Chapter 6 Ethical issues in health promotion

Overview

In particular, the chapter focuses on the limits to individual freedoms and how these are balanced against the health of the community. The chapter outlines the key ethical principles of beneficence (doing good), non-maleficence (doing no harm), justice, telling the truth and respect for people and their autonomy.

The need for a philosophy of health promotion

Debate in health promotion has centred on discussion of practice and some attempts to develop a theoretical base. However, according to Seedhouse (1988), there has been little discussion concerning the philosophy of health and yet it is an essential part of the way in which we understand the world.

Health promotion involves decisions and choices that affect other people which require judgements to be made about whether particular courses of action are right or wrong. There are no definite ways to behave. Health promotion is, according to Seedhouse (1988), ‘a moral endeavour’. Philosophical debate helps to clarify what it is that one believes in most and how one wants to run one’s life. It can and does help practitioners to reflect on the principles of practice, and thus to make practical judgements about whether to intervene and which strategies to adopt.

Philosophy has three main branches:

Duty and codes of practice

Deontologists hold that there are universal moral rules that it is our duty to follow. Many of the philosophical discussions about the nature of duty are based on the theories of Immanuel Kant. The essence of Kant’s thinking is encapsulated in the categorical imperative which can help us to discover, through reason, if a rule or moral principle exists (Kant 1909).

The major features of Kant’s theory are:

Deontological theories make decision-making apparently easy because, as long as we obey the rules, then we must be doing the right thing, regardless of the consequences.

Many health care workers have codes of practice which set out guidelines for the fulfilment of duties. For example, doctors take the Hippocratic oath which requires them as a first principle to avoid doing harm. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2004) states the duty to respect life, the duty to care, and the duty to do no harm. Kant would have added ‘the duty to be truthful in all declarations is a sacred, unconditional command of reason, and not to be limited by any expediency’ (Kant 1909). The Society of Health Education and Promotion Specialists (SHEPS) includes these principles in its code of conduct:

But, as Sindall (2002) has argued, health promotion has not engaged in the kind of debate necessary to agree the principles, duties and obligations to which health promoters would need to agree to work in the field. Codes of conduct are simply devices offering a framework in which to practise. They do not help practitioners involved in the messy and complex everyday world of health care (Duncan 2008). For example, Article 3 of the nursing code (Nursing and Midwifery Council 2004) declares that the registered nurse, midwife or specialist community public health nurse must obtain consent before any treatment or care but the concept of informed consent is complex.

Consequentialism and utilitarianism: the individual and the common good

Health promotion raises many questions over its ends and means:

In Chapter 4 we saw that some writers have expressed concern over ‘social engineering’ in health promotion and think that government intervention has risked becoming government intrusion. Many interventions are justified as being in the interests of a ‘healthy society’, yet they may not have been requested or desired.

Ethical principles

There are four widely accepted ethical principles (Beauchamp & Childress 1995):

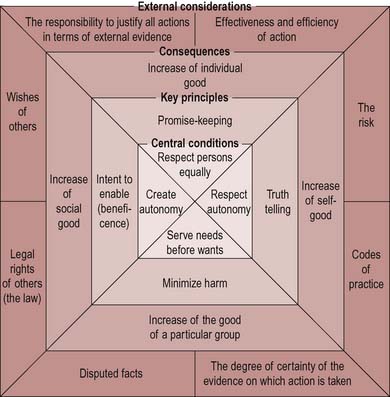

These principles provide a framework for consistent moral decision-making. However, situations rarely involve a single option, but can encapsulate increasingly complex and sometimes conflicting choices between these principles. Seedhouse (1988) has developed these principles into an ethical grid which helps provide health promoters with an easy-to-follow guide on which to ground their work on moral principles (Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 The ethical grid. The limit to the use of the grid is that it should be used honestly to seek to enable the enhancing potentials of people. From Seedhouse (1988).

BOX 6.1

BOX 6.1 BOX 6.2

BOX 6.2 BOX 6.3

BOX 6.3 BOX 6.4

BOX 6.4