowledge. Consider the example of the United States Patients’ Bill of Rights in Medicare and Medicaid that was finalized in 1999 (“The Patients’ Bill of Rights in Medicare and Medicaid,” 1999). There are eight directives, which are summarized as follows:

Here is an example of ethical directives (ethical knowledge) being used to judge behavior as ethical or not. The right-to-privacy directive in the Patients’ Bill of Rights states, in part, that patients have the right to confidentiality. Suppose one day that, as you worked your shift in a long-term care facility, you overheard a well-meaning social worker talking with a nursing attendant in a hallway. The social worker was helping the attendant understand the nature of a resident’s dementia while visitors and other residents walked by. Because the resident who is demented was identified by name in the conversation, this activity clearly constitutes a breach of confidentiality as guaranteed in the Patients’ Bill of Rights. Because the right to privacy (the ethical directive) was breached, the behavior of the social worker and the attendant could be judged as immoral. Within some systems of ethical reasoning, the intent of the participants is important to ethical decision-making. In this instance, the social worker had the good intentions of helping the attendant to better care for the resident. Might the extent that the social worker’s actions would be judged immoral change if the participants knew better but just didn’t care? Regardless of how an incident such as this breach of confidentiality would be judged in relation to morality, it does violate a justifiable ethical directive. Several courses of action might be appropriate, including posting the Patients’ Bill of Rights in a public space as a reminder of its meaning or approaching the social worker and the aide and bringing to their attention the inappropriateness of their behavior in reference to privacy protections.

Conversely, here is an example where behavior is used to judge the adequacy of ethical knowledge. In the Patients’ Bill of Rights, another ethical directive states that patients must take more responsibility for maintaining good health. On your same shift in the long-term care facility, you notice that a newly employed nursing attendant has taken this directive to heart and is encouraging a resident with compromised cognitive function to take more responsibility for his self-care. Given the resident’s cognitive state, you understand that the attendant is asking the resident to do things that are physiologically impossible, and, as a result, the resident’s health is being compromised. In this example, the attendant attempts to behave morally in light of the directive but is unknowingly compromising other ethical principles that are generally accepted in health care, such as the prescription to do no harm. In this instance, the attendant’s moral expression of the ethical directive is helpful for realizing that the directive needs to be changed or clarified for persons whose cognitive function is not intact.

Knowing how to act ethically is often not so clear cut. Rather, moral behavior is fluid, it occurs in the moment without time for contemplation, and it depends on situational understandings and circumstances. For example, suppose you feel justified in providing information to a patient who asked you about alternative health care practices when you know that the primary physician is not willing to supply any information about their use. When the physician discovers that you have provided this information, she asks to talk with you about it. It turns out that both you and the physician feel that your respective actions are morally right. You feel that the patient has the right to know and thus use the precepts that surround a patient’s right to information to justify your action. The physician, on the other hand, provides reasons that indicate that her intent is to do no harm. The physician states that, in the past, she had given the same information to the patient, who had not acted on the information and subsequently became extremely anxious about making treatment choices. In short, your action of providing information on the basis of the patient’s right to know (autonomy) was judged as the right thing, whereas the physician, by withholding information, was also doing the right thing by protecting the patient’s vulnerabilities (doing no harm) on the basis of a reasonable knowledge of the patient’s condition. In this instance, the understanding that would arise from your conversation with the physician provides you with a perspective about the right thing to do that you can draw on in the future.

Sometimes when the moral positions of physician and nurse collide, both positions are reasonable, and both parties to the moral positions hold strong beliefs about their correctness. In these instances, there may be no clear answers about how to proceed, and it becomes important to identify the political processes that are operating. If the client’s welfare is the concern for both parties, then the nurse and the physician should be successful in engaging in dialogue that questions how right and responsible any decision is. Through this process, both the physician and the nurse (and the client, when feasible) can come to more fully understand the nature of the decision to be made and its potential outcomes. If the nurse’s or the physician’s attitude reflects more of a controlling or paternalistic position in relation to the client, other strategies may be warranted. In this instance, the nurse and the physician should recognize the nature of power imbalances and how they are sustained and seek avenues related to emancipatory knowing that fundamentally will undermine or circumvent paternalistic patterns of control.

Legal requirements may also create moral distress and ethical conflict. Although appeals to ethical knowledge can be used to challenge and justify morality, they do not supersede the law. For example, if you have a strong moral disposition toward counseling an underage woman about her options for birth control but such information is prohibited by state statute, an appeal to ethical knowledge (e.g., a code of rights) will not get you off the hook in a court of law. In these instances, you have the choice to break the law, engage in deliberate civil disobedience to make a political statement, or work within professional organizations and local political circles to change oppressive laws.

What it is important to understand is that you, as a nurse, may act morally in relation to strong ethical precepts and end up in a court of law because your actions were illegal. Historically, changes in ethical and moral traditions have been made because people were willing to risk their lives and their personal freedom and security to ensure a broad base of human rights for others. Taking such a risk to make a political statement and to press a community to consider ethical and moral alternatives requires courage and strong moral conviction. It is also the case that ethical principles, held historically, may eventually become law. An example is the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which passed into law directives that protect the privacy of personal health information (“Health information privacy,” 1996). With regard to this act, doing what was once only the right thing to do is now legally required.

Ideally, whatever constitutes moral behavior in nursing (elusive though that may be) needs to be in place, understood, and grounded in ethical knowledge that supports and justifies yet challenges that morality. Nursing, like other professions, has a unique set of values and a particular culture and practice that affects the ethical decision-making processes. The goal to be approached by nurses is moral and ethical coherence that is supported by laws and other societal contexts that do not prohibit but rather allow for the expression of nursing’s highest moral and ethical ideals.

Overview of ethical perspectives

Within philosophic ethics, various theoretic perspectives have emerged that attempt to set forth the foundation on which to base ethical action. These approaches to ethics have been important for nursing as it attempts to create an ethical perspective on practice. The four perspectives that appear commonly in nursing literature are briefly examined here: (1) teleology, (2) deontology, (3) relativism, and (4) virtue ethics.

Teleology and deontology

Teleology and deontology are two common labels that characterize ethical systems. Most ethical codes and principles as well as systems of ethical reasoning and decision making can be broadly classified into one of these two types. In teleology, what is right produces good. Teleologic systems look toward the ends produced by a course of action as the measure that determines the action’s goodness. What a right course of action yields is expressed in a familiar phrase: “the greatest good for the greatest number of people.” Taken to extremes, teleologic systems could be used to justify behavior that is deemed harmful to a societal group if the harm that was done produced good for the rest of society. With the use of teleology, one could justify stripping a wealthy person of personal assets for redistribution to those who are poor and thereby producing a greater good for a greater number of people.

In deontology, what is right may not necessarily produce a good outcome; in other words, deontologic systems separate right from good. In deontologic systems, ethically right actions may have an undesirable outcome, as expressed by the following phrase: “the end does not justify the means.” In deontologic frameworks for ethical decision making, knowledge forms such as external rules and codes determine what is right, regardless of the outcome produced. An extreme view of deontology is exemplified by someone who, because he or she is required by rule or precept to tell the truth, does the morally right thing and tells the truth, thereby causing great emotional distress to a client and that client’s family (i.e., a bad outcome). Deontologic systems suggest that the rules and the makers of rules are in charge of ethical decision making, whereas teleologic systems assign decision-making authority to persons who make reasoned judgments about what constitutes the greatest good. Both deontologic and teleologic systems focus on the individual as a decision maker who is autonomous in action.

Relativism

Relativism exists in many varieties and basically is the claim that what is morally and ethically correct varies across cultures and societies. In relation to ethical systems of reasoning, relativists would argue that universal generalities about what constitutes moral action cannot be made. In relativism, ethical behavior and moral viewpoints are justified by or are relative to any one of many viewpoints or standards; what is considered moral behavior and ethical knowledge is determined by the framework that is used when making a judgment, and no standard or viewpoint is privileged over any other.

In relativism, any one standard of morality is as good as any other, and all ethical precepts are equally true, assuming, of course, that they can be justified with the use of one acceptable framework or the other (Blackburn, 2005). A relativist position may argue that an ethical system grounded in deontology is just as good as one that is grounded in teleology. For relativists, ethical systems and morality depend on historical timing, the culture and language within which the justification system is embedded, and the particular group and individual subjects involved in decision making (Bandman & Bandman, 2001; Mappes & DeGrazia, 2006).

Relativism may be a comfortable position to take because it circumvents a responsibility to know how to behave with some degree of certainty in the face of moral and ethical dilemmas. Under the extreme relativist view, incorporating any idea of moral and ethical comportment into a knowledge development model becomes something of a nonissue; this is because moral and ethical comportment would be relative to every possible ethical situation, and thus standards for behavior could not be generalized to all nurses. Relativist claims also preclude the advancement of ethical knowledge because no standpoint for judging behavior is taken to be better than any other. However, some dimensions of relativism are useful and seem necessary in that nurses often face tremendous clinical complexities as part of ethical decision making that prevent knowing with much certainty what the best course of action is. Despite the fact that moral/ethical decision making involves uncertainties with regard to taking action that cannot be solved by a priori knowledge of what is moral and ethical, we believe we can move toward a shared idea of what constitutes moral/ethical comportment for nursing.

Virtue ethics

Virtue ethics introduces the character of the person as an important determiner of moral/ethical decision making. Virtue or individual character is unimportant within the frame of reference provided by deontology and teleology. If ethical behavior can be reduced to the application of rules or calculations of good, then character would be irrelevant. Character, however, determines how we perceive or frame situations, so a focus on the virtues of the nurse is critically important. Virtue ethics also offers a structure for moral/ethical comportment that can balance relativism by suggesting that a virtuous person will behave in a moral/ethical way. Virtue ethics allows for flexibility when approaching moral/ethical situations that deontologic and teleologic systems alone do not offer.

However, virtue ethics can be a particularly dangerous ethical system for a profession that is gendered in traditional female roles. Some focus on the cultivation of virtuous behavior seems important to ethical knowledge and knowing. Historically, however, for women to be virtuous meant to embrace a feminine ethic of being submissive, obedient, and self-sacrificing. It is important to question who defines what is virtuous and who benefits from the particular way in which the word virtuous is defined.

Our system for knowledge development includes aspects of both teleologic and deontologic perspectives. It also includes dimensions of relativism and virtue ethics. Although the knowledge forms include principles and codes, they are not taken to be infallible or to be adhered to at all costs. The creative processes of clarifying values and exploring alternatives can help to elucidate the situational contexts and decision-making frameworks that are important considerations for the modification of principles and codes. The authentication processes of dialogue and justification can function to temper rules and precepts and to sensitize them for different contexts. In addition, as the nurse acts, moral behavior and ethical knowledge are integrated with the other knowing patterns, including the personal knowing pattern, to create the best possible decision. This can in turn be further examined by questioning whether the action is right and responsible (rather than assuming that it is).

Our model incorporates a focus on virtues through the pattern of personal knowing, which grants the individual nurse the responsibility of examining what is virtuous. Emancipatory knowing suggests focusing on how and why particular virtues of nurses (e.g., caring, being on the job for patients despite heavy patient loads) may operate to maintain a problematic status quo (i.e., inadequate staffing that maximizes profits for hospital corporations rather than for caring nurses). The processes within the ethical knowledge quadrant help to ensure that, within the discipline, individual practitioners reflect on, discuss, and debate that which is virtuous in the context of nursing. As moral/ethical comportment is integrated in practice with other knowing patterns and then subsequently examined by the critical questions “Is this right?” and “Is this responsible?” we expect that the growth of the discipline toward action and reflection that are consistent with praxis will evolve.

Nursing’s focus on ethics and morality

The virtues of a dutiful nurse were the focus of much literature about ethics during the first half of the 19th century, as noted in Chapter 2. Reverby’s (1987) historical work underscores the nature of the nurse’s duty to care while being denied the means to effect or create an environment in which caring is valued and possible. In more recent nursing literature, there has been increasing interest in the concept of caring as a centrally important focus for the development of both empiric and ethical theory. Much of the literature regarding the ethics of care centers on the relative merits of an ethic of caring as compared with an ethic of justice and how moral behavior relates to both (Barnes & Brannelly, 2008; Bell & Hulbert, 2008).

Nursing’s focus on the caring perspective owes much to work that evolved from Carol Gilligan’s (1982) critique and challenge of Kohlberg’s (1976) theory of moral development. Kohlberg’s work staged moral development with the use of only male research subjects, and Gilligan challenged its validity as a normative template for judging moral development in women. Gilligan found that women tended to care about relational concerns that focused on the needs and feelings of major players involved in the dilemma. By contrast, autonomy in decision making was a central feature of Kohlberg’s theory.

Kohlberg’s theory supported a morality in which actors could remain detached from the situation and appeal to rules or calculations of good as a guide to action. An approach that emphasizes detachment and objectivity in ethical decision making has been linked to traditional medical ethics approaches and critiqued as inappropriate for nursing. Fry (1989), for example, has suggested that the context of nursing practice requires a moral view of the person rather than a theory of moral action or a system of moral justification. For Fry, caring as a moral value ought to be central to any theory of ethics. Others have pointed out that concerns about autonomy and justice that are central to biomedical ethics traditionally have been male-gendered traits. Not only do these imply a separate-from or autonomous stance toward ethical challenges, but they also may be inappropriate for nursing, in which gendered traits are typically female (Condon, 1992).

Feminists (Hoagland, 1990; Houston, 1990; Liaschenko, 1993; Noddings, 2003; Tong, 2008) have cautioned nurses about the alignment of moral decision making in women with care perspectives because of its potential to further entrench oppressive values. These authors point out the political reality of caring and urge caution lest we embrace a feminine—rather than a feminist—ethic (Liaschenko, 1993; Tong, 2008). Although it can become difficult to differentiate feminine and feminist ethics, writers such as Liaschenko suggest that a feminine ethic reflects the uncritical acceptance and embracing, often unknowingly, of traditionally feminine values that surround caring. Embracing a feminine ethic of caring means promoting as ethical the enactment of the virtues associated with caring: altruism, acceptance, loving unconditionally, and a host of other stereotypical feminine traits.

Although this type of caring may seem a perfectly good thing to do and to exemplify a very good way to be, such feminine virtues associated with caring may preclude nurses from understanding how this type of caring benefits the health care industry to the detriment of nurses’ salaries, working conditions, and social value. Whereas a feminine ethic is associated with the uncritical acceptance of stereotypical female caring as a template for judging moral behavior, a feminist ethic is associated with critically understanding the sociopolitical contexts that have gendered caring as feminine and why and how this is problematic in relation to changing the situation of nurses within the health care system. In short, a feminine ethic of caring proclaims the importance of caring as being consistent with female-gendered virtues.

A feminist ethic would recognize that morality and social lives are interconnected and that nursing’s lack of power shapes our morality by determining whose ethical vision is authoritative (Tong, 2008). Feminist ethics require critical analyses that help nurses understand how to create contexts that would, in fact, allow nurses to care. The caution to embrace a feminist rather than a feminine ethic, for feminist writers such as Liaschenko (1993), is a plea to understand how blind adherence to the feminine virtues of caring can in fact preclude caring by allowing for the continuance of conditions that exploit those who care.

We believe that nurses must be concerned with issues of both care and justice if nursing’s purposes are to be realized. Walker (1993) suggested that nurses’ moral expertise is not a question of mastering codes and laws but rather a matter of being architects of moral space within the health care setting and mediators in the conversations that are taking place. To do this requires paying attention to the vulnerabilities of an ethic of care as well as to the vulnerabilities of an ethic of justice. As Cooper (1991) explained, we must take seriously the moral demands of care in the development of ethics. Doing so requires radical responses and moral courage as well as political astuteness. Ethical choices should be guided not only by rules and principles but also by the thoughtful analysis of feelings, intuitions, and experiences (Noddings, 1999).

Dimensions of ethical knowledge development

Our view of ethics is in concert with Carper’s original conceptualization of the ethical pattern, which included dimensions of both morality and ethics intersecting with legally prescribed duties. Moreover, no single ethical or moral view is embraced, but there is a constant need to be vigilant about the sociopolitical context within which nurses function. According to Carper, “The ethical component of nursing is focused on matters of obligation or what ought to be done. Knowledge of morality goes beyond simply knowing the norms or ethical codes of the discipline. It includes voluntary actions that can be judged as deliberately right and wrong” (Carper, 1978, p. 20). When examining the nature of ethical knowing and knowledge, the following questions naturally arise: Toward what end should ethical knowledge be developed? What ought to be done in practice to earn the label ethical or moral? What values support nursing’s ethics and morality? Toward what clinical ends should ethical theories reason and ethical principles move us? What sort of moral development perspective should we embrace and encourage?

In the context of teleology, we might ask the following: How do we know what the greatest good is? In the context of deontology, the following question may arise: How do we know which rules are good and which are not? For virtue ethics, the following should be considered: Which virtues are worthwhile for us to cultivate? Such questions relate to the final value from which no others can be derived and which centers our knowledge development efforts and professional activities. Although we will not answer these questions, we do provide some guidelines for ways to create answers in your own situation. Because our model combines aspects of each of these positions, these are central questions that require thoughtful consideration.

As the dimensions of the model are discussed in the following sections, some answers will be provided, but additional questions will be raised. For us, the merit of ethical knowledge will be judged on the basis of the extent to which ethical codes and principles contribute to our collective ability to thoughtfully reflect and act in such a way that what we think and know is fully consistent with what we do. This implies increasing the reflective awareness or consciousness on the part of nurses as nursing is practiced. It implies a move toward action that is grounded in an open awareness and choice for both the client and the nurse: in other words, a move toward health. It implies a move to reduce the moral distress that nurses face as they encounter and negotiate ethical and moral dilemmas.

The pattern of ethics focuses on nurses’ usual day-to-day moral decision making. Ethics goes beyond what many tend to think of as ethics (i.e., the weighty, dramatic decisions that often involve end-of-life contexts or controversial political and social issues). Rather, important ethical knowing is used and created in everyday incidents and in the work of nurses (Liaschenko, Oguz, & Brunnquell, 2006). According to Thompson (2007), bioethics may be only marginally meaningful to most nurses; the language of bioethics deflects attention from the political organizations of care and the challenges of day-to-day nursing care. Ethical knowing in nursing is reflected in the decision to ignore a comment or to attend to it, in considering what to say and what not to say during everyday conversations, or in deciding whether to keep information to ourselves or reveal it. Ethical decisions that are made around a conference table by an ethics committee, although important, are not our major focus or the major domain of nursing’s morality and ethics. Rather, ethics arises from the work that nurses do and is about everyday uses of morality and ethical knowledge as expressed in moral/ethical comportment in typical practice settings. Nursing’s morality is, in large measure, an everyday ontology.

Critical questions: is this right? is this responsible?

In our model for knowledge development, ethical knowledge is generated with the following critical questions asked of ethical knowledge and moral behavior: “Is this right?” and “Is this responsible?” As you work as a nurse, this type of questioning is in the background whether you realize it or not. Without such questioning, you would be unable to make day-to-day moral/ethical moves.

We assume that nurses bring to their work some base set of values that guide their ethical decisions and moral behavior. As they work within the everyday world, their moral/ethical selves are challenged every day. For example, a nurse might wonder about the following: Should I reveal to an elderly woman that her family is cleaning out her apartment and do not intend to allow her to return home? Should I share my views about what is responsible childbearing with a young couple who discovers that they both have diabetes? Would this cause more harm than good? What would be gained? Who would gain? If you reflect for a moment, several instances in which you have faced such ordinary decisions should come to mind. You will probably notice that your decisions were made relatively quickly without obvious reference to ethical codes or principles and that you did wonder what was right and responsible. As you consider these questions in the moment of practice, you act in relation to knowledge that you have about what is ethical with consideration for other patterns of knowing. You will also reflect on the principles, codes, and other ethical knowledge forms that guided your actions apart from actual practice in an attempt to understand more fully what was and what should have been done in the situation.

Creative processes: clarifying values and exploring alternatives

As you or others inquire about how right and responsible your decisions are within your particular context, different perspectives on ethical decision making will become apparent. Clarifying values and exploring alternatives are the creative processes that begin to answer these questions. Simply stated, as you consider whether your moral/ethical behavior (as guided by disciplinary ethical knowledge) is right and responsible, you clarify the values that come into play as the situation unfolds, particularly those that create a dilemma. During this process, you are drawn to consider and explore various actions and options that flow from each value, which leads to the further clarification of the values themselves. Moreover, you and others can revisit and revise ethical knowledge forms to make them better guides for moral/ethical comportment.

Values clarification.

Values clarification processes deliberatively question and raise awareness of the personal values that undergird action. In this way, these processes have potential to improve the moral/ethical correctness or “rightness” of a decision. The specific values that give rise to a nurse’s moral/ethical decisions and actions (and subsequently ethical knowledge expressions) are often hidden. Values can be thought of as the assumptions or background information that create moral and ethical questions and actions. Values provide a lens that brings into focus certain aspects of a moral problem while at the same time distancing or blurring others. Values vary among individuals and reflect the contexts of our experiences with family members, friends, social institutions, gender boundaries, and age. The questioning of values with the use of formal techniques of clarification assumes that values may not always be “good.” It also assumes that there exists a disjunction between the values that we believe are important for influencing our actions and those that actually do influence what we do and say.

There are various techniques for values clarification (Bandman & Bandman, 2001; Catalano, 2008; Simon, Howe, & Kirschenbaum, 1995). Fundamentally, these processes involve the use of rational thought and emotional awareness to understand and examine the values that guide your actions. Approaches can involve the use of real or contrived dilemmas, group or individual work, self-analyses, interviews, or any number of other methods that free individuals to examine and embrace their values. The clarification of values is often an emotionally charged activity that involves deeply held personal beliefs. Individuals or groups who engage in values-clarification processes need an environment that allows for the freedom of value choices and for the affirmation of the values clarified. Regardless of the techniques used, values clarification is an individual process that seeks to unveil deeply held values that are often taken for granted. Values clarification is important because it emphasizes affective thinking and behavior-motivated choice and allows you to question how responsible your moral/ethical decisions are.

Various approaches for values clarification generally follow some basic general guidelines. First, it is important to select or create a moral/ethical dilemma that you and those working with you will emotionally relate to and that you will not see as fictitious to your practice. Although commonly used approaches such as “Which person would you throw from the sinking boat?” may suffice, we believe that more benefit is gained if the situations relate to actual or potential nursing practice. Second, it is important to focus on clarifying individual values that emerge from the process, regardless of the process used for clarification. When performing values clarification, there may be a tendency to avoid what is difficult. Lively discussions about what should be done are not a substitute for a deliberative focus on one’s personal values. A third guideline emphasizes writing about or listing personal values that emerge. Journaling about your values helps you to make values explicit and to clarify what the values are, and it also provides a forum for examining how and why values change. Because it is difficult to provide a public forum in which nurses can freely examine their values, journaling is a particularly important tool, especially when the moral/ethical dilemmas that are the focus for deliberation are derived from practice situations that you are likely to encounter.

Exploration of alternatives.

The exploration of alternatives is an important process for understanding the moral/ethical correctness of a decision. Unlike values clarification (i.e., an attempt to emotionally understand, clarify, embrace, and perhaps change individually held values), an exploration of alternatives seeks to more objectively understand and analyze the values that are inherent in a certain situation and the various actions that flow from those values. During the process of exploring alternatives, you examine how different courses of action that you might take flow from or challenge your values. As you explore what is or what could be happening morally and ethically in a situation, you begin to see alternative actions and even alternatives to your personal values. In addition, you begin to recognize the merits and pitfalls of different approaches to moral and ethical decision making. You strive to set aside your own values as much as possible and to view value structures—both your own and others’—from different perspectives. During the process of exploring alternatives, you strive to gain clarity on an issue, to examine various points of view both factually and logically, and to examine different approaches to resolving a dilemma.

As with values clarification, the situations that you choose for the exploration of alternatives arise from your practice. You explore the values that are important to the situation and the various actions that flow from those values. If factual evidence for one point of view is provided, that evidence is examined for accuracy. An ethical decision that is arrived at logically is then tested in some manner (e.g., by looking at its consistency with a principle or code for ethical behavior). However, when you are exploring alternatives, you are concerned not only with factual evidence but also with the preferences and beliefs of those who are involved in the situation. For example, when people are involved in caring for someone at the end of that person’s life, every individual involved will have personal beliefs and preferences about how best to care for the person who is dying. Each person’s personal beliefs and values regarding death, life, and life after death influence how he or she approaches the situation. The facts about the dying person’s physical condition, physiologic indicators that the end of life is near, and observable behaviors are all factors that influence the situation. However, there are a host of alternative actions that can be taken, even when all of the facts remain constant. As you explore all of the alternative actions that arise from the various values of those involved and the dilemmas that arise from competing ethical values, you gain insight and understanding of the situation and ultimately gain clarity about those actions that are right, good, just, and responsible.

As with values clarification, the situations that you choose for the exploration of alternatives arise from your practice. You explore the values that are important to the situation and the various actions that flow from those values. If factual evidence for one point of view is provided, that evidence is examined for accuracy. An ethical decision that is arrived at logically is then tested in some manner (e.g., by looking at its consistency with a principle or code for ethical behavior). However, when you are exploring alternatives, you are concerned not only with factual evidence but also with the preferences and beliefs of those who are involved in the situation. For example, when people are involved in caring for someone at the end of that person’s life, every individual involved will have personal beliefs and preferences about how best to care for the person who is dying. Each person’s personal beliefs and values regarding death, life, and life after death influence how he or she approaches the situation. The facts about the dying person’s physical condition, physiologic indicators that the end of life is near, and observable behaviors are all factors that influence the situation. However, there are a host of alternative actions that can be taken, even when all of the facts remain constant. As you explore all of the alternative actions that arise from the various values of those involved and the dilemmas that arise from competing ethical values, you gain insight and understanding of the situation and ultimately gain clarity about those actions that are right, good, just, and responsible.

Values clarification and exploration of alternatives with the use of ethical decision trees.

A number of sources suggest the use of decision trees as an approach to ethical decision making (Burkhardt & Nathaniel, 2007; Ellis & Hartley, 2004; Frame & Williams, 2005). Although the elements that constitute ethical decision-making trees vary somewhat, fundamentally they are depicted as flow charts or a series of ordered questions that begin with the identification of the ethical issue or problem. After the problem is identified, the user is guided linearly through a number of steps that, when followed, suggest an ethically correct decision.

Ethical decision trees call for the gathering of facts about the situation in relation to the ethical framework that is being used. Options are considered, situational factors are identified, and an evaluation of various courses of action is required before a decision is proposed. Some decision trees prescribe, at least in part, the ethical framework to be used, whereas others expect the user to designate or choose the framework that is relevant to the situation.

Ethical decision trees are particularly useful when there is enough time to effectively think about and spell out the requisite details within the elements of the tree before a decision is made. Ethical decision-making trees reflect what Liaschenko and Peter (2004) identify as a disciplinary type of ethics: an ethics that suggests that the professional activities of nurses that are understood in a certain way are inherently moral. These authors suggest that approaches that limit what counts as a moral or ethical concern and that authorize how these concerns are resolved—as decision trees often do—incompletely reflect the complexity of contemporary health care (Liaschenko & Peter, 2004).

However, decision trees can be useful as a learning tool. Like the nursing process, ethical decision trees offer a system that, once learned, helps nurses to more quickly integrate the details that are involved in ethical situations and to make an appropriate decision. The trees also make the factors and processes involved in ethical decisions less opaque and help learners to understand what is and is not ethically justifiable.

Completing decision trees can be useful for values clarification and the exploration of alternatives. Case studies of ethical problems can be organized into decision trees rather than being discussed directly. Decision trees can be completed by individual participants and then examined with the use of questions for values clarification, such as those posted on the evolve website. In addition, as participants individually complete decision trees, details that are important to consider within various elements required by the tree (e.g., the consequences of an action) will not be self-evident. When placing details of an ethical situation within a decision tree, it is important to notice which details require deliberation before making a choice and which can go unquestioned.

During this process, individual values tend to be clarified. As different members of the group suggest what must be included as relevant, the validity of various views within the group is likely to be challenged. Some group members may notice that certain details were omitted that, in their view, should have been included. Others may not have even thought about certain details as being relevant, whereas still others in the group may offer reasons for omissions as well as for inclusions. As discussions and disagreements occur, underlying values are made more visible to individual participants within the group. In addition, when individuals separately or groups collectively reflect on the extent and conditions of their agreement with a completed decision tree, values are clarified and alternatives explored.

Finally, changing the details that are entered in the elements of a decision tree and noticing how it affects both the processes and the outcomes of decision making is a useful clarification technique. Similar processes can be used for exploring alternatives with the use of completed decision trees. Elements that are required within the trees as well as the details within completed trees can be questioned for underlying assumptions and conditions of context that have precluded the possibility of making some decisions. As participants notice the details within various elements as well as the elements themselves, the underlying values and how they are operating come to light.

Both values clarification and the exploration of alternatives are important processes for understanding the nature of right and responsible moral/ethical decisions in relation to the knowledge form that is generated. The juxtaposition of personally cherished but problematic values (from values clarification) and possible alternative values (from the exploration of alternatives) deepens an individual’s understanding of what is possible and what is necessary for nursing practice. When problematic value positions are challenged by a person taking notice of alternative positions that are possible within certain situations, personal values can change.

The creative processes of clarifying and exploring include—whether recognized or not—references to justice and care perspectives that involve ethical decision making as well as to ethical principles and codes that are consistent with the deontologic and teleologic perspectives. Within our model, then, exploring and clarifying processes occur when questions are raised about what is right and what is responsible behavior. Out of these creative processes, formal expressions of ethical knowledge are created and recreated, and the integrated expression of ethical knowledge in practice as moral/ethical comportment is promoted.

Formal expressions of ethical knowing: principles and codes

The formal expressions of ethical knowledge that we have identified are principles and codes, which are commonly used in nursing (Numminen & Leino-Kilpi, 2009). However, other forms do exist. Ethical knowledge may be sets of rules; statements of duties, rights, or obligations; theory; or laws. The Nightingale Pledge (which, we would like to add, was not created by Nightingale) and the Hippocratic Oath also are forms of ethical knowledge. An individual nurse or a group of nurses setting forth an ethical position for disciplinary use could put that position in the form of an article, a case analysis, or even a poem.

We have chosen principles and codes as generic forms of ethical knowledge because they are attainable and common forms of ethical knowledge in nursing. For example, the American Nurses Association has created a code of ethics for nurses (“Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements,” 2005). Nurses are also taught to operate within common forms of ethical knowledge, such as principles of autonomy and beneficence. We prefer to avoid associating ethical knowledge forms with theory to prevent confusion of the differences between ethical and empiric theories. Regardless of the form of ethical knowledge, we suggest that, eventually, it can be reduced to principles and codes, which are shorthand ways of expressing ethical knowing.

Integrated expression in practice: moral/ethical comportment

The integrated expression of ethics in practice is moral/ethical comportment. The term comportment basically refers to how people behave and, in this case, how they behave in relation to what they do morally and what they know ethically. Moral/ethical comportment requires the consideration of all other knowing patterns in the moment of practice. In the previously mentioned case of Jill and Armando, the nurse had to integrate her empiric knowledge of genetics; her personal feelings that Jill and Armando’s fetus ought to be genetically tested and the pregnancy terminated if both parents carried the gene for cystic fibrosis; her aesthetic knowing to be sensitive to how Jill and Armando might respond if offered genetic testing; and her emancipatory knowing that testing is expensive and that, unfairly, Jill was not eligible for insurance coverage because of a preexisting condition. As this and other information is considered during the moment of ethical decision making and the decision is made, the nature of one’s moral/ethical comportment becomes clear. How nurses act and the decisions that they make in the complex contexts of practice ultimately contribute significantly to the processes for the development of ethical knowledge (Doane, Storch, & Pauly, 2009).

Authentication processes: dialogue and justification

It is within the model’s processes of dialogue and justification that knowledge is more deliberatively examined with reference to the perspectives of justice and care. Through these processes, ethical knowledge is examined and refined, and it becomes part of the disciplinary heritage that individual nurses subsequently carry into practice. This knowledge is revisited and challenged as the need arises by asking the critical questions: “Is this knowledge right?” “Is it responsible?” With these questions, nurses consider whether disciplinary forms of ethical knowledge guide right and responsible ethical decisions. These questions engage the clarifying and exploring processes that we have described with the use of dialogue and justification.

Dialogue requires a community of those who are challenged by an ethical problem. They come together as a community, either face to face, online, or via exchanges published in the professional literature to examine established ethical perspectives, principles, and codes (Btoush & Campbell, 2009; Freysteinson, 2009; Quaghebeur & Gastmans, 2009). As a group, they strive to more fully understand alternative points of view. On some issues, they come to a point where they can accept, reject, or modify the knowledge form. On others, the dialogues continue over long periods of time.

Traditionally ethical knowledge forms have been examined for internal logic as a standard of validity. Although internal logic is important for coherence, it is an insufficient standard for establishing the value of ethical knowledge in nursing. With dialogue, ideally multiple voices over time will be integrated into justification processes. The choice of the word justification suggests no particular framework for establishing the value of an ethical knowledge form.

Justification processes for ethical knowledge forms in nursing can appeal to the authority of historical values associated with nursing, existing moral/ethical knowledge, currently held values, and values and moral knowing consistent with an envisioned future, to name but a few. For example, the value of caring might be cited as an important historical factor that can be used to justify caring in nursing; in other words, caring as a historically embedded duty justifies caring as a contemporary value. Principles of nonmaleficence or autonomy, which baccalaureate students are generally exposed to, might be called upon to justify ethical knowledge. In addition, an envisioned future may form a critical template against which to reflect ethical knowledge. This occurs when we question whether caring is an ethic that will help us to achieve professional autonomy and identity. It is assumed that the collective voice of nursing will be the best hope for the emergence of appropriate and productive justification frameworks as the basis for re-envisioning the form of ethical knowledge.

We have chosen an eclectic approach to forming and justifying ethical principles because we believe no single perspective is entirely useful for all situations. Rather, the more likely scenario is that multiple justification perspectives will be used. Care must be balanced with a concern for justice; rules must be used in the context of doing the least harm or benefiting people in some way. Read the example in Box 4-1 to consider how this process unfolds.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree