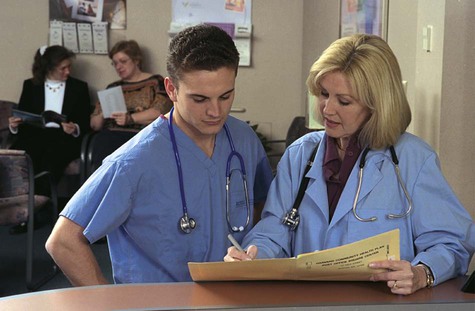

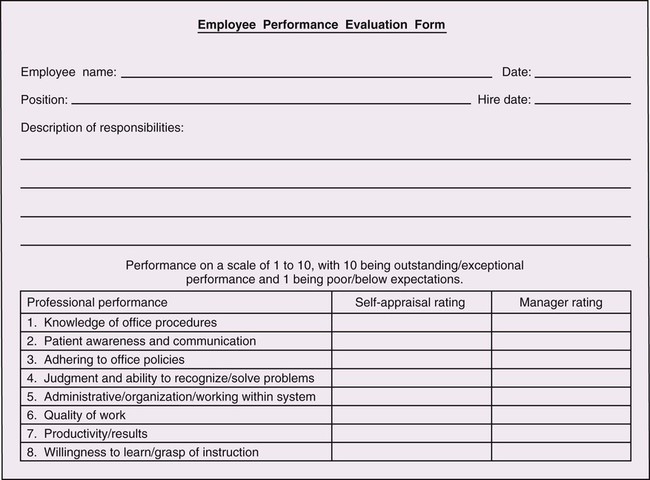

Chapter 9 Review Box 9-1 for the six steps of critical thinking. Reflect on these steps as you read this section. Employee A: “We have a big problem.” Employee B: “I think I see a way we can avoid facing a big mess next month.” * Bring the problem to your manager’s attention as soon as you become aware of it. Many problems can be easily dealt with early but become difficult if action is delayed. * Gather as many facts about the problem as you can. If you are unclear on the facts, investigate their accuracy before you inform your supervisor. Revising the facts later can be difficult and damaging when a solution built on false information has to be reversed. Your manager is there to offer you training, guidance, feedback, criticism, and encouragement. Rather than waiting for your manager to bestow these blessings on you, it will be easier for your manager if you seek them out, to help guide you in making better decisions, getting more work done, and achieving the mission of your employer. In Figure 9-1, a health professional seeks guidance from his supervisor. To help establish rapport with your boss, mirror her body language, as you learned in Chapter 7. Proper body language helps people bond and treat each other as professionals engaged in a business discussion. Smile if it is appropriate. Make small talk at the beginning, but keep it short. Get to the point, and state the purpose of your conversation clearly. As in all conversations, practice active listening skills, as you learned in Chapter 7. The more your manager talks, the more you will learn, and the better the questions you can ask. Be appreciative of your manager’s time, but be sure you clearly understand any directions you receive or promises you make. Ask questions to be sure you understand. If necessary, summarize your understanding verbally or in a follow-up email. Always inform your supervisor of actions you took in response to your conversation. Clarity and follow-up are two qualities all managers prize in their employees. Box 9-2 reviews some of the most common mistakes people make when communicating with supervisors. Brace yourself. How would you react if your supervisor said one of the following statements to you: * “I know you don’t mean it to be, but it feels disrespectful to those who are speaking when you tap on the table during our meetings.” * “Do you realize that sometimes you cut patients off during intake interviews?” At regular intervals, usually annually (and sometimes more often if you’re a new employee), you can expect to receive a formal performance evaluation from your supervisor. This evaluation covers the entire period since the last evaluation, and it becomes part of your file in Human Resources. Sometimes the performance evaluation is used to determine pay raises. Regardless of whatever salary implications it may or may not carry, the performance evaluation is a major opportunity for you and your supervisor to agree on your strengths and weaknesses and decide what developmental and learning goals you will work on in the coming review period. Of course, this periodic evaluation is not the only time you should solicit feedback from your boss. Between reviews, refer to your practice’s performance evaluation form as a reminder of growth opportunities. See Figure 9-2 for a sample evaluation. * What is driving my boss’s behavior? Why is she acting like that? * Is this a temporary behavior, or a personality problem? * Am I a target, or is everyone treated this way? * Am I doing anything to contribute to my boss’s bad behavior? * Based on what I know about my boss, is there anything I can do to improve the situation?

Enhancing Your Promotability

Learn how to form a positive relationship with your manager.

Learn how to form a positive relationship with your manager.

Develop strategies for handling difficult conversations with your manager.

Develop strategies for handling difficult conversations with your manager.

Understand the benefits of taking a accountability for your actions.

Understand the benefits of taking a accountability for your actions.

Identify what teams you belong to.

Identify what teams you belong to.

List ways you can maximize your role on your teams.

List ways you can maximize your role on your teams.

Explain the benefits of joining a professional organization.

Explain the benefits of joining a professional organization.

Thinking Critically

Learning Objectives for Thinking Critically

Recognize the value of critical thinking and how it can advance your career.

Recognize the value of critical thinking and how it can advance your career.

Challenge yourself to gather in-depth information and learn as much as possible about your profession.

Challenge yourself to gather in-depth information and learn as much as possible about your profession.

Train yourself to observe critically.

Train yourself to observe critically.

Develop focus, objectivity, inference, and selectiveness when approaching all situations.

Develop focus, objectivity, inference, and selectiveness when approaching all situations.

Identify the problem, issue, concern, or question being discussed or considered in any given situation.

Identify the problem, issue, concern, or question being discussed or considered in any given situation.

Understand why you are thinking about the problem; what accomplishment will it help you with? In healthcare, this answer involves knowing what to believe or do in many situations.

Understand why you are thinking about the problem; what accomplishment will it help you with? In healthcare, this answer involves knowing what to believe or do in many situations.

Take notice of your own ideas about an issue, and how they change your thinking compared to another person’s view. Strive to be fair-minded.

Take notice of your own ideas about an issue, and how they change your thinking compared to another person’s view. Strive to be fair-minded.

Become a problem solver using the steps to critical thinking.

Become a problem solver using the steps to critical thinking.

Talking to Your Manager or Supervisor

Learning Objectives for Talking to Your Manager or Supervisor

Have a strategy for developing a positive relationship with your boss.

Have a strategy for developing a positive relationship with your boss.

Handle difficult conversations with your manager.

Handle difficult conversations with your manager.

Develop solutions to problems.

Develop solutions to problems.

Use your supervisor as an advisor and source of feedback.

Use your supervisor as an advisor and source of feedback.

Manage the performance evaluation process.

Manage the performance evaluation process.

Managing Up

Bring Solutions to Your Supervisor

Seek Your Manager’s Guidance

Conversations with Your Boss

Seek Feedback and Even Criticism from Your Supervisor

Your Performance Evaluation

What if You Have a Difficult Boss?

Approaches to Dealing with Your Manager’s Difficult Behavior

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Enhancing Your Promotability

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access