Chapter 13 Characteristics of Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing, Ethical Issues Affecting Advanced Practice Nurses Ethical Decision Making Competency of Advanced Practice Nurses Evaluation of the Ethical Decision Making Competency Barriers to Ethical Practice and Potential Solutions Changes in interprofessional roles, advances in medical technology, privacy issues, revisions in patient care delivery systems, and heightened economic constraints have increased the complexity of ethical issues in the health care setting. Nurses in all areas of health care routinely encounter disturbing moral issues, yet the success with which these dilemmas are resolved varies significantly. Because nurses have a unique relationship with the patient and family, the moral position of nursing in the health care arena is distinct. As the complexity of issues intensifies, the role of the advanced practice nurse (APN) becomes particularly important in the identification, deliberation, and resolution of complicated and difficult moral problems. Although all nurses are moral agents, APNs are expected to be leaders in recognizing and resolving moral problems, creating ethical practice environments, and promoting social justice in the larger health care system. It is a basic tenet of the central definition of advanced practice nursing (see Chapter 3) that skill in ethical decision making is one of the core competencies of all APNs. In addition, the Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) essential competencies emphasize leadership in developing and evaluating strategies to manage ethical dilemmas in patient care and organizational arenas (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006). This chapter explores the distinctive ethical decision-making competency of advanced practice nursing, the process of developing and evaluating this competency, and barriers to ethical practice that APNs can expect to confront. In this chapter, the terms ethics and morality or morals are used interchangeably (see Beauchamp & Childress, 2009, for a discussion of the distinctions between these terms). A problem becomes an ethical or moral problem when issues of core values or fundamental obligations are present. An ethical or moral dilemma occurs when obligations require or appear to require that a person adopt two (or more) alternative actions, but the person cannot carry out all the required alternatives. The agent experiences tension because the moral obligations resulting from the dilemma create differing and opposing demands (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009; Purtilo & Doherty, 2011). In some moral dilemmas, the agent must choose between equally unacceptable alternatives; that is, both may have elements that are morally unsatisfactory. For example, based on her evaluation, a family nurse practitioner (FNP) may suspect that a patient is a victim of domestic violence, although the patient denies it. The FNP is faced with two options that are both ethically troubling—connect the patient with existing social services, possibly straining the family and jeopardizing the FNP-patient relationship, or avoid intervention and potentially allow the violence to continue. As described by Silva and Ludwick (2002), honoring the FNP’s desire to prevent harm (the principle of beneficence) justifies reporting the suspicion, whereas respect for the patient’s autonomy justifies the opposite course of action. Jameton (1984, 1993) has distinguished two additional types of moral problems from the classic moral dilemma, which he termed moral uncertainty and moral distress. In situations of moral uncertainty, the nurse experiences unease and questions the right course of action. In moral distress, nurses believe that they know the ethically appropriate action but feel constrained from carrying out that action because of institutional obstacles (e.g., lack of time or supervisory support, physician power, institutional policies, legal constraints). Noting that nurses and others often take varied actions in response to moral distress, Varcoe and colleagues (2012) have proposed a revision to Jameton’s definition: “moral distress is the experience of being seriously compromised as a moral agent in practicing in accordance with accepted professional values and standards. It is a relational experience shaped by multiple contexts, including the socio-political and cultural context of the workplace environment” (p. 60). The phenomenon of moral distress has received increasing national and international attention in nursing and medical literature. Studies have reported that moral distress is significantly related to unit-level ethical climate and to health care professionals’ decisions to leave clinical practice (Corley, Minick, Elswick, et al., 2005; Epstein & Hamric, 2009; Hamric, Borchers, & Epstein, 2012; Hamric, Davis, & Childress, 2006; Pauly, Varcoe, Storch, et al., 2009; Schluter, Winch, Hozhauser, et al., 2008; Varcoe, Pauly, Webster, & Storch, 2012). APNs work to decrease the incidence of moral uncertainty and moral distress for themselves and their colleagues through education, empowerment, and problem solving. The first theme encountered in many ethical dilemmas is the erosion of open and honest communication. Clear communication is an essential prerequisite for informed and responsible decision making. Some ethical disputes reflect inadequate communication rather than a difference in values (Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Ulrich, 2012). The APN’s communication skills are applied in several arenas. Within the health care team, discussions are most effective when members are accountable for presenting information in a precise and succinct manner. In patient encounters, disagreements between the patient and a family member or within the family can be rooted in faulty communication, which then leads to ethical conflict. The skill of listening is just as crucial in effective communication as having proficient verbal skills. Listening involves recognizing and appreciating various perspectives and showing respect to individuals with differing ideas. To listen well is to allow others the necessary time to form and present their thoughts and ideas. Understanding the language used in ethical deliberations (e.g., terms such as beneficence, autonomy, and utilitarian justice) helps the APN frame the concern. This can help those involved to see the components of the ethical problem rather than be mired in their own emotional responses. When ethical dilemmas arise, effective communication is the first key to negotiating and facilitating a resolution. Jameson (2003) has noted that the long history of conflict between certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) and anesthesiologists influences how these providers communicate in practice settings. In interviews with members of both groups, she found that some transcended role-based conflict whereas others became mired in it, particularly in the emotions around perceived threats to role fulfillment. She recommended enhancing communication through focus on the common goal of patient care, rather than on the conflicting opinions about supervision and autonomous practice. In other words, focusing on shared values rather than the values in conflict can promote effective communication. The second theme encountered is that most ethical dilemmas that occur in the health care setting are multidisciplinary in nature. Issues such as refusal of treatment, end-of-life decision making, cost containment, and confidentiality all have interprofessional elements interwoven in the dilemmas, so an interprofessional approach is necessary for successful resolution of the issue. Health care professionals bring varied viewpoints and perspectives into discussions of ethical issues (Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Piers, Azoulay, Ricou, et al., 2011; Shannon, Mitchell, & Cain, 2002). These differing positions can lead to creative and collaborative decision making or to a breakdown in communication and lack of problem solving. Thus, an interdisciplinary theme is prevalent in the presentation and resolution of ethical problems. The third theme that frequently arises when ethical issues in nursing practice are examined is the issue of balancing commitments to multiple parties. Nurses have numerous and, at times, competing fidelity obligations to various stakeholders in the health care and legal systems (Chambliss, 1996; Hamric, 2001). Fidelity is an ethical concept that requires persons to be faithful to their commitments and promises. For the APN, these obligations start with the patient and family but also include physicians and other colleagues, the institution or employer, the larger profession, and oneself. Ethical deliberation involves analyzing and dealing with the differing and opposing demands that occur as a result of these commitments. An APN may face a dilemma if encouraged by a specialist consultant to pursue a costly intervention on behalf of a patient, whereas the APN’s hiring organization has established cost containment as a key objective and does not support use of this intervention (Donagrandi & Eddy, 2000). In this and other situations, APNs are faced with an ethical dilemma created by multiple commitments and the need to balance obligations to all parties. Situations in which personal values contradict professional responsibilities often confront NPs in a primary care setting. Issues such as abortion, teen pregnancy, patient nonadherence to treatment, childhood immunizations, regulations and laws, and financial constraints that interfere with care were cited in one older study as frequently encountered ethical issues (Turner, Marquis, & Burman, 1996). Ethical problems related to insurance reimbursement, such as when implementation of a desired plan of care is delayed by the insurance authorization process or restrictive prescription plans, are an issue for APNs. The problem of inadequate reimbursement can also arise when there is a lack of transparency regarding the specifics of services covered by an insurance plan. For example, a patient who has undergone diagnostic testing during an inpatient stay may later be informed that the test is not covered by insurance because it was done on the day of discharge. Had the patient and nurse practitioner (NP) known of this policy, the testing could have been scheduled on an outpatient basis with prior authorization from the insurance company and thus be a covered expense. Viens (1994) found that primary care NPs interpret their moral responsibilities as balancing obligations to the patient, family, colleagues, employer, and society. More recently, Laabs (2005) has found that the issues most often noted by NP respondents as causing moral dilemmas are those of being required to follow policies and procedures that infringe on personal values, needing to bend the rules to ensure appropriate patient care, and dealing with patients who have refused appropriate care. Issues leading to moral distress included pressure to see an excessive number of patients, clinical decisions being made by others, and a lack of power to effect change (Laabs, 2005). Increasing expectations to care for more patients in less time are routine in all types of health care settings as pressures to contain costs escalate. APNs in rural settings may have fewer resources than their colleagues working in or near academic centers in which ethics committees, ethics consultants, and educational opportunities are more accessible. Issues of quality of life and symptom management traverse primary and acute health care settings. Pain relief and symptom management can be problematic for nurses and physicians (Oberle & Hughes, 2001). APNs must confront the various and sometimes conflicting goals of the patient, family, and other health care providers regarding the plans for treatment, symptom management, and quality of life. The APN is often the individual who coordinates the plan of care and thus is faced with clinical and ethical concerns when participants’ goals are not consistent or appropriate. In the acute care setting, APNs struggle with dilemmas involving pain management, end-of-life decision making, advance directives, assisted suicide, and medical errors (Shannon, Foglia, Hardy, & Gallagher, 2009). Rajput and Bekes (2002) identified ethical issues faced by hospital-based physicians, including obtaining informed consent, establishing a patient’s competence to make decisions, maintaining confidentiality, and transmitting health information electronically. APNs in acute care settings may experience similar ethical dilemmas. Recent studies of moral distress have revealed that feeling pressured to continue aggressive treatments that respondents thought were not in the patients’ best interest or in situations in which the patient was dying, working with physicians or nurses who were not fully competent, giving false hope to patients and families, poor team communication, and lack of provider continuity were all issues that engendered moral distress (Hamric & Blackhall, 2007; Hamric, Borchers, & Epstein, 2012). APNs bring a distinct perspective to collaborative decision making and often find themselves bridging communication between the medical team and patient or family. For example, the neonatal nurse practitioner (NNP) is responsible for the day-to-day medical management of the critically ill neonate and may be the first provider to respond in emergency situations (Juretschke, 2001). The NNP establishes a trusting relationship with the family and becomes aware of the values, beliefs, and attitudes that shape the family’s decisions. Thus, the NNP has insight into the perspectives of the health care team and family. This “in-the-middle” position, however, can be accompanied by moral distress (Hamric, 2001), particularly when the team’s treatment decision carried out by the NNP is not congruent with the NNP’s professional judgment or values. Botwinski (2010) conducted a needs assessment of NNPs and found that most had not received formal ethics content in their education and desired more education on the management of end-of-life situations, such as delivery room resuscitation of a child on the edge of viability. Knowing the best interests of the infant and balancing those obligations to the infant with the emotional, cognitive, financial, and moral concerns that face the family struggling with a critically ill neonate is a complex undertaking. Care must be guided by an NNP and health care team who understand the ethical principles and decision making related to issues confronted in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) practice. Ongoing cost containment pressures in the health care sector have significantly changed the traditional practice of delivering health care. Goals of reduced expenditures and services and increased efficiency, although important, may compete with enhanced quality of life for patients and improved treatment and care, creating tension between providers and administrators, particularly in managed care systems in which providers find that their clinical decisions are subject to outside review before they can be reimbursed. Ulrich and associates (2006) surveyed NPs and physician assistants to identify their ethical concerns in relation to cost containment efforts, including managed care. They found that 72% of respondents reported ethical concerns related to limited access to appropriate care and more than 50% reported concerns related to the quality of care. An earlier study of 254 NPs revealed that 80% of the sample perceived that to help patients, it was sometimes necessary to bend managed care guidelines to provide appropriate care (Ulrich, Soeken, & Miller, 2003). Most respondents in this study reported being moderately to extremely ethically concerned with managed care; more than 50% said that they were concerned that business decisions took priority over patient welfare and more than 75% stated that their primary obligation was shifting from the patient to the insurance plan. Although the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], 2011) may help with these concerns to some extent, the ethical tensions that underlie cost containment pressures and the business model orientation of health care delivery may continue. Technologic advances, such as the rapidly expanding field of genetics, are also challenging APNs (Caulfield, 2012; Harris, Winship, & Spriggs, 2005; Horner, 2004; Pullman & Hodgkinson, 2006). As Hopkinson and Mackay (2002) have noted, although the potential impact of mapping the human genome is immense, the challenge of how to translate genetic data rapidly into improvements in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease remains. To counsel patients effectively on the risks and benefits of genetic testing, APNs need to stay current in this rapidly changing field (a helpful resource for this and other issues is the text by Steinbock, Arras, and London, 2012). As one example, genetic testing poses a unique challenge to the informed consent process. Patients may feel pressured by family members to undergo or refuse testing, and may require intensive counseling to understand the complex implications of such testing; APNs are also involved in post-test counseling, which raises ethical concerns regarding the disclosure of test results to other family members (Erlen, 2006). Because genetic information is crucially linked to the concepts of privacy and confidentiality, and the availability of this information is increasing, it is inevitable that APNs will encounter legal issues and ethical dilemmas related to the use of genetic data. APNs may engage in research as principal investigators, co-investigators, or data collectors for clinical studies and trials. In addition, leading quality improvement (QI) initiatives is a key expectation of the DNP-prepared APN (AACN, 2006). Ethical issues abound in clinical research, including recruiting and retaining patients in studies, protecting vulnerable populations from undue risk, and ensuring informed consent, fair access to research, and study subjects’ privacy. As APNs move into QI and research initiatives, they may experience the conflict between the clinician role, in which the focus is on the best interests of an individual patient, and that of the researcher, in which the focus is on ensuring the integrity of the study (Edwards & Chalmers, 2002). Issues of access to and distribution of resources create powerful dilemmas for APNs, many of whom care for underserved populations. Issues of social justice and equitable access to resources present formidable challenges in clinical practice. Trotochard (2006) noted that a growing number of uninsured individuals lack access to routine health care; they experience worse outcomes from acute and chronic diseases and face higher mortality rates than those with insurance. McWilliams and colleagues (2007) found that previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries require significantly more hospitalizations and office visits when compared with those with similar health problems who, prior to Medicare eligibility, had private insurance. The PPACA, when fully enacted, will help improve access to quality care and decrease the incidence of these dilemmas. However, as noted, the escalating costs of health care represent ethical challenges to providers and systems alike, regardless of the population’s insurance status. The allocation of scarce health care resources also creates ethical conflicts for providers; regardless of payment mechanisms, there are insufficient resources to meet all societal needs (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2012; Trotochard, 2006). Scarcity of resources is more severe in developing areas of the world and justice issues of fair and equitable distribution of health care services present serious ethical dilemmas for nurses in these regions (Harrowing & Mill, 2010). A further international issue is the “brain drain” of nurses and other health professionals who leave underdeveloped countries to take jobs in developed countries (Chaguturu & Vallabhaneni, 2007; Dwyer, 2007). Allocation issues have been described in the area of organ transplantation but dilemmas related to scarce resources also arise in regard to daily decision making, for example, with a CNS guiding the assignment of patients in a staffing shortage, or an FNP finding that a specialty consultation for a patient is not available for several months. Whether in community or acute care settings, APNs must, on a daily basis, balance their obligation to provide holistic, evidence-based care with the necessity to contain costs and the reality that some patients will not receive needed health care. As Bodenheimer and Grumbach (2012) have noted, “Perhaps no tension within the U.S. health care system is as far from reaching a satisfactory equilibrium as the achievement of a basic level of fairness in the distribution of health care services and the burden of paying for those services” (p. 215). Finally, as APNs broaden their perspectives to encompass population health and increased policy activities, both essential competencies of the DNP-prepared APN (AACN, 2006), they will experience the tension between caring for the individual patient and the larger population (Emanuel, 2002). Caregivers are increasingly being asked to incorporate population-based cost considerations into individualized clinical decision making (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2012). Population-based considerations present a challenge to the moral agency of APNs, who have been educated to privilege the individual clinical decision. Over the last 30 years, the complexity of ethical issues in the health care environment and the inability to reach agreement among parties has resulted in participants turning to the legal system for resolution. A body of legal precedent has emerged, reflecting changes in society’s moral consensus. Ideally, moral rights are upheld or protected by the law. For example, the Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards established by the HHS mandate that health care institutions receiving federal funds provide services that are accessible to patients regardless of their cultural background (HHS, Office of Minority Health, 2001). These standards provide a legislative voice for the ethical obligation to respect all persons, regardless of their cultural background and primary language. In a different voice, the PPACA (HHS, 2011) has mandated that persons who can afford health insurance purchase it or pay a penalty, starting in 2014. According to this law, societal beneficence, in the form of limiting high expenditures on the care of uninsured persons, is preferred over individual autonomy (Trautman, 2011). APNs must use caution and not conflate legal perspectives with ethical decision making. In many cases, there is no relevant law and thoughtful deliberation of the ethical issues offers the best hope of resolution. In addition, looking to the judicial system for guidance in ethical decision making is troubling because the judicial aim is to interpret the law, not to satisfy the ethical concerns of all parties involved. In addition, clinical understanding may be absent from the judicial perspective. Involvement of the media may further confuse the situation, as was evident in the Schiavo case (Gostin, 2005). The legal guidelines in that case were clear; the Florida court system repeatedly upheld the right of Ms. Schiavo’s spouse to refuse nutrition and hydration on her behalf. However, advocacy groups, politicians, and Ms. Schiavo’s parents used the media to offer a variety of interpretations of the case and wielded political power to prevent removal of the feeding tube and to have it replaced twice after it was removed. Clearly, the legal perspective did not satisfy the moral concerns of all involved. Unfortunately, much of the publicity focused on the emotional experience of the parents fearing the loss of their daughter and not on careful consideration of the ethical elements. Sometimes, the law not only falls short of resolving ethical concerns, but contributes to the creation of new dilemmas. Changes in the Medicare hospice benefit under the PPACA (HHS, 2011) offer a clear example. Designed to prevent hospice agencies from enrolling and re-enrolling patients who do not meet criteria, the new regulations require a face-to-face assessment by a health care provider to recertify hospice eligibility at set intervals after the initial enrollment (Kennedy, 2012). Often, patients with dementia or another slowly progressive disease state who enroll in hospice experience an initial period of stability, likely because they have improved symptom management and access to comprehensive services. If this stability extends to the next certification period, the patient may face disenrollment. For the practitioner conducting the assessment, this creates the ethical dilemma of wanting to be truthful regarding the patient’s status and at the same time avoid removing a service that is benefiting the patient and family. There are a number of reasons why ethical decision making is a core competency of advanced practice nursing. As noted, clinical practice gives rise to numerous ethical concerns and APNs must be able to address these concerns. Also, ethical involvement follows and evolves from clinical expertise (Benner, Tanner, & Chesla, 2009). Another reason why ethical decision making is a core competency can be seen in the expanded collaborative skills that APNs develop (see Chapter 12). APNs practice in a variety of settings and positions but, in most cases, the APN is part of an interprofessional team of caregivers. The team may be loosely defined and structured, as in a rural setting, or more definitive, as in the acute care setting. The recent re-emergence of an interprofessional care model is changing practice for all providers (Interprofessional Collaborative Initiative [IPEC], 2011). Regardless of the structure, APNs need the knowledge and skills to avoid power struggles, broker and lead interdisciplinary communication, and facilitate consensus among team members in ethically difficult situations. The core competency of ethical decision making for APNs can be organized into four phases. Each phase depends on the acquisition of the knowledge and skills embedded in the previous level. Thus, the competency of ethical decision making is understood as an evolutionary process in an APN’s development. Phase 1 and beginning exposure to Phase 2 should be explicitly taught in the APN’s graduate education. Phases 3 and 4 evolve as APNs mature in their roles and become comfortable in the practice setting; these phases represent leadership behavior and the full enactment of the ethical decision making competency. Phase 4 relies on competencies required of DNP-prepared APNs; the knowledge and skills needed for Phases 3 and 4 should be incorporated into DNP programs. Although an expectation of the practice doctorate, all APNs should develop their ethical knowledge and skills to include elements of all four phases of this competency. The essential elements of each phase are described in Table 13-1. Phase 1 is the beginning of the APN’s personal journey toward developing a distinct and individualized ethical framework. The work of this phase includes developing sensitivity to the moral dimensions of clinical practice (Weaver, 2007). A helpful initial step in building moral sensitivity is understanding one’s values, in which students clarify the personal and professional values that inform their care (Fry & Johnstone, 2008). Engaging in this work uncovers personal values that may have been internalized and not openly acknowledged, and is particularly important in our multicultural world. Formal education in ethical theories and concepts should be included in graduate education programs for APNs. Although some beginning graduate students will have had significant exposure to ethical issues in their undergraduate programs, most have not. A 2008 U.S. survey of nurses and social workers found that only 51% of the nurse respondents had formal ethics education in their undergraduate or graduate education; 23% had no ethics training at all (Grady, Danis, Soeken, et al., 2008). APN students with no ethics education will be at a disadvantage in developing this competency because graduate education builds on the ethical foundation of professional practice. The current master’s essentials (AACN, 2011) do not address ethics education directly but include competencies in the use of ethical theories and principles. The Essentials of Doctoral Education for Advanced Nursing Practice (AACN, 2006) contains explicit ethical content in five of the eight major categories (Box 13-1). Even categories that do not explicitly list necessary ethical content imply it in referring to issues such as improving access to health care, addressing gaps in care, and using conceptual and analytic skills to address links between practice and organizational and policy issues. Exposure to ethical theories, principles, and concepts allows the APN to develop the language necessary to articulate ethical concerns in an interprofessional environment. It is important, however, that knowledge development extend beyond classroom discussions. Clinical practicum experiences also need to build in discussions of ethical dimensions of practice explicitly rather than assume that these discussions will naturally occur. In one study of the clinical experiences of graduate students from four graduate programs, only 4 of 20 students were identified as having experience with an ethical dilemma and only 2 of 22 preceptors noted any exposure to ethical dilemmas for students (Howard & Steinberg, 2002). The authors concluded that this apparent void in clinical education may have been a function of limited recognition of ethical decision making processes by APN students and preceptors. In another study, Laabs (2005) noted that 67% of NP respondents claimed that they never or rarely encountered ethical issues. Some respondents showed confusion regarding the language of ethics and related principles. In a later study, Laabs (2012) found that APN graduates, most of whom had had an ethics course in their graduate curriculum, indicated a fairly high level of confidence in their ability to manage ethical problems, but their overall ethics knowledge was low. These three studies provide compelling commentary on the need for Phase 1 activity in graduate curricula. As noted, education in ethical theories, principles, rules, and moral concepts provides the foundation for developing skills in ethical reasoning. Because the APN will apply these theoretical principles in actual encounters with patients, it is imperative that consideration of the context in specific situations be strengthened. A portion of graduate ethics education should involve discussion of typical issues encountered by APNs, rather than issues that receive extensive media attention but occur infrequently. Howard and Steinberg (2002) maintained that graduate curricula need to go beyond traditional ethical issues to encompass building trust in the APN-patient relationship, professionalism and patient advocacy, resource allocation decisions, individual versus population-based responsibilities, and managing tensions between business ethics and professional ethics. The latter three areas are crucial for developing the Phase 4 level of the ethical decision making competency. Continuing education programs are also effective and necessary forums in which current information can be provided in a rapidly changing health care environment. As technology changes and new dilemmas confront practitioners, the APN must be prepared to anticipate conditions that erode an ethical environment. Knowledge and skills in all phases of this competency depend on the application of current ethical knowledge in the clinical setting; ethical reasoning and clinical judgment share a common process and each serves to teach and inform the other (Dreyfus, Dreyfus, & Benner, 2009). Therefore, the importance of clinical practice cannot be overemphasized. Although ethical decision making in health care is extensively discussed in the bioethics literature, two dominant models are most often applied in the clinical setting. The first model of decision making is a principle-based model (Box 13-2), in which ethical decision making is guided by principles and rules (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). In cases of conflict, the principles or rules in contention are balanced and interpreted with the contextual elements of the situation. However, the final decision and moral justification for actions are based on an appeal to principles. In this way, the principles are binding and tolerant of the particularities of specific cases (Beauchamp & Childress). The principles of respect for persons, autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice are commonly applied in the analysis of ethical issues in nursing. The American Nurses Association (ANA) Code of Ethics for Nurses (2001) has endorsed the principle of respect for persons and underscores the profession’s commitment to serving individuals, families, and groups or communities. The emphasis on respect for persons throughout the code implies that it is not only a philosophical value of nursing, but also a binding principle within the profession. Although ethical principles and rules are the cornerstone of most ethical decisions, the principle-based approach has been criticized as being too formalistic for many clinicians and lacking in moral substance (Gert, Culver, & Clouser, 2006). Other critics have argued that a principle-based approach conceals the particular person and relationships and reduces the resolution of a clinical case simply to balancing principles (Rushton & Penticuff, 2007). Because all the principles are considered of equal moral weight, this approach has been seen as inadequate to provide guidance for moral action (Gert et al., 2006; Strong, 2007). In spite of these critiques, bioethical principles remain the most common ethical language used in clinical practice settings. The second common approach to ethical decision making is the casuistic model (Box 13-3), in which current cases are compared with paradigm cases (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009; Jonsen & Toulmin, 1988; Toulmin, 1994). The strength of this approach is that a dilemma is examined in a context-specific manner and then compared with an analogous earlier case. The fundamental philosophical assumption of this model is that ethics emerges from human moral experiences. Casuists approach dilemmas from an inductive position and work from the specific case to generalizations, rather than from generalizations to specific cases (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). Concerns have also been raised regarding the use of a casuistic model for ethical decision making. As a moral dilemma arises, the selection of the paradigm case may differ among the decision makers and thus the interpretation of the appropriate course of action will vary. In nursing, there are few paradigm cases of ethical issues on which to construct a decision making process. Furthermore, other than the reliance on previous cases, casuists have no mechanisms to justify their actions. The possibility that previous cases were reasoned in a faulty or inaccurate manner may not be fully considered or evaluated (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009). In spite of these concerns, the case-based moral reasoning used in casuistry appeals to clinicians because it mimics clinical reasoning, in which providers often appeal to earlier similar cases to make clinical judgments. Artnak and Dimmitt (1996) applied the casuistic model to an analysis of a complex case, concluding that the use of this approach allows fuller consideration of the contextual particulars of the case and provides a systematic approach for organizing and analyzing the facts of the case. An adaptation of this approach has been developed by Jonsen and colleagues (2010), sometimes referred to as the “four box” approach. These authors have advocated clustering patient information according to four key topics—medical indications, patient preferences, quality of life, and contextual features—and then using that information to resolve a dilemma. Because neither of these theoretical approaches have been seen as fully satisfactory, alternatives have emerged (see Box 13-3). Narrative approaches to ethical deliberation have evoked considerable interest (Charon & Montello, 2002; Nelson, 2004; Rorty, Werhane, & Mills, 2004). Narrative ethics emphasizes the particulars of a case or story as a vehicle for discerning the meaning and values embedded in ethical decision making. The argument is that all knowing is bound up in a narrative tradition and that all participants in ethical deliberations need the coherence and singular meaning given to a particular situation that only narrative knowledge can provide. Narrative ethics begins with a patient’s story and has some similarities with casuistry in its inductive particularistic approach. Critics of this approach have argued that although narrative is a necessary element in ethical analysis, it cannot supplant principle- or theory-based ethics (Arras, 1997; Childress, 1997). There is, however, recognition that careful consideration of patient’s stories can enlarge and enrich ethical deliberations. In commenting on narrative versus principle-based approaches, Childress (1997) noted that “We need both in any adequate ethics” (p. 268). As with casuistry, narrative-based approaches appeal to nurses, who find much of the meaning in their work through entering into the stories of their patient’s lives. Other approaches, such as virtue-based ethics, feminist ethics, and care-based ethics, provide alternative processes for moral reflection and argument (Beauchamp & Childress, 2009; Wolf, 1996). Historically, nursing ethics was virtue-based, with an emphasis on qualities necessary to be a virtuous nurse. Although this is no longer a dominant theme in nursing literature, it can still be seen. For example, Gallagher and Tschudin (2010) based their understanding of ethical leadership in professional values and virtues. The ethics of care has emerged as relevant to nursing (Cooper, 1991; Edwards, 2009; Lachman, 2012). The care perspective constructs the central moral problem as sustaining responsive connections and relationships with important others, and consequently focuses on issues surrounding the intrinsic needs and corresponding responsibilities that occur in relationships (Gilligan, 1982; Little, 1998). In this approach, moral reasoning requires empathy and emphasizes responsibilities rather than rights. The response of an individual to a moral dilemma emerges from important relationship considerations and the norms of friendship, care, and love. Viens (1995) reported that NPs she interviewed used a moral reasoning process that mirrored Gilligan’s model in the major themes of caring and responsibility. Although every ethical theory has some limitations and problems, an understanding of contemporary approaches to bioethics enables the APN to appeal to a variety of perspectives in achieving a moral resolution. In the clinical setting, ethical decision making most often reflects a blend of the various approaches rather than the application of a single approach. Although there is some danger in oversimplifying these rich and complex approaches, Exemplar 13-1 shows how they can be reflected in ethical decision making. A more thorough discussion of ethical theory is beyond the scope of this chapter, but the reader is referred to the references cited for more detail.

Ethical Decision Making

Characteristics of Ethical Dilemmas in Nursing

Communication Problems

Interdisciplinary Conflict

Multiple Commitments

Ethical Issues Affecting Advanced Practice Nurses

Primary Care Issues

Acute and Chronic Care

Societal Issues

Access to Resources and Issues of Justice

Legal Issues

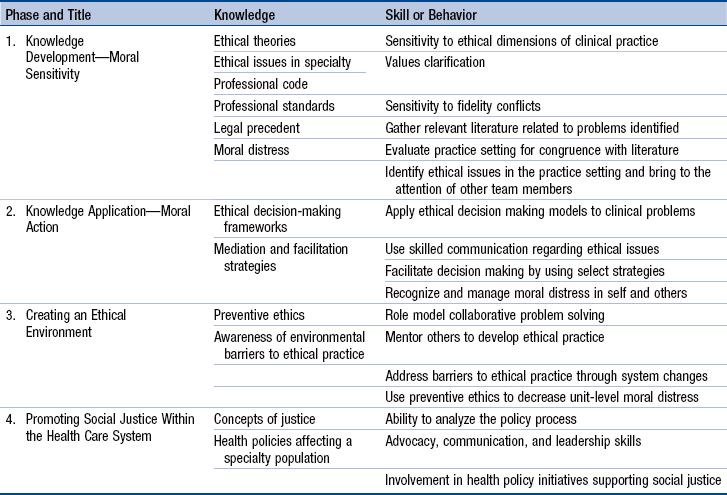

Ethical Decision Making Competency of Advanced Practice Nurses

Phases of Core Competency Development

Phase 1: Knowledge Development

Developing an Educational Foundation

Overview of Ethical Theories

Principle-Based Model.

Casuistry.

Narrative Ethics.

Care-Based Ethics.

Ethical Decision Making

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access