Mary K. Kazanowski

End-of-Life Care

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

8 Assess patients for signs and symptoms related to the end of life.

9 Explain how to provide evidence-based end-of-life care to the dying patient.

10 Explain best practice guidelines for performing postmortem care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Overview of Death and Dying

Although dying is part of the normal life cycle, it is often feared as a time of pain and suffering. For the family, death of a member is a life-altering loss that can cause significant and prolonged suffering. As sad and difficult as the death may be, the experience of dying need not be physically painful for the patient or emotionally agonizing for the family. The dying process is an opportunity to change a potentially difficult situation into one that is tolerable, peaceful, and meaningful for the patient and the family left behind.

Because nurses spend more time with patients than do any other health care providers, it is the nurse who often has the greatest impact on a person’s experience with death. It is the nurse who can affect the dying process to prevent a death without dignity (“bad” death) from occurring, while striving to promote a peaceful and meaningful death (“good death”). To accomplish this, the nurse needs to have knowledge of end-of-life care, compassion, advocacy, and therapeutic communication skills.

Perception of Death in the United States

The U.S. health care system is based on the acute care model, which is focused on prevention, early detection, and cure of disease. This focus and the advances in survival rates for once deadly diseases have made it difficult for many patients and health care providers to accept death as an outcome of disease. Many view death as a failure.

These negative views have led to a major deficiency in the quality of care provided to many Americans at the end of life. In 1995, a landmark study highlighted the poor quality of dying experienced by hospitalized patients. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment (SUPPORT) showed that more than 50% of a sample of 9105 hospitalized patients with a life-threatening disease had moderate to severe pain during the last days of their lives. In addition, they did not have their wishes met, even when their wishes were known.

As a result of SUPPORT, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) studied death in America. The Institute recommended that a major initiative be undertaken to improve care at the end of life with the outcome of facilitating good death. A good death is one that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers; in agreement with patients’ and families’ wishes; and consistent with clinical practice standards. Pain, not having one’s wishes followed at the end of one’s life, isolation, abandonment, and agonizing about losses associated with death are characteristics of a bad death. In response to this initiative, core curricula on end-of-life care were developed and implemented to educate medical and nursing students, physicians, and nurses on how to provide quality end-of-life care.

Pathophysiology of Dying

Death is defined as the cessation of integrated tissue and organ function, manifested by lack of heartbeat, absence of spontaneous respirations, or irreversible brain dysfunction. It generally occurs as a result of an illness or trauma that overwhelms the compensatory mechanisms of the body, eventually leading to cardiopulmonary failure/arrest. Direct causes of death include:

Inadequate perfusion to body tissues deprives cells of their source of oxygen, which leads to anaerobic metabolism with acidosis, hyperkalemia, and tissue ischemia. Dramatic changes in vital organs lead to the release of toxic metabolites and destructive enzymes, referred to as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). As illness or organ damage progresses, the syndrome occurs with renal and liver failure. Renal or liver failure can also start the dying process.

When the body is hypoxic and acidotic, a lethal dysrhythmia such as ventricular fibrillation or asystole can occur, which ultimately leads to the lack of cardiac output. Shortly after cardiac arrest, respiratory arrest occurs. When respiratory arrest occurs first, cardiac arrest follows within minutes.

Incidence of Death

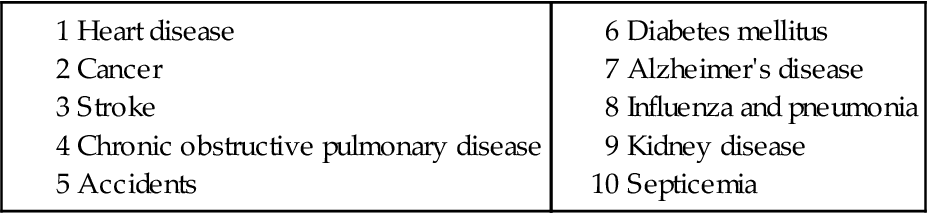

Over 2 million deaths occur every year in the United States. The most common causes of death in the United States are diseases of the heart, followed by cancer (Table 9-1).

Of all people who die, only a few (<10%) die suddenly and unexpectedly. Most people die after a long period of illness (e.g., cardiac, renal, respiratory disease), with gradual deterioration until an active dying phase before the death. Most people who die are older than 65 years.

In general, about 25% of all deaths in the United States take place at home. The rest occur in hospitals or nursing homes, but exact numbers vary depending on the region of the country.

Planning for End-of-Life and Advance Directives

Most people would prefer to die at home. Providing the type of care a person prefers, including where he or she wants end-of-life care, positively affects the dying experience for both the patient and family. These preferences need to be written as legal documents called advance directives.

Most Americans do not have advance directives, and many health care providers do not talk with patients about their wishes for end-of-life (EOL) care until the patients are unable to make their own decisions. Recent data suggest that older adults want early discussions with their health care provider in preparation for death (Gillick, 2010).

The primary purpose of a written advance directive is to provide guidance, especially to health care professionals, regarding how to make decisions regarding life-sustaining treatment when one loses his or her decision-making ability. To have decision-making ability, a person must be able to perform three tasks:

1 Receive information (but not necessarily oriented ×4)

2 Evaluate, deliberate, and mentally manipulate information

By definition, the comatose patient does not have decisional ability. In this case, it becomes unclear as to how health care decisions will be made, who has the authority to make them, and what the treatment should be (Perrin, 2010a).

There are two general types of advance directives. The first is an instructional directive, which states the type and amount of care a person would want if he or she were to become incapacitated. Living wills and medical directives, such as do not resuscitate (DNR) orders, are examples of instructional directives (Perrin, 2010a).

Ethics and DNR Orders

By law, health care providers must initiate cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) for a person who is not breathing or is pulseless unless that person has a DNR order. Although CPR may be effective in patients with reversible illness or single organ dysfunction, patients with terminal cancer, multisystem organ failure, and renal failure rarely survive after a cardiac arrest. Therefore a DNR order may be written in advance (called a portable DNR) before the patient is admitted to a health care facility. For patients who want this type of advance directive, remind them to follow their state’s requirements. Most states that recognize portable DNR directives require that a state-designated, original and signed wallet DNR card (usually pink or bright-colored) be with the patient at all times. Patients may also wear a special DNR bracelet or necklace but must have the signed wallet card with them to ensure that pre-hospital providers follow the advance directive.

Unfortunately, most patients do not obtain a portable DNR. In this case, DNR orders are usually written only a day or two before the patient’s death. In general, physicians do not want to have emotional and time-consuming EOL conversations in advance. However, nurses are willing to discuss DNR options with patients and their families so that they can be involved in their own EOL decisions (Morrell et al., 2008). According to the American Nurses Association Code of Ethics, nurses have an ethical obligation to ensure that the patient, health care proxy, or surrogate has timely information about expected care outcomes to help them make the best possible decisions (Lachman, 2010).

A major problem with DNR orders is their unclear variations, including partial DNR (e.g., cardiac DNR or Do Not Intubate) or “slow code” orders. Several authors have suggested that these orders are medically and ethically inappropriate (Venneman et al., 2008). Instead, plans of care should be established for each person at the end of life.

Another problem with DNR orders is that they can be perceived by families and significant others that they are giving permission to end a patient’s life. Some experts in death and dying have suggested that the term “allowing natural death” (AND) replace DNR. This newer term better describes a clearer intent and is less emotional and threatening than DNR (Venneman et al., 2008).

Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care

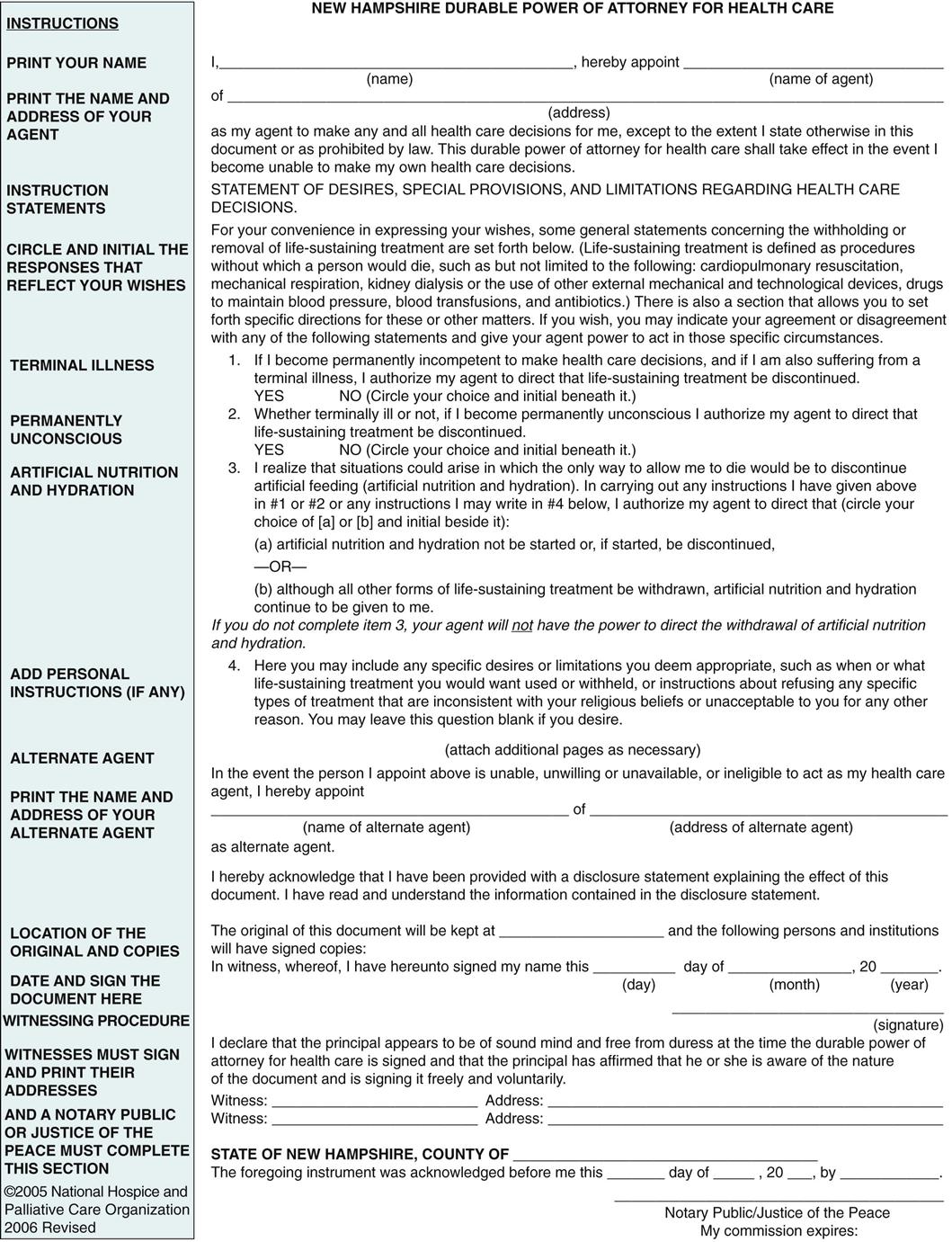

The second type of advance directive is the durable power of attorney for health care (DPOAHC). The DPOAHC is a legal document in which a person appoints someone else (e.g., health care proxy) to make his or her health care decisions in the event he or she loses decision-making capacity (Fig. 9-1).

Advance directives vary from state to state but are readily available through Caring Connections, an online program of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (2005) (www.caringinfo.org). Anyone can complete the advance directive forms without legal consultation. A copy of each directive should be given to the primary health care provider and health care proxy. Remind the patients and health care proxy to keep the advance directive(s) in a secure place, such as a safe deposit box or fireproof box. Remind patients that they can change their mind at any time of their lives or at end of life.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 requires that all patients admitted to health care agencies be asked if they have written advance directives (ADs). Patients who do not have them are provided with information on the value of having an AD in place, are advised on how they might want to choose as their DPOAHC, and are given the opportunity to complete the state-required forms. Ideally, they should be completed long before a medical crisis. Be sure to find out if your patients have these documents to ensure that the health care team follows each patient’s preferences at the end of life. Because of conflict of interest, direct caregivers, such as nurses and physicians, should not witness the signature of any patient who signs advance directives.

Desired Outcomes for End-of-Life Care

The desired outcomes for a patient near the end of life (EOL) are that the patient will have:

Interventions are planned to meet the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients using an interdisciplinary approach. The coordinated, interdisciplinary care of hospice is the most successful approach to end-of-life care to date. Although the perception of hospice is that it provides care for the dying, the major focus of hospice care is on quality of life.

Hospice and Palliative Care

The concept of hospice in the United States resulted from a grassroots effort in response to the unmet needs of terminally ill people. As both a philosophy and a system of care, hospice care uses an interdisciplinary approach to assess and address the holistic needs of patients and families to facilitate quality of life and a peaceful death (Taylor, 2009). This holistic approach neither hastens nor postpones death but provides relief of symptoms. Hospice systems of care are provided in a variety of settings. They are often affiliated with home care agencies, providing services to patients at home or in a long-term care or assisted-living facility. Some communities also have hospice houses, which provide care to patients in the terminal phase of their lives.

The Medicare Hospice Benefits serves as a guide for hospice care in the United States. These benefits pay for hospice services for Medicare recipients who have a prognosis of 6 months or less to live and who agree to forgo curative treatment for their terminal illness. Historically, those with terminal cancer have received hospice care more than other groups.

Guidelines are available to assist health care providers and families in identifying who is entitled to hospice care under Medicare. Patients who do not qualify for Medicare may have benefits through private insurance or government programs like medical assistance programs (e.g., Medicaid).

Because hospice benefits and care generally require a prognosis of 6 months or less, its use is limited. Many people with chronic, serious illness whose prognosis may be longer than 6 months often do not have access to the support services that work so well within the hospice model. In an attempt to address this need, palliative care has evolved.

Palliative care is both a philosophy of care and an organized, structured system for delivering care for people with serious illness who may not meet hospice eligibility criteria. The desired outcome for palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering and to support the best possible quality of life for patients and their families, regardless of the stage of the disease or the need for other therapies. For older adults, palliation also includes enhancing or supporting functional independence as they transition between levels of care.

Signs and Symptoms at End of Life

Overview

As death nears, patients often have signs and symptoms of decline in physical function, manifested as weakness, anorexia, and changes in cardiovascular function, breathing patterns, and GI and genitourinary function. As death nears, peripheral circulation decreases and the patient’s skin is often cold, mottled, and cyanotic. Blood pressure decreases and often is only palpable. The dying person’s heart rate may increase, become irregular, gradually decrease, and stop. Changes in breathing pattern are common, with breaths becoming very shallow and rapid. Periods of apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations (apnea alternating with periods of rapid breathing) are also common. Death occurs when respirations and heartbeat stop.

Although these signs and symptoms of physical decline are often disturbing to patients and families, they generally do not cause physical discomfort to the patient. However, symptoms of distress that cause suffering can occur in patients with cancer and non-cancer diagnoses. Pain, weakness, and breathlessness are the most common symptoms near end of life.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Obtain information about the patient’s diagnosis, past medical history, and recent state of health to identify the risks for symptoms of distress at end of life. For example, people with lung cancer, heart failure, or chronic respiratory disease are at high risk for respiratory distress and dyspnea near death. Those with brain tumors are at risk for seizure activity. Patients with tumors near major arteries (e.g., head and neck cancer) are at risk for hemorrhage. Those who have been experiencing pain often continue to have pain at the end of life, which may increase, decrease, or remain at the same level of intensity.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Near the end of life, the patient often becomes weak and drowsy, often sleeping 23 or more hours of the day. Eventually he or she can become unresponsive. As the patient’s ability to speak diminishes, it is difficult to assess his or her perception of symptoms. When caring for those who are unable to communicate their distress or needs, identify alternative ways to assess symptoms of distress. Teach family caregivers to watch closely for objective signs of discomfort (e.g., restlessness, grimacing, moaning) and identify when these symptoms occur in relation to positioning, movement, medication, or other external stimuli (Chart 9-1).