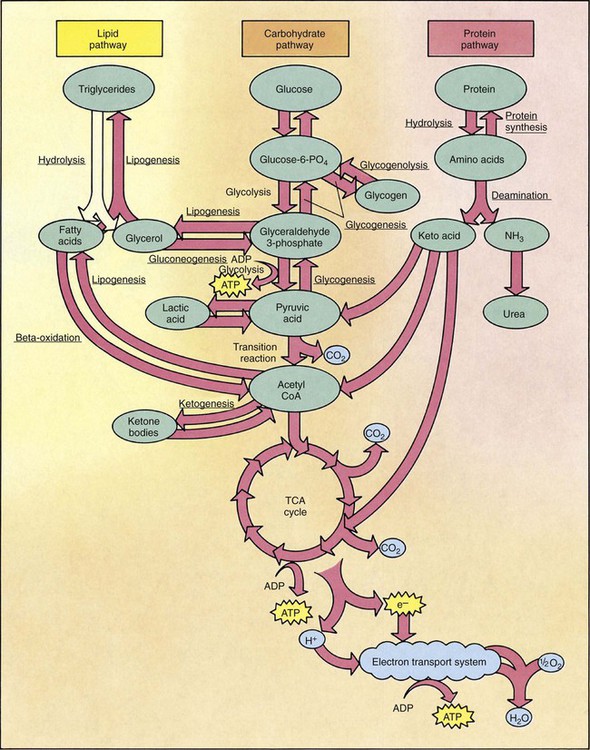

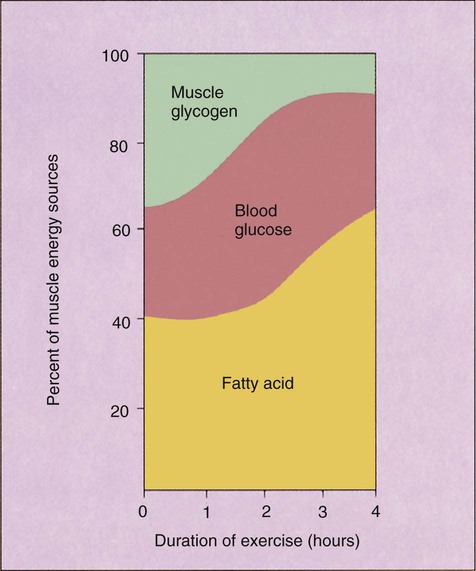

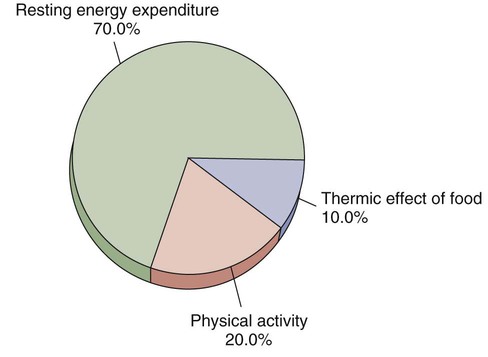

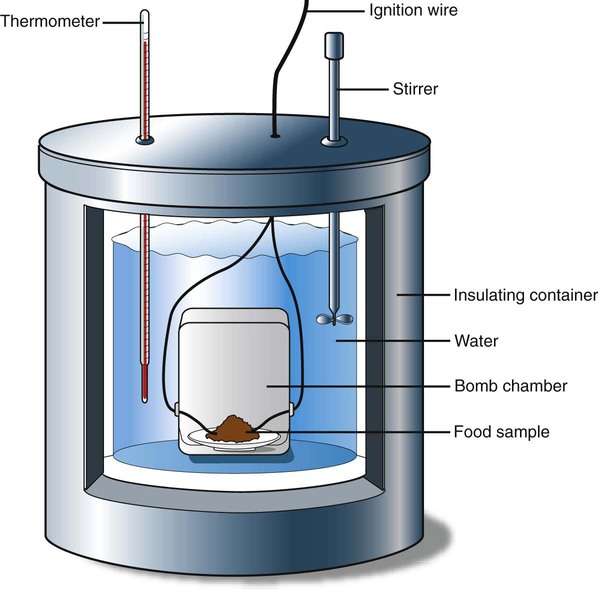

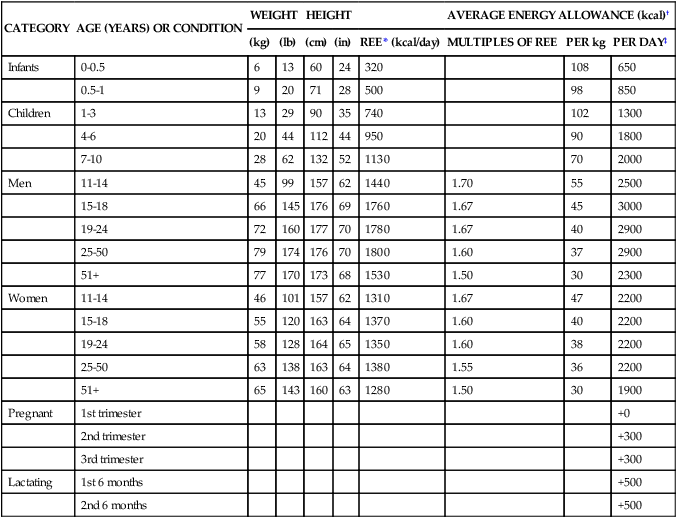

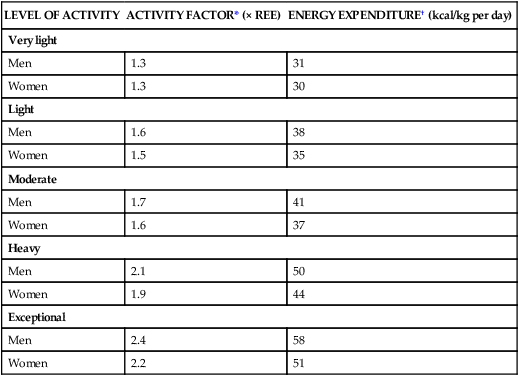

Physical activity has always been recognized as a component of health. Within the past decade this importance has increased because an inverse relationship between level of fitness and risk of development of chronic degenerative disorders is becoming better understood. This means that the less physical activity a person experiences, the greater the risk of developing disorders such as diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), cancer, and hypertension. This chapter addresses the health benefits of exercise as complementing optimum nutrition to decrease risk factors and as improving quality of life. In the nursing profession, we may also work with athletes of all ages who will benefit from our knowledge of their physical requirements. Consequently, this chapter discusses specific nutrient issues that affect the athlete, defined as “a person who is trained or skilled in exercises, sports, or games requiring physical strength, agility, or stamina.”1 Finally, as nurses we have a responsibility to maintain our own fitness levels as role models for our clients and for our own benefits to function comfortably in our sometimes physically demanding profession. The energy released from food is measured in kcal (thousands of calories), or Calories. Technically, a calorie is the amount of heat necessary to raise the temperature of a gram of water by 1° C (0.8° F). As first noted in Chapter 1, to ensure accuracy, the term kilocalories is used throughout this text, abbreviated as kcal. Two methods are used to determine the energy a food contains. One is through the use of a bomb calorimeter (Figure 9-1). This instrument is designed to burn a food while measuring the amount of heat or energy released. This provides an estimate of the energy available to humans. Because the bomb calorimeter method is more efficient than the human body, the kcal value assigned to a food item is adjusted to reflect the limitations of the human system. Amounts listed in food tables reflect this adjustment. Amino acids are first catabolized through deamination, as described in Chapter 6. Whereas the liver and kidneys process the nitrogen-containing amino acid groups, the other amino acid components enter the energy metabolism pathway, with each component entering at a different location. Some of the amino acid components are converted to pyruvic acid; others become intermediaries of the TCA cycle or part of the acetyl groups. If sufficient energy is available, amino acids are used for protein synthesis rather than for energy. It is important to note that just as all three nutrients (carbohydrate, protein, and fat) can be used for energy when consumed in excess, they can also be stored as fat in the body. Likewise, when too little energy is consumed, these processes reverse. Energy that is consumed is used immediately, regardless of its source. The first stored energy used is glycogen, followed by the energy reserve of body fat in adipose cells. Glucose must be available to the brain. Only a small portion of triglycerides (glycerol) can yield glucose, and continuous use of this source results in a buildup of ketones and the potential imbalance of the body pH (see Chapter 6). The body prefers to spare protein for its more important function: building and repairing cells and tissues. The length of activity also determines what type of fuel the muscles will use during exercise. As the duration of exercise increases, glycogen stores become depleted and fat becomes the primary source of energy (Figure 9-3). A sedentary person breaks down glycogen faster and as a result accumulates more lactic acid in the tissues. The lactic acid causes muscle fatigue. A physically fit person has a higher aerobic capacity (the ability of the heart to supply oxygen) so that oxygen is available sooner and in greater quantity; this allows use of the aerobic pathway of energy, avoiding lactic acid buildup. This also means that more fat than glycogen can be used for fuel. The recommended energy allowances published by the National Research Council appear in Table 9-1. These energy values are based on individuals with a light to moderate activity level. The average daily energy intake for the referenced 19- to 24-year-old man is 2900 kcal, or 40 kcal/kg. It is 2200 kcal or 38 kcal/kg for the same age-referenced woman. If a person is more active or of a larger or smaller body size, further adjustments must be made. Most important, these levels are simply guidelines; the only accurate recommendation for individuals is one that supports healthy weight levels. TABLE 9-1 MEDIAN HEIGHTS AND WEIGHTS AND RECOMMENDED ENERGY INTAKE *REE, Resting energy expenditure; calculation based on Food and Agriculture Organizations (FAO) equations, then rounded. †In the range of light to moderate activity, the coefficient of variation is ± 20%. From National Academies of Sciences, Food and Nutrition Board, National Research Council: Recommended dietary allowances, ed 10, Washington, DC, 1989, National Academies Press. Many different formulas have been developed to estimate energy expenditure, some of which are complicated. An easy way to determine kcal need is to multiply weight by one of the numbers in Table 9-2. For example, a 77-kg (170-pound) man who participates in moderate exercise needs about 3060 kcal a day. Remember that these numbers represent averages. Some people need fewer kcal; others need more. TABLE 9-2 *Based on examples presented by World Health Organization (1985). †Resting energy expenditure (REE) is the average of values for median weights of people ages 19 to 24 and 25 to 74 years: men, 24 kcal/kg; women, 23.2 kcal/kg. Many scientists, however, prefer to use a more practical measurement called resting energy expenditure (REE). REE is the energy a person expends in a normal life situation while at rest, and it includes some energy the body uses following meals and exercise. It accounts for approximately 60% to 75% of our total energy needs, similar percentages to those of BMR (Figure 9-4). Body size affects energy expenditure more than any other single factor. A heavier person uses more energy to perform a given task than does a lighter person. Table 9-3 shows the number of kcal burned per hour for two individuals, one weighing 205 pounds and the other 125 pounds, as they engage in various activities. TABLE 9-3 APPROXIMATE CALORIES USED PER HOUR

Energy Supply and Fitness

Role in Wellness

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grodner/foundations/ ![]() Nutrition Concepts Online

Nutrition Concepts Online

Energy

Protein as a Source of Energy

Anaerobic and Aerobic Pathways

Energy Balance

Estimating Daily Energy Needs

CATEGORY

AGE (YEARS) OR CONDITION

WEIGHT

HEIGHT

AVERAGE ENERGY ALLOWANCE (kcal)†

(kg)

(lb)

(cm)

(in)

REE* (kcal/day)

MULTIPLES OF REE

PER kg

PER DAY‡

Infants

0-0.5

6

13

60

24

320

108

650

0.5-1

9

20

71

28

500

98

850

Children

1-3

13

29

90

35

740

102

1300

4-6

20

44

112

44

950

90

1800

7-10

28

62

132

52

1130

70

2000

Men

11-14

45

99

157

62

1440

1.70

55

2500

15-18

66

145

176

69

1760

1.67

45

3000

19-24

72

160

177

70

1780

1.67

40

2900

25-50

79

174

176

70

1800

1.60

37

2900

51+

77

170

173

68

1530

1.50

30

2300

Women

11-14

46

101

157

62

1310

1.67

47

2200

15-18

55

120

163

64

1370

1.60

40

2200

19-24

58

128

164

65

1350

1.60

38

2200

25-50

63

138

163

64

1380

1.55

36

2200

51+

65

143

160

63

1280

1.50

30

1900

Pregnant

1st trimester

+0

2nd trimester

+300

3rd trimester

+300

Lactating

1st 6 months

+500

2nd 6 months

+500

LEVEL OF ACTIVITY

ACTIVITY FACTOR* (× REE)

ENERGY EXPENDITURE† (kcal/kg per day)

Very light

Men

1.3

31

Women

1.3

30

Light

Men

1.6

38

Women

1.5

35

Moderate

Men

1.7

41

Women

1.6

37

Heavy

Men

2.1

50

Women

1.9

44

Exceptional

Men

2.4

58

Women

2.2

51

Components of Total Energy Expenditure

Physical Activity

125-lb PERSON

ACTIVITY

205-lb PERSON

234

Baseball—infield or outfield

382

299

—pitching

488

352

Basketball—moderate

575

495

—vigorous

807

251

Bicycling—on level ground, 5.5 mph

409

537

13 mph

877

209

Dancing—moderate

341

284

—vigorous

464

416

Football

678

271

Golf—twosome

443

165

Horseback riding—walk

270

338

—trot

551

503

Mountain climbing

820

251

Rowing—pleasure

409

684

—rowing machine or sculling 20 strokes/min

1116

537

Running—5.5 mph

887

669

—7 mph

1141

777

—9 mph level

1269

285

Skating—moderate

465

513

—vigorous

837

483

Skiing—downhill

789

586

—level, 5 mph

956

447

Soccer

730

194

Swimming—backstroke—20 yd/min

316

418

—40 yd/min

682

241

—breaststroke—20 yd/min

392

482

—40 yd/min

786

586

—butterfly

956

241

—crawl—20 yd/min

392

532

—50 yd/min

869

347

Tennis—moderate

565

488

—vigorous

797

285

Volleyball—moderate

565

488

—vigorous

797

176

Walking—2 mph

286

331

—4.5 mph

540

643

Wrestling, judo, or karate

1049 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree