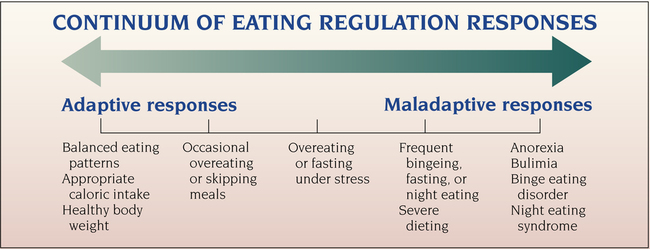

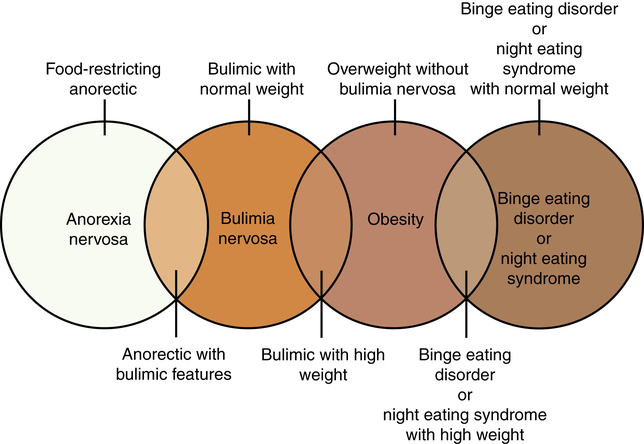

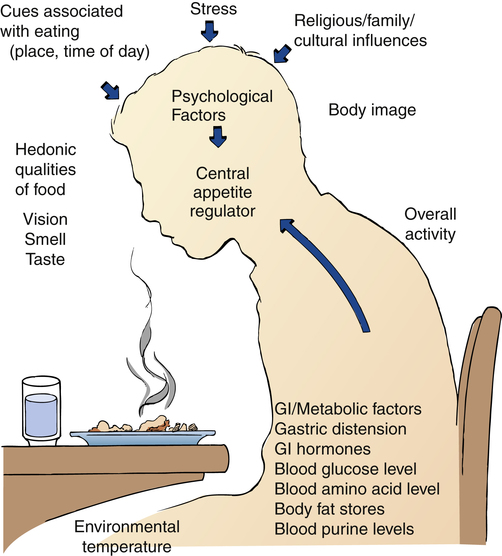

1. Describe the continuum of adaptive and maladaptive eating regulation responses. 2. Identify behaviors associated with eating regulation responses. 3. Analyze predisposing factors, precipitating stressors, and the appraisal of stressors related to eating regulation responses. 4. Describe coping resources and coping mechanisms related to eating regulation responses. 5. Formulate nursing diagnoses related to eating regulation responses. 6. Examine the relationship between nursing diagnoses and medical diagnoses related to eating regulation responses. 7. Identify expected outcomes and short-term nursing goals related to eating regulation responses. 8. Develop a family education plan to promote adaptive eating regulation responses. 9. Analyze nursing interventions related to eating regulation responses. 10. Evaluate nursing care related to eating regulation responses. punishments. People can have unrealistic images of their ideal body size and desired body weight. Illnesses associated with maladaptive eating regulation responses include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and night eating syndrome (Figure 24-1). They are potentially fatal (Crow et al, 2009). • What do I believe is the ideal body size and shape? • How do I feel about people who are overweight? • Can a person ever really be too thin? • Do I worry about my weight a lot? • Do I have biases about eating and weight that will interfere with my ability to care for patients with eating disorders? Nurses who suspect that they have an eating disorder may not be able to provide care for patients who cannot regulate their eating responses (Hicks et al, 2008). These nurses should seek professional help for themselves before attempting to care for others. An early response to treatment is a good predictor of a successful outcome in bulimia nervosa. A good outcome also is associated with a shorter duration between onset of symptoms and the first treatment intervention (Steinhausen and Weber, 2009). Therefore, early identification of bulimia nervosa is important in preventing a chronic eating disorder. Patients with maladaptive eating regulation responses need to receive a comprehensive nursing assessment that includes complete biological, psychological, and sociocultural evaluations (Himmerich et al, 2010). • A full physical examination should be performed, with particular attention given to vital signs, weight for height and age, skin, the cardiovascular system, and evidence of vomiting or abuse of laxatives, diet pills, or diuretics. • A dental examination may be indicated, and is useful to assess growth, sexual development, and general indicators of physical development. • A psychiatric history, including dieting history, substance use history, family assessment, and medication history, also is needed. These two questions can be easily incorporated into the nursing assessment of all patients. • Actual and desired weight and weight history • Onset and pattern of menstruation • Food avoidances, restrictions, dieting, and fasting patterns • Frequency, extent, and timing of binge eating or purging or both • Unusual beliefs about nutrition • Use of laxatives, diuretics, diet pills, and other methods of purging • Weight and shape preoccupations • Food preferences and peculiarities People with a maladaptive eating regulation response usually have some type of associated physical problem. The various complications associated with eating disorders are listed in Box 24-1. In anorexia nervosa, metabolic and endocrine abnormalities result from the reaction of the body to the malnutrition associated with starvation. All body systems are affected. Most commonly seen are amenorrhea, osteoporosis, and hypometabolic symptoms, such as cold intolerance and bradycardia (Smith and Wolfe, 2008). Starvation may cause hypotension, constipation, and acid-base and fluid-electrolyte disturbances, including pedal edema. Patients with bulimia have increased rates of anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and mood disorders (Hirth et al, 2011). People with antisocial personality disorders are six to seven times more likely to have bulimia than the general population. Biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors may predispose a person to the development of an eating disorder (Roman and Reay, 2009). These factors are involved in the regulation and control of food intake and reflect a combination of genetic, neurochemical, developmental, personality, social, cultural, and familial elements (Figure 24-3). Finally, gray matter loss in the anterior cingulated cortex of the brain has been found to be related to the severity of anorexia nervosa, indicating an important role of this area in the pathophysiology of the disorder (Fladung et al, 2010). Ongoing research promises to shed more light on the biological factors that may predispose a person to maladaptive eating regulation responses (Brewerton, 2011; Marsh et al, 2011). Parents who overemphasize athletics, reward slimness, or express disapproval of overweight people are placing their children at risk for development of eating disorders. Parents who continually skip meals, eat when distressed, and otherwise role model poor nutritional habits are not teaching children about the appropriate value of food as nourishment. An important preventive nursing intervention involves educating the parents of young children regarding healthy eating behaviors (Table 24-1). TABLE 24-1 FAMILY EDUCATION PLAN

Eating Regulation Responses and Eating Disorders

Continuum of Eating Regulation Responses

Prevalence of Eating Disorders

Anorexia Nervosa

Bulimia Nervosa

Assessment

Medical Complications

Psychiatric Complications

Predisposing Factors

Biological

Environmental

Preventing Childhood Eating Problems

CONTENT

INSTRUCTIONAL ACTIVITIES

EVALUATION

Describe self-demand feeding and its importance in healthy eating behaviors.

Explore parents’ current feeding practices and understanding of healthy eating.

Provide information to enhance knowledge of healthy eating behaviors.

Parents will identify healthy eating behaviors and self-demand feeding and begin to explore how their relationship with food influences their children’s eating.

Describe the physiological and psychological signs of hunger and satiety, as well as the meaning and difference of both types of signs.

Explore parents’ own signs of hunger and satiety, and have parents describe children’s signs.

Parents will keep a hunger diary to record physical and psychological signs of hunger and satiety for themselves and their children.

Describe the danger of psychological hunger.

Explain the use of a hunger diary, which is a daily journal regarding signs of hunger.

Parents will be able to distinguish between psychological and physical hunger.

Explore myths about feeding, such as “cleaning the plate” and “eating because other children are starving.”

Describe the importance of allowing children to determine their feeding needs and the relationship of healthy eating to children’s ability to differentiate between physical and psychological signs of hunger and satiety.

Give a homework assignment for each parent to interview three other adults about their current eating practices and memories of eating.

Parents will complete homework assignment, discuss interview experiences, and describe how perpetuating myths about feeding can harm their children.

Implement self-demand feeding at particular developmental stages of children.

Review the eating stages children experience and the potential problems they may have at each stage.

Parents will discuss the developmental stages of their children and plan to implement self-demand feeding.

Discuss parental experiences related to implementing self-demand feeding.

Review parents’ expectations and experiences with implementing self-demand feeding.

Parents will relate any problem with implementing self-demand feeding.

Nurse will evaluate family for further education and plan for follow-up if necessary.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Eating Regulation Responses and Eating Disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access