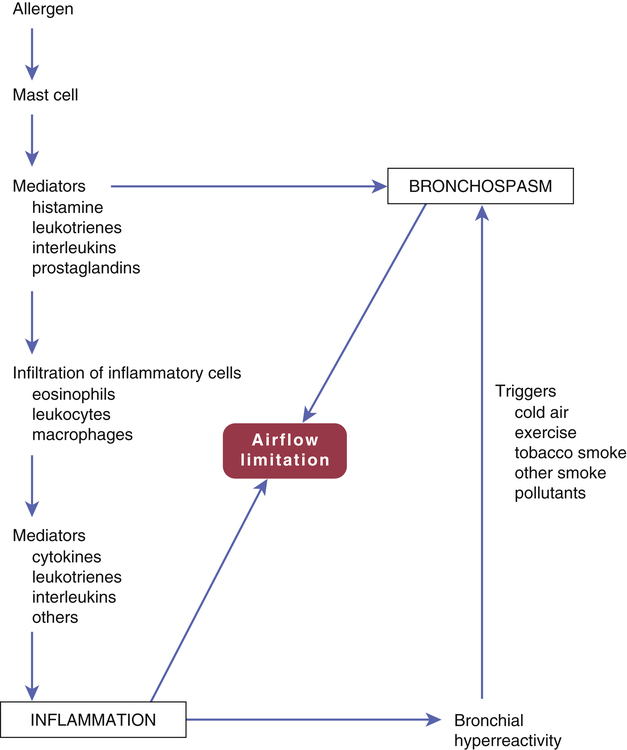

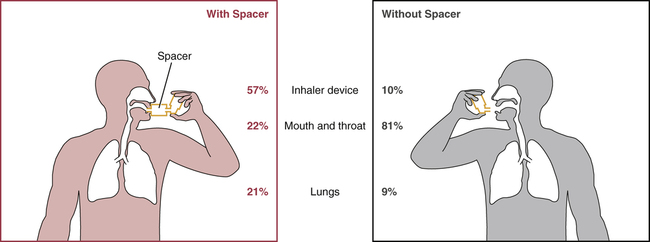

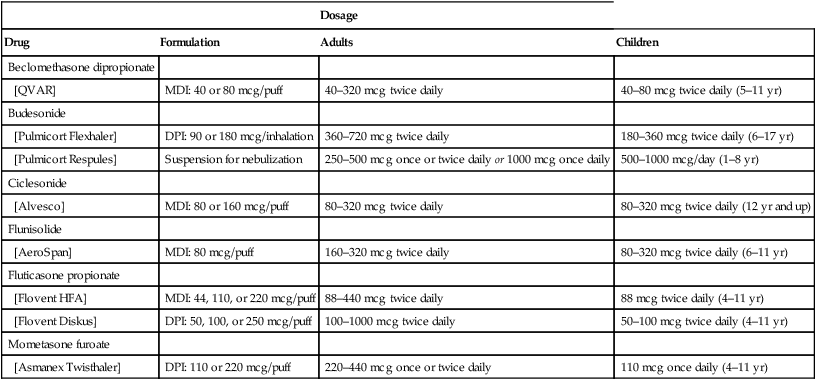

CHAPTER 76 Figure 76–1 depicts the events that lead to inflammation and bronchoconstriction in patients whose asthma is caused by specific allergens. Although this model may not apply completely to all asthma patients, it nonetheless provides a basis for understanding the drugs used for treatment. The inflammatory process begins with binding of allergen molecules (eg, house dust mite feces) to immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies on mast cells. This causes mast cells to release an assortment of mediators, including histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and interleukins. These mediators have two effects. They act immediately to cause bronchoconstriction. In addition, they promote infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells (eosinophils, leukocytes, macrophages). These inflammatory cells then release mediators of their own. The end result is airway inflammation, characterized by edema, mucus plugging, and smooth muscle hypertrophy, all of which obstruct airflow. In addition, inflammation produces a state of bronchial hyperreactivity. Because of this state, mild trigger factors (eg, cold air, exercise, tobacco smoke) are able to cause intense bronchoconstriction. The major drugs for asthma are listed in Table 76–1. As indicated, they fall into two main pharmacologic classes: anti-inflammatory agents and bronchodilators. The principal anti-inflammatory drugs are the glucocorticoids. The principal bronchodilators are the beta2 agonists. For chronic asthma, glucocorticoids are administered on a fixed schedule, almost always by inhalation. Beta2 agonists may be administered on a fixed schedule (for long-term control) or PRN (to manage an acute attack). Like the glucocorticoids, beta2 agonists are usually inhaled. As discussed in Box 76–1, the drugs we use for asthma are also used for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). TABLE 76–1 Overview of Major Drugs for Asthma ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS Glucocorticoids Inhaled Beclomethasone dipropionate [QVAR] Budesonide [Pulmicort Flexhaler, Pulmicort Respules] Ciclesonide [Alvesco] Flunisolide [AeroSpan] Fluticasone propionate [Flovent HFA, Flovent Diskus] Mometasone furoate [Asmanex Twisthaler] Oral Prednisolone Prednisone Leukotriene Modifiers Montelukast, oral [Singulair] Zafirlukast, oral [Accolate] Zileuton, oral [Zyflo, Zyflo CR] Cromolyn Cromolyn, inhaled [Intal] IgE Antagonist Omalizumab, subQ [Xolair] BRONCHODILATORS Beta2-Adrenergic Agonists Inhaled: Short Acting Albuterol [AccuNeb, ProAir HFA, Proventil HFA, Ventolin HFA] Levalbuterol [Xopenex, Xopenex HFA] Pirbuterol [Maxair Autohaler]*,† Inhaled: Long Acting‡ Arformoterol [Brovana]‡ Formoterol [Foradil Aerolizer, Perforomist]‡ Indacaterol [Arcapta Neohaler]† Salmeterol [Serevent Diskus]‡ Oral Albuterol [VoSpire ER] Terbutaline (generic only) Methylxanthines Theophylline, oral [Theo-24, Theochron, Elixophyllin] Anticholinergics Ipratropium, inhaled [Atrovent HFA] Tiotropium, inhaled [Spiriva] ANTI-INFLAMMATORY/BRONCHODILATOR COMBINATIONS Budesonide/formoterol, inhaled [Symbicort] Fluticasone/salmeterol, inhaled [Advair Diskus, Advair HFA] Mometasone/formoterol, inhaled [Dulera] *This formulation of pirbuterol will be phased out by December 31, 2013. A replacement formulation is in development. †Approved only for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, not asthma. ‡For treatment of asthma, must always be combined with an inhaled glucocorticoid. Several kinds of spacers are available for use with MDIs. All of these devices, which attach directly to the MDI, serve to increase delivery of drug to the lungs and decrease deposition of drug on the oropharyngeal mucosa (Fig. 76–2). Some spacers contain a one-way valve that activates upon inhalation, thereby obviating the need for good hand-lung coordination. Some spacers also contain an alarm whistle that sounds off when inhalation is too rapid. Glucocorticoids (eg, budesonide, fluticasone) are the most effective antiasthma drugs available. Administration is usually by inhalation, but may also be IV or oral. Adverse reactions to inhaled glucocorticoids are generally minor, as are reactions to systemic glucocorticoids taken acutely. However, when systemic glucocorticoids are used long term, severe adverse effects are likely. The basic pharmacology of the glucocorticoids is presented in Chapter 72. Discussion here is limited to their use in asthma. • Decreased synthesis and release of inflammatory mediators (eg, leukotrienes, histamine, prostaglandins) • Decreased infiltration and activity of inflammatory cells (eg, eosinophils, leukocytes) • Decreased edema of the airway mucosa (secondary to a decrease in vascular permeability) Adrenal suppression is of particular concern. As discussed in Chapter 72, prolonged glucocorticoid use can decrease the ability of the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids of its own. Because high levels of glucocorticoids are required to survive severe stress (eg, surgery, trauma, infection), and because adrenal suppression prevents production of endogenous glucocorticoids, patients must be given increased doses of oral or IV glucocorticoids at times of stress. Failure to do so can prove fatal! Following withdrawal of oral glucocorticoids (or transfer to inhaled glucocorticoids), several months are required for recovery of adrenocortical function. Throughout this time, all patients—including those switched to inhaled glucocorticoids—must be given supplemental oral or IV glucocorticoids at times of severe stress. A complete list of contraindications to oral glucocorticoids is presented in the Summary of Major Nursing Implications at the end of this chapter. Six glucocorticoids are available for inhalation (Table 76–2). Four are available in MDIs, three are available in DPIs, and one is available in suspension for nebulization. Inhaled glucocorticoids are administered on a regular schedule—not PRN. Pediatric and adult dosages are summarized in Table 76–2. In all cases, the dosage should be kept as low as possible to minimize adrenal suppression, possible bone loss, and other adverse effects. TABLE 76–2 Inhaled Glucocorticoids: Formulations and Dosages

Drugs for asthma

Basic considerations

Pathophysiology of asthma

Overview of drugs for asthma

Administering drugs by inhalation

Metered-dose inhalers

Impact of a spacer device on the distribution of inhaled medication.

Impact of a spacer device on the distribution of inhaled medication.

Note that, when a spacer is used, more medication reaches its site of action in the lungs, and less is deposited in the mouth and throat.

Anti-inflammatory drugs

Glucocorticoids

Mechanism of antiasthma action

Adverse effects

Oral glucocorticoids.

Preparations, dosage, and administration

Inhaled glucocorticoids.

Dosage

Drug

Formulation

Adults

Children

Beclomethasone dipropionate

[QVAR]

MDI: 40 or 80 mcg/puff

40–320 mcg twice daily

40–80 mcg twice daily (5–11 yr)

Budesonide

[Pulmicort Flexhaler]

DPI: 90 or 180 mcg/inhalation

360–720 mcg twice daily

180–360 mcg twice daily (6–17 yr)

[Pulmicort Respules]

Suspension for nebulization

250–500 mcg once or twice daily or 1000 mcg once daily

500–1000 mcg/day (1–8 yr)

Ciclesonide

[Alvesco]

MDI: 80 or 160 mcg/puff

80–320 mcg twice daily

80–320 mcg twice daily (12 yr and up)

Flunisolide

[AeroSpan]

MDI: 80 mcg/puff

160–320 mcg twice daily

80–320 mcg twice daily (6–11 yr)

Fluticasone propionate

[Flovent HFA]

MDI: 44, 110, or 220 mcg/puff

88–440 mcg twice daily

88 mcg twice daily (4–11 yr)

[Flovent Diskus]

DPI: 50, 100, or 250 mcg/puff

100–1000 mcg twice daily

50–100 mcg twice daily (4–11 yr)

Mometasone furoate

[Asmanex Twisthaler]

DPI: 110 or 220 mcg/puff

220–440 mcg once or twice daily

110 mcg once daily (4–11 yr)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Drugs for asthma

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access