CHAPTER 6 End-of-Life Issues in the Emergency Department

I. OVERVIEW

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 317,000 persons died in emergency departments in the United States in 2003.1 Because the emergency department is a fast-paced and frequently high-stress, high-anxiety department, end-of-life issues are often given a lower priority. Clinical personnel may make decisions regarding patient care with suboptimal levels of information.2–4 Relationships among personnel, patients, and families are limited during a time of crisis.5,6 Additionally, the emergency department is usually a place of transition where patients receive stabilizing treatment and then are either transferred out or discharged. Patients usually do not remain in the emergency department for the duration of their hospital stay.7

The United States is a rescue-oriented culture.7 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and other advanced life support measures are routinely employed in end-of-life scenarios. However, some patients do not require or want basic or advanced life support measures performed, and they may request only care-and-comfort measures at the end of their life.7 It is important to recognize that some patients have a poor prognosis, and although staff members have many interventions available (e.g., intubation equipment, chest compressions), these interventions are not appropriate for all patients at or near the end of life. Careful exploration with patients and families regarding their life goals and expectations for care can help determine what interventions are appropriate.8 For example, patients in severe respiratory distress may be brought to the emergency department by ambulance not necessarily for mechanical ventilation but because it became frightening for the family to have the patient die at home.

The interval referred to as the “end of life” is not well defined and is used inconsistently,9 but the term frequently applies to any interval when a patient is approaching the finality of cardiopulmonary or brain death. Emergency department staff members have a pivotal role in providing care that may be most beneficial to the patient and family. Planning that care requires engagement with the patient and family in order to explore goals and to determine which interventions are and are not appropriate. It is also important to determine, from the patient if possible, who should receive information and who should be allowed in the treatment area at this end stage.10

Emergency nurses encounter death frequently in their clinical practice, and caring for dying patients may become routine,11 sometimes leading nurses to become desensitized to the suffering around them.6 Conversely, patients and families are often unfamiliar with death and dying. They come to the emergency department with unexpected injuries or illnesses, with chronic disease exacerbations, or with terminal illnesses seeking symptom management and lifesaving or life-prolonging treatment.7 Patients and families are often in crisis and seek help and answers from emergency personnel.6

There are seven trajectories of approaching death in the emergency department: (1) dead on arrival; (2) resuscitation in the field, resuscitative efforts in the emergency department, died in the emergency department; (3) resuscitation in the field, resuscitative efforts in the emergency department, resuscitated, and admitted to the hospital; (4) terminally ill, coming to the emergency department; (5) frail, hovering near death; (6) arriving at the emergency department alive and then suffering cardiac arrest or sudden death in the emergency department; and (7) potentially preventable death by acts of omission or commission.12 Although emergency health care providers are masters at resuscitation, there are dying trajectories that require care interventions other than resuscitative measures. Some dying trajectories benefit from aggressive symptom management and humanistic care, whereas others call for more aggressive interventions.

Recognition of poor prognoses and framing beneficial interventions with the patient and family will help determine the plan of care. Although resuscitative measures are the standard of care in the emergency department, they may not be appropriate for all patients near the end of life. Fear of liability may be a concern of emergency personnel.7,8 However, expanding the definition of “success” from the traditional concept of resuscitation to include aggressive palliative care management can ease emergency personnel’s feelings of abandoning the patient.8

II. PALLIATIVE CARE SYMPTOM MANAGEMENT

Palliative care is patient and family centered and multidisciplinary, and it includes symptom management, emotional/psychological care, social care, spiritual/existential care, advanced care planning, and bereavement care for the survivors.13–15 In end-stage disease, treatment to relieve symptoms may be more appropriate than treatment of the underlying cause, such as infection or tumor progression. The patient must be assessed and reassessed for the presence, improvement, or reduction of symptoms before and after any intervention. Many interventions may be seen as palliative as well as therapeutic.

In patients who are near the end of life, careful consideration should be made when ordering diagnostic tests. Each test ordered should help determine an intervention. However, if the results will not change the management of the patient’s condition, the test should be questioned for its appropriateness.16

A. Advanced Preparation before Deciding on a Plan of Care17

1. Identify the diagnosis and the prognosis

2. Determine what the patient or surrogate already knows

3. Ask whether the patient has an advance directive. If it is not readily available, ask the surrogate decision-maker what the advance directive states, and request a written copy

as soon as possible. Document in the medical record what the surrogate decision-maker states is in the advance directive

4. Seek assistance from other members of the health care team (e.g., social worker, chaplain, patient care advocate) or ask the patient or family whether they want help in contacting someone to be with them in the emergency department

5. Establish a therapeutic milieu17

6. Seek patient and surrogate knowledge about diagnosis and prognosis17

7. Make a palliative care treatment recommendation17

8. Seek patient or surrogate agreement with recommendations17

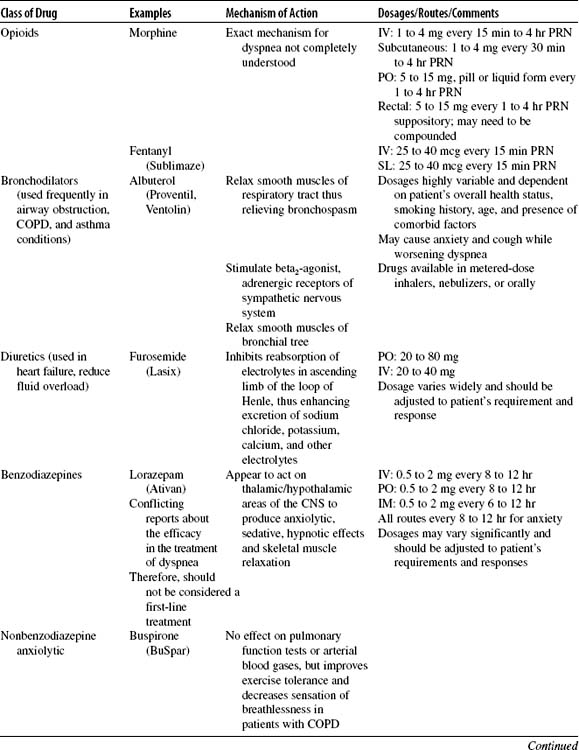

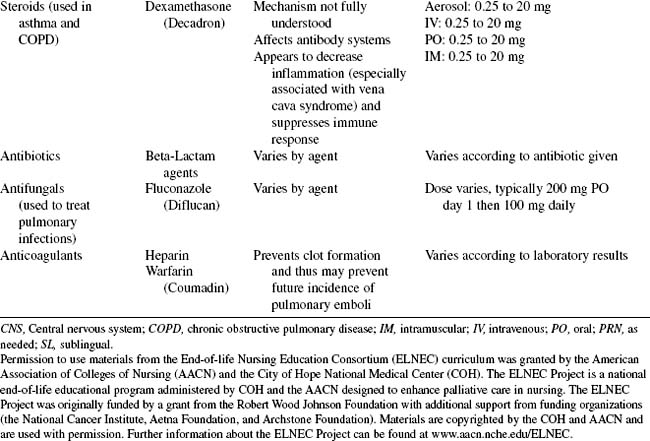

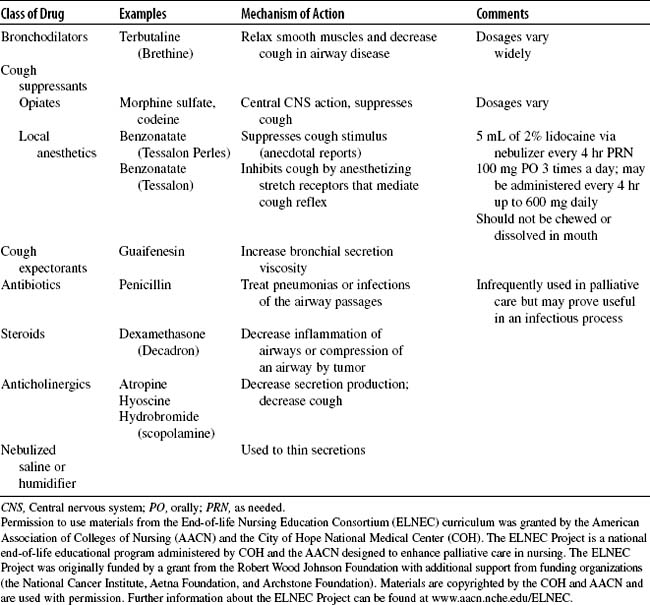

B. Common Symptoms (Table 6-1)

Table 6-1 COMMON SYMPTOMS AT THE END OF LIFE

| Body System | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Pulmonary | |

| Neurologic/functional | |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Urinary | |

| Integumentary | |

| Psychiatric | |

| Other | Fever |

Modified from Ferrell, B. R. (1998). HOPE: Home Care Outreach for Palliative Care Education Project. Duarte, CA: City of Hope.

The incidence of nausea is quite common in advanced disease; it occurs in up to 60% of terminally ill patients.18 Vomiting occurs in approximately 30% of patients, but unfortunately, this symptom has not been well researched in patients with advanced disease. The pathophysiology of nausea and vomiting is extremely complex, requiring careful assessment of the cause, which should lead to an appropriate treatment. Nausea and vomiting can be acute, anticipatory, or delayed.

Diarrhea is the frequent passage of loose, nonformed stool resulting in three or more bowel movements in 1 day.19 Although much less common than constipation in the palliative care setting, diarrhea remains a common symptom. It may be especially problematic in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. It can dramatically affect a person’s quality of life.19 Continuous diarrhea produces fatigue, electrolyte abnormalities, and depression and may cause a person to become homebound. Ongoing diarrhea can exhaust both patients and family. This situation can be embarrassing and time consuming and can lead to problems such as skin breakdown and dehydration.