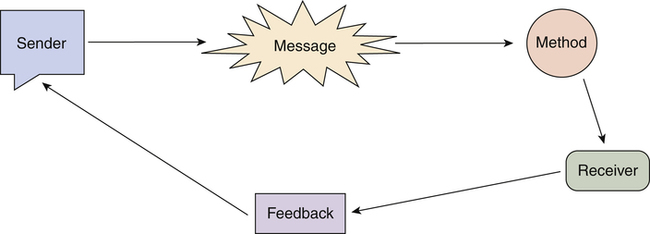

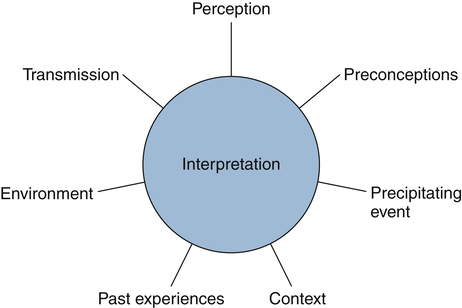

Anna Marie Sallee, PhD, MSN, RN After studying this chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Outline factors that can influence the communication process. 2. Communicate effectively with diverse intergenerational and interdisciplinary team members. 3. Apply positive communication techniques in diverse situations. 4. Recognize negative communication techniques. 5. Evaluate conflicting verbal and nonverbal communication cues. 6. Examine constructive methods of communicating in conflict situations. 7. Respond to inappropriate use of logical fallacies in communication. A participatory form of communication that promotes change. The process of hearing what others are saying with a sense of seriousness and discrimination. A manner of communicating that limits the focus on or understanding of the opinions, values, or beliefs of others. A form of communication that enables a person to act in his or her own best interest without denying or infringing upon the rights of others. Obstructing communication through noncommittal answers, generalization, or other techniques that hamper continued interaction. A process of relaying information between or among people by the use of words, letters, symbols, or body language. An experience in which there is simultaneous arousal of two or more incompatible motives. A process whereby the receiver takes the message and interprets its meaning. An attempt to experience another person’s point of view without losing one’s own identity. A process of translating an idea already conceived into a message suitable for transmission. An attitude that relays acceptance and approval of another person. Response from the receiver, which can be verbal or nonverbal. Unconscious exclusion of extraneous stimuli. The data that is meaningful and alters the receiver’s understanding. Receiver’s understanding of the meaning of the communication. Negative communication techniques Behaviors that block or impair effective communication. Communicating in a timid and reserved manner resulting in limited concern for one’s own rights regardless of the situation. Unspoken cues (intentional or unintentional) from the communicant, such as body positioning, facial expression, or lack of attention. An attitude of willingness to self-disclose, react honestly to the messages of others, and own one’s feelings and thoughts. A form of communication in which the individual fails to say what is meant. The manner in which one sees reality. Positive communication techniques Behaviors that enhance effective communication. The destination for or receptor of a message. Anyone who wishes to convey an idea or concept to others, to seek information, or to express a thought or emotion. The concern that is fostered by being descriptive rather than evaluative and provisional rather than certain. Additional resources are available online at: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cherry/ Vignette Stacy calls the ED secretary to arrange for the transfer to occur in 20 minutes. To her surprise, she finds out that the patient has left the department and is being brought to 4-East immediately. Within a few moments, the patient and ED nurse arrive. The ED nurse states that he wants to give report on this patient quickly because he needs to return to the ED right away. Stacy assists him in transferring the patient to a bed and making the patient as comfortable as possible. Within 10 minutes Stacy receives a telephone call from the ED charge nurse wanting to discuss this incident. Negative comments are made about the 4-E nurse who left the unit “unannounced” and that “there is a concern for patient safety.” How can Stacy best facilitate a positive outcome in this situation? Questions To Consider While Reading This Chapter: 1. What communication strategies should Stacy use to respond to the accusations being made by the ED charge nurse and to help resolve the conflict? 2. What strategies can Stacy use to build a trusting relationship between her and the ED charge nurse? 3. What positive communication techniques could have prevented this situation from occurring? 4. What nonverbal cues might Stacy have observed between the two nurses during the report exchange? 6. What strategies can Stacy implement to increase the communication skills of her staff? Effective communication is a foundational component of professional nursing practice. The development of effective communication skills can only enhance each nurse’s professional image while building strong relationships with both patients and colleagues. Understanding communication processes and principles is required for nurses to interact professionally with patients, families and significant others, nursing peers, managers, student nurses, physicians, other members of the interdisciplinary team, and the public. Nurses communicate through a variety of media including the spoken and written word, demonstration, role modeling, and on occasion, public appearances. The exchange of ideas and feelings is hardly limited to verbal communication. There are many types of nonverbal communication that are often as meaningful as, and in many instances more meaningful than, audible expression. Because communication is such a complex process, there are infinite opportunities for sending or receiving incorrect messages. All too frequently communication is faulty, resulting in misperceptions and misunderstandings. Communication is a process requiring certain components. There must be a sender, a receiver, and a message. Effective communication is a dynamic process: with a response (feedback), the sender becomes the receiver, the receiver becomes the sender, and the message changes (Figure 18-1). The method of delivery influences the effectiveness of communication. In addition, communication is affected by many subcomponents, both environmental and in the mind of the communicators (Figure 18-2). When communication with another person occurs, verbally or nonverbally, a typical pattern develops that includes the actual message being sent, the receiver’s belief or interpretation of that message, and the reaction to the message. Interpretation of information can be influenced by such factors as context, environment, precipitating event, preconceived ideas, personal perceptions, style of transmission, and past experiences. Because of the interaction of these factors, the sender’s message may mean to the receiver something that was entirely unplanned or unexpected by the sender (see Fig. 18-2). Feedback, simply put, is the response from the receiver. However, as with all communication, feedback is a dynamic process. As the receiver interprets and responds to the original message, the sender begins the same process of feedback to the receiver. Because of this circular property, the process frequently is referred to as the feedback loop (van Servellen, 1997). As with the original message, feedback is not confined to verbal responses alone. Both communicants constantly assess nonverbal communication as well. Feedback is formed based on all the components of interpretation and filtration. Verbal communication is the most common form of interpersonal communication and involves talking and listening. An important clue to verbal communication is the tone or inflection with which the words are spoken and the general attitude used when speaking. Suzette Haden Elgin refers to the “tune the words are set to” (1993, p. 186). The key to the true meaning of a statement may be contained in the emphasis placed on a specific word. Consider how differently the following phrase could be perceived based on the inflection or the emphasis on the wording: An important concept to remember is that when the verbal message and the nonverbal message do not agree, the receiver is more likely to believe the nonverbal message. In 1971, Albert Mehrabian (1981) conducted a seminal study on nonverbal communication in which he found that most communication is 55% nonverbal, 38% vocal signals (such as tone, pitch, or pace), and only 7% the actual words we say. Mehrabian’s study has significantly influenced our understanding of the “silent messages” we send. In fact, body language is often the most trusted indicator for conveying feelings, attitudes, and emotions (Borg, 2011) because it so often comes from our subconscious—which is much less likely to deceive! Nonverbal language includes such things as dress, posture, facial expression, eye contact, body movements, body tension, spatial distance, touch, and voice. Kim Holland (2012) states eloquently: “Patients see our hearts through our eyes. It takes an incredible amount of professionalism to appear relaxed, make eye contact and help our patient know—for that brief moment—we are with them.” Body positioning toward the patient, a relaxed stance, a gentle touch, and an open face will signal your total presence. Blocking occurs when the nurse responds with noncommittal or generalized answers. For example: Makayla: “What makes you think you might not wake up, Mr. Clayton?” Makayla: “What kind of surgery did he have?” Makayla: “It sounds like his condition was critical going into surgery.” Mr. Clayton: “Yes, ma’am. He’d been sick for a long time.”

Effective Communication and Conflict Resolution

Chapter Overview

The Communication Process

Interpretation

Feedback

Verbal Versus Nonverbal Communication

Verbal Communication

Nonverbal Communication

Positive Communication Techniques

Negative Communication Techniques

Blocking

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access