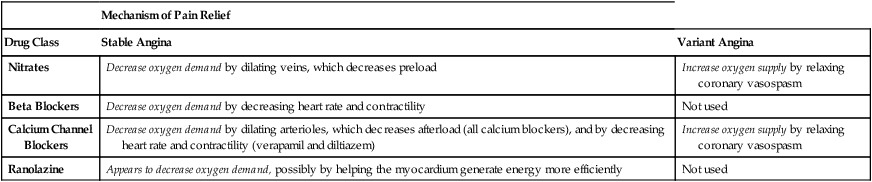

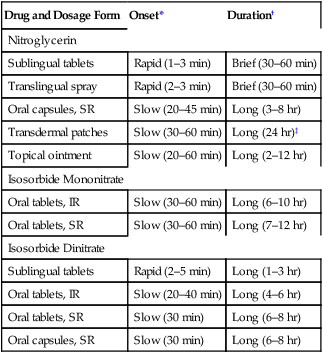

CHAPTER 51 Drug therapy of angina has two goals: (1) prevention of myocardial infarction (MI) and death and (2) prevention of myocardial ischemia and anginal pain. Two types of drugs are employed to decrease the risk of MI and death: cholesterol-lowering drugs and antiplatelet drugs. These agents are discussed in Chapters 50 and 52, respectively. The principal determinants of cardiac oxygen demand are heart rate, myocardial contractility, and, most importantly, intramyocardial wall tension. Wall tension is determined by two factors: cardiac preload and cardiac afterload. (Preload and afterload are defined in Chapter 43.) In summary, cardiac oxygen demand is determined by (1) heart rate, (2) contractility, (3) preload, and (4) afterload. Drugs that reduce these factors reduce oxygen demand. The impact of CAD on the balance between myocardial oxygen demand and oxygen supply is illustrated in Figure 51–1. As depicted, in both the healthy heart and the heart with CAD, oxygen supply and oxygen demand are in balance during rest. (In the presence of CAD, resting oxygen demand is met through dilation of arterioles distal to the partial occlusion. This dilation reduces resistance to blood flow and thereby compensates for the increase in resistance created by plaque.) Stable angina can be treated with three main types of drugs: organic nitrates, beta blockers, and calcium channel blockers. As noted above, ranolazine can be combined with these drugs for additional benefit. All four groups relieve the pain of stable angina primarily by decreasing cardiac oxygen demand (Table 51–1). Please note that drugs only provide symptomatic relief; they do not affect the underlying pathology. To reduce the risk of MI, all patients should receive an antiplatelet drug (eg, aspirin) unless it is contraindicated. Other measures to reduce the risk of infarction are discussed later under Drugs Used to Prevent Myocardial Infarction and Death. TABLE 51–1 Mechanisms of Antianginal Action Risk factors for stable angina should be corrected. Important among these are smoking, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a sedentary lifestyle. Patients should be strongly encouraged to quit smoking. Overweight patients should be given a restricted-calorie diet; the diet should be low in saturated fats (less than 7% of total caloric intake), and total fat content should not exceed 30% of caloric intake. The target weight is 110% of ideal or less. Patients with a sedentary lifestyle should be encouraged to establish a regular program of aerobic exercise (eg, walking, jogging, swimming, biking). Hypertension and hyperlipidemia are major risk factors and should be treated. These disorders are discussed in Chapters 47 and 50, respectively. The biochemical events that lead to vasodilation are outlined in Figure 51–2. The process begins with uptake of nitrate by VSM, followed by conversion of nitrate to its active form: nitric oxide. As indicated, conversion requires the presence of sulfhydryl groups. Nitric oxide then activates guanylyl cyclase, an enzyme that catalyzes the formation of cyclic GMP (cGMP). Through a series of reactions, elevation of cGMP leads to dephosphorylation of light-chain myosin in VSM. (Recall that, in all muscles, phosphorylated myosin interacts with actin to produce contraction.) As a result of dephosphorylation, myosin is unable to interact with actin, and hence VSM relaxes, causing vasodilation. For our purposes, the most important aspect of this sequence is the conversion of nitrate to its active form—nitric oxide—in the presence of a sulfhydryl source. As discussed in Chapter 66, PDE5 inhibitors—sildenafil [Viagra], tadalafil [Cialis], and vardenafil [Levitra]—are used for erectile dysfunction. All three drugs can greatly intensify nitroglycerin-induced vasodilation. Life-threatening hypotension can result. Accordingly, concurrent use of PDE5 inhibitors with nitroglycerin is absolutely contraindicated. All nitroglycerin preparations produce qualitatively similar responses; differences relate only to onset and duration of action (Table 51–2). With two preparations, effects begin rapidly (in 1 to 5 minutes) and then fade in less than 1 hour. With three others, effects begin slowly but last several hours. Only one preparation—sublingual tablets—has both a rapid onset and long duration. TABLE 51–2 Organic Nitrates: Time Course of Action IR = immediate release, SR = sustained release. *Nitrates with a rapid onset have two uses: (1) termination of an ongoing anginal attack and (2) short-term prophylaxis prior to anticipated exertion. Of the rapid-acting nitrates, nitroglycerin (sublingual tablet or translingual spray) is preferred to the others for terminating an ongoing attack. †Long-acting nitrates are used for sustained prophylaxis (prevention) of anginal attacks. All cause tolerance if used without interruption. ‡Although patches can release nitroglycerin for up to 24 hours, they should be removed after 12 to 14 hours to avoid tolerance. Trade names and dosages for nitroglycerin preparations are summarized in Table 51–3. TABLE 51–3 Organic Nitrates: Trade Names and Dosages

Drugs for angina pectoris

Determinants of cardiac oxygen demand and oxygen supply

Oxygen demand.

Angina pectoris: pathophysiology and treatment strategy

Chronic stable angina (exertional angina)

Pathophysiology.

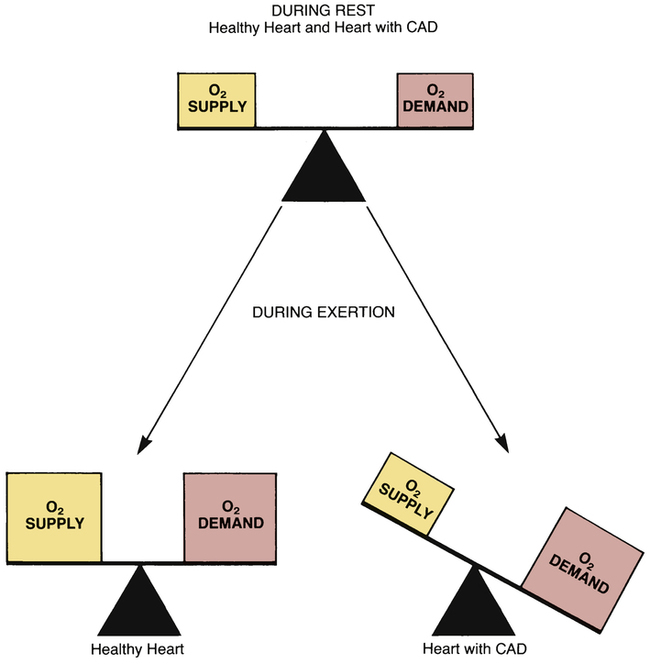

Effect of exertion on the balance between oxygen supply and oxygen demand in the healthy heart and the heart with CAD.

Effect of exertion on the balance between oxygen supply and oxygen demand in the healthy heart and the heart with CAD.

In the healthy heart, O2 supply and O2 demand are always in balance; during exertion, coronary arteries dilate, producing an increase in blood flow to meet the increase in O2 demand. In the heart with CAD, O2 supply and O2 demand are in balance only during rest. During exertion, dilation of coronary arteries cannot compensate for the increase in O2 demand, and an imbalance results.

Overview of therapeutic agents.

Mechanism of Pain Relief

Drug Class

Stable Angina

Variant Angina

Nitrates

Decrease oxygen demand by dilating veins, which decreases preload

Increase oxygen supply by relaxing coronary vasospasm

Beta Blockers

Decrease oxygen demand by decreasing heart rate and contractility

Not used

Calcium Channel Blockers

Decrease oxygen demand by dilating arterioles, which decreases afterload (all calcium blockers), and by decreasing heart rate and contractility (verapamil and diltiazem)

Increase oxygen supply by relaxing coronary vasospasm

Ranolazine

Appears to decrease oxygen demand, possibly by helping the myocardium generate energy more efficiently

Not used

Nondrug therapy.

Organic nitrates

Nitroglycerin

Vasodilator actions

Drug interactions

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors.

Preparations and routes of administration

Drug and Dosage Form

Onset*

Duration†

Nitroglycerin

Sublingual tablets

Rapid (1–3 min)

Brief (30–60 min)

Translingual spray

Rapid (2–3 min)

Brief (30–60 min)

Oral capsules, SR

Slow (20–45 min)

Long (3–8 hr)

Transdermal patches

Slow (30–60 min)

Long (24 hr)‡

Topical ointment

Slow (20–60 min)

Long (2–12 hr)

Isosorbide Mononitrate

Oral tablets, IR

Slow (30–60 min)

Long (6–10 hr)

Oral tablets, SR

Slow (30–60 min)

Long (7–12 hr)

Isosorbide Dinitrate

Sublingual tablets

Rapid (2–5 min)

Long (1–3 hr)

Oral tablets, IR

Slow (20–40 min)

Long (4–6 hr)

Oral tablets, SR

Slow (30 min)

Long (6–8 hr)

Oral capsules, SR

Slow (30 min)

Long (6–8 hr)

Drug and Formulation

Trade Name

Usual Dosage

Nitroglycerin

Sublingual tablets

Nitrostat

0.3–0.6 mg as needed

Translingual spray

Nitrolingual Pumpspray, NitroMist

1–2 sprays (up to 3 sprays in a 15-min period)

Oral capsules, SR

Nitro-Time

2.5–6.5 mg 3 or 4 times daily; to avoid tolerance, administer only once or twice daily; do not crush or chew

Transdermal patches

Minitran, Nitro-Dur, Transderm Nitro ![]() , Trinipatch

, Trinipatch![]()

1 patch a day; to avoid tolerance, remove after 12–14 hr, allowing 10–12 patch-free hours each day. Patches come in sizes that release 0.1–0.8 mg/hr

Topical ointment

Nitro-Bid

1–2 inches (7.5–40 mg) every 4–8 hr

Intravenous

Generic only

5 mcg/min initially, then increased gradually as needed (max 200 mcg/min); tolerance develops with prolonged continuous infusion

Isosorbide Mononitrate

Oral tablets, IR

ISMO, Monoket

20 mg twice daily; to avoid tolerance, take the first dose upon awakening and the second dose 7 hr later

Oral tablets, SR

Imdur

60–240 mg once a day; do not crush or chew

Isosorbide Dinitrate

Sublingual tablets

Generic only

2.5–15 mg every 4–6 hr; do not crush or chew

Oral tablets, IR

Isordil Titradose

5–80 mg every 6 hr; to avoid tolerance, take only 2 or 3 times daily, with the last dose no later than 7:00 pm

Oral tablets, SR

Generic only

40 mg every 6–12 hr; to avoid tolerance, take only once or twice daily (at 8:00 am and 2:00 pm)

Oral capsules, SR

Dilatrate-SR

40 mg every 6–12 hr; to avoid tolerance, take only once or twice daily (at 8:00 am and 2:00 pm)

Amyl Nitrite

Inhalant

Generic only

0.18 or 0.3 mL ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree