Chapter 16. Ensuring quality and the role of clinical audit

Janice Watson and Cathryn Battrick

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Discuss clinical governance, with reference to the key elements, activities and processes associated with the clinical governance framework.

• Consider what quality means in a health care context.

• Explore recent government policy on quality in the NHS.

• Review key quality tools and their use in providing quality services.

• Demonstrate a sound understanding of the audit process and its importance to the quality agenda.

• Examine the role of key agencies in assuring quality improvements in health care.

Introduction

In 1983, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that by 1990 all member states should have built effective mechanisms for ensuring the quality of patient care within their health care system, thus clearly identifying the global, central importance of quality in health care.

Arguably, quality in health care was first recognised by Florence Nightingale, who was a pioneer of systematic observation, standard setting and improvement of care and who clearly advocated the importance of quality in health care as early as the 19th century. During the Crimean War, Nightingale realised that admission to a battle hospital actually increased a soldier’s chances of death, so she set standards against which she measured practice. This process led to a drastic reduction in the rates of hospital-acquired infection and dramatically cut the mortality rate. Furthermore, Nightingale (1863) reiterated the need to collect data and measure outcomes in health care:

In attempting to arrive at the truth, I have applied everywhere for information, but in scarcely an instance have I been able to obtain hospital records fit for any purpose of comparison … They would show subscribers how their money was being spent, what amount of good was really being done with it or whether the money was doing mischief rather than good.

In 1959, the publication of the Platt Report, entitled ‘Welfare of Children in Hospital Report’ (Ministry of Health 1959), was an early attempt to raise standards in the care of sick children in hospital, although the aspirations of this report went largely unfulfilled. For several decades the wise words of Nightingale and the key features of the Platt Report went relatively unheeded, although voluntary organisations maintained an impetus for the need to improve quality of care. In particular, the work of Action for Sick Children, previously known as the National Association for the Welfare of Children in Hospital (NAWCH) made important contributions to the quality of care afforded children in hospital and introduced a ‘Charter for Children in Hospital’ in 1984. This charter encouraged nurse managers to monitor standards of care in children’s departments.

In general, the nursing profession had an interest in quality care, which grew with the development of the Royal College of Nursing and the RCN Standards of Care Project (Parsley & Corrigan 1999). From this work, nursing embraced the dynamic standards-setting system based on the Donabedian (1966) structure–process–outcome framework, but three main factors have resulted in an upsurge of interest in quality in recent years:

• Public expectations

• Recognition of the opportunities for improvement through good practice, but also following the rising rate of litigation and high-profile cases of major failures in the NHS, such as the Bristol Royal Infirmary heart surgery tragedy.

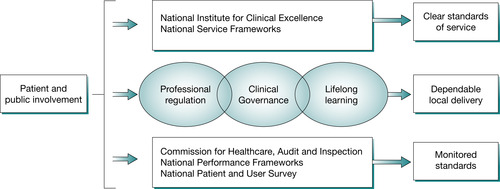

In response to these factors, the UK government introduced a significant set of reforms in the NHS, which shifted the focus towards quality of care and formed one of the main principles underpinning the incoming Labour government’s agenda for the NHS. In the White Paper ‘The New NHS: Modern Dependable’ (Department of Health (DoH) 1997), the government declared that the new NHS would have quality at its heart; quality was to be the driving force for decision making at every level of the service and the agenda for quality was set in the White Paper ‘A First Class Service’ (DoH 1998). This paper identified three main components for ensuring high-quality care:

• The setting of clear standards and the introduction of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the National Service Frameworks (NSFs).

• Delivering these standards at local level: clinical governance.

• Monitoring of standards: to be done by the Care Quality Commission: previously the Commission for Audit and Inspection (CHAI; previously the Commission for Health Improvement (CHI)), the NHS Performance Assessment Framework and the National Patient and User Surveys (Brocklehurst & Walshe 1999).

Figure 16.1 shows the relationship between these components; clinical governance being pivotal to this model.

|

| Fig. 16.1 The NHS quality framework. |

Defining quality in health care has been fraught with difficulties, with many examples of attempts to describe in detail what good quality is in any service. The work of Donabedian (1966) highlights the inherent dangers in this, stating that the criteria of quality are nothing more than value judgements. Basically, quality can be almost anything to anyone, based on their own values, beliefs and goals within both health care and society in general.

Quality as a concept is important in so far as we want to be able to measure it to improve it, and the identification of components of quality are one way in which this has been attempted. One such example is Maxwell’s six dimensions of quality (1984), which are:

• access to service

• relevance to need

• effectiveness

• equity

• social acceptability

• efficiency and economy.

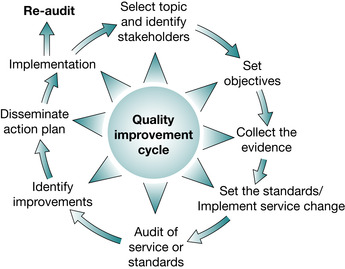

Importantly, the information gained from such performance measures is only meaningful if it is used to bring about improvement. It is therefore more useful to consider quality as a cycle of improvement (Fig. 16.2).

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

Student nurse Kelly Jones has read in her local paper that her local hospital has been awarded only two stars. She asks her assessor how these ratings are awarded.

Activity

Activity

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATIONStudent nurse Kelly Jones has read in her local paper that her local hospital has been awarded only two stars. She asks her assessor how these ratings are awarded.

Maxwell’s (1984) six dimensions of quality are reflected in the NHS Performance Assessment Framework, a set of performance indicators, or measures, that allow the performance of health authorities and NHS Trusts to be compared; some have been published in the form of league tables (Swage 2000). Individual trusts are assessed against these indicators and, depending on their score, a star rating is awarded, with five stars being the highest any Trust can achieve. These dimensions are:

• Health improvement and reducing health inequalities.

• Fair access irrespective of geography, socioeconomic group, ethnicity, age or gender.

• Effective delivery of appropriate health care that complies with agreed standards.

• Efficiency and the achievement of value for money.

• Patient/carer experience by assessing the way in which patients/carers view the quality of care they receive to ensure the NHS is sensitive to individual needs.

• Health outcomes of NHS care to assess the direct contribution of NHS care to improvement in overall health closing the loop back to the goal of health improvement (Pickering and Thompson, 2003, Scally and Donaldson, 1998 and Swage, 2000).

Activity

ActivityThe value of hospital league tables has been hotly debated in the media. Go to:

and choose the England ratings and Acute Trust indicators in the left hand menu. In particular, review the ratings for Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital and Birmingham Children’s Hospital:

and choose the England ratings and Acute Trust indicators in the left hand menu. In particular, review the ratings for Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital and Birmingham Children’s Hospital:

• What were their star ratings and do you think these are a fair way to represent the performance of any Trust?

• Do you feel the indicators give a snapshot of the true activity of the hospital and the quality of the services they provide?

• Do you feel these ratings help families make an informed choice about the quality of care they can expect to receive from any given Trust?

|

| Fig. 16.2 The quality improvement cycle. |

Quality is therefore represented as being a continuous process, which is an organisation-wide endeavour. Two such organisational approaches, which have been adopted within the NHS, are total quality management (TQM) and continuous quality improvement (CQI). CQI aims at embedding continuous quality improvement at all levels and across all services with the goal of achieving changes in practice that improve patient outcomes. Within the NHS, TQM and CQI are often used synonymously and interchangeably.

Total quality management

TQM is a business philosophy that was first introduced by Deming and Juran in the USA. It is a method of managing quality issues throughout every aspect of an organisation. Deming (one of the proponents of TQM) advocated a systematic approach to problem solving and promoted the PDCA cycle: Plan, Do, Check and Act. Juran, who is considered the father of quality, established a theory of quality management which evolved during the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s (Parsley & Corrigan 1999) and involves everyone and everything that happens in an organisation. Quality is therefore a continuous process expanding across departments and professional boundaries; it is:

… an integrated, corporately led programme of organisational change designed to engender and sustain a culture of continuous improvement based on customer orientated definitions of quality

(Joss & Kogan 1995 p 13)

Key TQM processes

• Focus on the needs and expectations of the market and consumers (i.e. health care and its patients).

• Achieve top quality performance in all areas of activity.

• Install whatever operating procedures – simple or complex – are necessary to achieve top quality performance.

• Critically and continuously examine the processes to reduce and remove non-productive activities, inefficiencies and waste.

• Develop and monitor measures of performance, set standards against which this performance is measured and identify required improvements.

• Understand the need for, and develop, an effective communication strategy.

• Develop a non-hierarchical team approach to problem solving and delegate responsibility for change.

• Develop good procedures for communication and feedback to staff at any level of good work.

• Continuously review the above processes to develop a culture for never-ending improvement.

The aim is to ‘get it right first time every time’.

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

Student nurse Jones has been reading an article in a nursing magazine, which has referred to TQM. She asks her assessor how TQM works in the NHS

Activity

Activity

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATION

PROFESSIONAL CONVERSATIONStudent nurse Jones has been reading an article in a nursing magazine, which has referred to TQM. She asks her assessor how TQM works in the NHS

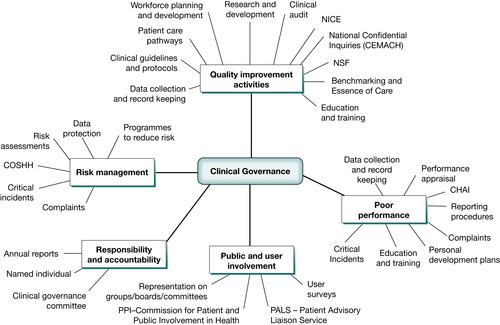

Clinical governance is an example within the NHS which reflects the TQM philosophy of managing quality issues. The key processes identified with TQM can be directly related to systems and processes associated with clinical governance. These include quality improvement activities like audit, data collection, and record keeping; clear lines of responsibility and accountability, risk management policies, procedures for identifying poor performance, and public and user involvement. So, you see, TQM is very relevant to the NMS.

Activity

ActivitySpend 20 minutes reflecting on your clinical experience and see if you can identify any quality processes that are or were evident in your day-to-day practice.

The rise of clinical governance

For health care to become more patient focused, and if quality improvements are to be made, then health care professionals need to embrace the wider aspects of care, which include:

• recognising the contribution of other colleagues from other disciplines

• organisational behaviour and change

• clinical audit

• working in teams.

A substantial shift in the culture of the NHS was required so that quality improvement became central to the work of the NHS, with an emphasis on collaboration rather than competition. To achieve this cultural shift the government determined that clinical governance would be used as a framework, with the patient–professional partnership at the pinnacle of a temple model supported by seven pillars (Scally & Donaldson 1998) (Fig. 16.3).

|

| Fig. 16.3 The temple model of clinical governance. |

Each pillar represents professional and managerial processes integral to quality improvement. Clinical governance acts like an umbrella under which all aspects of quality can be gathered and monitored and the WHO’s description of quality as being composed of four elements forms the basis for the development of clinical governance. These four elements are:

1. professional performance: technical quality

2. resource use: economic efficiency

3. risk management

4. patient satisfaction (Buetow & Roland 1999).

Clinical governance is defined as:

A framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which clinical care will flourish

(DoH 1998)

Clinical governance is to be the framework used to bring about a new culture, which places quality as central to the work of all in the NHS. It covers the organisation’s systems and processes for monitoring and improving services. This culture will be manifest in the ten C’s of clinical governance (Heard et al 2001):

• clinical performance

• clinical leadership

• clinical audit

• clinical risk management

• complaints

• continuing health needs assessments

• changing practice through evidence

• continuing education

• culture of excellence

• clear accountability.

Importantly, clinical governance encourages health care professionals to take control and demonstrate their ability to self-regulate and maintain public service accountability. Health care professionals are to take the lead in quality improvement strategies within a structure of increased external accountability. Clinical governance is part of a strategy for quality improvement in the context of a nationally coordinated programme of clinical guideline development with a nominated individual in each organisation responsible for clinical governance. Clinical governance is quality at a local level and focuses on processes of care, which include clinical decision making, appropriateness, clinical effectiveness and evidence- based practice (Pickering and Thompson, 2003 and Swage, 2000). The key features of clinical governance (Scally & Donaldson 1998) are:

• clear lines of responsibility and accountability for quality

• programme of quality improvement activities

• clear risk reduction policies

• procedures for identifying and addressing poor performance

• public and user involvement.

Figure 16.4 is a mind map of the key activities associated with clinical governance.

Activity

Activity

Activity

ActivityPut yourself at the centre of a mind map like the one in Figure 16.4 and then identify how you can contribute to the clinical governance agenda. You might want to include things like:

• clinical supervision

• reflection

• education and training

• involvement in ward meetings.

|

| Fig. 16.4 Mind map of the key activities associated with clinical governance. |

In July 2004 the Department of Health issued ‘Health and Social Care Standards and Planning Framework 2005/06–2007/08’. This document outlined priorities for the NHS as follows:

Two other major changes were announced in this document:

• Standards for Better Health (DoH 2004). This documented a move away from targets, such as waiting times for operations, to a number of high quality national standards which all hospitals and other health care providers will have to meet. This set out the framework for all NHS organisations and social service authorities to use in planning over the next 3 financial years

• Payment by Results. This is a scheme that provides a national tariff of fees that hospitals may charge for specific interventions, so there is a standard set price for e.g. consultation with a neurologist. In theory, therefore, patients may have more choice about where to access treatment as the money travels with the patient, rather than doctors setting up a contract with a specific hospital.

High Quality Care for All – the Lord Darzi final review

Lord Darzi’s final review, ‘High Quality Care for All’, was published in June 2008. It was highly relevant to planners and commissioners across health and social economies and those providers forging closer partnerships so as to deliver care closer to home. The review concludes a series of reports, consultations and recommendations for a 10-year vision for a world class NHS that is fair, personal, effective and safe. It was based on extensive consultation with 60,000 staff, patients and stakeholder groups (including 2000 clinicians).

An overarching outcome from the review was the focus on bringing about change at the local level, based on sound evidence and in partnership with patients and staff. The vision is that there is ‘an NHS that gives patients and the public more information and choice, works in partnership and has quality of care at its heart. Quality is defined as ‘clinically effective, personal and safe’. The first major priority identified is to tackle the ‘significant variations’ in the quality of care provided across the country. However, it is acknowledged within the review that local flexibility to respond to specific contexts was important, with statements such as: ‘The NHS should be universal, but that does not mean that it should be uniform.’

User involvement

The involvement of service users is an important tenet to the implementation of clinical governance. This presents a challenge to those who are involved in the provision of health care services to children. Although children can be reliable informants who are able to accurately reflect their own lived experiences of being a patient in hospital, it is often assumed that they are not competent to offer a legitimate viewpoint on their experience of health care services (Glasper, 2004 and Woodfield, 2001).

Since the publication of the Bristol Inquiry and the Children’s National Service Framework, government recommendations have been quite strident in their call for greater patient and public involvement. The Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health (PPI) is tasked with giving the public a voice in decisions that affect their health and is operationalised through the Patient Advisory Liaison Service (PALS) at individual Trust level. Importantly, an innovative audit tool is being developed for CHAI to access Trusts against the Children’s NSF based on a model already in use by Essence of care (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003), which will allow individual organisations to benchmark themselves against the NSF standards. It is hoped that this will help to raise the voice of children and truly involve them in their own health care services.

The Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health (CPPIH) was established in January 2003 to set up and support Patients’ Forums. This independent, non-departmental public body (NDPB) was abolished on the 31 March 2008 when Patients’ Forums were replaced by Local Involvement Networks (LINks).

LINks aim to give citizens a stronger voice in how their health and social care services are delivered. Run by local individuals and groups and independently supported – the role of LINks is to find out what people want, monitor local services and to use their powers to hold them to account. Sometimes the people who use services don’t feel they have a strong enough voice to change aspects of their health or social care. The introduction of LINks is part of a wider process to help the community have a stronger local voice. A LINks role once it is up and running is to:

• ask local people what they think about local health care services and provide a chance to suggest ideas to help improve services.

• investigate specific issues of concern to the community.

• use its powers to hold services to account and get results.

• ask for information and get an answer in a specified amount of time.

• be able to carry out spot-checks to see if services are working well (carried out under safeguards).

• make reports and recommendations and receive a response.

• refer issues to the local ‘Overview and Scrutiny Committee’.

Picker Institute Europe works with patients, professionals and policy makers to promote understanding of the patient’s perspective at all levels of health care policy and practice. Their results form part of the core quality standards set out by the Care quality commission (www.cqc.org.uk). Their national surveys help them find out about patients’ and service users’ experiences of health care.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access