Empiric knowledge development: conceptualizing and structuring

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

Looking at human behavior is like running into a cloud whose origins and direction is unknown. You can see the cloud, dynamic and three dimensional, but when you reach out to grab a handful to test you come away with nothing visible but a clenched fist. You may be buffeted by the forces within the cloud that moves on, still visible and dynamic and still three dimensional and you think “I can see the cloud, I can feel the forces it contains, but how do I study it when it refuses to lend itself to anything more than a fleeting encounter?”

Marjorie R. Wright (1966, p. 244)

The opening quote suggests that the discipline of nursing concerns phenomena that are rather elusive—phenomena that nurses know exist and deal with on a daily basis yet that are difficult to describe and fully understand. Nursing is often characterized as a human science, which means that its disciplinary knowledge focuses on phenomena and events that are very different from phenomena within the physical sciences. Understanding and developing shared knowledge about human responses to a life-changing event is much different from understanding how solid matter responds to the application of heat or force.

Research is the usual means by which nursing’s disciplinary knowledge within the empiric pattern is developed. The suffix re- means “again” as well as “back,” which implies that, in research, knowledge is generated by a backward look or “re-searching” in relation to the phenomena being studied. However, when one looks back at human behavior as described in a single research report, often what was found is no longer evident or has changed. Research findings change because human behavior is not static. To be sure, some phenomena in the human sciences are more “cloud-like” than others. Human behavior that is regulated by physical processes (e.g., behavior associated with cardiovascular function) may be more predictable than behavior that is regulated by perceptions of meaning. For example, we now understand that compromised circulatory function in the brain of an elderly person is likely to eventually cause perceptible mental changes. It is much more difficult to understand or know how a child whose parent has been diagnosed with a debilitating disease will experience hope and despair. This is because human behaviors related to hope and despair are closely linked with the child’s perceptions of the meaning of the parent’s illness; those perceptions, in turn, are dependent on factors that change over time.

This chapter deals with conceptualizing and structuring phenomena that are relevant to nursing as an approach to developing disciplinary knowledge. Nursing seeks to conceptualize and structure phenomena that are extremely elusive as well as phenomena that are more easily understood. As we explain in this chapter, however, even what seems to be easily understood can sometimes be elusive. The challenge when conceptualizing and structuring empiric knowledge is to realize that, in nursing—regardless of what is studied—the focus is on human behavior and human responses which are, as Wright establishes in her quote, rather cloud-like.

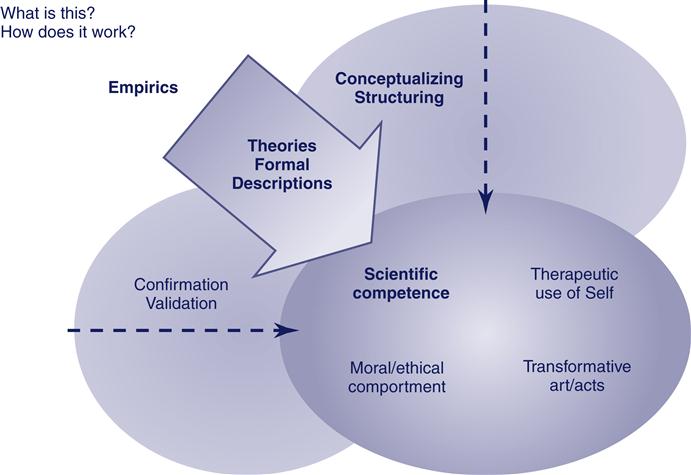

Figure 7-1 shows the empiric quadrant of our model for nursing knowledge development. As the critical questions “What is this?” and “How does it work?” are asked, the creative processes of conceptualizing and structuring are initiated. As with the other patterns, these questions are asked in the moment of practice as empiric knowledge is integrated with the other patterns of knowing. The questions can also be asked of the formal expressions of empirics apart from the immediate practice situation. As these questions are responded to, the creative processes of conceptualizing and structuring are engaged. Out of these creative processes comes the generation or reconfiguring of formal expressions of empirics.

The formal expressions of empiric knowledge include theories as well as other structured descriptions of empiric phenomena. As formal expressions are authenticated by confirmation and validation processes, the potential for scientific competence (i.e., the integrated expression of empirics in practice) is strengthened. In this chapter, we focus on the creative processes of conceptualizing and structuring empiric phenomena. The chapters that follow focus on other dimensions of the model’s empiric quadrant.

The following two processes are used for conceptualizing and structuring empiric phenomena: (1) creating conceptual meaning and (2) structuring and contextualizing theory. In the discipline of nursing, theory is generally considered the most formal and the most highly structured of the empiric knowledge forms, and it is this type of theory that we focus on in this chapter. However, there are many varieties of empiric knowledge to which these processes can also apply.

What is empiric theory?

The term empiric has a number of different meanings. From a traditional standpoint, empiric implies an objective, nontheoretic observation, which implies that meaning exists in what is observed apart from the interpretations of the observer. In a clinical context, the term is used to specify a treatment or an approach that has been demonstrated to be effective. From a philosophic perspective, empiric refers to that which is accessible to sensory perception, either directly or indirectly. Our definition is grounded in the philosophic meaning of the term: knowledge that is grounded in perceptual experience. This would include knowledge that is developed with the use of controlled experimental studies as well as a variety of naturalistic methods that rely on interacting with and understanding the nature of experience as it is perceived. In this and the remaining chapters of this book, we discuss empiric theory.

Like empirics, the idea of theory can be defined in many different ways within and outside of the discipline of nursing. This can be confusing, because each definition can be functional, depending on how you are using the term. It is a challenge to select the best definition when you are developing theory, because your definition will guide your methods of theory development. Your definition will also reflect your underlying beliefs and values related to science, knowledge, and what constitutes an adequate empiric method. You will see our values and beliefs reflected in our explanation of how we came to the definition that is used in this text.

Theory has common, everyday connotations that are apparent in phrases such as “I have a theory about that” or “My theory about x is… .” These usages imply that theory is an idea or feeling or that it explains something. In this text, we use a definition that is consistent with the more everyday meanings of theory as a collection of ideas or explanatory hunches. However, our definition goes beyond this to a characterization of theory as something that is deliberately designed for a specific purpose.

Beliefs about the nature of empiric theory arise in part from the various fields of inquiry from which nursing knowledge is developed. Some nursing theorists come from traditions in which the ideal of theory is logically linked sets of confirmed hypotheses. Others view theory as loosely connected ideas that are conjectured but not confirmed. Still others think of theory as philosophically based sets of beliefs and values about human nature and action. As a result, the nursing literature contains varying definitions of theory, but this diversity serves to stimulate the further understanding and development of theory. The following four definitions in the nursing literature emphasize different perspectives and different underlying values that involve theory. These definitions each highlight important aspects of theory that we draw on in our own definition:

• A logically interconnected set of confirmed hypotheses (McKay, 1969). This definition implies a specific form of expression that is based on rules of logic. It also requires that the hypotheses are tested and confirmed with the use of methods of scientific-empiric research to generate theory.

• A conceptual system or framework that is invented to serve some purpose (Dickoff & James, 1968). In this definition, the purpose for which a theory is created is emphasized. The term invented implies a creative process, although this may not necessarily involve the type of testing and confirmation that McKay suggests. This definition emphasizes the importance of the theory having a purpose.

• An imaginative grouping of knowledge, ideas, and experiences that are represented symbolically and that seek to illuminate a given phenomenon (Watson, 1985). Watson also emphasizes creativity. For Watson, the purpose for which theory is created is to enhance understanding of a given phenomenon. As Dickoff and James explain in their work, from their point of view, a theory’s purpose should be a specific practice-oriented application. For Watson, a theory fulfills the purpose of understanding what a phenomenon is, which may or may not have direct application in practice.

• Conceptual and pragmatic principles that form a general frame of reference for a field of inquiry (Ellis, 1968). This definition does not address a specific kind of purpose for theory, and it does not suggest any particular method for developing theory. For Ellis, theory provides a philosophic view that guides inquiry in a discipline. Theory contains abstract (conceptual) and pragmatic principles that provide a general frame of reference.

From our perspective, empiric theory is a creative and rigorous structuring of ideas. The ideas are expressed by word symbols that form a conceptual structure. The structure is created with the use of a method that draws on the creativity of the theorist. The concepts contained within the theory must be defined, and they must have a logical relationship with one another to form a coherent structure or pattern. Empiric theory is purposeful: theorists create the theory for some reason. Theoretic purposes may take many different forms, but the purpose needs to be clearly evident.

From our perspective, empiric theory is a creative and rigorous structuring of ideas. The ideas are expressed by word symbols that form a conceptual structure. The structure is created with the use of a method that draws on the creativity of the theorist. The concepts contained within the theory must be defined, and they must have a logical relationship with one another to form a coherent structure or pattern. Empiric theory is purposeful: theorists create the theory for some reason. Theoretic purposes may take many different forms, but the purpose needs to be clearly evident.

Theory is not a finalized prescription or a formula for practice; it cannot describe exactly what can be objectively observed. Instead, theory projects tentative ideas that open new perceptions and possibilities with regard to what might be beyond the common surface understandings of the world. Theory is grounded in assumptions, value choices, and the creative and imaginative judgment of the theorist. You may or may not share the values and views of the theorist, but your exposure to the theory and the views that it reveals can expand your own thinking about your experience, your profession, and the direction of your own work.

Our definition of theory is as follows:

Empiric theory: A creative and rigorous structuring of ideas that projects a tentative, purposeful, and systematic view of phenomena.

The word creative underscores the role of human imagination and vision in the development and expression of theory; it does not mean that “anything goes” or that theory is improvised. The creative processes that are required to develop theory also are rigorous, systematic, and disciplined, thereby yielding a well-developed conception that bears the mark of the creator. In our view, theoretic statements are tentative and open to revision as new evidence and insights emerge. The statements are developed toward some purpose or within a specific context. Our definition does not require that a hypothesis be tested before the statements can be considered as theory. Ideas that the creator systematically develops on the basis of experience and observation can be considered as theory before formal testing occurs.

Given our definition, it is possible to contrast how empiric theory differs from related terms such as science, philosophy, paradigm, theoretic framework, and model. Like the word theory, these terms are highly abstract and have many different meanings for different people and within the discipline of nursing. Sometimes the meanings overlap, and sometimes the meanings seem very different. When there are confusing overlaps and differences, you can resolve the confusion by clarifying commonly accepted disciplinary meanings and creating a reasonable definition that is appropriate for your purposes.

Your definitions cannot be arbitrary or simply based on your personal beliefs. Like our definition of theory, your definitions of any terms will reflect your beliefs. In addition, your definitions must be consistent with common threads of meaning that are generally accepted within the discipline and grounded in a logical rationale that is coherent to other members of the discipline. Definitions must also be suitable for the context in which they are created and the purpose that they serve. For example, if you are defining the word self-esteem for a research study, your definition might include the foundational meanings that are consistent with the tool that you are using to measure self-esteem. However, if you are defining self-esteem for a clinical project that is designed to assist women with the making of prenatal health choices, your definition may or may not reflect the underlying meanings of a specific measurement tool.

We have defined theory for the purpose of explaining to you, the reader, our view of what theory is, how to develop it, and how to evaluate it. Definitions of related terms help to make clearer the meaning of the central term (in this case, theory). Our definitions of several related terms for the context of this text are shown in Table 7-1. The definitions of related terms may not be universally accepted, but we believe that they are reasonable and that they reflect common meanings. In addition, no matter how rigorous the attempt to differentiate like terms by providing definitions, there will be elements of shared meaning among them.

TABLE 7-1

Conceptual Definitions of Terms Related to the Concept of Theory

| Term | Definition |

| Science | An approach to the generation of empiric knowledge that relies on accessible sensory experience to create knowledge and to form understanding. The term also refers to the results or products generated when the systematic methods of empirics are used. |

| Philosophy | A form of disciplined inquiry that discerns the nature of the world and of knowledge and knowing and that involves ways of discerning reality and principles of value. Philosophy relies on logic and reasoning rather than empiric evidence to create knowledge. |

| Fact | That which generally is held to be an empirically verifiable object, property, or event, which means that the phenomenon is experienced and named consistently and similarly by others in a given similar context. |

| Model | A symbolic representation of an empiric experience in the form of words, pictorial or graphic diagrams, mathematic notations, or physical material (e.g., a model airplane). |

| Theoretic or conceptual framework | A logical grouping of related concepts or theories that usually is created to draw together several different aspects that are relevant to a complex situation, such as a practice setting or an educational program. |

| Paradigm | A worldview or ideology. A paradigm implies standards or criteria for assigning value or worth to both the processes and the products of a discipline as well as for the methods of knowledge development within a discipline. |

In the following sections, important processes for conceptualizing and structuring empiric theory are addressed. Conceptualizing involves creative processes of making meaning; it involves exploring a wide range of possible meanings for a concept and creating a meaning that is relevant to your purpose. The structuring processes involve placing concepts into a structure and then placing that structure into a larger context.

Creating conceptual meaning

Creating conceptual meaning is a theory-building approach that depends on mental thought processes. The process of creating conceptual meaning carefully examines the ideas, perceptions, and thoughts that are generated when word symbols are encountered. To say that words are symbols means that words stand for or represent some experience or phenomena. In similar cultures, the meaning associated with word symbols is both common and unique. For example, in nursing, similar meanings for the word symbol “hypothermia” are shared among those who belong to the discipline. At the same time, a person’s own subjective meaning may be unique and more real to the individual than any other possible interpretation of the word. For example, if I am in a room with a comfortable ambient air temperature and announce that I am cold (i.e., mildly hypothermic) when everyone else in the room is comfortable, my own perception and experience of being cold is the most real to me, although I recognize that I am the only one who feels cold. When you are creating conceptual meaning for a theory, you are giving meaning to the word symbols within the theory. During this process, use your mental capacity to recognize when your own perceptions are unique and to assess the extent to which your unique experience represents an oddity as well as the possibility of a new prospect for others to consider.

Conceptual meaning does not exist as an unexplored reality to be objectively discovered; it is created and deliberately formed from experience. The process of creating conceptual meaning brings dimensions of meaning to a conscious and communicable awareness. The perceptions or meanings that any language or word symbol calls forth are limited when it comes to expressing the fullness of the experience that is represented. For example, when you encounter the word hope, you have a sense of what that word represents. That sense may be quite rich and full, but it is still limited in relation to the full range of meanings possible, because personal experience is limited and never encompasses the full range of possible meanings. The process of creating conceptual meaning makes it possible to expand what we understand about a phenomenon that goes beyond the simple definition of its word symbol and our unique perception of its meaning.

Word symbols and language call to mind unique yet common meanings, and language systems shape and create perceptions and meaning (Allen & Cloyes, 2005; Crowe, 2005; Muller & Dzurec, 1993; White, 2004). If someone is called “clever,” that person begins to form an awareness of self that may be affirming, but the word clever may not adequately express the person’s rich inner experiences and instead may trivialize how the person experiences the world. If a word represents a desired value, the meaning that is understood when the word is encountered contributes positively to self-awareness.

Although the process of creating conceptual meaning provides a foundation for developing theory and is a logical starting point for theory development, it does not necessarily have to be accomplished first. It is a process that can be performed by the beginning or advanced scholar and by the novice or expert practitioner. Although this process is critical to all theory development, it is often overlooked (Norris, 1982). Most theorists provide definitions of terms that are used within a theory, but forming word definitions is not the same as creating conceptual meaning. Conceptual meaning conveys thoughts, feelings, and ideas that reflect the human experience to the fullest extent possible, which is not possible with a definition. A word definition provides an anchor from which to situate common mental associations with a term; conceptual meaning displays a mental picture of what the phenomenon is like and how it is perceived in human experience.

What is a concept?

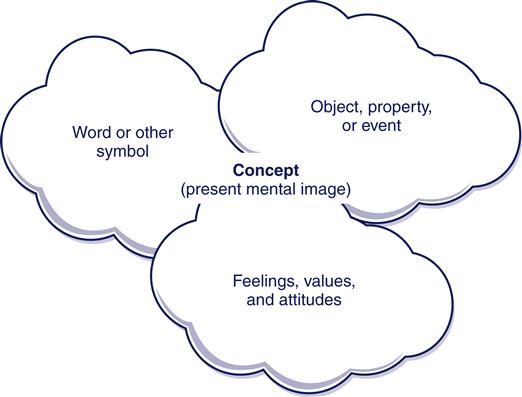

We define the term concept as a complex mental formulation of experience. By “experience,” we mean perceptions of the world, including objects, other people, visual images, color, movement, sounds, behavior, and interactions; in other words, we refer to the totality of what is perceived. Experience is considered empiric when it can be symbolically shared and verified by others with sensory evidence.

Figure 7-2 shows the three sources of experience interacting to form the meaning of the concept: (1) the word or other symbolic label; (2) the thing itself (object, property, or event); and (3) the feelings, values, and attitudes associated with the word and with the perception of the thing. As any one of these elements changes over time, the concept itself changes. Consider, for example, the concept of mouse. Until the 1980s, this word symbol was almost exclusively connected to a little critter that wreaks havoc in people’s basements and prompts wild screams of terror. In a very short time frame, this word symbol came to signify not only that little critter but also a very different object: a device that is used to navigate on a computer. At first, this device was thought to be optional and mainly useful for the playing of games. However, it quickly became not optional but necessary (which is an attitude or feeling), and it is certainly not an object that elicits screams and screeches. Almost any word could have been chosen for this little object, but its originators selected the word mouse, which derives from the resemblance of early models that had a cord attached to the rear part of the device (suggesting a tail) to the common mouse.

Conceptual meaning is created by considering all three sources of experiences related to the concept: the word, the thing itself, and the associated feelings (see Figure 7-2). The same word may be used to represent more than one phenomenon. For example, the word cup may be used to represent several different kinds of objects or ideas. Each use of the word carries with it different perceptions. If the object is a fancy teacup, a very different mental image forms than if the object is the cup into which a golf ball falls on a putting green. The word love, which is a more abstract concept, can be used to describe a feeling toward a parent, a child, a pet, a car, a job, a friend, or an intimate partner, with each use implying a different but related feeling. When creating conceptual meaning, you examine a range of applications for a word symbol, find what is common among all of the uses and what is different, and decide what elements of meaning are important for your purpose.

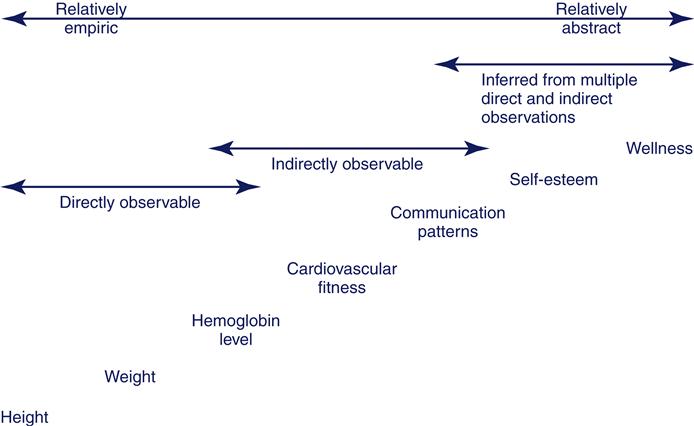

All concepts can be located on a continuum from the empiric (i.e., more directly experienced) to the abstract (i.e., more mentally constructed) (Jacox, 1974; Kaplan, 1964). In one sense, all concepts are both empiric and abstract. They are empiric because they are formed from perceptual encounters with the world as it is experienced, but they are abstract because they are mental images of that experience.

Some concepts are formed from very direct experiences that can be more readily verified by others. Others are formed from experiences that are commonly recognized but inferred indirectly. Figure 7-3 illustrates this continuum. Relatively empiric concepts are ideas that are formed from the direct observation of objects, properties, or events. As concepts become more abstract, they are inferred indirectly. The most abstract concepts are mental constructions that encompass a complex network of subconcepts.

The most concrete empiric concepts have direct forms of measurement. Concepts formed around objects such as a cup or properties such as temperature are examples of highly empiric concepts, because the object or property that represents the idea (i.e., the empiric indicator) can be directly experienced through the senses and confirmed by many different people. A relatively empiric property such as biologic sex can also be observed directly by noting the primary and secondary sexual characteristics that identify a person as male or female or—more precisely and especially if the sex is ambiguous—by identifying chromosomal patterns. Properties such as height and weight can be measured with standardized instruments.

As concepts become more abstract, their observational qualities (i.e., their empiric indicators) become less concrete and less directly measurable. The assessment of an abstract concept depends increasingly on indirect means. Although an indirect assessment or observation is different from direct measurement, it is considered a reasonable indicator of the concept. An individual’s hemoglobin level is representative of a concept that cannot be directly observed but that can be indirectly measured with the aid of laboratory instruments. This type of measurement depends on more complex and less direct forms of instrumentation.

Cardiovascular fitness is an example of a concept that is middle-range on the empiric–abstract continuum. Concepts increase in complexity in this range, and several empiric indicators must be assessed. Because no actual object that can be called cardiovascular fitness exists, a definition is required if we are to know what it is. Although definitions for less empirically based concepts are thoughtfully formulated, they are arbitrary, because many different definitions could be chosen. As concepts become increasingly abstract, definitions become more dependent on the theoretic meaning of the concept and the purpose for defining it.

Self-esteem is an example of a highly abstract concept for which there is no direct measure. The instruments or tools that are developed to assess self-esteem depend on theoretic definitions that serve a specific purpose and that are built on many behaviors and personality characteristics that experts agree are associated with that concept. Ideas about these characteristics may be derived from a theory or from concept clarification. Each behavioral trait that is contained in the tool can be considered as a partial indicator of self-esteem. When the composite behaviors and personal characteristics are built into an assessment tool, it is usually a more adequate indicator of the abstract concept than any one behavior taken alone. The composite score obtained from the tool is then considered to be a measurement that has been constructed as an empiric indicator.

Highly abstract concepts are sometimes called constructs. Constructs are the most complex type of concept on the empiric–abstract continuum. These concepts include ideas with a reality base so abstract that it is constructed from multiple sources of direct and indirect evidence. An example of a construct is wellness. Although the idea of wellness exists, it cannot be directly observed. Figure 7-3 illustrates the idea that highly abstract concepts are constructed from other concepts. All concepts shown on the continuum (as well as others) can be included in the concept of wellness.

Some abstract concepts have little meaning outside of the context of a theory. For example, Levine (1967) coined the word trophicogenic to mean “nurse-induced illness.” Rogers (1970) discussed three principles of homeodynamics. Rogers’ term homeodynamics is a combination of the Latin root word homeo, which means “similar to” or “like,” and the common English term dynamics, which means “pattern of change or growth.” The reader can infer the meaning of “change processes” for the term homeodynamics, which is consistent with Rogers’ intent.

Abstract concepts may also acquire additional meanings through gradual transfer into common language usage. Freud’s concept of ego is an example. The word ego once had no common meaning outside of Freud’s theory, but today, with gradual changes in its meaning and broad usage outside of the theory, almost everyone who speaks American English and many other English speakers around the world know the meaning of the phrase a big ego.

A single phenomenon can also be represented by several different words. Each word conveys a slightly different meaning and often reflects nuances that relate to socially derived value meanings. For example, the words luxury car, Model T, and hot wheels all refer to one basic thing: an automobile. The use of any of these words to describe an automobile conveys the perspective or values of the person who is using the word as well as the features of the object itself. As the words acquire contextual and value meanings, they shift further toward the abstract.

Feelings, values, and attitudes are inner processes that are associated with experiences and words. For example, the word mother carries feelings, values, and attitudes that form in human experience with an actual person. Varying experiences with a certain mother (the person) account for a range of feelings that different people associate with the word mother. At the same time, the human meaning of the concept mother is formed from shared cultural and societal heritages. A concept such as mother, which can carry specific or highly complex meanings, changes in its level of abstraction, depending on the context of usage.

Many nursing concepts are highly abstract. Although theory and other common forms of empiric knowledge (e.g., models, frameworks, descriptions) incorporate and depend on highly empiric facts, nursing theory does not generally reflect factually based concepts.

Although it usually is not possible or necessary to identify precisely where concepts fit on the empiric–abstract continuum, it is important to understand that concepts vary in the degree to which they are connected to what is perceived as experience and the extent to which their meaning is mentally constructed. When you begin to study an abstract concept, it is natural to wonder why it is difficult to grasp the meaning of the term and to understand all that is conveyed by the concept.

Methods for creating conceptual meaning

Creating conceptual meaning produces a tentative definition of the concept and a set of tentative criteria for determining whether the concept is meaningful in a particular situation. We use the word tentative because both the definition and the criteria can be revised. The term tentative does not mean that anything goes or that any definition that suits the author will do. However, it does mean that the definition is open and can be changed as new insights and understandings come to light. This process is a deliberative, disciplined activity. The person who is creating meaning draws on many information sources, examines many possible dimensions of meaning, and presents ideas so that they can be tested and challenged in the light of the purposes for which the conceptual meaning is intended.

There are various methods for creating conceptual meaning, each of which has advantages and drawbacks (Beckwith, Dickinson, & Kendall, 2008). Norris (1982) described several methods for concept clarification. Walker and Avant (2004) described a method of concept analysis that was based on the work of Wilson (1963). Morse (1995) described methods of concept development and analysis that draw on qualitative and quantitative research approaches to validate meanings that are projected by analytic processes. Moscou (2008) described a method of concept analysis that was based on research evidence. Rodgers and Knafl (2000) propose an “evolutionary” method of concept analysis that recognizes that conceptual meaning is dependent on context. Morrow (2009) described a creative process for selecting and conceptualizing meaning on the basis of the contemplation of a painting and then placing the meaning within a nursing framework.

Our approaches to creating conceptual meaning are similar to some of the traits described by other authors, but our approach is based on the view that meanings are created for a particular purpose and do not remain static but rather change over time and in different contexts. Therefore, it is not possible to make a claim that a concept is mature or sufficiently developed. Meanings are not inherent in objects or in a reality that exists independently; rather, they are shaped and formed in relation to a particular purpose and a particular context. For example, consider again the example of the word mouse and the two very different conceptual meanings that it carries. The conceptual meanings that you would bring with you when you go into a pet store with the intention of purchasing a mouse and that you would bring with you when you go into a computer store to purchase a mouse are shaped by the purpose of your shopping trip and the type of store that you enter to achieve this purpose.

When creating meaning, a wide variety of sources and methods can be used. There is no recipe or specific method to follow, and the approach to creating meaning can shift according to the purpose for which your concept is intended or used. The following sections provide guidelines that you can select and adapt as needed.

Selecting a concept

Selecting a concept is a process that involves a great deal of ambiguity. Concept selection is guided by your purpose and expresses values related to your purpose. If you are a student in a nursing class, your concept selection may be guided by expediency as well as interest. If you are a postdoctoral student, you may create conceptual meaning to resolve a dilemma that you encounter when moving through the research process.

Values that influence your selection of a concept include your beliefs and attitudes about the nature of nursing. We believe that concepts should justifiably relate to the practice of nursing. An example would be a concept that represents a human response to health or illness, such as fatigue. Characteristics of clients such as hardiness may also be selected, particularly if they are important determinants of health. Characteristics of nurses, care systems, or nurse-client-family interaction may also be chosen if they are related to nursing’s purpose of creating health and well-being.

Often, many different disciplines share interest in the same concept. To claim that a concept is justifiably related to nursing does not mean that it is only a nursing concept. For example, fatigue is a concept that is of interest to nurses but also to physicians and clinical pharmacists. Fatigue becomes more of a nursing concept when a conceptual meaning is created for fatigue that is useful and important within a nursing context, such as when the meaning reflects what nurses have control over and what they do. Locating the concept of fatigue within a theory that conceptualizes fatigue as a human response to chemotherapy and developing criteria for fatigue that can be assessed and alleviated by oncology nurses makes it a nursing concept. Physicians might develop criteria for fatigue that index it in relation to the safety of continuing a regimen of treatment (i.e., their role), whereas clinical pharmacists might create criteria that would assist drug manufacturers with formulating pharmaceuticals that are more effective for alleviating fatigue.

Thus, when choosing concepts, the role and context of nursing is important to the choice. However, it is more important as you create conceptual meaning to make choices that help to ensure the meaning that is created is useful to nurses as they manage human responses and help persons to move toward health. The important question is not “Is this a nursing concept?” but rather “Is this concept of interest to nursing and is the meaning created useful for nursing’s purposes?”

Sociopolitical considerations will also influence your choice of a concept, often in ways that are subtle and difficult to perceive. For example, if you choose to examine the concept of transition for daughters who must place their mothers in nursing homes, you will eventually come to examine the consequences of women’s caretaking within a society that devalues its elders and that disregards women’s work when caring for aging parents by not considering it to be real work.

Some concepts are not appropriate as a focus for the process of creating conceptual meaning. Some are too empirically grounded, and others are too expansive to yield a useful outcome. Concepts that represent empirically knowable objects (e.g., antiembolic stockings) are usually not good choices, because they are highly empirically grounded and can be demonstrated by a display of the thing itself. You do not need to examine the concepts to understand their meanings, and having criteria for recognizing them will not help you clinically in any significant way. Broad concepts such as caring and stress pose another set of problems. Because these types of concepts are so vast, creating meaning can result only in a broad understanding that omits detail and that may be misleading. This is not to say that creating conceptual meaning for very narrow or broad concepts is never useful, and, for some purposes, it may be justifiable. In our experience, the concepts that are most often amenable to the creation of conceptual meaning are those in the middle range. It often is helpful when choosing a concept to place it within the context of use to narrow its scope in relation to your purpose.

It often makes sense to choose a concept that is poorly understood or that tends to have competing or confusing meanings. However, most concepts carry a certain degree of ambiguity, and your meanings will alter as contexts for use change. Moreover, much of what is in the literature about concepts will be found to be inadequate or erroneous when you examine the concept in a new light. For example, much of the early information about fatigue was generated from research on airplane pilots and proved to be inadequate for understanding cancer fatigue. As a result, nurses began to generate knowledge about this particular type of fatigue. Remember that other disciplines do not have the same perspectives and motives for generating conceptual information as nursing does. Although knowledge of nursing concepts within other disciplines may be useful, these other circumstances need to be carefully examined. Other disciplines have a different perspective, and scholars in those disciplines are not likely to take into account perspectives that are common to nursing. Their work can inform nursing perspectives, but usually the conceptual meanings derived from other disciplines will not be adequate for nursing purposes.

With these guidelines in mind, you can select a word or phrase that communicates the idea that you wish to convey. Despite your best efforts to make the perfect initial choice, that choice will probably change as you explore various meanings. Trying out alternative words becomes part of the process itself. For example, there is no adequate single term for the idea expressed by the phrase the use of humans as objects. The term objectification is close, but it implies some experiences that do not involve the use of humans. The process of working with various terms related to this idea will help you to explore various meanings that are possible. Because the experience is not adequately expressed in common language, words may seem quite inadequate at first. You may select a common word for a concept and eventually assign a specific definition to the word to suit your particular purposes, or you may borrow a word from another language, combine two or more common words to specify a particular meaning, or make up a phrase or a word. Many significant concepts for nursing have not been adequately named. As nurses engage in processes for creating conceptual meaning, a more adequate language for nursing phenomena will be created.

Clarifying your purpose

To provide a sense of direction, you must know why you are creating conceptual meaning. One purpose is to set boundaries or limits so that you do not become hopelessly lost in the process. For example, your purpose might be to work with the concept dependence for a research project. Eventually you will need a clear conceptualization of dependence as well as ideas about how to measure or assess it. Another purpose might be to differentiate between two closely related concepts, such as sympathy and empathy. In this case, your concern is to create definitions that differentiate on the basis of a thorough familiarity with the meanings that are possible.

Another reason for creating conceptual meaning is to examine the ways in which concepts are used in existing writings. For example, the concept of intuition commonly appears in nursing literature with many different but related meanings. The meanings that are conveyed reflect different assumptions about the phenomenon. As you become aware of these meanings, you can explore the extent to which the meanings are consistent with your own purpose.

Other purposes for creating conceptual meaning include generating research hypotheses, formulating nursing diagnoses, and developing computerized databases for clinical decision making. Creating conceptual meaning is also a valuable process for learning critical thinking skills (Kramer, 1993). When you keep your purpose as clear as possible, you have an anchor that provides a sense of direction when you seem to be hopelessly lost.

Sources of evidence

After a concept has been selected, the process of creating conceptual meaning proceeds with the use of several different sources from which you generate and refine criteria for the concept. You may involve others in the process to review and respond to your work as a way to generate new understanding and insights. The sources that you choose and the extent to which you use various sources depend on your purposes. Early during the process of gathering evidence for the concept, tentative criteria are proposed, and those criteria are refined in the light of additional information provided by continuing gathering of evidence. We recommend beginning the process of criteria formulation early so that useful information is not lost. Criteria are succinct statements that describe essential characteristics and features that distinguish the concept as a recognizable entity and that differentiate this entity from other related ideas.

Exemplar case.

An exemplar case is a description or depiction of a situation, experience, or event that satisfies the following statement: “If this is not x, then nothing is.” The case can be drawn from nursing practice, literature, art, film, or any other source in which the concept is represented or symbolized. If the case is depicted as an object or in some form of media, many rich aspects of the phenomenon can be conveyed by displaying the media for others to experience. Regardless of the format used for presentation, the case is selected because it represents the concept to the best of your present understanding. For concrete concepts such as cup, an exemplar case is relatively easy. An ordinary teacup, for example, can be presented for others to see and hold. The people who examine the object can then verify, “If this is not a cup, then nothing is.” To demonstrate the concept red (a property), a model case is more difficult. You can physically present to the group something that you perceive as being red in color and find out whether the group agrees that this is what its members would also perceive as being red. However, a more precise and consistent identification of red would result from measurement with the use of a spectrophotometer.

When you deal with highly abstract concepts, the task of constructing and selecting exemplar cases is even more difficult, and often these concepts can only be measured indirectly. Many such measurements depend on scales that rely on self-report. For example, the concepts of anxiety and pain are typically measured by self-report rating scales. Usually, exemplar cases of abstract concepts involve experiences and circumstances that are described in words. Exemplar cases may be created from your own experience, or you may find cases in the literature that have been constructed or described by others. For example, to demonstrate an abstract concept such as sorrow, a scenario from a novel or film or a rich description of an experience from your practice can be shared with others who respond to the scenario as a representation of the phenomenon of sorrow.

If you create your own exemplar case, work with your ideas and revise your description until you are satisfied that the case fully represents your concept. For a concept such as mothering, your exemplar case might describe the following event: an infant cries, and an adult picks up the infant. The event is a start, but when you share your case with others, they might object, saying that this description represents only the physical act of picking up a crying child and does not necessarily demonstrate mothering. Your exemplar case develops until there is enough substance that people respond to the case by forming a mental image of mothering. As you build on the scenario of an adult picking up an infant to represent mothering, you could include various circumstances, behaviors, motives, attitudes, and feelings that surround the act of picking up the infant. You paint a picture or tell a story so that people can confirm that this is indeed mothering. As this and other exemplar cases are created, you can compare various meanings in the experience and define what is common and what is different about the various cases that you consider.

It often is useful to alternatively include and exclude various features of exemplar cases to reflect on how central each feature is to the meaning you are creating. In the exemplar case of mothering, the adult initially might be portrayed as female. Later, you might portray a male in the same case. In the absence of any evidence one way or the other, you might tentatively decide that the idea of mothering that you are creating will be deliberately limited to instances that involve women. Because your decision is tentative, you can change your construction for another purpose or circumstance. You can acknowledge the fact that some men mother but that, for your purpose, your idea deliberately includes the experience of women.

While you are working with exemplar cases, pose the following question: What makes this an instance of this concept? The responses to this question form the basis for a tentative list of criteria. During the early stages, the criteria may be quite detailed, and they may be the essential characteristics associated with the concept, given the meanings that you deliberately decide to include. The criteria are designed to make it possible to recognize the concept when it occurs and to differentiate this concept from related concepts. For example, in the case of mothering, you would want to be able to recognize mothering when it happens and distinguish mothering from related phenomena such as caring, nurturing, or helping.

Impressions regarding the criteria begin to form as you work with your exemplar case. You develop ideas about which features are essential for your purposes and why as well as their qualitative characteristics. These ideas become the criteria for the concept. Sometimes exemplar cases are presented after clarification is complete. In these instances, the exemplar case is similar to a definitional form for the concept. Here we use exemplar cases as a way to create meaning rather than to represent it.

Definitions.

Two sources that provide information about conceptual meaning are definitions and word usages of the concept you are exploring. Existing definitions are often circular and do not give a complete sense of meaning for the concept, but they do help to clarify common usages and ideas associated with the concept. Existing definitions often help to identify core elements of objects, perceptions, or feelings that can be represented by a word. They are also useful for tracing the origins of words, which provides clues about core meaning.

Dictionary definitions provide synonyms and antonyms and convey commonly accepted ways in which words are used. They are not designed to explain the full range of perceptions associated with a word, particularly a word that has a unique use within a discipline or that represents a relatively abstract concept.

Existing theories provide a source of definitions that sometimes extend beyond the limits of common linguistic usage. Theoretic definitions and ways that concepts are used in the context of the theory convey meanings that pertain to the domain of the discipline from which the theory comes.

For example, the term mother as defined in the dictionary refers to the social and biologic role of parenting and includes a few characteristics of the role, such as authority and affection. In the context of psychologic theories, the meanings that are conveyed with respect to the values, roles, functions, and characteristics of people who are mothers are almost endless and include parenting, physical care, guilt, responsibility, power, and powerlessness.

Visual images.

Visual images that already exist, such as photographs, cartoons, calendars, paintings, and drawings, are useful sources for creating conceptual meaning (Morrow, 2009). If you are choosing existing images, they may be explicitly labeled or named as the concept of interest, or you may judge them to reasonably represent it. If you can find images that others have explicitly labeled as an instance of the concept, such as a picture that the artist labels “Sorrow,” the artist’s linking of the visual image to the concept provides further validation of the meaning of the concept, enriches the range of meaning, and helps to minimize any bias inherent in your own views of the meaning of the concept. In some instances, you or others might deliberately create images that represent the concept that is being clarified rather than use existing sources.

Whether you personally create and examine an image or ask others to create images, the idea is to compare them for similarities and differences. For example, advertisements and photographs that document the concept depression provide information about conceptual meaning. Often, visual imagery will highlight some aspect of the concept that is significant. On other occasions, visual imagery may raise questions about the essential nature of the phenomena that are important to the refinement of criteria. Visual images that represent concepts very well also highlight difficulties with expressing meaning linguistically. A photograph may express rich dimensions of the concept of dignity, yet the essence of dignity expressed by the photo is impossible to describe. This is an example of how aesthetic expressions of concepts contribute to empiric knowledge.

Popular and classical literature.

A variety of literature resources can provide information about conceptual meaning. Literature reflects meanings that arise from the culture and provides rich sources of exemplar cases for concepts. Classical prose and poetry are often good sources of meaning for concepts that are used in nursing. For example, images of love and longing may be found in the poetic works of Emily Dickinson. Louisa May Alcott’s classic book Little Women provides information about the nature of intimacy and caring. The popular current literature is also a source of valuable data about conceptual meaning. Popular self-help books on topics such as overcoming negative thinking and codependency often can clarify commonly understood (or misunderstood) conceptual meanings. Fairy tales, myths, fables, and stories provide relevant insights, depending on the concept that you are exploring. Usages for words that are expressed in popular jargon and cartoons may highlight borderline meanings. For example, when a 5-year-old child jumps up and down and exclaims, “I’m so anxious for my birthday to be here!” the meaning of anxious is not the same meaning that concerns nurses. What the child’s usage does convey is the physical agitation that accompanies the experience of anxiety within the context of nursing practice.

Music and poetry.

The imagery of music or poetry may be useful for the creation of conceptual meaning. You can find music or poetry by seeking out lyrics or titles that name the concept under consideration. The music itself or the metaphoric images in the title or lyrics may reasonably suggest the concept. Music and poetry can effectively convey meanings through rhythm, tones, lyrical or linguistic forms and metaphors, or musical moods that reflect experiences in life events with which nurses deal. For example, the Shaker folk tune “Simple Gifts” suggests criteria for concepts of authenticity, genuineness, centeredness, and community. The tune itself conveys a sense of inner happiness and peace; the lyrics reflect relationships between inner peace and the ability to build strong relationships. The popular Cole Porter song “Don’t Fence Me In” conveys through its musical mood, rhythm, and lyrics what it feels like to be confined emotionally and projects a yearning to be free.

Professional literature.

The meanings of concepts can be explored from within the context of the professional literature. This literature often provides meanings that are pertinent to the practice of nursing. For example, philosophers as well as nurses have written about the concept of presence as a way of being with another. When the work of a scholar in another discipline coincides with your experience as a nurse, the work of other scholars can augment your conceptual meaning. When you find contradictions with your experience as a nurse, the contradictions prompt you to clarify your own insights about the phenomenon.

Anecdotal accounts and opinions.

Peers, coworkers, hospitalized individuals, other professional workers, and people who are not connected to nursing can provide valuable information about the meaning of a concept. It may be useful to seek others’ opinions about the meaning of a concept, particularly if your direct experience with the concept is limited. Nurses who work with the concept daily may be able to shed light on nuances of meaning that will markedly affect how meaning is integrated into your theory. For example, a nurse who works with people whose lung function is severely compromised might observe that anxiety, although usually characterized by increased activity, evokes a different reaction in these patients. Rather than random activity, anxiety may be accompanied by a deliberate quieting of behavior to conserve energy. Asking others to share their ideas about a concept is an informal exploration that is different from standard research procedures that might investigate conceptual meaning. Rather, it is an exploration of the opinions and understandings of others to ground your meaning in everyday perception or to test your professional meanings in the light of everyday assumptions about a phenomenon.

Methods for testing tentative criteria and the exemplar case

As you examine various sources of evidence, you will begin the process of testing the soundness of your conceptualization that has been created in the light of your purpose. You may find alternative meanings that are reasonable or plausible but that are not well suited for your purpose. For example, for someone who is interested in a cup to be used for the purpose of drinking liquids, a golfing green cup, although a plausible instance of the concept of cup, does not have the defining features required for drinking liquids. To stimulate your thinking about nuances of meaning, you can turn to a number of cases that challenge your conceptualization and consider alternative contexts.

Contrary cases.

Contrary cases are those cases that are certainly not instances of the concept. They may be similar in some respects, but they represent something that most observers would easily recognize as significantly different from the concept you are considering. For more concrete concepts, contrary cases are relatively easy. A saucer or a spoon can be presented, and most observers in Western cultures would agree that these things are not cups. A spoon may hold liquids that people sip, but it is not a cup; a saucer that a cup sits on is also clearly not a cup. A contrary case for the color red might be the color green. For the concept of restlessness, calmness could be presented as a contrary case.

As you consider contrary cases, ask the following: What makes this instance different from the concept that I have selected? By comparing the differences between exemplar and contrary cases, you will begin to revise, add to, or delete from the tentative criteria that are emerging. If your purpose includes designing an exemplar case for your concept, you also might use this information to refine the exemplar case. For example, one of the traits that distinguishes a cup from a saucer or a spoon is the shape of the cup. You may already discern that this feature is essential by looking only at the cup. When you see the spoon and saucer, however, the shape stands out in sharp contrast, and your description of essential features of the shape of the cup can be more complete and precise. As you compare the objects, you may also decide that the volume of liquid that a cup holds is an important distinguishing characteristic. Later, when you consider miniature teacups as cases, you might decide that volume is not an essential quality, especially if your other criteria are sufficient to distinguish which objects can be considered cups, which is your purpose.

Sometimes, when creating narrative contrary cases, the tendency is to simply reverse the situation depicted in the exemplar case. Usually this does not add new information of significance for creating conceptual meaning. If you are having difficulty with constructing a negative case, ask someone else to suggest a contrary case or something that is definitely not what you are trying to describe. Sometimes you can locate a contrary case in the literature. Contrary cases that contribute to meaning often reveal important aspects of the exemplar case that are hidden in assumptions that you may be making about the concept.

Related cases.

Related cases are instances that represent a different but similar concept. Related cases usually share several criteria with the concept of interest, but one or more criteria will be particularly associated with the model cases to distinguish them from the related cases. A different word is generally used to label the related instances. If you find that one word is typically used to refer to essentially different phenomena, you may need to select language for your concept that differentiates it from the related meanings. For example, if you were focusing on the concept of love between a parent and child, you may need to use the word label parental love to signify that you see essential differences between this experience of love and other related experiences of love.

In the case of a cup, you might consider a drinking glass. For the concept of red, you might consider a red-orange hue or magenta. For the concept of mothering, you could design a case of child tending that would be similar to the exemplar case. You might make a childcare worker the adult or substitute an elderly person for the infant. Again, you consider differences and similarities between the exemplar and the related cases and revise the tentative criteria to reflect your new insights.

Borderline cases.

A borderline case is usually an instance of metaphoric or pseudo applications of the word. A borderline case is found when the same word is used in a different context. For example, if you are examining the concept of fatigue in chronic illness, a useful borderline case of the use of the term fatigue would be “military fatigue clothing.” Poetry and lyrics to music provide rich sources of metaphoric uses of words. In the evolution of language, the metaphoric meanings of words carry powerful messages that often persist as new usages emerge and thus illuminate the core meaning. The metaphoric meanings for the concept of red are excellent examples. Red as a word and as a color has become, in Western culture, a metaphoric symbol for communism, violence, passion, and anger. To give a “cup of cheer” is an exemplary borderline usage of the term cup. This highlights the feature of cups as being capable of holding something.

Slang terms and terms that are used to describe technologic operations or features are rich sources of borderline cases when they are first entering the language. After they become well accepted, they are no longer borderline; they move to more central conceptual meanings, and they sometimes even become exemplary cases. Slang, which can develop from a quirky application of a word, provides rich sources of borderline cases. The language that emerges to refer to new technology is also a rich source of borderline cases. During the early 1990s, the word web probably would have prompted a mental image of something that a spider creates, and a reference to the Internet would have been considered a borderline case. By the end of the 1990s, the word web was so fully associated with the Internet that it might have become a model case of web.

For the concept of mothering, a borderline case might be a computer motherboard, because this term and its related concept are not part of the typical computer user’s conceptual realm and remain primarily technical. You might choose this borderline usage to help clarify features of the concept of mother that can be seen as foundational to the concept of mothering. These features could include the central importance of the mother in some cultures for defining the scope of relationships or structuring the energy of all relationships within the system. Ask what happens to your meaning if you perceive mothering as a process that structures and directs the nature of relationships in a system.

Paradoxic cases are variants of borderline cases that are useful to highlight the central meanings of concepts. Paradoxically, these cases embody elements of both exemplar and contrary cases. For example, when exploring the meaning of dignity, you might create a case in which actions that violate dignity occur to preserve a central feature of dignity. Your case might be the emergency cardiopulmonary resuscitation of a person in a public space to preserve the life of that person. Such a case is paradoxic in that it violates some criteria for dignity but highlights the importance of a central criterion for discerning the concept.

You will probably invent other varieties of cases during the process of creating conceptual meaning. How the cases are classified is not critical. Rather, their important function is to assist you with discerning the full range of possible meaning so that you can design a meaning that is useful for your purpose. Although creating conceptual meaning is a rigorous and thoughtful process, cases are somewhat arbitrary, and they are historically and culturally situated. What you call them is not essential to the process; what is important is the meaning that you derive from the conceptual exploration and the investigation.

Exploring contexts and values.

Social contexts within which experience and the values that grow out of experience occur provide important cultural meanings that influence the mental representations of that experience. For example, consider the concept of judgment if you are a student taking an examination, a real estate agent assessing a home for sale, an official scoring a gymnastics meet, or a magistrate preparing to impose a sentence. When you explore the various meanings acquired by virtue of the context, you probably will become aware of meanings that you previously had not considered.

One way to imagine various contexts is to place your exemplar cases in different contexts and ask the following: What would happen in a different situation? You mentally imagine the practical outcomes of your conceptual meaning in its context. For example, if you place your exemplar case of the color red in the context of a magazine advertisement, what symbolic meaning is conveyed? What advertising results does the advertiser intend? If the color red is placed in the context of traffic signs and symbols, what meaning does the color now convey? What behavioral responses do you now expect? What about a woman who is wearing a red suit in a boardroom where everyone else is dressed in dark suits? As you consider various possible combinations of context, you will clarify how meanings are influenced by context.

Placing the concept in a subtly differing context also reveals values. The concept of mothering has a relatively positive connotation for most people. Most people agree that humans require “good” mothering to grow and develop adequately. However, people differ widely with regard to what they consider to be good mothering; these differences often have to do with the cultural context. For example, there probably would be considerable disagreement regarding whether what happens in a schoolroom, in a hospital, or in counseling can be considered mothering. What is considered mothering reflects deeply embedded cultural values. When you consider your exemplar case being placed in several different social contexts, you create an avenue for perceiving important values and making deliberate choices about them.

Formulating criteria for concepts

We focus on criteria as an expression of conceptual meaning because they are a sensitive and succinct form for conveying essential conceptual meaning. Criteria are particularly useful as tools to initiate other processes of empiric theory development. Your exemplar case is itself a full expression of conceptual meaning, but the criteria make explicit the features and characteristics of the exemplar case that represent your conceptual meaning. Other forms of narrative, diagrams, and symbols can express meanings that move beyond the limits of empirics alone.

Criteria for the concept emerge gradually and continuously as you consider definitions, various cases, other sources, and varying contexts and values. As you develop the criteria, you will naturally refine them so that they reflect the meaning that you intend. Criteria often express both qualitative and quantitative aspects of meaning and should suggest a definition of the word. Because criteria are more complex than a limited word definition, they amplify the meaning and suggest direction for the processes of developing theory.

To illustrate the function of criteria for a concept, consider how you might convey the idea of one U.S. dollar in coins to a person who is not familiar with American money. One way is to present all possible combinations of coins to the individual, who then memorizes the combinations to consistently collect the right coins together to yield the equivalent of a dollar. Another approach is to provide guidelines that enable the individual to recognize and compose the various combinations independently. An exemplar case might involve the use of three quarters, one dime, two nickels, and five pennies. Because many other combinations are possible, criteria are created from the exemplar case to cover all other possible combinations. The exemplar case is chosen deliberately to include all of the types of coins available so that, when examining the case, several characteristics of all possibilities emerge. One feature is that the units of the various coins add up to an equivalent of 100 pennies, which is the smallest possible coin value. However, this criterion alone may not be sufficient for someone who is not familiar with this monetary system, and other criteria are created to ensure that all other possible combinations are recognized. You might consider the weight of the possible coin combinations, the colors of the coins, their metallic makeup, or the exchange value of each coin. All of these features may be used, but the criteria should convey as simply as possible the information that is needed by a novice to collect one U.S. dollar in coins. The fact is that any color combination or any number of coins up to 100 may be used as criteria. The metallic content of the coins might serve as an adequate criterion and may even be the most precise of all possible criteria. However, if your purpose is to assist a person from another country with understanding how to make a dollar’s worth of change, you would not select the metallic content as a criterion, because it is impractical for that purpose.

For concrete objects, the criteria may be relatively simple. For the concept of a cup, examples of criteria might include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree