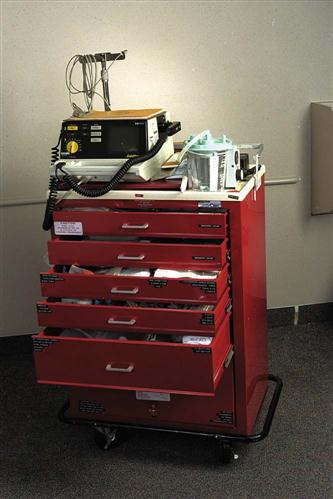

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care. 3. Describe patient safety factors in the medical office environment. 4. Evaluate the work environment to identify safe and unsafe working conditions. 5. Identify environmental safety issues in the healthcare setting. 6. Develop environmental, patient, and employee safety plans. 7. Discuss fire safety issues in a healthcare environment. 8. Demonstrate the proper use of a fire extinguisher. 9. Describe the fundamental principles for evacuation of a healthcare facility. 10. Role-play a mock environmental exposure event and evacuation of a physician’s office. 11. Discuss the requirements for proper disposal of hazardous materials. 12. Define the important features of emergency preparedness in the ambulatory care setting. 13. Maintain an up-to-date list of community resources for emergency preparedness. 14. Describe the medical assistant’s role in emergency response. 15. Summarize the typical emergency supplies and equipment. 16. Demonstrate the use of an automated external defibrillator. 17. Summarize the general rules for managing emergencies. 19. Recognize and respond to life-threatening emergencies in the ambulatory care setting. 20. Perform professional-level cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). 21. Administer oxygen through a nasal cannula to a patient in respiratory distress. 22. Identify and assist a patient with an obstructed airway. 24. Assist and monitor a patient who has fainted. 25. Control a hemorrhagic wound. 26. Apply patient education concepts to medical emergencies. 27. Discuss the legal and ethical concerns arising from medical emergencies. arrhythmia (uh-rith′-mee-uh) An abnormality or irregularity in the heart rhythm. asystole (ay-sis′-toh-le) The absence of a heartbeat. cyanosis (si-an-oh′-sis) A blue coloration of the mucous membranes and body extremities caused by lack of oxygen. diaphoresis (di-uh-fuh-re′-sis) The profuse excretion of sweat. ecchymosis (e-ki-moh′-sis) A hemorrhagic skin discoloration commonly called bruising. emetic (eh-met′-ik) A substance that causes vomiting. fibrillation Rapid, random, ineffective contractions of the heart. hematuria (hi-ma-tuhr′-e-uh) Blood in the urine. idiopathic Pertaining to a condition or a disease that has no known cause. mediastinum (meh-de-ast′-uhn-um) The space in the center of the chest under the sternum. myocardium (my-oh-kar′-de-um) The muscular lining of the heart. necrosis (neh-kroh′-sis) The death of cells or tissues. photophobia An abnormal sensitivity to light. polydipsia Excessive thirst. thrombolytics Agents that dissolve blood clots. transient ischemic attack (TIA) Temporary neurological symptoms caused by gradual or partial occlusion of a cerebral blood vessel. Cheryl Skurka, CMA (AAMA), has been working for Dr. Peter Bendt for approximately 6 months. During that time, a number of patient emergencies have occurred in the office, and even more potentially serious problems have been managed by the telephone screening staff. Cheryl is concerned that she is not prepared to assist with emergencies in the ambulatory care setting. She decides to ask Dr. Bendt for assistance, and he suggests that she work with the experienced screening staff to learn how to manage phone calls from patients calling for assistance. Dr. Bendt is participating in a community-wide preparedness effort focused on both natural and human-made disasters, and he expects his practice and employees to be ready to respond if needed. This includes both creating plans to maintain the safety of patients and employees in the facility and providing assistance as needed in a community emergency. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • What should Cheryl learn about the medical assistant’s responsibilities in an emergency situation? • What are some of the general rules for managing a medical emergency in an ambulatory care setting? • What information from these phone calls should be documented? • What are some of the typical patient emergencies that occur in a healthcare facility? • How should Cheryl instruct a patient to control bleeding from a hemorrhaging wound? • What is the medical office’s responsibility in preparing for community emergencies? • What legal factors should Cheryl keep in mind when handling ambulatory care emergencies? The medical assistant typically is responsible for making the healthcare facility as accident-proof as possible. This requires attention to a number of factors. For example, cupboard doors and drawers must be kept closed; spills must be wiped up immediately; and dropped objects must be picked up. The medical assistant also should make sure that all medications are kept out of sight and away from busy patient areas. If children are in the office, all sharp objects and potentially toxic substances must be kept out of reach. In addition, the medical assistant should never leave a seriously ill patient or a restless, depressed, or unconscious patient unattended. Patient safety is a critical component of the quality of care provided in a healthcare facility. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has conducted extensive research on the features of safe patient environments in physicians’ offices. The DHHS has found the following factors to be crucial to patient safety: Throughout this text, you have learned about situations that could result in serious harm to your patients. You must constantly be on guard to protect patients from possible injury. For example, studies have shown that healthcare workers frequently confuse drug names, which results in administration of the wrong medication; they also fail to identify a patient correctly before performing a procedure and neglect to perform hand sanitization consistently, thus promoting the spread of infectious diseases. The medical assistant is an important link in the delivery of quality and safe care. Can you think of anything you have learned thus far in your studies that could help keep patients safe in the physician’s office? Procedure 36-1 presents a scenario about patient safety. Follow the step-by-step procedure to learn what you can do to protect your patients from possible harm. The healthcare facility should safeguard patients as well as staff members from the possibility of accidental injury. Data compiled by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) reveal that the leading causes of accidents in an office setting are slips, trips, and falls. You must think and work safely to prevent accidents. Following are some suggestions from OSHA for vigilant accident prevention methods (Procedure 36-2): 1. Use proper body mechanics in all situations (see Chapter 32). For example, bend your knees and bring a heavy item close to you before lifting rather than bending from your back; push heavy items rather than pulling them; and ask for assistance when transferring patients. 4. Clean up spills immediately; slippery floors are a danger to everyone. 5. Use a step stool to reach for things, not a chair or a box that could collapse or move. 6. Have handrails available as needed in the facility; use them and encourage patients to use them. 7. Do not overload electrical outlets. A primary concern for personnel and patient safety is infection control. Chapter 27 discussed Standard Precautions in detail and the responsibility of employers to provide appropriate and adequate personal protective equipment (PPE). The goal is to protect staff members from occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens while at the same time safeguarding patients in the facility. OSHA’s guidelines include managing sharps and providing current safety-engineered sharps devices; providing hepatitis B immunization free of charge to all employees at risk of exposure to blood and body fluids; using latex-free supplies as much as possible to prevent allergic reactions in both staff members and patients; identifying all chemicals in the facility with Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS; see Chapter 51) and adequately storing potentially dangerous substances; and performing proper hand hygiene consistently throughout the workday. Another serious concern that faces all of us today is the prevention of workplace violence. Unfortunately, rarely does a week go by without reports of violence in a public place. Employees in a healthcare facility are no exception. We started the text with information about and exercises in communication techniques in the workplace—problem solving, therapeutic communication, and assertive behavior. All of these are helpful in dealing with a difficult patient. Employers should provide training on how to identify potentially violent patients and should discuss safe methods for managing difficult patients. Many employers offer training on how to manage assaultive behaviors. In addition to these concerns, staff members should constantly be on the alert for possible safety hazards in and around the building, such as improper lighting, unlimited access to the facility, and inadequate use of security systems. Procedure 36-3 presents a scenario that deals with employee safety. Follow the steps of this procedure to learn how to handle such a situation. Personal safety guidelines were discussed in Chapter 12. These include numerous work safety practices, such as office security, management of smoke detectors and fire extinguishers, posting of designated fire exit routes, and securing certain items (e.g., narcotics, dangerous chemicals) in locked storage areas in the facility. The medical assistant must be prepared to use a fire extinguisher to prevent injury to patients and to protect the medical facility (Procedure 36-4). An ABC fire extinguisher is effective against the most common causes of fire, including cloth, paper, plastics, rubber, flammable liquids, and electrical fires. Most small extinguishers empty within 15 seconds, so it is important to call 911 immediately if the facility fire is not small and confined. If the fire is small, no heavy smoke is present, and you have easy access to an exit route, use the closest fire extinguisher. However, do not hesitate to evacuate the facility if you believe any danger exists to yourself or to others. Each facility should have a policy and procedure in place for evacuating the building. According to OSHA, the facility’s plan first should identify the situations that might require evacuation, such as a natural disaster or a fire. The following provisions should be included in the facility’s evacuation plan: • Exit doors must be clearly marked, well lit, and wide enough for everyone to evacuate. • Identify hazardous areas in the facility that should be avoided during an emergency evacuation. • Employees should be trained to assist any co-worker or patient with special needs. • A designated individual must check the entire facility, including restrooms, before exiting. He or she must make sure to close all doors when leaving to try to contain the fire or other disaster (Procedure 36-5). Chapter 27 explained the management of biohazardous waste; the use of PPE when the potential exists for exposure to blood and body fluids; the importance of flushing the eyes with an eye wash unit if they are exposed to potentially infectious material; and the consistent use of sharps containers. Regardless of individual responsibilities in the facility, all employees must be aware of potentially dangerous situations and must comply with all safety measures to protect themselves and their patients. OSHA defines regulated waste as any contaminated item that might release blood or other potentially infectious material; contaminated supplies that are caked with dried blood or other potentially infectious material; contaminated sharps; and waste products that contain blood or other potentially infectious material. Healthcare facilities must make special arrangements for the disposal of regulated waste, which often costs as much as 10 times more than regular garbage disposal. It therefore is important to put only supplies contaminated with blood or body fluids into red bag collection systems and sharps containers. Steps for the proper disposal of hazardous materials in the physician’s office include the following: Ambulatory care centers and hospitals may be the first to recognize and initiate a response to a community emergency. If an infectious outbreak is suspected, Standard Precautions should be implemented immediately to control the spread of infection. If the problem has the potential to affect a large number of individuals in the community (e.g., suspected food contamination), a communication network should be established to notify local and state health departments and perhaps federal officials. Your employer may participate in an annual community disaster preparedness drill designed to help facilities improve their response to natural disasters and other emergencies. Local governments are responsible for creating a Local Emergency Management Authority (LEMA) that coordinates police, fire, emergency medical services, public health, and area healthcare response to community-wide emergencies. These agencies are responsible for developing an all-hazards response plan that would be appropriate for any community emergency. Local officials turn to state, regional, or federal officials for assistance as needed. Every healthcare facility should have a policy that includes specific procedures for the management of emergencies on site. When a new employee starts on the job, part of the orientation process is to review the site’s policies and procedures manual. As a new employee, be sure to get answers to any questions you have about emergency management in that particular facility. Staff members should discuss emergencies that may occur and should have an emergency action plan for rapid, systematic intervention. For instance, local industries may present unique problems that call for very specialized care. Plan for these, and ask the physician’s advice on the procedures to follow and the supplies to have on hand. If the facility has several employees, each should be assigned specific duties in the event of an emergency. Organization and planning make the difference between systematic care for patients and complete chaos. Most communities have an emergency medical services (EMS) system. This system includes an efficient communications network (e.g., the emergency telephone number 911), well-trained rescue personnel, properly equipped ambulances, an emergency facility that is open 24 hours a day to provide advanced life support, and a hospital intensive care unit for victims. More than 100 poison control centers in the United States are ready to provide emergency information for the treatment of victims of poisoning. Every healthcare facility is required to post a list of local emergency numbers. This list should be kept in plain sight and should be known to all office personnel. A good place to post this vital information is next to all the phones in the facility. Include on the list the numbers for the local EMS system, poison control center, ambulance and rescue squad, fire department, and police department (Procedure 36-6). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all healthcare facilities be aware of possible agents of bioterrorism, including anthrax, botulism, plague, and smallpox. The physician is responsible for diagnosing and reporting any suspected cases, but the medical assistant may be involved in patient care and certainly will participate in preventing the spread of infection in the facility. As with any suspected infectious disease, Standard Precautions (see Chapter 27) should be used to control disease transmission. These precautions should be implemented with all patients, regardless of their diagnosis or possible infection status. Infection control procedures for bioterrorism threats include the following: • Wear disposable gloves when the potential exists for contamination with blood and body fluids. • Sanitize, disinfect, and sterilize equipment, supplies, and environmental surfaces. • Dispose of contaminated waste in appropriate biohazard containers. Community emergency preparedness plans are required by the federal government so that a coordinated response is in place if a natural disaster occurs, such as Hurricane Katrina, which devastated New Orleans. The federal government requires all healthcare facilities, including private physicians’ offices, to be prepared to provide medical services and to contribute medical supplies if a natural disaster or other emergency occurs in the area. Emergency preparedness plans are designed to coordinate the care provided by all healthcare facilities and agencies in the community, including local emergency management agencies, EMS, fire departments, law enforcement agencies, the American Red Cross, and the National Guard. Each of these groups can provide crucial services during any community emergency. Medical assistants also can contribute to rescue and emergency efforts. Services that might be performed by trained medical assistants include providing emergency first aid at the site of a disaster; conducting patient interviews in an empathetic manner while using therapeutic communication to help calm victims and gather important health-related information; helping with mass vaccination efforts or antibiotic distribution; performing documentation and electronic health record management; ensuring compliance with the procedures required by Standard Precautions; assisting with patient education efforts; and performing phlebotomy and laboratory procedures according to their skill level. First aid is defined as the immediate care given to a person who has been injured or has suddenly taken ill. Knowledge of first aid and related skills often can mean the difference between life and death, temporary and permanent disability, or rapid recovery and long-term hospitalization. The medical assistant may be responsible for initiating first aid in the office and continuing to administer first aid until the physician or the trained medical team arrives. Every medical assistant should successfully complete a course for the professional in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and should continue to hold a current CPR card as long as he or she is employed. Basic knowledge of CPR and life support skills needs to be updated regularly, because procedures change as new techniques are developed. For example, both the American Red Cross and the American Heart Association (AHA) now recommend the inclusion of training on automated external defibrillators for all healthcare workers. Medical assistants need up-to-date training in current emergency practices. They should encourage their local professional chapters to offer workshops on management of emergencies in the ambulatory care setting, as well as community-wide emergency preparedness. Being prepared for both types of emergencies is important. The facility’s employees must be ready to respond both to emergencies on site and to natural disasters or other emergencies that affect the community. Medical assistants are not responsible for diagnosing emergencies, especially over the telephone, but they are expected to make decisions about emergency situations on the basis of their medical knowledge and training. If any doubt exists about how to manage a particular situation or emergency phone call, the medical assistant should not hesitate to consult the physician, the office manager, or some other more experienced member of the healthcare team. Emergency supplies consist of a properly equipped “crash cart” or box of items needed for a variety of emergencies (Figure 36-1). The contents vary to some degree, depending on the types of emergencies the particular office might expect to encounter. Emergency supplies should be kept in an easily accessible place that is known to all personnel in the office, and the supplies should be inventoried regularly. Expiration dates of medications and sterile supplies must be checked weekly or monthly, along with the status of available oxygen tanks and related supplies, and the cart should be replenished with fresh supplies after every use. Emergency pharmaceutical supplies should include certain basic drugs, such as epinephrine, which has multiple uses in emergency situations. As a vasoconstrictor, it controls hemorrhage, relaxes the bronchioles to relieve acute asthma attacks, is administered for an acute anaphylactic reaction, and is an emergency heart stimulant used to treat shock. Epinephrine should be available in a ready-to-use cartridge syringe and needle unit. These units are supplied in 1-mL cartridges. Other drugs used include atropine, digoxin (Lanoxin), nitroglycerin (Nitrostat), and lidocaine (Xylocaine). Atropine reduces secretions, increases respiratory rate and heart rate, and is a smooth muscle relaxant. It is administered in a cardiac emergency for asystole, or it can be used to treat bradycardia. Digoxin is a cardiac drug used to treat arrhythmia and congestive heart failure (CHF); it is good for emergency use because it has a relatively rapid action. Nitroglycerin is a vasodilator that is given to relieve angina; it acts by dilating the coronary arteries so that an increased volume of oxygenated blood can reach the myocardium. Lidocaine is used intravenously to treat a cardiac arrhythmia and locally as an anesthetic, and sodium bicarbonate corrects metabolic acidosis, which typically occurs after cardiac arrest. Emergency medical supplies also should include an emetic, such as syrup of ipecac, which causes vomiting soon after the syrup is swallowed, and activated charcoal, an antidote that is swallowed to absorb ingested poisons. Narcan, an antidote administered intravenously for narcotic drug overdoses, acts to raise blood pressure and increase respiratory rate. Antihistamines for the treatment of allergic reactions and for anaphylaxis need to be available to treat any allergic responses to medications administered in the facility. Such antihistamines include Benadryl for minor reactions and Solu-Medrol, a corticosteroid, for severe anaphylactic reactions. Other medications also may be found on a crash cart. These include isoproterenol (e.g., Isuprel, Medihaler-Iso, Norisodrine), an antispasmodic used to treat bronchospasms (such as those experienced during an asthma attack) that also is effective as a cardiac stimulant; metaraminol (Aramine) (50%, in a prefilled syringe) for severe shock; phenobarbital, amobarbital sodium (Amytal), and diazepam (Valium) for convulsions and/or sedative effects; furosemide (Lasix) for CHF; and glucagon, which is used primarily to counteract severe hypoglycemic reactions (low blood glucose) in diabetic patients taking insulin.

Emergency Preparedness and Assisting with Medical Emergencies

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Safety in the Healthcare Facility

Patient Safety

Employee Safety

Environmental Safety

Disposal of Hazardous Waste

Emergency Preparedness

Community Resources for Emergency Preparedness

Assisting with Medical Emergencies

Emergency Supplies

Emergency Preparedness and Assisting with Medical Emergencies

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access