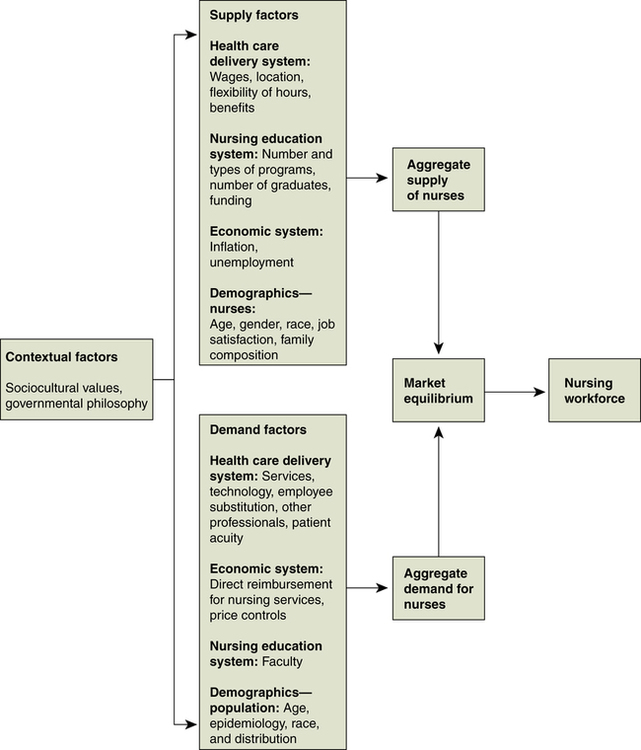

Mattia J. Gilmartin, RN, MBA, PhD At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe how the economic concepts of supply, demand, complements and substitutes, competition, and market failure apply to nursing and health care. • Define and differentiate methods of cost evaluation. • Discuss how the cost of care and quality of care are related. • Compare and contrast the economic foundations of emerging models for health system reform. Health care professionals historically have been largely unaware of the economic costs and consequences of their clinical decisions. This is due, in part, to the nature of health care financing and the separation of clinical and management functions within health care organizations. However, the spiraling cost of health care as a portion of the nation’s overall economy and the inefficient distribution and use of scarce resources within the health care sector (Goodell & Ginsburg, 2008; Institute of Medicine, 1999) underscore the need for health care professionals to understand and incorporate economic principles in their clinical and management decision making. As the largest professional group in the health care workforce (Hager, Tise, Kuta, Spencer, & Fritz, 2006), nurses are in a unique position to influence the efficient and effective use of scarce health care resources. More broadly, an understanding of economic principles and the tools of economic evaluation enables nurses to demonstrate the contributions of nursing practice that improve resource use in the production of health care services. Nurses involved in clinical practice, administration, education, policy making, and research can use principles of economics to: • Provide nursing care in the least costly manner • Protect the scope of nursing practice by demonstrating the quality and value of nursing services in relation to other professionals • Develop opportunities to expand settings for nursing practice by demonstrating the cost and quality of nursing interventions • Understand what purchasers and consumers want from nursing and take steps to satisfy these needs and demands • Promote health system change to expand access, improve the quality, and ensure more equitable distribution of health care resources • Integrate nursing-specific quality measurement systems and concepts into larger organizational quality improvement initiatives that are largely controlled by nonnurses (Bolton, Donaldson, Rutledge, Bennett, & Brown, 2006; Buerhaus, 1992) Economics is the study of the distribution of resources across a population. Health economics is the study of the production and distribution of health care resources and their impact on a population. Health care resources consist of medical supplies, such as pharmaceutical goods, latex gloves, and bed linens; personnel, including nurses, physicians, and other allied health professionals; and capital inputs, including hospitals and nursing home facilities, diagnostic and therapeutic equipment, and other items used to provide medical care (Santerre & Neun, 2004). Health care resources are scarce; that is, there is a limit to the quantity that can be produced at a given time, although the demand for these resources can be limitless. Therefore economists are interested in how society makes important decisions regarding the consumption, production, and distribution of these goods and services within the health care sector and in relation to other societal needs such as education, housing, and defense. As social scientists, health economists seek to answer four basic questions (Santerre & Neun, 2004): Although economic theory is complex, it is guided by a relatively small set of principles and concepts. These concepts are presented in Box 7-1 and provide the foundation for a more detailed explanation of how economic principles underpin current health care issues discussed in this chapter (Henderson, 2008). Typically, economists assume certain conditions to understand human behavior in relation to the production and distribution of resources. Unlike other industries, the health care sector violates a number of assumptions that support general economic theory (Rice, 1998). The need for health care services is irregular and cannot be predicted by either consumers or providers (Arrow, 1963). Consumers who demand health care cannot predict when illness or catastrophe will strike, and health care providers cannot forecast the costs of the treatment(s) required. Health care professionals who provide medical interventions also face uncertainty regarding when patients will present themselves for treatment, as well as the extent to which patients will respond to prescribed treatment regimens. The unexpected and often costly nature of illness gives rise to the purchase of insurance as a safeguard against the cost of medical treatment in the event of illness (Folland, Goodman, & Stano, 2007). Consumers buy insurance to guard against the risk and uncertainty of illness. Insurance introduces an intermediary between the consumer (person requiring medical care) and the providers of care (health care professionals and organizations). Consumers do not pay the full price for their medical care and are separated from making decisions about medical services based on the price of those services. In economic theory, price is the key measure used to determine what a consumer is willing to pay for a good or service and enables an organization to gauge its output in relation to consumer desires and buying behaviors. Insurance also changes the demand for care, and it potentially changes the incentives for providers to offer certain types of treatments that are reimbursed by insurance (Johnson-Lans, 2006). Economic theory assumes that buyers and sellers have equal information about the cost, price, and quality of goods and services. However, in health care markets, professionals (the sellers) typically have more information about treatment options than do clients (the buyers). In some instances, information is unknown to both the professional and the individual. For example, when a person has cancer that has not yet been detected by regular screenings, a treatment course cannot be formulated because neither party knows that medical services are needed. The lack of symmetrical information is a problem, because it distorts the basic mechanism of consumer sovereignty, in which consumers (clients) dictate what goods and services are produced because they know what they want and what they are willing to pay (Folland, Goodman, & Stano, 2007). Economists assume that organizations seek to maximize profits and that models of firm behavior explain how businesses allocate resources to increase profits. It is important to note that all businesses must take in more money than they spend (make a profit or surplus) for continued operations. Many health care providers—including hospitals, nursing homes, and insurance companies—are operated as not-for-profits. Approximately 3000 of the nation’s 5700 registered hospitals are organized as privately owned not-for-profit organizations (American Hospital Association, 2008). Not-for-profit is simply a tax designation, in which property and earnings are not subject to tax. Competition is a force that produces the most efficient allocation of resources because owners must use their resources to produce the highest satisfaction for society. Economists assume that markets are perfectly competitive, consisting of numerous buyers and sellers, with no power over price, who have complete information and can enter and exit the market freely by selling similar goods or services. Health care markets violate several of these assumptions. As described previously, health care markets are characterized by asymmetrical information and have weak pricing mechanisms because of third-party payment in the form of insurance. In addition, market entry is blocked by licensure for professional practice, advertising restrictions, and ethical standards that prevent providers from competing with one another. Because health care is considered to be a public good, organizations in the sector are subjected to regulation by state and federal government, as well as other outside entities, to ensure the quality of care and distribution of resources across geographic areas (Hoffman, Klees, & Curtis, 2007). Economics is concerned with the distribution of scarce resources so that society receives the highest possible satisfaction from the combination of goods and services produced from these resources. Distributive justice, or equity, is the extent to which resources are allocated in a fair and equal manner to everyone involved. In pure market economies, the price mechanism is used to strike a balance (equilibrium) between the prices that suppliers charge and the price that purchasers are willing to pay. In pure egalitarian systems, governments ensure that everyone receives an equal distribution of resources (Johnson-Lans, 2006). The health care sector has more government intervention than other sectors of the national economy because of the uncertainty in the demand for, and provision of, services. In the United States, state and federal governments play major roles as financiers and payers of health care through the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children’s Health Insurance programs. Medicare is the federal insurance program established in 1965 for persons older than 65 years, as well as for selected populations with severe and chronic disabilities. The Medicare program is divided into four parts (Medicare A, B, C, and D) and provides benefits for hospitalization, limited nursing home care, physicians’ services, medical supplies, outpatient services, and most recently, prescription drugs. In comparison, Medicaid, also established in 1965, is a joint federal and state-funded insurance program that provides medical and health-related services to America’s poorest people. Each state administers its own Medicaid program and sets eligibility requirements for program participation and the type of benefits and services covered. The State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) was established in 1997 as part of the Federal Balanced Budget Act to extend health insurance benefits to children of families who do not qualify for the Medicaid program but are unable to buy private health insurance. Together, Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP financed $661 billion in health care services in 2005—one third of the country’s total health care bill and almost three quarters of all public spending on health care (Hoffman, Klees, & Curtis, 2007). Economic theory predicts that as demand increases, so will supply; the pricing mechanism, in the form of wages and other benefits, will create a balance (equilibrium) between firms in need of workers and individuals who are willing to work for the wage offered. When examining the market for labor, economists assume that households have primary and secondary wage earners. Because a very high proportion of nurses are married, they are considered to be part of two-earner families and therefore have more flexibility to respond to employment opportunities as real wages change or in relation to the employment situation of their spouses (Johnson-Lans, 2006). Nurses’ decisions to enter the work force, as well as how many hours they work while employed, are cyclical in nature. In fact, there have been cyclical shortages and surpluses of nurses documented since the 1960s. Current data show that nursing personnel are in high demand as evidenced by an estimated 2.5 million open registered nurse positions across the United States (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007). In addition to the current need for nurses, employment opportunities in the health care sector are expected to grow at a rapid rate, with a 25% projected increase for registered nurses and physician assistants, and a 33% increase in health care support occupations, such as personal and home health care aides (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2007). The demand for health care professionals and paraprofessionals is on the rise to care for the nation’s 78 million aging baby boomers. Although employment opportunities in health care are on the rise, the nursing profession is in the midst of a cyclical and worsening shortage that began in 1998, making it the longest in modern history (Buerhaus, Staiger, & Auerbach, 2008; Spetz, 2004). Shortage is defined as the excess of the quantity demanded over the quantity supplied at market prices (Folland et al., 2007). The National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses, a comprehensive survey carried out every 4 years to examine trends in the nation’s nursing workforce, revealed that the years between 1996 and 2000 marked the slowest growth in the registered nurse population during the 20-year period between 1980 and 2000. On average, the registered nurse population grew only 1.3% each year between 1996 and 2000 compared with average annual increases of 2% to 3% in earlier years. New estimates show that for the period between 2000 and 2004, the number of registered nurses grew by almost 8% to a new high of 2.9 million (Hager et al., 2006). Although progress has been made in expanding the supply of nurses, economists estimate an anticipated shortage of 285,000 registered nurses between 2015 and 2020 (Buerhaus et al., 2008). Box 7-2 and Figure 7-1 illustrate a forecasting model to predict changes in the nursing workforce. In a well-functioning market, a shortage should be resolved by wage increases until a balance is restored (equilibrium) between organizations in need of workers and workers who are willing to participate in the labor force. One argument used to explain the chronic shortage of nurses is the notion that nurses are underpaid and it is the low wages, relative to other health professionals, as well as other job opportunities outside of nursing and health care, that keep individuals from participating in the workforce as registered nurses. From a purely economic perspective, linking the labor shortage to low wages is curious, in that it violates the basic assumptions of supply and demand. The monopsony model, which examines how employers set wages and make decisions about hiring workers is used to explain this puzzle and provides a partial explanation as to why the market for registered nurses does not conform to the predictions of supply and demand. More specifically, the monopsony model explains the coexistence of high vacancy rates and lower-than-competitive wages for nurses (Johnson-Lans, 2006). Although nurses are employed in a number of community settings, hospitals are the main employer of nurses. Approximately 56% of registered nurses are employed in acute care hospital settings (Hager et al., 2006). Therefore most of the information about the market for nursing labor is understood within the context of hospitals. The monopsony model is based on the assumptions that (1) the market has one dominant buyer (employer) or perhaps a few employers in a regional market who control the demand for workers and (2) all persons who do the same work are paid the same wage. Because workers are paid the same wage, if the employer has to offer a higher wage to get additional workers, it must also raise the wages of the workers that it already employs. Eventually, all of the operating budget would go to paying salaries and the hospital would not be able to make a surplus or profit. As discussed previously, organizations need to make a surplus to stay in business. Additionally, nurses who are currently employed may respond to the higher wages by working overtime hours, taking a second job, or changing from part-time to full-time employment. These responses typically increase the short-term supply of nurses participating in the workforce in RN roles. In the long term, the increased wages offered by hospitals and other organizations influence individuals’ decisions to enter the nursing profession and are one mechanism to ensure an adequate supply of nurses (Buerhaus, 2008). Evidence suggests that increases in nurses’ wages have reduced the nursing shortage. As of 2004 the average annual earnings for registered nurses were $57,785 (Hager et al., 2006). Buerhaus (2008) reports that between 2002 and 2006 real wages for nurses in the United States increased an average of 6.9%, producing the expected drop in hospital registered nurse vacancy rates from a national average of 13% reported in 2001 to 8.1% by 2006. Although there have been reports in the popular media about hospitals’ somewhat extravagant tactics to attract nurses—for instance, $100,000 annual salaries for experienced nurses and other incentives such as flat-screen TVs, gift certificates, and car leases (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009)—it is likely that hospitals will begin instituting wage controls in response to the unfolding national recession of 2008-2009, possibly exacerbating the nursing shortage. Wage control, or a freeze on nurses’ salaries, is viewed as one way to keep hospital operating costs in check. Historical data on prior nursing shortages suggest that freezing nurses’ wages in the face of increasing demand for nursing labor, as characterized by current conditions, will lengthen the duration of a shortage once it begins (Buerhaus, 2008). Given the changing population demographics in combination with the existing labor shortage, widespread use of wage controls may have destructive consequences for the nursing profession, patients, and hospitals. It is important to note that nurses’ decisions to participate in the workforce are complex and not fully explained by economic theory. Managerial and public policies targeting cost containment, such as efforts to reduce in-patient length of stay (LOS), have had a great impact on the working conditions of nurses and have contributed to the duration of the current shortage (Aiken, 2008). Strong evidence suggests that attributes of the organizational environment, also referred to as the nursing practice environment, factor into individual nurses’ decisions to stay employed at a particular hospital or to participate in the workforce in the capacity as a registered nurse. Organizational factors such as work load, managers’ leadership style, autonomy over nursing practice, promotion opportunities, and work schedules also contribute to nurses’ decisions to work (Aiken, 2008; Brewer et al., 2006; Hayes et al., 2006). In their position statement for health system reform, the American Nurses Association advocates for a number of workplace changes to promote the recruitment and retention of nurses and the sustainability of autonomous professional nursing practice (American Nurses Association, 2008). In the physician arena an imbalance exists between generalists and specialists, resulting in a shortage of primary care physicians (Hauer et al., 2008; Mitka, 2007). This disparity between consumer demand and physician supply creates favorable opportunities for advanced practice nurses to practice in primary care centers as physician substitutes. Nurses are making arguments for their use as substitutes for more expensive providers of care for services that they have been formally trained to provide. For example, nurse practitioners work as primary care providers in hospital-based outpatient clinics. Similarly, health care delivery organizations, in an effort to reduce input costs, are incorporating the use of unlicensed personnel as substitutes for nurses for those activities that do not require licensure. For example, hospitals and other delivery organizations have changed the nursing staff skill mix to include registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and nursing assistants. Thus nurses are both substituting for some types of providers and being substituted by other types of providers. With advanced practice nurses working as physician substitutes, competition between these two providers can occur on the basis of cost effectiveness. Studies have demonstrated that the use of advanced practice nurses as primary care providers can reduce costs of outpatient care, including laboratory costs, per-visit costs, per-episode costs, and long-term management costs (Brown & Grimes, 1993; Fulton & Baldwin, 2004; Schroeder, 1993; U.S. Congress, 1986). Nurse-managed services are typically those services offered by advanced practice nurses (nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists) based on the nursing philosophy emphasizing health promotion and preventative care—for example, chronic disease management, case management, or primary care. Research studies have documented that nurse-managed care, when compared with physician-managed care, reduces the frequency of hospitalizations, reduces the acuity of those admitted, reduces lengths of stay, reduces the cost of hospitalization, and results in equivalent ratings for patient satisfaction with service delivery (Brooten, Youngblut, Kutcher, & Bobo, 2004; Mundinger et al., 2000). Given the evidence for the efficacy of nurse-managed services, nurse leaders are developing arguments that move beyond comparing advanced practice nurses as substitutes and complements to physician services and focus on the unique aspects and additional value of advanced practice nurses in achieving optimal patient outcomes (Kleinpell & Gawlinski, 2005; Lin, Gebbie, Fullilove, & Arons, 2004; Mundinger, 2002). Retail clinics differ from urgent care clinics in that they are located within discount stores, grocery stores, or drug stores; are staffed by either nurse practitioners or physician assistants; and offer a limited set of basic medical and preventative services. Retail clinics are an emerging trend whereby advanced practice nurses act as substitutes for physicians to meet consumers’ desire for more convenient and lower-cost medical care. Health care services typically offered at retail clinics include preventative care such as immunizations and blood pressure screening, as well as treatment for upper respiratory, sinusitis, ear, or urinary tract infections. Clients mainly pay for retail visits out of pocket, although in recent years many insurance companies, including Medicare and Medicaid, will pay for these visits (Mehrotra, Wang, Lave, Adams, & McGlynn, 2008). There are now more than 700 retail clinics throughout the United States, and their numbers are expected to reach 3000 within 5 years (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2008). Retail clinics offer an alternative to urgent care clinics and emergency departments for simple acute problems. Despite the national shortage of primary care physicians, the emergence of these nurse-led clinics has drawn the ire of some medical societies, who question their quality and are asking for increased regulation. For instance, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and several state medical societies are recommending certain operating requirements, including limits on the scope of clinical services, the creation of referral systems with physician practices, and the use of electronic patient records (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2008). In an early evaluation comparing the client demographics of, and reasons for, visits to retail clinics, primary care physicians, and emergency departments, Mehrotra and colleagues (2008) found that retail clinics show signs of becoming safety net providers by offering services to a population that is currently underserved by primary care physicians. Clients seen at retail clinics were more likely to be young adults, between the ages of 18 and 44, who pay out of pocket for their care and are less likely to have an existing relationship with a primary care provider. Approximately 90% of retail clinic visits focus on treating 10 minor acute conditions; these same conditions represent 13% of adult primary care physician visits, 30% of pediatric primary care physician visits, and 12% of emergency department visits. These early data suggest that nurse-led retail clinics serve an important role in expanding access to primary care services and relieve the stress on emergency departments. Whether there will be continued expansion and a widespread shift of uncomplicated acute care services from primary care physicians and emergency departments to retail clinics remains to be seen. Because medical care is costly and it is difficult to predict when one might need medical services, insurance functions as a buffer from the financial risks associated with treating illness or disease. People buy insurance as a way to avoid the risks and associated costs of illness and seeking medical treatment. A number of risks are associated with health. There is a risk to one’s health or life associated with illness or disease. There is the additional risk that a given treatment course will not cure or alleviate the underlying disease. Also, there may be unavoidable harm from the treatment itself or by the lack of skill or negligence on the part of the provider. There is a risk of incurring the costs that may be substantial to pay for any treatments. Individuals can take certain actions to reduce the risk of illness—getting vaccinations, avoiding dangerous environments, or leading a health lifestyle—but this considerable risk still remains largely uncertain (Johnson-Lans, 2006). People buy health insurance to avoid the risk of having to pay for expensive medical care. Stated a different way, people are “risk averse” and try to safeguard their wealth or resources by buying insurance as protection from the financial consequences of an unpredictable event. Economists view risk aversion as a characteristic of people’s utility functions. Marginal utility is the extra satisfaction, welfare, or well-being (utility) gained from consuming one more unit of a good or service. In the case of insurance, it is believed that people are more likely to buy insurance to cover low-probability events involving large losses than high-probability events that are associated with small losses (Johnson-Lans, 2006). Although it is difficult to predict when an individual will become sick or need expensive medical care, the risk for large numbers of people (or the expected value of all losses averaged over all people) is quite predictable. Insurance spreads risk across a group of people and involves a series of trades between people. This practice is known as risk pooling. Money is shifted between people who are healthy to people who are sick and in need to pay for expensive medical care. Insurance pools potential losses, but it does not eliminate or reduce the losses. That is, insurance companies specialize in pricing risks, not in taking risks. Insurance companies sell policies to large groups of people with predictable or average risks. Members pay a premium, which covers all losses across the group of policy holders as well as management fees (Getzen, 2004). Moral hazard occurs when a person’s behavior changes based on his or her insurance coverage. In the event of an illness or other adverse event, the insured person is offered medical care at a reduced price. Moral hazard in health insurance markets occurs to the extent that insurance increases the quantity of medical care used (Chernew, Hirth, Sonnad, Ermann, & Fendrick, 1998; Freeman, Kadiyala, Bell, & Martin, 2008; Jonhson-Lans, 2006; Newhouse, 1992). One way that insurance companies offset the risk of moral hazard is to require cost sharing with consumers. Deductibles and co-payments are two commonly used methods. Co-payment is a sharing relationship between the consumer and the insurance company, as specified in a given policy. When consumers seek medical care, the insurance company pays for some of the costs and the consumer pays for the remainder (the co-payment). A deductible is a fixed amount that the consumer must pay toward a medical bill each year before any insurance payments are made. Deductibles are designed to generate more prudent care decisions on the part of the policy holder because they dissuade consumers from submitting claims to the insurance company for “small” losses or minor services (Getzen, 2004). Consumers purchase health care depending on their perceptions of the impact of the care on their health (McMenamin, 1990). That is, consumers purchase health care, but their actual desire, with a few exceptions, is health. Thus the demand for health care “is derived from the more basic demand for health” (Feldstein, 1983, p. 81). The decision to purchase health care also depends on the cost of care to the consumer. Total consumer costs of health care include monetary costs (co-payment, deductibles, insurance premiums, out-of-pocket expenses, and lost time from wages and work), as well as nonmonetary costs (e.g., risk, pain, inconvenience). The demand for health care also depends on the willingness of consumers to purchase services after weighing the expected benefits of the care against the costs of the care. If consumers carry insurance, their direct out-of-pocket expenses for the care will be less than if they are uninsured (Feldstein, 1983). Therefore the insurance status of consumers has an impact on the costs of care (to the consumers) and thus their demand for care. Demand for specific services is also influenced by the recommendations and decisions of health care providers (Feldstein, 1983). Because providers of care possess more knowledge regarding treatment options than consumers do, the practice styles of providers, as well as how much information they share with consumers, can greatly affect the demand and consumption of services (Devers, Brewster, & Casalino, 2003; Rice & Labelle, 1989). Similarly, the risk of litigation by consumers can result in a “defensive” practice style by providers. Fear of litigation can lead to overprescription of (often unnecessary) diagnostic tests or therapeutic interventions and ultimately result in higher health care costs. The demand for health care services is not directly related to the amount or quality of services purchased as in other industries. This, in conjunction with the high levels of uncertainty and the unequal information among consumers, providers, and payers, leads to a situation called market failure. Market failure is characterized by the inability of buyers and sellers to strike a balance in the supply and demand of goods and services and ultimately fail to produce a socially desirable level of output. For example, variation in the quality of care is an example of market failure arising from imperfect consumer information about physician practice patterns. This implies that some patients are getting too much treatment and some too little treatment. In fact, it is well documented that many Americans do not receive care that is based on the best scientific knowledge (Institute of Medicine, 2001). More generally, supply-side drivers leading to market failure include the cost of care for hospital and physician services, access to care because of the prohibitive cost of health insurance, and medical outcomes and population health status in light of invested resources. Demand-side factors of market failure in health care include third-party insurance mechanism, in which the insurance company or government entity under the Medicare and Medicaid programs is the primary purchaser of health care services (Henderson, 2008). There are four dominant methods consumers use to pay for their health care in the United States: out-of-pocket payment, private individual insurance, employer-sponsored group insurance, and public or government-sponsored individual or group insurance. Each of these payment modes can be viewed as a historical progression and as a categorization of current health care financing (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2005). Private individual insurance: This form of financing adds a third party (the insurance company) to the relationship between the consumer and provider. Payment for health care services is divided into two parts, a premium paid by the individual to the insurance company and a reimbursement payment to the provider from the insurance company. Indemnity insurance adds a third payment transaction: a reimbursement to the individual from the insurance company. Because of the administrative costs in managing these transactions, individual health insurance never became a dominant method of paying for health care (Starr, 1982). Currently, individual policies provide health insurance for only 3% of the U.S. population (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2008). Because of the growing burden of uninsurance and underinsurance, individual policies are gaining acceptance as a plausible way to expand insurance benefits, although their use remains limited (Claxton et al., 2007). Employer-sponsored group insurance came into being during the Great Depression and expanded rapidly after World War II. The American Hospital Association first established the Blue Cross of California in 1939, offering hospital insurance to groups of workers. The first employer-based insurance plans were initiated by physicians and hospitals that were seeking a steady source of income, generous reimbursements, and protection from cost controls (Starr, 1982), all of which had declined during the Great Depression because people were not able to pay for their medical and hospital expenses out of pocket. With employer-based insurance, the employer pays most of the premium to purchase health insurance on behalf of their employees. Thus in the United States, health insurance became a benefit of employment. The government treats employee health benefits as a tax-deductible business expense for employers. Because each dollar of employer-sponsored health insurance results in a reduction in taxes collected, the federal government is in essence subsidizing employer-sponsored insurance. This subsidy is estimated to be about $168 billion per year (Employment Benefits Research Institute, 2008). Insurance increased the demand for, and cost of, medical services, which become difficult to control. Moreover, individuals not participating in the labor force, especially the elderly and those with chronic conditions or low incomes, found it increasingly difficult to buy insurance on their own. This lead to the creation of the government-sponsored Medicare and Medicaid programs in the mid-1960s and the more recent State Children’s Health Insurance Program in 1997. In comparison, the state-funded Medicaid program is funded by taxpayer contributions, although not all taxpayers are eligible for Medicaid benefits. Because these programs are tax-funded, there is a double subsidy at play for taxpayers. As with private insurance, benefits are shifted from those who are healthy to those who are sick. The government-sponsored programs add an additional distribution of funds between the wealthy and the poor. That is, the healthy middle-income employees generally pay more Social Security taxes than they receive in health services. Unemployed, disabled, and lower-income elderly persons may receive more in health services than they contribute in taxes (Bodenheimer & Grumbach, 2005).

Economic Issues in Nursing and Health Care

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Health Economics

Health Economics

UNCERTAINTY

INSURANCE AND THIRD-PARTY PAYMENT

PROBLEMS WITH INFORMATION

LARGE ROLE OF NONPROFIT FIRMS

RESTRICTIONS ON COMPETITION

ROLE OF EQUITY AND NEED

GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES AND PUBLIC PROVISION

![]() Economic Concepts Specific to the Nursing Profession

Economic Concepts Specific to the Nursing Profession

UNDERSTANDING THE SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR NURSES

MONOPSONY POWER OF HOSPITALS

NURSES AS COMPLEMENTS AND SUBSTITUTES FOR PHYSICIANS

![]() Economic Concepts for Advocacy and Professional Practice

Economic Concepts for Advocacy and Professional Practice

PAYING FOR HEALTH CARE: INSURANCE, NATIONAL HEALTH EXPENDITURES, AND ACCESS TO CARE

TYPES OF INSURANCE

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access