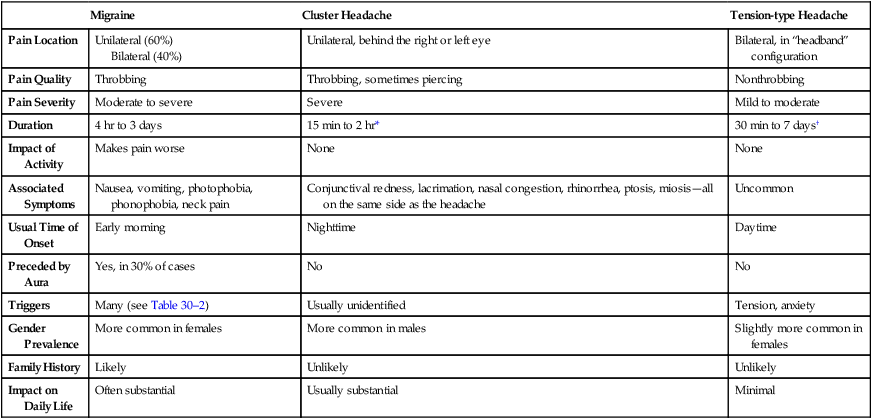

CHAPTER 30 Headache is a common symptom that can be triggered by a variety of stimuli, including stress, fatigue, acute illness, and sensitivity to alcohol. Many people experience mild, episodic headaches that can be relieved with over-the-counter medications, such as aspirin, acetaminophen [Tylenol, others], and ibuprofen [Motrin, Advil, others]. For these individuals, medical intervention is unnecessary. In contrast, some people experience severe, recurrent, debilitating headaches that are frequently unresponsive to aspirin-like drugs. For these individuals, medical attention is merited. In this chapter, we focus on severe forms of headache—specifically, migraine, cluster, and tension-type headaches. Defining characteristics of these headaches are summarized in Table 30–1. TABLE 30–1 Characteristics of Major Headache Syndromes *Headaches occur in clusters that typically consist of one or more headaches (lasting 15 minutes to 2 hours) every day for 2 to 3 months, with a headache-free interval (months to years) between each cluster. †Chronic tension headaches occur at least 15 days/month for 6 months or longer. Migraine headache is characterized by throbbing head pain of moderate to severe intensity that may be unilateral (60%) or bilateral (40%). Most patients also experience nausea and vomiting, along with neck pain and sensitivity to light and sound. Physical activity intensifies the pain. During a prolonged attack, patients develop hyperalgesia (augmented responses to painful stimuli) and allodynia (painful responses to normally innocuous stimuli). Migraines usually develop in the morning after arising. Pain increases gradually and lasts 4 to 72 hours (median duration 24 hours). On average, attacks occur 1.5 times a month. Precipitating factors include anxiety, fatigue, stress, menstruation, alcohol, weather changes, and tyramine-containing foods (Table 30–2). TABLE 30–2 Factors That Can Precipitate Migraine Headache Emotions Stress Foods That Contain: Tyramine (eg, aged cheeses, Chianti wine) Drugs Alcohol Weather Low temperature and low humidity Others Carbon monoxide • Plasma levels of CGRP rise during a migraine attack. • Stimulation of neurons of the trigeminal vascular system promotes release of CGRP, which in turn promotes vasodilation and release of inflammatory neuropeptides. • Dosing with sumatriptan, a drug that relieves migraine, lowers elevated levels of CGRP. • Sumatriptan can suppress release of CGRP from cultured trigeminal neurons. Data that support a protective role for 5-HT include the following: Nondrug measures can help. Patients should try to control or eliminate triggers (see Table 30–2) and should maintain a regular pattern of eating, sleeping, and exercise. Why? Because, in people with migraine, the brain seems to have a low tolerance for the ups and downs of life. Once an attack has begun, the migraineur should retire to a dark, quiet room. Placing an ice pack on the neck and scalp can help. The objective of abortive therapy is to eliminate headache pain and suppress associated nausea and vomiting. Treatment should commence at the earliest sign of an attack. Because migraine causes GI disturbances (nausea, vomiting, and gastric stasis), oral therapy may be ineffective once an attack has begun. Hence, for treatment of an established attack, a drug that can be administered by injection, nasal spray, or rectal suppository may be best. As noted, two types of drugs are used: nonspecific analgesics and migraine-specific agents. Representative drugs are listed in Table 30–3. TABLE 30–3 Migraine Headache: Drugs for Abortive Therapy NONSPECIFIC ANALGESICS Aspirin-like Drugs Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (eg, aspirin, naproxen, diclofenac) Opioid Analgesics Butorphanol MIGRAINE-SPECIFIC DRUGS Ergot Alkaloids Dihydroergotamine [D.H.E. 45, Migranal] Selective Serotonin1B/1D Receptor Agonists (Triptans) Almotriptan [Axert] Use of abortive medications (both nonspecific and migraine specific) should be limited to 1 or 2 days a week. Why? Because more frequent use can lead to medication overuse headache (MOH), also known as drug-induced headache or drug-rebound headache (Box 30–1).

Drugs for headache

Migraine

Cluster Headache

Tension-type Headache

Pain Location

Unilateral (60%)

Bilateral (40%)

Unilateral, behind the right or left eye

Bilateral, in “headband” configuration

Pain Quality

Throbbing

Throbbing, sometimes piercing

Nonthrobbing

Pain Severity

Moderate to severe

Severe

Mild to moderate

Duration

4 hr to 3 days

15 min to 2 hr*

30 min to 7 days†

Impact of Activity

Makes pain worse

None

None

Associated Symptoms

Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, neck pain

Conjunctival redness, lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, ptosis, miosis—all on the same side as the headache

Uncommon

Usual Time of Onset

Early morning

Nighttime

Daytime

Preceded by Aura

Yes, in 30% of cases

No

No

Triggers

Many (see Table 30–2)

Usually unidentified

Tension, anxiety

Gender Prevalence

More common in females

More common in males

Slightly more common in females

Family History

Likely

Unlikely

Unlikely

Impact on Daily Life

Often substantial

Usually substantial

Minimal

Migraine headache

Characteristics, pathophysiology, and overview of treatment

Characteristics

Anticipation

Anxiety

Depression

Excitement

Frustration

Nitrates (eg, cured meat products)

Phenylethylamine (eg, chocolate)

Monosodium glutamate (eg, Chinese food, canned soups)

Aspartame (eg, diet sodas, artificial sweeteners)

Yellow food coloring

Analgesics (excessive use or withdrawal)

Caffeine (excessive use or withdrawal)

Cimetidine

Cocaine

Estrogens (eg, oral contraceptives)

Nitroglycerin

High temperature and high humidity

Major weather change over 1–2 days

High or low barometric pressure

Hormonal changes in females

Flickering lights

Glare

Loud noises

Hypoglycemia

Change in altitude

Pathophysiology

Overview of treatment

Abortive therapy

Acetaminophen + Aspirin + Caffeine [Excedrin Migraine]

Meperidine [Demerol]

Ergotamine [Ergomar]

Ergotamine + Caffeine [Cafergot, Migergot]

Frovatriptan [Frova]

Naratriptan [Amerge]

Eletriptan [Relpax]

Rizatriptan [Maxalt]

Sumatriptan [Imitrex, Sumavel DosePro]

Zolmitriptan [Zomig]

Ergot alkaloids