Chapter 14. Enabling healthier living

Chapter Contents

Models of behaviour change192

Working with a client’s motivation195

Working for client self-empowerment195

Strategies for increasing self-awareness, clarifying values and changing attitudes196

Strategies for decision making198

Strategies for changing behaviour199

Using strategies effectively201

Summary

This chapter considers the approaches used to support people in making changes to their health-related behaviour. In the first section there is an overview of two behaviour change models. This is followed by a section on working with a client’s motivation and how to work towards client self-empowerment, strategies for increasing self-awareness, clarifying values and changing attitudes. Strategies for decision making and for changing behaviour follow. The chapter ends with principles for using behaviour change approaches effectively and summarises key points. It includes exercises, examples and a case study.

This chapter focuses on the competencies you need when you are enabling people to make changes to their health-related behaviour and lifestyles. Health behaviour may have developed without conscious decision making and in response to individual and group circumstances and external events. Active control of behaviour is different because it involves committing time and effort (yours and your client’s) to understanding the factors that influence health choices and behaviour, and to taking considered decisions and actions.

However, it has to be accepted that people may prefer to carry on with behaviour that seems unhealthy to you. To a client, it may not seem unhealthy as the benefits outweigh the risks. Respect for people’s values, opinions and their right to choose are fundamental to establishing relationships between health promoters and their clients.

See Chapter 10, section on exploring relationships with clients.

On the other hand, you also have to consider that a person’s right to individual freedom of choice has to be balanced against the effect of that choice on other people; for example, a parent choosing to smoke could affect their children’s health by subjecting them to passive, secondary smoking.

Furthermore, choosing a healthy behaviour does not automatically lead to practising it. Changes such as taking more exercise, practising relaxation, wearing ear protectors in noisy surroundings, eating healthier foods and stopping smoking can require self-discipline and overcoming barriers which make these changes stressful. Social or economic circumstances can be a significant obstacle to people carrying out new health behaviours, even if they would like to (Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology 2007).

However, despite these limitations, it can be very rewarding to enable people to look at their motivations, beliefs, values and attitudes, and to make and carry out decisions that will lead to improved health and wellbeing (Box 14.1).

BOX 14.1

Counselling about a health choice

A health visitor has the task of helping parents to decide what to do about having their baby vaccinated. The stages could be:

Stages 1 and 2. Identify and explore the need

For example, are the parents worried about having the child vaccinated at all, or is it just the whooping cough vaccination which is worrying? Is it when to have the child vaccinated, or if?

Stage 3. Help the client to set goals and establish options

For example, the parents may identify the goal of the child having the best possible chance of staying healthy.

The options might be: no vaccinations at all, some vaccinations or all the vaccinations.

Stage 4. Help the client to decide which option to choose

▪ Weigh up the pros and cons. The health visitor provides unbiased information on the risks from catching each disease compared with the risks of having the vaccinations.

▪ Consider the likely consequences of pursuing each alternative: for the child in terms of health risk, for the parents, in terms of anxiety, guilt and responsibility, for other people in terms of spreading the diseases.

Stage 5. Help the client to develop an action plan

For example, the parents may decide to go ahead with the vaccination programme, but also to join a parents group, in order to get support from other parents facing the same anxieties and decisions. The health visitor suggests to the parents that they keep a record of the vaccinations for future reference, and provides them with a record card for their child. They set a date for the first vaccination.

Models of Behaviour Change

Health-related behaviour change is a very complex process involving a web of psychological, social and environmental factors. Using behaviour change models will help you to clarify your thinking and make your practice more effective. Models are simplified ways of describing reality and provide frameworks and routes to help you know where to start and what to do. Two models that can be used by health promoters are the Health Action Model and the Stages of Change Model.

The Health Action Model

The Health Action Model (HAM) was devised by Tones (1987 and Tones & Tilford 2001) and emphasises the important influence of self-esteem on behaviour. It assumes that someone with high self-esteem and a positive self-concept is likely to be more motivated towards ways of healthier living and that people with low self-esteem may feel that they have limited control over their behaviour and that they are victims of bad luck or fate. Many health promoters, particularly those working in the field of drugs, have used this model, through concentrating on boosting people’s self-esteem and their skills in resisting peer group pressure. According to this model, learning life skills such as how to be assertive may be essential before someone is ready to change their lifestyle.

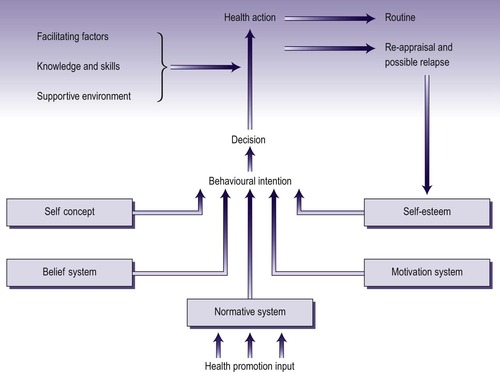

The HAM identifies a variety of psychological, social and environmental influences which research and practice have shown to be important determinants of a number of health choices. The model offers an explanation about how these influences work. It suggests that health decisions and actions are influenced by our beliefs, our values, our motivation, our expectations of how other people will react to our actions and our self-concept and self-esteem (see Fig. 14.1).

|

| Fig. 14.1 The Health Action Model. (Source:Tones 1995. Reproduced with permission from the Health Education Authority). |

The HAM is concerned with empowerment, with increasing the control people have over their lives. It suggests that health promotion should not just focus on the provision of information and the pros and cons of particular behaviours. More important than this are interventions that enable people to value themselves, and to acquire the skills to assert themselves. Equally important is the provision of environmental circumstances that facilitate healthy choices, rather than acting as barriers. And at a broader level, national and local policy needs to address the broader determinants of health, such as poverty and deprivation.

Transtheoretical Model (TTM) and Stages of Change

One way of supporting people in making health-related decisions and changing their behaviour is to consider all the stages in the process, and how people move from one stage to another. The Transtheoretical Model (TTM) developed by Prochaska & DiClemente (1982) is rooted in extensive research and integrates a range of psychological theories. The TTM has evolved over time and now contains five core constructs: stages of change, processes of change, decisional balance, self-efficacy and temptation (Prochaska & Velicer 1997) which provides a valuable conceptual framework for how people naturally change their behaviour. However, there is controversy and debate about whether this can consistently be translated into an intervention programme (see, for example, Aveyard et al 2009 and Prochaska 2009). Studies based on this model, such as Aveyard et al (2006) found no evidence that the smoking cessation intervention based on the model was more effective than a control intervention that was not tailored for stages of change. Armatage (2009) offers a useful critique of the model and an assessment of three studies that deemed to have successfully utilised the processes of change to reduce alcohol consumption, encourage smoking cessation and increase physical activity. It is important before using the approach to be abreast of the controversy and the systematic reviews on it’s effectiveness. A useful summary with a full set of up-to-date references is presented on Wikepedia (http://en.wikipedia.org).

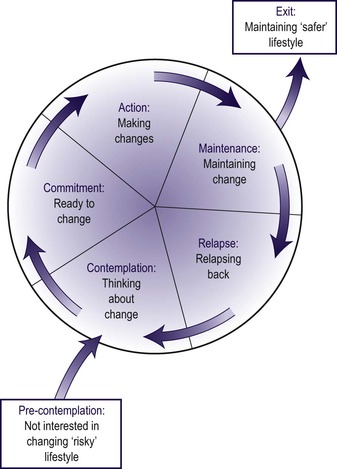

The stages of change component of the TTM identifies a number of stages that a person can go through during the process of behaviour change. It takes a holistic approach, integrating factors such as the role of personal responsibility and choices, and the impact of social and environmental forces that set very real limits on the individual potential for change. It provides a framework for a wide range of potential interventions by health promoters, as well as describing the process individuals go through when acting as their own agents of change; for example, when someone stops smoking without any professional support. The main stages identified in the model are set out in Fig. 14.2 (see also Prochaska 2005).

|

| Fig. 14.2 Stages of changing health behaviour. (Adapted fromProchaska & DiClemente (1984)andNeesham (1993)). |

The key to the model is to regard the cycle in the centre as a series of stages that people go through in the process of changing health behaviour, such as stopping smoking, taking more exercise regularly or adopting healthier eating. A crucial point is that the cycle can be thought of as a revolving door, because people usually go round more than once before emerging to a permanently changed state. It is also important to recognise that some people may never get as far as entering the revolving door.

Pre-contemplation stage

The stage that precedes entry into the change cycle is referred to as pre-contemplation. At this stage a person has no awareness of a need for change, or does not accept it, and has no motivation to change habits or lifestyle.

Contemplation stage

This stage is the way into the revolving door cycle of stages of change. People enter this stage when they have enough motivation to contemplate seriously changing their habits; the entry stage is therefore called contemplation.

Commitment stage

If people continue to progress round the cycle, they enter the commitment stage, in which they make a serious decision to change the particular habit concerned, such as stopping smoking or taking more exercise.

Action stage

They next enter the action stage as they actively begin to change the habit.

Maintenance stage

At this stage people struggle to maintain the change and may experiment with a variety of coping strategies.

Relapse stage

Although individuals experience the satisfaction of a changed lifestyle for varying amounts of time, most of them cannot exit from the revolving door the first time around. Typically, they relapse; for example, they start smoking again. Of great importance, however, is that they do not stop there, but move back into the contemplation stage, engaging in the cycle all over again. Prochaska et al (1992) found that, on average, successful former smokers take three revolutions of change before they find the way to become fully free of the habit, and exit from the revolving door.

Exit stage

This is the stage in which people are settled into a changed behaviour, such as stopping smoking permanently.

By identifying where clients are in the stages of change, health promoters can tailor their interventions to the particular stage. For example, behaviour change strategies are appropriate for someone in the action or maintenance stages; education and awareness raising are appropriate for someone in the pre-contemplation stage; working for client self-empowerment is appropriate for someone in the contemplation stage; strategies to help people to make decisions are useful for those in the commitment stage.

The model can be useful in primary healthcare settings, because clients’ needs can be assessed and appropriate advice or information given, within the constraints of a short consultation.

Working with a Client’s Motivation

Motivation is a state that changes frequently depending on lots of different factors. If people are struggling to maintain their new behaviour, what gets them through this difficult time without relapsing? It is thought that both the importance of the new behaviour (in terms of the expectation of costs and benefits) and the confidence of the person being able to maintain the new behaviour are essential to prevent relapse. The following suggestions can help you explore the importance of the new behaviour with clients, and to build their confidence.

Ideas for exploring importance

• What are the positive aspects of the current behaviour?

• What are the negative aspects of the current behaviour?

• Summarise and ask ‘And is there anything else?’

• Where does that leave you now?

Ideas for building confidence

• Get the client to identify as many solutions as possible which will help to prevent relapse.

• Ask ‘What have you learned from previous attempts to change about what works (or doesn’t work) for you?’

• Ask ‘Are there methods that you know have worked for other people?’

• Aim to help the client develop a clear plan but explain that it can be reviewed at any time.

It is essential to listen actively to the client when exploring readiness to change. Confidence can be divided into self-efficacy and self-esteem. Self-efficacy is concerned with a person’s confidence in being able to make a specific change in behaviour; self-esteem is a more general sense of wellbeing that a person has about themselves. Self-efficacy can vary in different situations, and you can help your clients look at different approaches for improving self-efficacy in situations where they feel less confident.

This section is partly based on Rollnick et al (1999). See also Botelho (2004) and Rollnick et al (2007) for more on motivational practice.

Dangerous Assumptions about Motivation

Health promoters can become very focused on health issues, and may forget that there are other motives for change and that health might not be one of them. The list below illustrates some of the other assumptions that are easy to make when counselling clients.

• This person ought to change.

• This person wants to change.

• It is the right time for this person to change.

• If this person decides not to change, this intervention has failed.

• A tough approach is always best.

• For this person, health is a prime motivator.

• I’m the expert. This person must follow my advice.

Working for Client Self-Empowerment

Making health choices and carrying them out can bring benefits. These are not only the benefits that go with a healthier lifestyle, such as improved health and wellbeing, but also increased self-esteem from the feeling of taking active control over a part of life, such as being in control of the smoking habit rather than cigarettes being in control. In other words, making a positive choice about health can be a self-empowering process.

There are a number of different ways of working towards self-empowerment. Using the Stages of Change is empowering, because people can follow their own progress. It may encourage them to try to get to the next stage of the cycle, and not to see change as all-or-nothing. Also, the recognition that relapse can be part of the process of changing behaviour is important (see Marlatt & Donovan 2007). Behaviour change messages can be tailored to individual need, for example through providing clients with access to specially designed computer programs (Walters et al 2006). Other methods include group work and experiential learning, individual counselling and therapy, and advocacy, all of which are considered in the following sections, except therapy, which is beyond the scope of this book. Unless you are a mental health specialist, most people you work with probably do not need in-depth therapy.

The process of empowerment involves helping clients to become more self-aware, and have greater insight into, and understanding of, themselves, their attitudes, values, motivations and feelings

Strategies for Increasing Self-Awareness, Clarifying Values and Changing Attitudes

Many of the strategies that are useful for increasing self-awareness, clarifying values, developing belief systems and changing attitudes for the contemplation stage of change are designed for group work. However, some of them can be adapted for health promoters to use in one-to-one situations.

See Chapter 13, Working with groups.

All these strategies use the principle of experiential learning, which emphasises the importance of personal experience as a source of learning. Experiential learning has evolved from two sources. One is from the theories of the American philosopher Dewey (1938). Another is from humanistic psychology. Humanistic psychology sees people as free decision makers actively controlling their own destinies. Humanistic psychology has had a huge influence on healthcare, education and health promotion both in the UK and worldwide. The literature is vast. One classic text is Rogers (1967). Experiential learning is active learning undertaken through exercises and other activities designed, for example, to increase self-awareness or aid decision making.

See Chapter 12 on helping people to learn.

Deciding What to Change

Some clients could benefit from making several lifestyle changes to improve their health, and it can be tempting to try to address all of them at the same time. But people are often at different stages of readiness to change on different issues. For example, a person considering making improvements to his diet might be ready to make one change (such as eating more fruit and vegetables) but not ready to make others, such as changing to lower fat milk; an overweight person may be ready to take more exercise but not to change his eating habits. By writing down all the areas or issues that could be changed and asking ‘Are there any of these you think you could discuss changing?’, you can get agreement to discuss one particular topic (Rollnick et al 1999).

Ranking or Categorising

Ranking is a way of analysing an issue in order to distinguish the relative importance of different aspects. It is therefore useful for clarifying values. For example, in Exercise 1.1 in Chapter 1, readers are asked to rank aspects of being healthy. Health is a value and that exercise is designed to help readers to clarify which aspects of health they value most.

See Chapter 1, section on what does being healthy mean to you?

Another approach to increasing self-awareness and values clarification is to generate a list of items, and then code them into different categories. Exercise 14.1 illustrates this approach; it is designed to raise awareness of the link between enjoyment and health.

EXERCISE 14.1

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Enjoyment and health

Quickly list as many things as you can think of that you enjoy doing. Write them down the left-hand side of a piece of paper. On the right-hand side, code each item according to the following categories.

£ – any items that involve spending money.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access