Emergency Care of the Child

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

![]()

http://evolve.elsevier.com/McKinney/mat-ch/

PEDIATRIC EMERGENCY MEDICATIONS

| MEDICATION | USE |

| Adenosine | Treats supraventricular tachycardia |

| Amiodarone | Treats pulseless arrest, supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia |

| Atropine sulfate | Treats symptomatic bradycardia and toxins/overdose (i.e., organophosphates) |

| Calcium chloride 10% | Treats hypocalcemia, hypermagnesemia, hyperkalemia, and calcium channel blocker overdose |

| Dextrose (25%, 50%) | Treats hypoglycemia, a common complication of dehydration, sepsis, and resuscitation |

| Inotropic agents | Treat hypotension or hypoperfusion, severe congestive heart failure, or cardiovascular shock |

| Epinephrine (1:1000 [endotracheal], 1:10,000 [intravenous/intraosseous]) | Treats bradycardia or pulseless arrest, hypotensive shock, anaphylaxis, toxins/overdose (i.e., beta blockers, calcium channel blockers) |

| Lidocaine | Treats pulseless ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or wide complex tachycardia (with pulses) |

| Magnesium sulfate | Treats torsades de pointes dysrhythmia, hypomagnesemia, or severe asthma |

| Naloxone hydrochloride | Reverses effects of opiate narcotics |

| Sodium bicarbonate (4.2%) | Treats severe metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia, and sodium channel blocker overdose |

Data from Kleinman, M. E., Chameides, L., Schexnayder, S. M., et al. (2010). Part 14: Pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation, 122(Suppl 3), S876-S908.

Very few experiences are as frightening to a family as a child’s sudden illness or injury. Caring for children and families in the emergency setting therefore presents special challenges to the health care team. Nurses play an important role in emergency settings because they are most often responsible for the initial contact, triage, and continuing care throughout an emergency visit. The goals of emergency nursing care include addressing the child’s physical problems, supporting the child’s and family’s coping mechanisms, and creating an atmosphere in which the family is valued and kept as intact as possible.

Growth and Development Issues in Emergency Care

Emergency nursing care of children needs to address both the physiologic and psychological differences in children in terms of age and development. Paying close attention to developmental issues assists in obtaining a more accurate assessment and can affect the course of care (see Chapters 6 through 9 for approaches to children of different ages). The nurse treats each child as an individual and avoids becoming judgmental when a child regresses to a “safer” developmental level. Although children of the same age-group are similar, past experiences, cultural differences, and maturity levels may result in a range of behaviors. One toddler might be much more mature than another, and one adolescent might lean more toward school-age behaviors than another (Box 34-1).

The Infant

An infant experiences the world through the senses; hunger, satiation, cold, warmth, quiet, and noise affect the infant’s comfort or discomfort. An infant has not learned patience and has little tolerance for physical or emotional discomfort, including pain (see Chapter 39 for management of pain in infants and children). Crying can be stressful for caregivers; pacifiers are an adequate self-comforting measure when analgesia is not indicated. Stress can cause increased metabolic demands in the infant so offer rest periods during procedures to maintain normothermia.

Although infants are able to discriminate their parents from others, older infants (9 to 18 months of age, or earlier in some infants) can exhibit signs of both separation and stranger anxiety. The nurse should allow the parent to hold the infant as much as possible for examination and treatment. This may not be possible in a critical situation, but nurses need to remember to reunite parent and child whenever feasible.

The Toddler

Toddlers are just beginning to explore the world and seem to have limitless energy and curiosity. They are also beginning to have a clearer image of themselves as autonomous and distinct beings. For this reason, they do not respond well to restrictions and tend to push any limits imposed. This tendency can be a problem in the emergency setting because some nursing care might involve securing and restraining the toddler, which makes the toddler feel vulnerable. The nurse should be sure to remove any restriction or restraint as soon as safety permits. Toddlers have little understanding of time, so procedures should be introduced just before they are initiated.

The Preschooler

The preschool child is talking and beginning to be more independent. This outward appearance of organization is somewhat misleading, however, because the preschool period is also the stage of fear and fantasy. Because of their imaginative nature, preschoolers need little time lag between the explanation of a procedure and its completion. Additionally, avoid using terms such as “stick” or “cut” to prevent literal misinterpretations of meanings. Preschoolers are strong believers in cause-and-effect relations and tend to blame themselves for illnesses and injuries.

The preschool child may be more willing than the toddler to be separated from parents, but the nurse should keep this separation as brief as possible. The nurse can include the parents in treatments and provide them with instructions on calming the child if they seem unsure. The nurse should not ask a parent to restrain the child because this role may be confusing to the child and difficult for the parent.

The School-Age Child

School-age children are interested in learning and gradually acquire reasoning skills, including some abstract thinking. They are able to understand the cause of illness and injury and are much less likely to fantasize and exaggerate. School-age children have extensive vocabularies, and they can understand simple explanations of procedures. They are also able to make decisions about their own care. By this time, they have developed personal techniques to help them through painful times. The nurse helps them use coping techniques that work for them. Because risk-taking behaviors may begin during this age, caregivers must stress the importance of injury prevention behaviors.

The Adolescent

Although adolescents are at varying stages of puberty, they begin to resemble adults in appearance. They are also beginning to explore the adult world and develop their own unique identities. The nurse needs to remember, however, that even though adolescents may appear physically mature, they might not be emotionally mature, and they continue to require support. Coping with extraordinary changes in their physical appearance, they are often concerned with whether they are “normal” and whether others have similar thoughts and feelings.

Although this is an age of risk taking, which can make them prone to serious injury, adolescents can be quite fearful of death. Although they are aware of the possibility of their own death, they avoid thinking about its reality. Adolescents consider themselves invincible and many experience overwhelming emotions when a friend dies unexpectedly.

Adolescence is an age of extremes—teenagers might either exaggerate or underplay the seriousness of a condition. Sometimes assessing the full extent of an adolescent’s illness or injury is difficult. Expert care of the adolescent requires sensitivity to both verbal and nonverbal cues. Adolescents’ privacy should be respected; nurses should approach them as one would an adult, giving them full attention and respect for their thoughts and feelings.

The Family of a Child in Emergency Care

Stress on the family results directly and indirectly from the child’s illness or injury. The way a child perceives an illness or injury often is related to the parents’ attitude, so caring for the child requires assessment of and intervention with the family.

The most common emotions experienced by parents of children cared for in emergencies are fear and anxiety. Past experiences may lessen or increase these emotions. Parents are afraid of the following possibilities:

Parental guilt is another frequently seen emotion. Parents can feel guilty for the following reasons:

• They feel responsible for their child’s illness or injury.

• They are submitting their child to a painful experience.

• They do not have enough knowledge to make educated decisions about their child’s care.

In addition, parents may have had negative experiences with health care providers in the past or have other concerns about siblings, financial arrangements, and work schedules.

The particular causes of stress for families in emergencies are unique to the circumstances and to the family involved. The nurse needs to define the family (e.g., single parent, two parents, grandparent, other caregiver) and who are the decision makers (e.g., family members, religious leaders) and communicate accordingly. All the stressors combined could stretch parents’ coping mechanisms to the limit and result in anger, withdrawal, or tearfulness. Stress also can manifest itself in hyperactivity—making numerous phone calls, repeating questions, and involving a large number of people.

Including family members in their child’s care can reduce feelings of helplessness and promote positive coping mechanisms. Nurses should facilitate family presence during procedures and encourage them to support their child. Although it is not appropriate to solicit family members to help hold or restrain a child for a procedure, they can offer emotional support. Early assessment and appropriate support before problems occur are advantageous for both health care workers and the family.

Emergency Assessment of Infants and Children

In the emergency setting, assessment of the ill or injured child must be rapid and accurate to identify abnormal findings quickly. In children, initial evidence of life-threatening conditions can be subtle, with few signs of impending respiratory or cardiopulmonary arrest. Making as many initial observations as possible without touching the child is extremely important so that assessments can reflect the child’s baseline, or resting condition. For an apparently stable infant or young child, most of the examination required for general triage can be performed with the child on the parent’s lap. The nurse also observes the relationship between the parents and child during the examination process.

The triage nurse usually performs the initial observation in the emergency setting and decides the level of care needed for the child. Triaging is an important skill that improves with experience. The nurse bases much of the initial assessment on an overall sense of how the child looks—sick or well (an “across the room” assessment). Because children do not try to cover up either how they feel or how they look, the nurse immediately receives a fairly accurate impression of illness or wellness.

Three essential factors combine to form a first impression: respiratory rate and effort, skin color, and response to the environment. Abnormalities are compared with the parent’s or caregiver’s perception (“Is this his normal color?”). If results of this assessment appear to be normal, the nurse completes a more thorough and in-depth evaluation. If the general impression is that the child is seriously ill, the nurse must intervene immediately and combine any additional evaluation with interventions.

Primary Assessment

Primary assessment, which is part of the initial triage assessment, consists of assessing the ABCDEs—airway, breathing, circulation, level of consciousness (disability), and exposure. Because the two most common pathways to death in children are respiratory failure and shock, interventions include providing respiratory and circulatory support. When head, neck, or back trauma is suspected, cervical spine protection should be initiated by maintaining the spine in a neutral position. Cervical and spinal cord injury can be difficult to detect without radiologic intervention in children who cannot effectively verbalize their pain or symptoms.

Airway Assessment

Although determining the cause of respiratory distress or failure in an ill child ultimately will be important, more important is recognizing symptoms and signs of respiratory distress. In the emergency setting, initial treatment is the same regardless of the cause. Remember that apparent respiratory distress can originate from causes such as rib fractures and metabolic acidosis.

Because of some differences in airway anatomy and physiology, children are at greater risk of airway problems than are adults (Table 34-1). When assessing children’s airways, the nurse pays particular attention to breath sounds (often audible to the naked ear) as well as snoring, stridor, wheezing, and grunting. Snoring is caused by obstruction in the upper airway (often the tongue relaxing against the posterior pharynx) and can be heard in a child with decreased mental status. Stridor is a high-pitched sound heard on inspiration (laryngeal obstruction) or on both inspiration and expiration (midtracheal obstruction). Wheezing, a high-pitched, musical sound heard primarily on expiration, signals obstruction of the lower airway. Crackles or rales are fine, popping noises heard on inspiration; they usually indicate fluid in the lungs, such as in pneumonia.

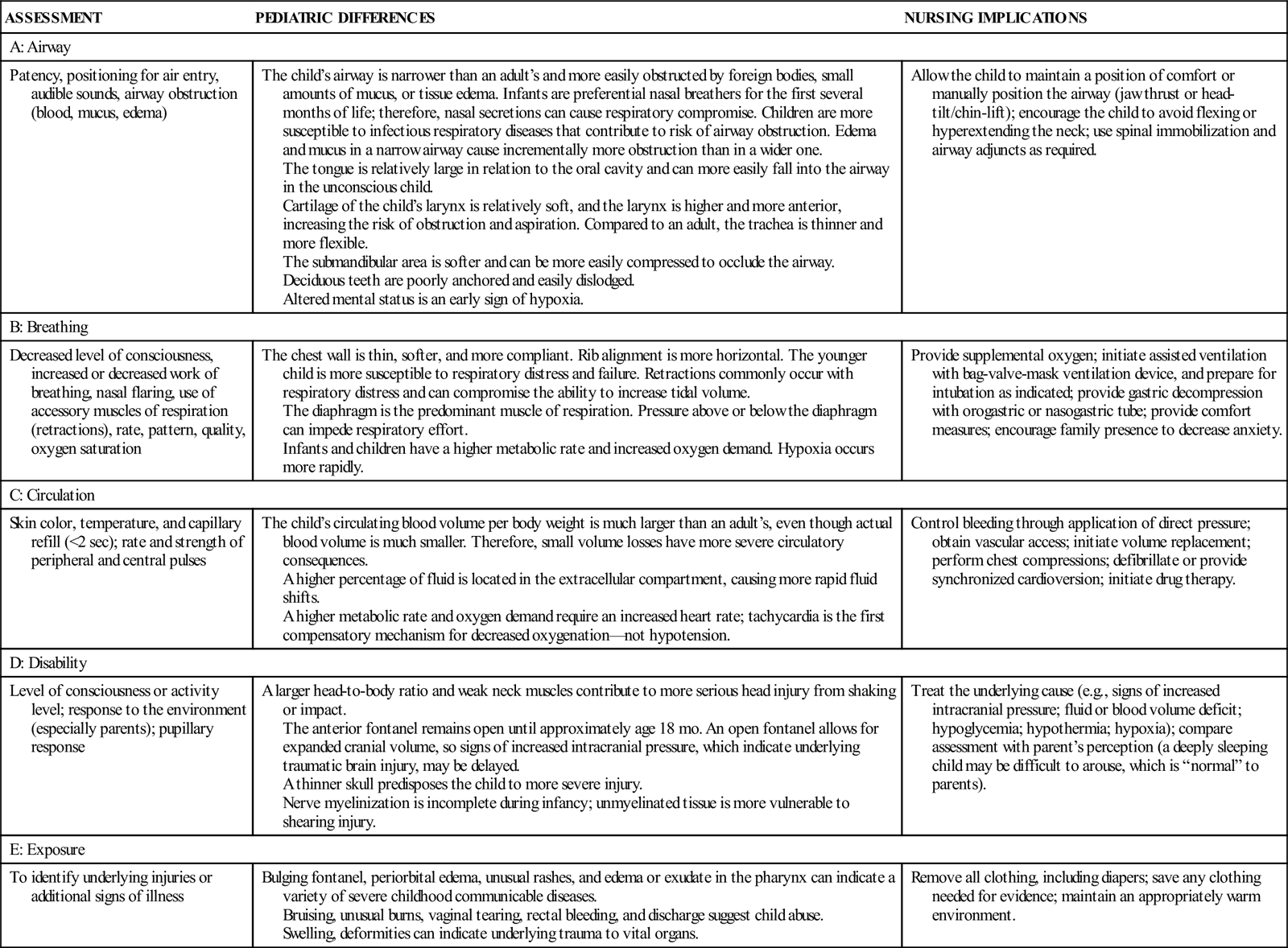

TABLE 34-1

PRIMARY ASSESSMENT IN PEDIATRIC EMERGENCIES

| ASSESSMENT | PEDIATRIC DIFFERENCES | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| A: Airway | ||

| Patency, positioning for air entry, audible sounds, airway obstruction (blood, mucus, edema) | The child’s airway is narrower than an adult’s and more easily obstructed by foreign bodies, small amounts of mucus, or tissue edema. Infants are preferential nasal breathers for the first several months of life; therefore, nasal secretions can cause respiratory compromise. Children are more susceptible to infectious respiratory diseases that contribute to risk of airway obstruction. Edema and mucus in a narrow airway cause incrementally more obstruction than in a wider one. The tongue is relatively large in relation to the oral cavity and can more easily fall into the airway in the unconscious child. Cartilage of the child’s larynx is relatively soft, and the larynx is higher and more anterior, increasing the risk of obstruction and aspiration. Compared to an adult, the trachea is thinner and more flexible. The submandibular area is softer and can be more easily compressed to occlude the airway. Deciduous teeth are poorly anchored and easily dislodged. Altered mental status is an early sign of hypoxia. | Allow the child to maintain a position of comfort or manually position the airway (jaw thrust or head-tilt/chin-lift); encourage the child to avoid flexing or hyperextending the neck; use spinal immobilization and airway adjuncts as required. |

| B: Breathing | ||

| Decreased level of consciousness, increased or decreased work of breathing, nasal flaring, use of accessory muscles of respiration (retractions), rate, pattern, quality, oxygen saturation | The chest wall is thin, softer, and more compliant. Rib alignment is more horizontal. The younger child is more susceptible to respiratory distress and failure. Retractions commonly occur with respiratory distress and can compromise the ability to increase tidal volume. The diaphragm is the predominant muscle of respiration. Pressure above or below the diaphragm can impede respiratory effort. Infants and children have a higher metabolic rate and increased oxygen demand. Hypoxia occurs more rapidly. | Provide supplemental oxygen; initiate assisted ventilation with bag-valve-mask ventilation device, and prepare for intubation as indicated; provide gastric decompression with orogastric or nasogastric tube; provide comfort measures; encourage family presence to decrease anxiety. |

| C: Circulation | ||

| Skin color, temperature, and capillary refill (<2 sec); rate and strength of peripheral and central pulses | The child’s circulating blood volume per body weight is much larger than an adult’s, even though actual blood volume is much smaller. Therefore, small volume losses have more severe circulatory consequences. A higher percentage of fluid is located in the extracellular compartment, causing more rapid fluid shifts. A higher metabolic rate and oxygen demand require an increased heart rate; tachycardia is the first compensatory mechanism for decreased oxygenation—not hypotension. | Control bleeding through application of direct pressure; obtain vascular access; initiate volume replacement; perform chest compressions; defibrillate or provide synchronized cardioversion; initiate drug therapy. |

| D: Disability | ||

| Level of consciousness or activity level; response to the environment (especially parents); pupillary response | A larger head-to-body ratio and weak neck muscles contribute to more serious head injury from shaking or impact. The anterior fontanel remains open until approximately age 18 mo. An open fontanel allows for expanded cranial volume, so signs of increased intracranial pressure, which indicate underlying traumatic brain injury, may be delayed. A thinner skull predisposes the child to more severe injury. Nerve myelinization is incomplete during infancy; unmyelinated tissue is more vulnerable to shearing injury. | Treat the underlying cause (e.g., signs of increased intracranial pressure; fluid or blood volume deficit; hypoglycemia; hypothermia; hypoxia); compare assessment with parent’s perception (a deeply sleeping child may be difficult to arouse, which is “normal” to parents). |

| E: Exposure | ||

| To identify underlying injuries or additional signs of illness | Bulging fontanel, periorbital edema, unusual rashes, and edema or exudate in the pharynx can indicate a variety of severe childhood communicable diseases. Bruising, unusual burns, vaginal tearing, rectal bleeding, and discharge suggest child abuse. Swelling, deformities can indicate underlying trauma to vital organs. | Remove all clothing, including diapers; save any clothing needed for evidence; maintain an appropriately warm environment. |

Data from Emergency Nurses Association. (2007). Trauma nursing core course provider manual (6th ed.). Des Plaines, IL: Author.

Breathing Assessment

Level of consciousness, rate and depth of breathing, breath sounds, and the child’s respiratory effort are indicative of relative oxygenation. Anxiety or decreased responsiveness may denote hypoxia. A rapid respiratory rate with shallow breathing indicates respiratory distress. Very slow breathing in an ill child is an ominous sign, indicating respiratory failure. A slowly breathing child might no longer have the energy for adequate ventilation. Increased work of breathing with quiet breath sounds may indicate an absence of air entry into lung fields. Abdominal breathing is normal in the infant or young child, so the nurse observes the rise and fall of the abdomen instead of the chest.

The use of accessory muscles for breathing invariably indicates respiratory distress. The child’s chest wall is relatively weak and unstable, so retractions occur with increased work of breathing. Assessment of breathing includes observing the child for intercostal, substernal, suprasternal, supraclavicular, and infraclavicular retractions. As a child becomes exhausted, retractions may diminish, usually indicating respiratory failure. Nasal flaring with inspiration is another form of accessory muscle use. Grunting, a sound made by the expiration of air against partially closed vocal cords, is a sign of hypoxemia and represents the body’s effort to improve oxygenation by generating positive end-expiratory pressure.

The nurse observes the child’s preferred body posture. A child in respiratory distress is upright with the jaw thrust forward, leaning forward on outstretched arms—the tripod position. This position, often referred to as “tripoding,” helps maximize airway opening and the use of accessory muscles of respiration.

Once the work of breathing has been carefully observed, listening to the chest provides some useful information. Children have small chests, and breath sounds can be transmitted throughout the chest. The nurse therefore auscultates a child’s chest at both sides of the body at the midaxillary line and over the trachea to confirm equality of breath sounds and distinguish upper from lower airway noises.

Normal respiratory rates for children vary by age and are faster than for adults (see Table 33-1). A respiratory rate greater than 60 breaths per minute, however, is abnormal for any age. Another important adjunct for respiratory assessment is the pulse oximetry reading (see Chapter 37). Measuring exhaled carbon dioxide (CO2) using capnography (even in nonintubated patients) may provide a more sensitive detection of hypoventilation, impaired gas exchange and perfusion, metabolic acidosis, and carbon monoxide poisoning (“Is Capnography Used,” 2011; “Monitoring ETCO2,” 2011).

Cardiovascular Assessment

Cardiovascular assessment includes observing the child’s skin color and temperature, checking capillary refill, and assessing central and peripheral pulse rate and quality. A child can compensate more effectively for fluid loss, through increased heart rate and peripheral vasoconstriction, than an adult can. Tachycardia and decreased peripheral perfusion are early signs of cardiovascular compromise in a child and require immediate intervention to prevent decompensation. Hypotension is a late finding in a child with shock. Hypotension manifests only after significant fluid loss because of the compensatory mechanisms that result in vasoconstriction (Kleinman, Chameides, Schexnayder, et al., 2010). Hypotension in children suggests that compensatory mechanisms are no longer adequate to maintain cardiac output.

Disability: Neurologic Assessment

The infant’s or child’s level of consciousness is an essential component of the primary assessment. Alteration in level of consciousness (irritability or agitation, lethargy, or inability to recognize parents or caregivers) can be the first sign of respiratory compromise or worsening condition.

A rapid neurologic assessment consists of two components: (1) pupillary reactivity and size; and (2) a brief mental status assessment (AVPU: alert, responds to voice, responds to pain, unresponsive). More thorough and sophisticated means of assessment are used later if needed (see Chapter 52). Serial assessment is imperative. Progressive loss of consciousness may be a result of hypoxemia, hypoglycemia, increased intracranial pressure, or another life-threatening condition.

Exposure

Primary assessment ends with exposure, or removing the child’s clothing to identify additional injuries or indicators of illness. The nurse needs to preserve the child’s clothing appropriately if it will be needed for evidence in any potential civil or criminal proceeding. Infants and children have a larger body surface area-to-weight ratio, making them at higher risk for hypothermia. Maintaining body temperature by shivering increases metabolic needs, such as oxygen and glucose, and the child has limited reserves. The risk of hypoxia and hypoglycemia is higher in neonates from utilization of brown fat for nonshivering thermogenesis and an increased metabolic demand secondary to an infectious or physiologic process. Methods to help the child maintain a normothermic state or help with warming include overhead warmers and heat lamps, warmed intravenous (IV) fluids and humidified oxygen, removal of wet clothes, and providing warmed blankets.

Secondary Assessment

After the primary assessment is complete and interventions (if necessary) have stabilized the child, the nurse begins the secondary assessment. Components of the secondary assessment include vital signs, assessing for pain, history and head-to-toe assessment, and inspection (Table 34-2).

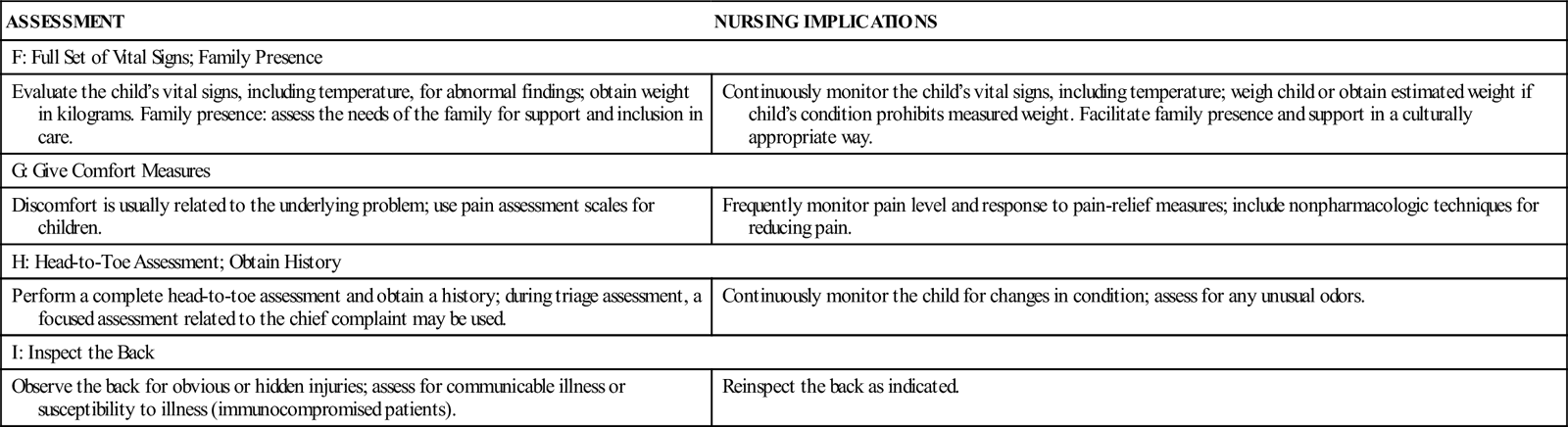

TABLE 34-2

SECONDARY ASSESSMENT IN PEDIATRIC EMERGENCIES

| ASSESSMENT | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| F: Full Set of Vital Signs; Family Presence | |

| Evaluate the child’s vital signs, including temperature, for abnormal findings; obtain weight in kilograms. Family presence: assess the needs of the family for support and inclusion in care. | Continuously monitor the child’s vital signs, including temperature; weigh child or obtain estimated weight if child’s condition prohibits measured weight. Facilitate family presence and support in a culturally appropriate way. |

| G: Give Comfort Measures | |

| Discomfort is usually related to the underlying problem; use pain assessment scales for children. | Frequently monitor pain level and response to pain-relief measures; include nonpharmacologic techniques for reducing pain. |

| H: Head-to-Toe Assessment; Obtain History | |

| Perform a complete head-to-toe assessment and obtain a history; during triage assessment, a focused assessment related to the chief complaint may be used. | Continuously monitor the child for changes in condition; assess for any unusual odors. |

| I: Inspect the Back | |

| Observe the back for obvious or hidden injuries; assess for communicable illness or susceptibility to illness (immunocompromised patients). | Reinspect the back as indicated. |

Data from Emergency Nurses Association. (2007). Trauma nursing core course provider manual (6th ed.). Des Plaines, IL: Author.

Vital Signs

Vital signs are useful in the triage assessment of the child, but because age variations make their significance more difficult to interpret, they are not as reliable an indicator as in adult assessment. This variation is especially applicable to temperature. For example, an infant has an immature thermoregulatory system and may not have a fever or may even be hypothermic in the presence of infection, so the nurse needs to be alert for supporting signs. The nurse remembers that an alteration in one part of the vital signs may result in abnormal values in other parts. For example, an abnormally high heart rate and respiratory rate may be a result of hyperthermia, crying, pain, hypoxemia, or hypovolemia (see Chapter 37 for methods of obtaining a temperature).

When taking a child’s vital signs, the nurse observes the respiratory rate first and then obtains the pulse; the nurse obtains the temperature and blood pressure last because these procedures can be more upsetting for children. The nurse should be certain to use the correct size blood pressure cuff and take both the respiratory and heart rates for 1 full minute because subtle differences are important in the child. Normal pediatric respiratory and heart rates are faster than adult rates, whereas the blood pressure is lower on average (see Table 33-1 and http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/child_tbl.pdf). An accurate weight should be obtained at this time, and monitors, such as a cardiac or a pulse oximeter, should be applied as indicated.

History and Head-to-Toe Assessment

A brief history provides information about prior illness or injury that might affect the emergency care of the child. One format often used for pediatric patients is the mnemonic SAMPLE:

This mnemonic gives sufficient information to determine whether the child’s medical history will play an important role in assessment and treatment of the current illness or injury. In emergency departments that care for children, a list of immunizations and the appropriate ages should be posted in a convenient location (see http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules/child-schedule.htm).

After obtaining an appropriate history, the nurse begins to perform a head-to-toe assessment, documenting any findings that might affect the child’s condition. Assessment findings are compared with the history to aid in diagnosis and look for inconsistencies. The nurse inspects all body surfaces, looking for fractures, lacerations, contusions, and penetrating injuries. The nurse also observes the skin for petechiae or rashes. The presence and pattern of any pain are described. The nurse pays particular attention to signs of pneumothorax or hemothorax (e.g., decreased breath sounds on the affected side, signs of hypoxemia, and signs of shock). The nurse then palpates the child’s abdomen and auscultates for the presence of bowel sounds. Any sign of hematuria suggests genitourinary injury or infection. Blood found at the urinary meatus suggests disruptive injury of the lower urinary tract, and a urinary catheter should not be inserted.

Diagnostic Tests

Once the child has arrived in the emergency setting and has undergone initial assessment and interventions, diagnostic tests are performed that assist in the evaluation process. Standard protocols for laboratory tests usually include a complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, serum electrolytes, glucose (checked at the bedside), and urinalysis. Additional studies may be necessary for the child who has multiple trauma including laboratory tests for coagulation profiles, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, glucose, amylase, lipase, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT, also known as aspartate aminotransferase [AST]), serum glutamic-pyruvate transaminase (SGPT, also known as alanine aminotransferase [ALT]), and blood type and crossmatch.

Radiologic films may be obtained depending on the presenting problem and assessment data. Placement of a gastric tube, urinary catheter, or other device may be required. Orogastric tubes should be placed in children with suspected head trauma because of the risk of misplacement and injury with a nasogastric tube in children with basilar skull and facial fractures. Gastric tubes are placed to reduce gastric inflation that can place pressure on the diaphragm and decrease ventilation effectiveness because children are diaphragmatic breathers (Kleinman et al., 2010).

Weight

Determining the child’s weight is essential in emergency care because all medication dosages and fluid amounts are calculated according to the child’s weight in kilograms. The nurse weighs the child on an appropriately calibrated scale if possible, following agency procedure for measuring and recording weight (e.g., with or without clothing, diaper on vs. diaper off).

Another way to determine the child’s weight and medication dosages is through the use of a length-based resuscitation tape, such as the Broselow tape. Tapes with precalculated medication doses calculated at various lengths have been proven more accurate in the prediction of body weight than provider or parent estimate-based methods (Kleinman et al., 2010). A length-based resuscitation tape is placed on a gurney or stretcher next to the child, and the child’s length is measured. The length is keyed to emergency medication dosages, usually listed on the tape. The tape also indicates fluid bolus volumes, defibrillation energy levels, and sizes of the pediatric airway, bag-valve-mask ventilation device, laryngoscope, endotracheal tube, gastric tube, urinary catheter, chest tube, and IV catheter. The validity of length-based resuscitation tapes is questioned with the growing trends in childhood obesity, and these tapes should be used with caution in overweight children.

Parent-Child Relationship

Rapid triage assessment of the child also includes observation of the child in relation to the parents. If the relationship does not appear to be close, comfortable, and trusting, the nurse may want to explore this further.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation of the Child

Airway and Breathing

Initial Assessment and Intervention

Whereas lethal arrhythmias related to heart disease are the most common causes of cardiopulmonary arrest in adults, factors leading to shock and respiratory failure are the most common causes of cardiopulmonary arrest in children. Early recognition of and intervention for respiratory distress and compensated shock can be lifesaving for the child. Assistance with ventilation and administration of fluids may prevent further deterioration in the child’s condition. Once the child progresses to respiratory failure and shock, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is necessary. Resuscitation of children requires attention to the differences between adults and children (see Table 34-1).

If a child is unresponsive and not breathing, basic life-support measures will be initiated. However, the child with spontaneous respiratory effort or a pulse will require more evaluation to determine the need for CPR. Cardiac arrests in infants and children are more commonly caused by asphyxiation, and although research has shown that resuscitation outcomes are better with a combination of ventilations and chest compressions, it is unknown whether the sequence makes a difference (Berg, Schexnayder, Chameides, et al., 2010). To avoid delays in initiating CPR, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends the CAB sequence (circulation, airway, breathing) beginning with 30 chest compressions followed by opening the airway and 2 rescue breaths (Berg et al., 2010). The early initiation of high-quality chest compressions improves blood flow to vital organs and will improve the chances of survival (Kleinman et al., 2010).

Because of the proportionately larger size of the child’s head with a weaker supporting muscle structure, repositioning the head and placing a rolled-up towel under the child’s shoulders can often facilitate improved air exchange. Additionally, the tongue of the young child is larger in relation to the oropharynx and is often the cause of airway obstruction. When administering assisted ventilations, the nurse should stop inflating the lungs when the chest just begins to rise and allow enough time for exhalation (longer than inhalation). Endotracheal intubation by a provider skilled in the technique is necessary if the child cannot be ventilated adequately with these measures or if prolonged ventilation is anticipated. Ventilations should be given at a rate of 12 to 20 per minute or approximately 1 breath every 3 to 5 seconds; each breath should be given over 1 second (Berg et al., 2010).

A pressure gauge attached to the bag-valve-mask ventilation device helps deliver breaths at the correct pressure, especially for infants and young children. Choosing the appropriate-size mask and the correct volume bag is important. The mask should cover the child’s mouth and nose but not place pressure on the eyes. A good fit ensures a seal around the face and under the chin. Gastric decompression by use of an orogastric or nasogastric tube is indicated during assisted ventilation.

Obstructed Airway Management

Inability to inflate the lungs suggests airway obstruction, a life-threatening emergency. When ventilation is not possible, the infant or child will die in a very short time.

Management of airway obstruction depends on the cause and on the child’s age. Definitive treatment depends on diagnosis. Whereas adults more commonly choke while eating, children can choke while eating or playing. Foreign body aspiration, for example, is a problem frequently seen in young children, with a large number of aspirations attributed to coins, small toy parts, and certain foods, particularly candy, nuts, and grapes. More than 90% of pediatric deaths related to choking occur in children younger than 5 years of age (Berg et al., 2010). When a child is unable to ventilate adequately and aspiration of a foreign body is suspected as the cause, the nurse initiates maneuvers to remove the obstruction.

Although controversy remains about how to clear a foreign body from the airway, for conscious children older than 1 year, the AHA recommends using the Heimlich maneuver. CPR should be initiated for all unresponsive infants and children with a foreign body aspiration. The rescuer tries to visualize the foreign body for removal before each ventilation sequence (Berg et al., 2010). Removal of a foreign body from an infant involves placing the infant in a downward slant position and giving five back blows alternating with five chest compressions. Abdominal thrusts are not used in infants because of the risk of liver injury. Blind finger sweeps used in an attempt to remove a possible foreign object are not recommended because of the risk of forcing the object farther down the airway or causing injury to the supraglottic area. If an object is seen, it should be removed.

If obstruction continues after these maneuvers, subsequent actions may include direct laryngoscopy and use of a Magill forceps to remove the foreign body. Tracheostomy is used as a last resort. When the lower airway is obstructed because of a disease process, such as asthma, medication to open the airway may be necessary.

Circulation

The nurse feels for the pulse in the child older than 1 year by palpating the carotid or femoral artery and looking for signs of circulation such as movement. For an infant younger than 1 year, the nurse uses the brachial artery because the infant’s relatively short, thick neck makes palpation of the carotid artery difficult. The nurse begins chest compressions if no pulse is palpated after approximately 10 seconds, or if the infant’s or child’s heart rate is less than 60 beats per minute (bpm) and perfusion is poor. Compressions should be administered at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute with enough pressure to depress at least one third of the chest and allowing complete recoil after each compression (Berg et al., 2010) (Table 34-3).

TABLE 34-3

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONAL BASIC LIFE SUPPORT ELEMENTS FOR INFANTS AND CHILDREN

| ELEMENT | INFANT (<1 YEAR) | CHILD (1 YEAR-ONSET OF PUBERTY) | ADULT (ADOLESCENT) |

| Discovery | Unresponsive No breathing or only gasping | ||

| No brachial pulse palpated in 10 sec | No carotid or femoral pulse palpated in 10 sec | No carotid pulse palpated in 10 sec | |

| Sequence for CPR = C-A-B Circulation-Airway-Breathing | |||

| Circulation Compressions | At least 100 compressions/min “Push fast” “Push hard” | ||

| Location | Compress just below nipple line | Use automatic external defibrillator (AEDCompress in center of chest between nipples | |

| Technique | Two fingers, or two thumbs encircling hands around chest with two rescuers | Heel of one or two hands-stacked | Heel of two hands-stacked |

| Depth | About 1.5 in (4 cm) | About 2 in (5 cm) | At least 2 in (5 cm) |

| Ratio | 30:2 one rescuer; 15:2 two rescuers | 30:2 one rescuer; 15:2 two rescuers | 30:2 one rescuer or two rescuers |

| Compressions/ Ventilations | Allow chest to fully recoil after each compression Limit interruptions in compressions to under 10 seconds | ||

| Airway | Head-tilt/chin-lift (if trauma is present, use jaw thrust) | ||

| Breathing Advanced airway in place | 8 to 10 breaths/min; not correlated with chest compressions 1 breath every 6 to 8 sec 1 sec for each breath; look for chest to rise | ||

| Defibrillation | Defibrillate as soon as possible; use manual defibrillator or AED with pediatric dose attenuator | Defibrillate soon as possible; use automatic external defibrillator (AED) | |

| Foreign body airway obstruction | Back blows, chest compressions | Heimlich maneuver (abdominal thrusts) | |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree