Chapter 28 ECG

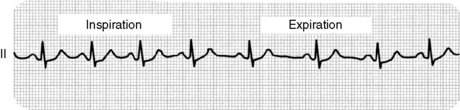

1 An ECG recorded in a 30-year-old healthy woman is shown in Figure 28-1. How would you interpret this ECG?

Figure 28-1 shows respiratory sinus arrhythmia, a normal finding. Typically the heart rate increases slightly with inspiration and, due to increased vagal tone, decreases slightly with expiration. Variation of heart rate with the respiratory cycle is believed to increase the efficiency of gas exchange by the lungs.

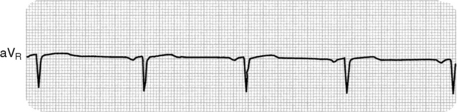

2 An ECG recorded in a febrile septic patient is shown in Figure 28-2. How would you interpret this ECG?

Figure 28-2 shows sinus tachycardia, as might be expected in a febrile septic patient. Each QRS complex is preceded by a P wave, so the rhythm is sinus. The heart rate is also quite elevated at close to 150 beats/min, so this is sinus tachycardia.

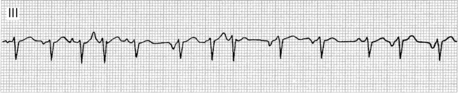

3 An ECG recorded in a healthy middle-aged man after he became dizzy and diaphoretic while having blood drawn is shown in Figure 28-3. How would you interpret this ECG?

Figure 28-3 shows a slow heart rate (bradycardia). Each QRS complex is preceded by a P wave, so the rhythm is sinus. Bradycardia is characterized by a heart rate of less than 50 beats/min. A common cause is vagal hyperactivity, as may occur with pain or vomiting, as well as with numerous medications, such as beta blockers.

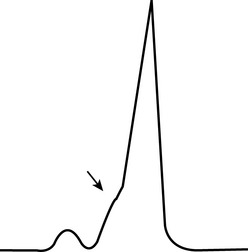

4 The patient whose ECG is shown in Figure 28-4 will almost certainly remain asymptomatic throughout life but is at marginally increased risk for sudden cardiac death. How would you interpret this ECG (hint: the arrow is a giveaway)?

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by a shortened PR interval and a widened QRS complex with a slurred upstroke (delta wave). Patients with WPW syndrome have an accessory pathway through which action potentials may travel between the atria and ventricles; this is represented by the delta wave on Figure 28-4 (shown by arrow). Unlike the atrioventricular (AV) node, this accessory pathway is unable to slow transmission of action potentials from atria to ventricles. As a result, tachyarrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation can cause marked increase in the rate of ventricular contraction. Such dysrhythmias in WPW patients are dangerous because the resulting ventricular tachycardia can degenerate into potentially fatal ventricular fibrillation.

Figure 28-4 Electrocardiogram in asymptomatic adult.

(From Ferri F: Practical Guide to the Care of the Medical Patient, 8th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2011.)

5 The ECG shown in Figure 28-5 comes from a 52-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) following admission to the hospital with pneumonia. How would you interpret this ECG (hint: look at the p waves)?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree