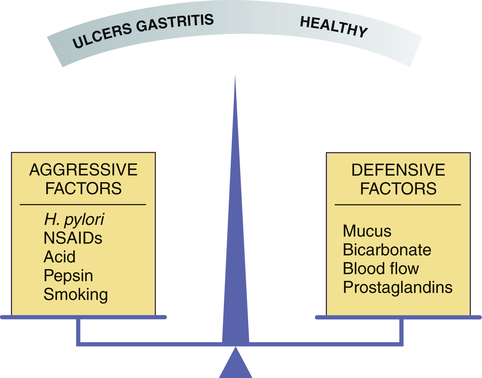

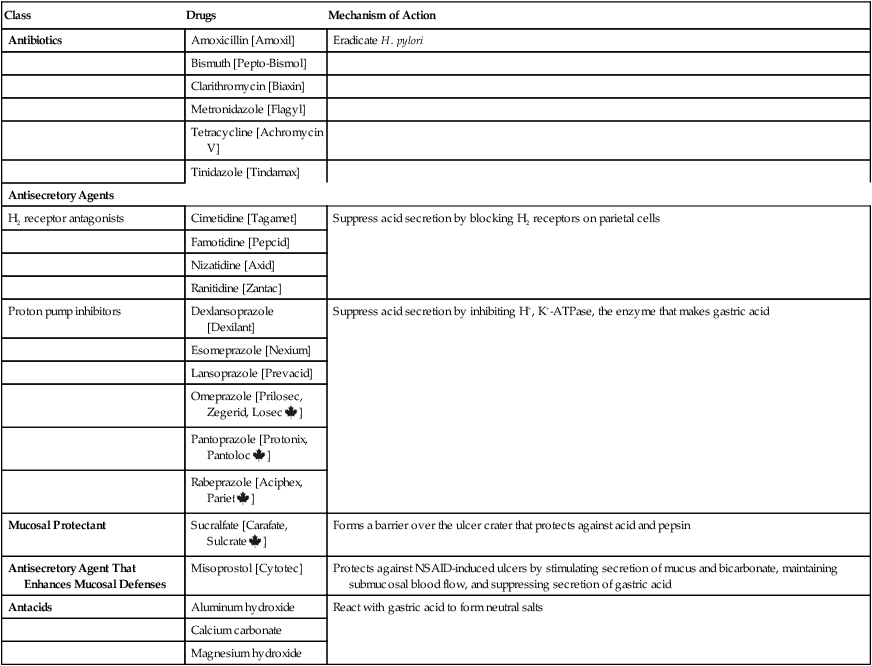

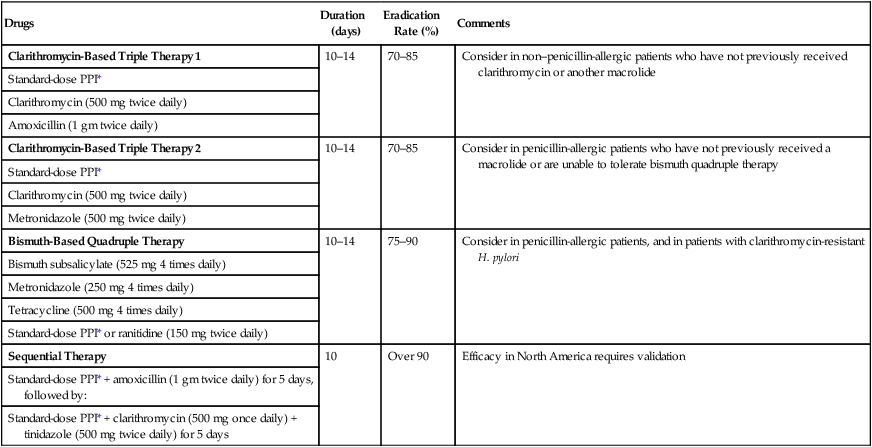

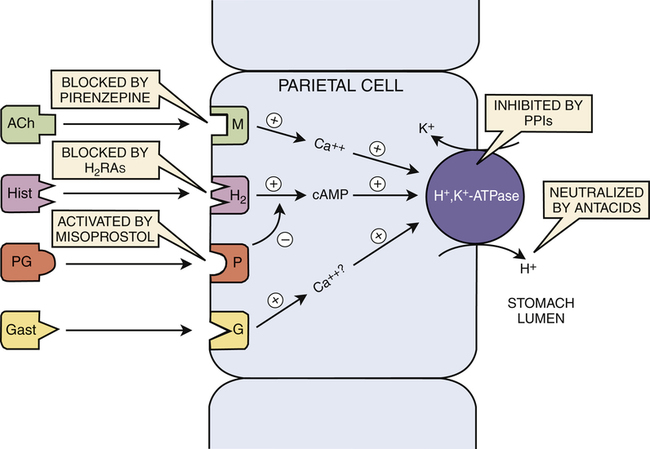

CHAPTER 78 Peptic ulcers develop when there is an imbalance between mucosal defensive factors and aggressive factors (Fig. 78–1). The major defensive factors are mucus and bicarbonate. The major aggressive factors are H. pylori, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gastric acid, and pepsin. NSAIDs are the underlying cause of many gastric ulcers and some duodenal ulcers. As discussed in Chapter 71, aspirin and other NSAIDs inhibit the biosynthesis of prostaglandins. By doing so, they can decrease submucosal blood flow, suppress secretion of mucus and bicarbonate, and promote secretion of gastric acid. Furthermore, NSAIDs can irritate the mucosa directly. NSAID-induced ulcers are most likely with long-term, high-dose therapy. As shown in Table 78–1, the antiulcer drugs fall into five major groups: TABLE 78–1 Classification of Antiulcer Drugs • Antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors, histamine2 receptor antagonists) • Antisecretory agents that enhance mucosal defenses Clarithromycin [Biaxin] suppresses growth of H. pylori by inhibiting protein synthesis. In the absence of resistance, treatment is highly effective. Unfortunately, the rate of resistance is rising, exceeding 20% in some areas. The most common side effects are nausea, diarrhea, and distortion of taste. The basic pharmacology of clarithromycin is presented in Chapter 86. Helicobacter pylori is highly sensitive to amoxicillin. The rate of resistance is low, only about 3%. Amoxicillin kills bacteria by disrupting the cell wall. Antibacterial activity is highest at neutral pH, and hence can be enhanced by reducing gastric acidity with an antisecretory agent (eg, omeprazole). The most common side effect is diarrhea. The basic pharmacology of amoxicillin is discussed in Chapter 84. Tetracycline, an inhibitor of bacterial protein synthesis, is highly active against H. pylori. Resistance is rare (less than 1%). Because tetracycline can stain developing teeth, it should not be used by pregnant women or young children. The pharmacology of tetracycline is discussed in Chapter 86. Metronidazole [Flagyl] is very effective against sensitive strains of H. pylori. Unfortunately, over 40% of strains are now resistant. The most common side effects are nausea and headache. A disulfiram-like reaction can occur if metronidazole is used with alcohol, and hence alcohol must be avoided. Metronidazole should not be taken during pregnancy. The basic pharmacology of metronidazole is discussed in Chapter 99. Tinidazole [Tindamax] is very similar to metronidazole, and shares that drug’s adverse effects and interactions. Like metronidazole, tinidazole can cause a disulfiram-like reaction, and hence must not be combined with alcohol. The basic pharmacology of tinidazole is discussed in Chapter 99. Table 78–2 presents four ACG-recommended regimens. In regions where resistance to clarithromycin is low (below 20%), the preferred treatment is clarithromycin-based triple therapy, consisting of clarithromycin plus amoxicillin plus a PPI. For patients with penicillin allergy, metronidazole can be substituted for amoxicillin. In regions where resistance to clarithromycin is high (above 20%), the preferred regimen is bismuth-based quadruple therapy, consisting of bismuth subsalicylate plus metronidazole plus tetracycline, all three combined with a PPI or an H2RA. For patients who can’t use triple therapy or quadruple therapy, sequential therapy is an option. This regimen consists of taking a PPI plus amoxicillin for 5 days, followed by a PPI plus clarithromycin plus tinidazole for 5 days. At this time, the efficacy of sequential therapy in North America has not been established. TABLE 78–2 First-Line Regimens for Eradicating H. pylori *Standard doses for PPIs are as follows: dexlansoprazole, 30 to 60 mg once daily; esomeprazole, 40 mg once daily; lansoprazole, 30 mg twice daily; omeprazole, 40 mg twice daily; pantoprazole, 40 mg twice daily; and rabeprazole 20 mg twice daily. Adapted from Chey WD, Wong BCY, and Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology: American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 102:1808–1825, 2007. As discussed in Chapter 70, histamine acts through two types of receptors, named H1 and H2. Activation of H1 receptors produces symptoms of allergy. Activation of H2 receptors, which are located on parietal cells of the stomach (Fig. 78–2), promotes secretion of gastric acid. By blocking H2 receptors, cimetidine reduces both the volume of gastric juice and its hydrogen ion concentration. Cimetidine suppresses basal acid secretion and secretion stimulated by gastrin and acetylcholine. Because cimetidine produces selective blockade of H2 receptors, the drug cannot suppress symptoms of allergy. Cimetidine is available over the counter to treat these common acid-related symptoms.

Drugs for peptic ulcer disease

Pathogenesis of peptic ulcers

The relationship of mucosal defenses and aggressive factors to health and peptic ulcer disease.

The relationship of mucosal defenses and aggressive factors to health and peptic ulcer disease.

When aggressive factors outweigh mucosal defenses, gastritis and peptic ulcers result. (NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.)

Aggressive factors

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Overview of treatment

Drug therapy

Classes of antiulcer drugs

Class

Drugs

Mechanism of Action

Antibiotics

Amoxicillin [Amoxil]

Eradicate H. pylori

Bismuth [Pepto-Bismol]

Clarithromycin [Biaxin]

Metronidazole [Flagyl]

Tetracycline [Achromycin V]

Tinidazole [Tindamax]

Antisecretory Agents

H2 receptor antagonists

Cimetidine [Tagamet]

Suppress acid secretion by blocking H2 receptors on parietal cells

Famotidine [Pepcid]

Nizatidine [Axid]

Ranitidine [Zantac]

Proton pump inhibitors

Dexlansoprazole [Dexilant]

Suppress acid secretion by inhibiting H+, K+-ATPase, the enzyme that makes gastric acid

Esomeprazole [Nexium]

Lansoprazole [Prevacid]

Omeprazole [Prilosec, Zegerid, Losec ![]() ]

]

Pantoprazole [Protonix, Pantoloc ![]() ]

]

Rabeprazole [Aciphex, Pariet ![]() ]

]

Mucosal Protectant

Sucralfate [Carafate, Sulcrate ![]() ]

]

Forms a barrier over the ulcer crater that protects against acid and pepsin

Antisecretory Agent That Enhances Mucosal Defenses

Misoprostol [Cytotec]

Protects against NSAID-induced ulcers by stimulating secretion of mucus and bicarbonate, maintaining submucosal blood flow, and suppressing secretion of gastric acid

Antacids

Aluminum hydroxide

React with gastric acid to form neutral salts

Calcium carbonate

Magnesium hydroxide

Antibacterial drugs

Antibiotics employed

Clarithromycin.

Amoxicillin.

Tetracycline.

Metronidazole.

Tinidazole.

Antibiotic regimens

Drugs

Duration (days)

Eradication Rate (%)

Comments

Clarithromycin-Based Triple Therapy 1

10–14

70–85

Consider in non–penicillin-allergic patients who have not previously received clarithromycin or another macrolide

Standard-dose PPI*

Clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily)

Amoxicillin (1 gm twice daily)

Clarithromycin-Based Triple Therapy 2

10–14

70–85

Consider in penicillin-allergic patients who have not previously received a macrolide or are unable to tolerate bismuth quadruple therapy

Standard-dose PPI*

Clarithromycin (500 mg twice daily)

Metronidazole (500 mg twice daily)

Bismuth-Based Quadruple Therapy

10–14

75–90

Consider in penicillin-allergic patients, and in patients with clarithromycin-resistant H. pylori

Bismuth subsalicylate (525 mg 4 times daily)

Metronidazole (250 mg 4 times daily)

Tetracycline (500 mg 4 times daily)

Standard-dose PPI* or ranitidine (150 mg twice daily)

Sequential Therapy

10

Over 90

Efficacy in North America requires validation

Standard-dose PPI* + amoxicillin (1 gm twice daily) for 5 days, followed by:

Standard-dose PPI* + clarithromycin (500 mg once daily) + tinidazole (500 mg twice daily) for 5 days

Histamine2 receptor antagonists

Cimetidine

Mechanism of action

A model of the regulation of gastric acid secretion showing the actions of antisecretory drugs and antacids.

A model of the regulation of gastric acid secretion showing the actions of antisecretory drugs and antacids.

Production of gastric acid is stimulated by three endogenous compounds: (1) acetylcholine (ACh) acting at muscarinic (M) receptors; (2) histamine (Hist) acting at histamine2 (H2) receptors; and (3) gastrin (Gast) acting at gastrin (G) receptors. As indicated, all three compounds act through intracellular messengers—either calcium (Ca++) or cyclic AMP (cAMP)—to increase the activity of H+,K+-ATPase, the enzyme that actually produces gastric acid. Prostaglandins (PG) decrease acid production, perhaps by suppressing production of intracellular cAMP. The actions of histamine2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and other drugs are indicated. (P = prostaglandin receptor.)

Therapeutic uses

Heartburn, acid indigestion, and sour stomach.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drugs for peptic ulcer disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access