Discuss the etiology and pathophysiology of depression and bipolar disorder.

Describe the major features of various mood disorders.

Describe the major features of various mood disorders.

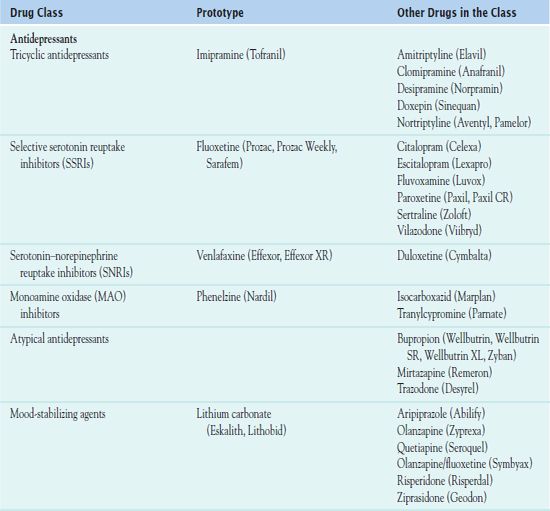

Compare and contrast the different categories of antidepressants: tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, mixed serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other atypical antidepressants.

Compare and contrast the different categories of antidepressants: tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, mixed serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and other atypical antidepressants.

Discuss the drugs used to treat depression in terms of prototype, action, indications for use, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Discuss the drugs used to treat depression in terms of prototype, action, indications for use, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Discuss the drugs used to treat bipolar disorder in terms of prototype, action, indications for use, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Discuss the drugs used to treat bipolar disorder in terms of prototype, action, indications for use, adverse effects, and nursing implications.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for mood disorders.

Implement the nursing process in the care of patients undergoing drug therapy for mood disorders.

Clinical Application Case Study

While in the hospital, Carl Mehring, a 70-year-old man, receives a diagnosis of chronic depression secondary to chronic heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and renal insufficiency. As his health has declined, so has his interest in his family, friends, and hobbies. His physician prescribes sertraline 50 mg orally at bedtime.

KEY TERMS

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome: condition that occurs with sudden termination of most antidepressant drugs; typical symptoms may occur more rapidly and may be more intense with drugs that have a short half-life and/or are used for long periods

Bipolar disorder: mood disorder characterized by episodes of depression alternating with episodes of mania

Cyclothymia: mild type of bipolar disorder involving periods of hypomania and depression that do not meet the criteria for mania and major depression

Depression: most common mental illness, which is characterized by depressed mood, feelings of sadness, or emotional upset; occurs in people of all ages

Dysthymia: chronically depressed mood and at least two other symptoms of depression for 2 years

Enuresis: bedwetting or involuntary urination resulting from a physical or psychological disorder

Hypomania: persistent irritable mood but absence of psychotic symptoms characteristic of true mania

Mania: emotional disorder characterized by euphoria or irritability; usually occurs in bipolar disorder

Postnatal depression: major depressive episode occurring after the birth of a child

Seasonal affective disorder: depressive episode occurring in a certain season, usually the winter

Serotonin syndrome: serious and sometimes fatal reaction due to combined therapy with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor and a monoamine oxidase inhibitor or another drug that potentiates serotonin neurotransmission

Introduction

Mood disorders include depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, and cyclothymia (Box 54.1). Major depressive disorder is relatively common in adults, and it also occurs in children and adolescents. This chapter focuses on depression and antidepressant drugs as well as bipolar disorder and mood-stabilizing drugs.

BOX 54.1 Types and Symptoms of Mood Disorders

Depression

Depression, often described as the most common mental illness, is characterized by depressed mood, feelings of sadness, or emotional upset, and it occurs in all age groups. Mild depression occurs in everyone as a normal response to life stresses and losses and usually does not require treatment; severe or major depression is a psychiatric illness and requires treatment. Major depression also is categorized as unipolar, in which people of usually normal moods experience recurrent episodes of depression.

Major Depression

The American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV), lists criteria for a major depressive episode as a depressed mood plus at least five of the following symptoms for at least 2 weeks:

Loss of energy, fatigue

Loss of energy, fatigue

Indecisiveness

Indecisiveness

Difficulty thinking and concentrating

Difficulty thinking and concentrating

Loss of interest in appearance, work, and leisure and sexual activities

Loss of interest in appearance, work, and leisure and sexual activities

Inappropriate feelings of guilt and worthlessness

Inappropriate feelings of guilt and worthlessness

Loss of appetite and weight loss, or excessive eating and weight gain

Loss of appetite and weight loss, or excessive eating and weight gain

Sleep disorders (hypersomnia or insomnia)

Sleep disorders (hypersomnia or insomnia)

Somatic symptoms (e.g., constipation, headache, atypical pain)

Somatic symptoms (e.g., constipation, headache, atypical pain)

Obsession with death or thoughts of suicide

Obsession with death or thoughts of suicide

Psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions

Psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions

Subtypes of depression recognized by the DSM-IV as “specifier” include

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which occurs during winter months, particularly in areas where there is a short period of natural sunlight. The person does not manifest a depressed mood during season of sunlight. The depression is thought to be associated with the decreased release of the neurohormone melatonin. SAD resolves in the spring, and treatment involves light therapy, antidepressants, and specifically timing the administration of melatonin.

Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which occurs during winter months, particularly in areas where there is a short period of natural sunlight. The person does not manifest a depressed mood during season of sunlight. The depression is thought to be associated with the decreased release of the neurohormone melatonin. SAD resolves in the spring, and treatment involves light therapy, antidepressants, and specifically timing the administration of melatonin.

Postnatal depression is defined as a depressive episode occurring within 1 to 6 months after delivery. Postnatal depression is common, affecting 12% to 15% of new mothers. For women with a history of postnatal depression, the risk of recurrence is 33%, and suicide is the main cause of maternal death within the first year of childbirth. Postnatal depression may resolve without treatment within 3 to 6 months; however, 25% of affected mothers will still be depressed 1 year after delivery. Treatment generally involves the use of psychotherapy and/or antidepressants; however, there is limited information available to guide the selection of the most efficacious antidepressants for treatment of postnatal depression.

Postnatal depression is defined as a depressive episode occurring within 1 to 6 months after delivery. Postnatal depression is common, affecting 12% to 15% of new mothers. For women with a history of postnatal depression, the risk of recurrence is 33%, and suicide is the main cause of maternal death within the first year of childbirth. Postnatal depression may resolve without treatment within 3 to 6 months; however, 25% of affected mothers will still be depressed 1 year after delivery. Treatment generally involves the use of psychotherapy and/or antidepressants; however, there is limited information available to guide the selection of the most efficacious antidepressants for treatment of postnatal depression.

Dysthymia

Dysthymia involves a chronically depressed mood and at least two other symptoms (e.g., anorexia, overeating, insomnia, hypersomnia, low energy, low self-esteem, poor concentration, feelings of hopelessness) for 2 years. Although the symptoms may cause significant social- and work-related impairments, they are not severe enough to meet the criteria for major depression.

Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder involves episodes of depression alternating with episodes of mania. Mania is characterized by excessive central nervous system (CNS) stimulation with physical and mental hyperactivity (e.g., agitation, constant talking, constant movement, grandiose ideas, impulsiveness, inflated self-esteem, little need for sleep, poor concentration, racing thoughts, short attention span) for at least 1 week. Symptoms are similar to those of acute psychosis or schizophrenia. Hypomania involves the same symptoms, but they are less severe, indicate less CNS stimulation and hyperactivity, and last 3 or 4 days.

Cyclothymia

Cyclothymia is a mild type of bipolar disorder that involves periods of hypomania and depression that do not meet the criteria for mania and major depression. Symptoms must be present for at least 2 years. It does not usually require drug therapy.

Overview of Depression

Depression is a mood disorder in which feelings of sadness, loss, anger, or frustration interfere with everyday life for several weeks or longer. The condition affects people of all ages. It is difficult to determine the overall incidence of depression in the United States, because only 50% of the people who meet the criteria for depression (see Box 54-1) seek help. Generally, major depression affects women twice as often as men. However, in older adults, at least one major study in older adults demonstrated overall incidence of depression to be the same in men and women (Steffens, Fisher, Langa, Potter, & Plassman, 2009). Depression has no particular racial affinity.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Extensive study has demonstrated that depression results from interactions among several complex factors. Causes involve the immune system, monoamine neurotransmitter dysfunction, and neuroendocrine factors, as well as genetic and environmental factors.

Immune Factors

Immune cells (e.g., T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes) produce cytokines (e.g., interleukins, interferons, tumor necrosis factor), which affect neurotransmission. Possible mechanisms of cytokine-induced depression include increased corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, alteration of monoamine neurotransmitters in several areas of the brain, or cytokines functioning as neurotransmitters and exerting direct effects on brain function.

Monoamine Neurotransmitter Dysfunction

Depression is thought to result from a deficiency of norepinephrine and/or serotonin. This hypothesis has stemmed from studies demonstrating that antidepressant drugs increase the amounts of norepinephrine and/or serotonin in the central nervous system (CNS) synapse by inhibiting their reuptake into the presynaptic neuron. Serotonin helps regulate mood, sleep, appetite, energy level, and cognitive and psychomotor functions, which are disturbed in depression.

Emphasis shifted toward receptors because the neurotransmitter view did not explain why the amounts of neurotransmitter increased within hours after single doses of a drug, but relief of depression occurred only after weeks of drug therapy. Researchers identified desensitization in norepinephrine and serotonin receptors (downregulation) with chronic antidepressant drug therapy. Apparently, long-term administration of antidepressant drugs produces complex changes in the sensitivities of both presynaptic and postsynaptic receptor sites.

Overall, there is increasing awareness that balance, integration, and interactions among norepinephrine, serotonin, and possibly other neurotransmission systems (e.g., dopamine, acetylcholine) are probably more important etiologic factors than single neurotransmitter or receptor alterations.

Neuroendocrine Factors

In addition to monoamine neurotransmission systems, researchers have identified nonmonoamine systems that influence neurotransmission and are significantly altered in depression. A major nonmonoamine is CRF, whose secretion is increased in people with depression. CRF-secreting neurons are widespread in the CNS, and CRF apparently functions as a neurotransmitter and mediator of the endocrine, autonomic, immune, and behavioral responses to stress as well as a releasing factor for corticotropin. The subsequent increase in cortisol by the adrenal cortex (part of the normal physiologic response to stress) is thought to decrease the numbers or sensitivity of cortisol receptors (downregulation) and lead to depression. This alteration of cortisol receptors takes about 2 weeks, the approximate time interval required for the drugs to improve symptoms of depression. Extrahypothalamic CRF is also increased in depression. Secretion of both hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic CRF apparently returns to normal with recovery from depression.

Other Factors

Genetic factors are important because the link between genetics and depression suggests that a close relative of a depressed person is more likely to inherit the disease than the general population. Twin studies support this conclusion.

Environmental factors include stressful life events, such as physical or sexual abuse in childhood, which apparently alter brain structure and function and contribute to the development of depression in some people. Experts have identified changes in CRF, the HPA axis, and the noradrenergic neurotransmission system, which are thought to cause a hypersensitive or exaggerated response to later stressful events, including mild stress or daily life events.

Clinical Manifestations

Box 54.1 outlines the clinical manifestations of depression. Behavioral changes, especially anxiety, agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, irritability, hostility, impulsivity, akathisia, hypomania, and mania, may indicate worsening depression or suicidality.

Drug Therapy

Antidepressant therapy may be indicated if depressive symptoms persist at least 2 weeks, impair social relationships or work performance, and occur independently of life events. Antidepressants are used to regulate mood specifically affecting serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. Antidepressant effects are attributed to changes in receptors rather than changes in neurotransmitters. Although some of the drugs act more selectively on one neurotransmission system than another initially, this selectivity seems to be lost with chronic administration. Drugs used in the pharmacologic management of depressive disorders are derived from several chemical groups. Older antidepressants include the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and the monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors. Newer drugs include the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and several adjuvant atypical antidepressant drugs that differ from TCAs and MAO inhibitors. As the name implies, reuptake inhibitors block the reuptake of certain neurotransmitters (serotonin with the SSRIs and serotonin and norepinephrine with the SNRIs). Table 54.1 lists the drugs used to treat depression.

General characteristics of antidepressants include the following:

• All are effective in relieving depression, but they differ in their adverse effects.

• People must take them for 2 to 4 weeks before depressive symptoms improve

• Administration is oral. Absorbed from the small bowel, they enter the portal circulation and circulate through the liver, where they undergo extensive first-pass metabolism before reaching the systemic circulation.

• Metabolism is by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes in the liver. Thus, antidepressants may interact with each other and with a wide variety of drugs that are normally metabolized by the same subgroups of enzymes. Additionally, there is a documented ethnic variation in response to antidepressants (Box 54.2).

BOX 54.2 Genetic and Ethnic Differences in Response to Antidepressant Drug Therapy

Antidepressant therapy for nonwhite populations in the United States is based primarily on dosage recommendations, pharmacokinetic data, and adverse effects derived from white recipients. However, several studies document differences in drug effects in nonwhite populations mainly attributed to genetic or ethnic variations in the cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme activity of the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. People are poor, intermediate, extensive or ultra fast metabolizers. Although all ethnic groups are genetically heterogeneous and individual members ma’ respond differently, health care providers must consider potential differences in responses to drug therapy.

African Americans may be poor metabolizers and tend to have higher plasma drug levels for a given dose, respond more rapidly, experience a higher incidence of adverse effects, and metabolize tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) more slowly than whites. With lithium, African Americans report more adverse reactions than whites and may need smaller doses.

African Americans may be poor metabolizers and tend to have higher plasma drug levels for a given dose, respond more rapidly, experience a higher incidence of adverse effects, and metabolize tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) more slowly than whites. With lithium, African Americans report more adverse reactions than whites and may need smaller doses.

Asians tend to metabolize antidepressant drugs slowly (poor metabolizers) and therefore have higher plasma drug levels for a given dose than whites. Most studies have used TCAs and a limited number of Asian subgroups. Thus, it cannot be assumed that all antidepressants and all people of Asian heritage respond similarly. With lithium, there are no apparent differences between effects in Asians and whites.

Asians tend to metabolize antidepressant drugs slowly (poor metabolizers) and therefore have higher plasma drug levels for a given dose than whites. Most studies have used TCAs and a limited number of Asian subgroups. Thus, it cannot be assumed that all antidepressants and all people of Asian heritage respond similarly. With lithium, there are no apparent differences between effects in Asians and whites.

Information regarding the reaction of the Hispanic population to antidepressants is largely unknown. Few studies have been performed; some report a need for lower doses of TCAs and greater susceptibility to adverse effects, whereas others report no differences between Hispanics and whites.

Because the available drugs have similar efficacy in treating depression, the choice of an antidepressant depends on the patient’s age; medical condition; previous history of drug response, if any; and the specific drug’s adverse effects. Cost is also a factor to consider. Although the newer drugs are much more expensive than the TCAs, they may be more cost-effective overall because TCAs are more likely to cause serious adverse effects, they require monitoring of plasma drug levels and electrocardiograms (ECGs), and patients are more likely to stop taking them.

It is important to note that sudden termination of most antidepressants results in antidepressant discontinuation syndrome In general, symptoms, which include flu-like symptoms, insomnia, nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances, and hyper-arousal, develop more rapidly and may be more intense with drugs that have a short half-life and/or that are given for long periods. As with other psychotropic drugs, to avoid this syndrome, it is essential to taper the dosage of the antidepressant and discontinue it gradually, over 6 to 8 weeks, unless severe drug toxicity, anaphylactic reaction, or another life-threatening condition is present. The occurrence of withdrawal symptoms may indicate skipped doses or abrupt discontinuation of the drug.

Overview of Bipolar Disorder

Bipolar disorder is a condition in which people alternate between periods of depression and overexcitement. There are two subtypes of this disorder, which are defined by the presentation of the mood disorder. Bipolar disorder type I is characterized by episodes of major depression plus mania (euphoria or irritability) and occurs equally in men and women. Bipolar disorder type II is characterized by episodes of major depression plus episodes of hypomania (persistent irritable mood but absence of euphoria) and occurs more frequently in women. Bipolar spectrum disorder broadens the definition of bipolar disorder to include conditions such as cyclothymia (a mild type of bipolar disorder) and dysthymia (chronically depressed mood). Bipolar disorders may affect an estimated 5% of adults.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Like depression, mania, and hypomania, the hallmarks of bipolar disorder have historically been associated with abnormal functioning of neurotransmitters or receptors, such as a relative excess of excitatory neurotransmitters (e.g., norepinephrine) or a relative deficiency of inhibitory neurotransmitters (e.g., gamma-aminobutyric acid [GABA]). Another more recent proposed etiology for bipolar disorder is alteration in neuronal growth and survival in areas of the brain (e.g., subgenual precortex, hippocampus) involved with mood and memory. Secondary causes of manic and hypomanic behavior include drugs that stimulate the CNS, CNS diseases and infections, and electrolyte or endocrine disorders.

Clinical Manifestations

Bipolar disorder manifests with unpredictable mood swings. In the manic phase, clinical manifestations include excessive happiness and energy, excitement, racing thoughts, restlessness, decreased need for sleep, high sex drive, and a tendency to make grandiose statements and unattainable plans. During a depressive episode, manifestations include sadness, lack of energy, increased need for sleep, uncontrollable crying, changes in appetite, and thoughts of suicide. Box 54.1 outlines additional symptoms.

Drug Therapy

Research has shown that mood-stabilizing drugs such as lithium stimulate neuronal growth and reduce brain atrophy in people with long-standing mood disorders. Table 54.1 lists some mood-stabilizing drugs.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

TCAs are the oldest antidepressants, although they are now second-line drugs for the treatment of depression.  Imipramine (Tofranil) is the prototype. A patient’s previous response or susceptibility to adverse effects may be the basis for initial selection of TCAs. For example, if a patient (or a close family member) once responded well to a particular drug, that drug is probably the drug of choice for repeated episodes of depression. The response of family members to individual drugs may be significant because there is a strong genetic component to depression and drug response. If therapeutic effects do not occur within 4 weeks, it is probably necessary to discontinue or change the TCA, because some patients tolerate or respond better to one TCA than to another. For patients with suicidal tendencies, beginning an SSRI or another newer drug is preferred over a TCA due to the safety profile.

Imipramine (Tofranil) is the prototype. A patient’s previous response or susceptibility to adverse effects may be the basis for initial selection of TCAs. For example, if a patient (or a close family member) once responded well to a particular drug, that drug is probably the drug of choice for repeated episodes of depression. The response of family members to individual drugs may be significant because there is a strong genetic component to depression and drug response. If therapeutic effects do not occur within 4 weeks, it is probably necessary to discontinue or change the TCA, because some patients tolerate or respond better to one TCA than to another. For patients with suicidal tendencies, beginning an SSRI or another newer drug is preferred over a TCA due to the safety profile.

Pharmacokinetics

Imipramine is well absorbed after oral administration, and the drug is widely distributed in body tissues. Peak levels occur in 1 to 2 hours, and the duration of action is unknown. Its half-life is 8 to 16 hours. Imipramine is metabolized in the liver by CYP2D6 enzymes to active and inactive metabolites, and it is excreted primarily by the kidneys

Action

Imipramine blocks the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin at the presynaptic nerve endings, increasing the action of both neurotransmitters. The drug’s use in enuresis may be due to the fact that imipramine also blocks acetylcholine receptors.

Use

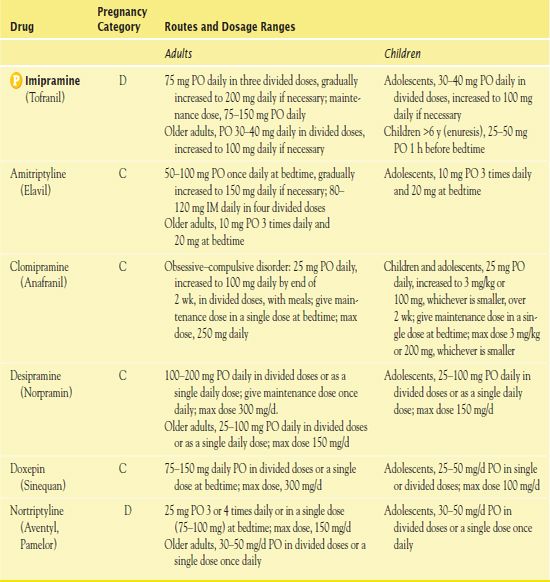

Imipramine may be useful in the treatment of depression. Prescribers may order it for children and adolescents in the management of enuresis (bedwetting or involuntary urination resulting from a physical or psychological disorder) after physical causes (e.g., urethral irritation, excessive intake of fluids) have been ruled out. Table 54.2 contains route and dosage information for imipramine and the other TCAs.

TABLE 54.2

TABLE 54.2

Use in Children

Imipramine or other TCAs are probably not the drugs of first choice for adolescents because TCAs are more toxic in overdose than other antidepressants, and suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescents. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a BLACK BOX WARNING ♦ alerting health care providers to the increased risk of suicidal ideation in children, adolescents, and young adults 18 to 24 years of age who are taking antidepressants, including imipramine.

Use in Older Adults

Imipramine may cause or aggravate conditions common in older adults (e.g., cardiac conduction abnormalities, urinary retention, narrow-angle glaucoma). In addition, impaired compensatory mechanisms make older adults more likely to experience anticholinergic effects, confusion, orthostatic hypotension, and sedation. It is important to monitor vital signs, serum drug levels, and ECGs regularly.

Use in Patients With Hepatic Impairment

Hepatic impairment leads to higher plasma levels of imipramine. Thus, caution is necessary in patients with severe liver impairment.

Outpatient Care of Young People after Emergency Treatment of Deliberate Self-Harm

by J. A. BRIDGE, S. C. MARCUS, & M. OLFSON

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2012, 51(2), 213–222

The authors completed a national retrospective longitudinal cohort analysis of Medicaid-extracted data for children and adolescents 10 to 19 years of age who presented to emergency departments after deliberate self-harm. They concluded that deliberate self-harm is the most common reason for an emergency department visit for people of this age and that nearly 90% of children and adolescents who deliberately harm themselves meet diagnostic criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder, usually related to mood. Also, they established that in this population, most children and adolescents who presented to emergency departments with deliberate self-harm were discharged to the community and did not receive inpatient care. Although some of these people could be low-risk patients, the researchers highlighted that deliberate self-harm is the major risk factor for suicide and that the greatest risk for suicide was immediately after a self-harm episode. Their findings indicated that staffing patterns and evaluation protocols may influence the decision to complete a mental health assessment in the emergency department more than the clinical characteristics of patients seeking help for a deliberate self-harm event.

IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE: Nursing staff play a strategic role in influencing arrangements for a mental health assessment in the emergency department for all patients presenting with deliberate self-harm. Established evaluation protocols should include a mental health assessment with necessary referral for those at any age who inflict intentional self-harm. Identifying high-risk people who may commit suicide and providing appropriate mental health services can enhance suicide prevention.

Use in Patients With Critical Illness

Adverse effects common with imipramine use (e.g., confusion, dysrhythmias, tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, urinary retention) are a concern and may further compromise patients who are critically ill. Antidepressants, including imipramine, warrant very cautious use perioperatively because of the risk of serious adverse effects and interactions with anesthetics and other commonly used drugs. It is necessary to discontinue imipramine several days before elective surgery and resume it several days after surgery.

Use in Patients Receiving Home Care

The nurse who sees a patient taking imipramine in the home setting should assess him or her for improvement of symptoms, appropriate administration of the drug, and management of adverse effects, particularly safety factors. A nurse visiting the home for other reasons should observe for signs of depression; health concerns may precipitate symptoms.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects of imipramine include sedation, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac dysrhythmias, anticholinergic symptoms (e.g., blurred vision, dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention), and weight gain. Symptoms of TCA overdose occur 1 to 4 hours after drug ingestion. They consist primarily of CNS depression and cardiovascular effects (e.g., nystagmus, tremor, restlessness, seizures, hypotension, dysrhythmias, myocardial depression). Death usually results from cardiac, respiratory, and circulatory failure.

TCAs are associated with clearly defined withdrawal syndromes, and these drugs also have strong anticholinergic effects. When they are abruptly discontinued, cholinergic rebound may occur. Symptoms include hypersalivation, diarrhea, urinary urgency, abdominal cramping, and sweating.

Contraindications

Contraindications to impramine include known sensitivity to the drug and immediately post-acute myocardial infarction.

Nursing Implications

Preventing Interactions

Several drugs interact with imipramine. The drug may inhibit the metabolism of other drugs, including antidepressants, phenothiazines, carbamazepine, flecainide, and propafenone. The use of imipramine and MAO inhibitors concurrently may have serious effects, including severe seizures and death. Alcohol may increase the sedative effects of imipramine. The herb St. John’s wort may reduce the blood levels of imipramine and other TCAs.

Administering the Medication

People should take imipramine at bedtime to aid sleep and decrease daytime sedation. Overall, with TCAs, it is best to begin with small doses, which are increased to the desired dose over 1 to 2 weeks. Administration once or twice daily is possible because the drug has a long elimination half-life. Measurement of plasma levels is helpful in adjusting dosages.

Assessing for Therapeutic Effects

The nurse is aware of patient statements about feeling better or less depressed. He or she observes for increased appetite, physical activity, and interest in surroundings; improved sleep patterns; improved appearance; decreased anxiety; and decreased somatic complaints. Mood elevation may take 2 to 3 weeks.

Assessing for Adverse Effects

The nurse observes for CNS effects, gastrointestinal (GI) effects, cardiovascular effects, and other effects. Because imipramine may have adverse effects on the heart, especially in overdose, experts recommend baseline and follow-up ECGs for all patients. In addition, it is important to assess for suicidal thoughts or plans, especially at the beginning of therapy or when dosages are increased or decreased.

Patient Teaching

Box 54.3 presents patient teaching guidelines for the antidepressants, including the TCAs.

BOX 54.3  Patient Teaching Guidelines for Antidepressants

Patient Teaching Guidelines for Antidepressants

General Considerations

Take antidepressants as directed to maximize therapeutic benefits and minimize adverse effects. Do not alter doses when symptoms subside. Antidepressants are usually given for several months, perhaps years.

Take antidepressants as directed to maximize therapeutic benefits and minimize adverse effects. Do not alter doses when symptoms subside. Antidepressants are usually given for several months, perhaps years.

Therapeutic effects (relief of symptoms) may not occur for 2 to 4 weeks after drug therapy is started. As a result, it is very important not to think the drug is ineffective and stop taking it prematurely. Continue to take the drug even if you feel better to prevent the return of depression

Therapeutic effects (relief of symptoms) may not occur for 2 to 4 weeks after drug therapy is started. As a result, it is very important not to think the drug is ineffective and stop taking it prematurely. Continue to take the drug even if you feel better to prevent the return of depression

Do not take other prescription or over-the-counter drugs, including cold remedies, without consulting a health care provider. Potentially serious drug interactions may occur.

Do not take other prescription or over-the-counter drugs, including cold remedies, without consulting a health care provider. Potentially serious drug interactions may occur.

Do not take the herbal supplement St. John’s wort while taking a prescription antidepressant. Serious interactions may occur.

Do not take the herbal supplement St. John’s wort while taking a prescription antidepressant. Serious interactions may occur.

Inform any physician, surgeon, dentist, or nurse practitioner about the antidepressants being taken. Potentially serious adverse effects or drug interactions may occur if certain other drugs are prescribed.

Inform any physician, surgeon, dentist, or nurse practitioner about the antidepressants being taken. Potentially serious adverse effects or drug interactions may occur if certain other drugs are prescribed.

Avoid activities that require alertness and physical coordination (e.g., driving a car, operating other machinery) until reasonably sure the medication does not make you drowsy or impair your ability to perform the activities safely.

Avoid activities that require alertness and physical coordination (e.g., driving a car, operating other machinery) until reasonably sure the medication does not make you drowsy or impair your ability to perform the activities safely.

Avoid alcohol and other central nervous system depressants (e.g., any drugs that cause drowsiness). Excessive drowsiness, dizziness, difficulty breathing, and low blood pressure may occur, with potentially serious consequences.

Avoid alcohol and other central nervous system depressants (e.g., any drugs that cause drowsiness). Excessive drowsiness, dizziness, difficulty breathing, and low blood pressure may occur, with potentially serious consequences.

Learn the name and type of the prescribed antidepressant to help avoid undesirable interactions with other drugs or a physician prescribing other drugs with similar effects. There are several different types of antidepressants, with different characteristics and precautions for safe and effective usage.

Learn the name and type of the prescribed antidepressant to help avoid undesirable interactions with other drugs or a physician prescribing other drugs with similar effects. There are several different types of antidepressants, with different characteristics and precautions for safe and effective usage.

Do not stop taking any antidepressant without discussing it with a health care provider. If a problem occurs, the type of drug, the dose, or other aspects may be changed to solve the problem and allow continued use of the medication.

Do not stop taking any antidepressant without discussing it with a health care provider. If a problem occurs, the type of drug, the dose, or other aspects may be changed to solve the problem and allow continued use of the medication.

Counseling, support groups, relaxation techniques, and other nonmedication treatments are recommended along with drug therapy.

Counseling, support groups, relaxation techniques, and other nonmedication treatments are recommended along with drug therapy.

Notify your physician if you become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy with antidepressants.

Notify your physician if you become pregnant or intend to become pregnant during therapy with antidepressants.

Self- or Caregiver Administration

With a tricyclic antidepressant (e.g., amitriptyline), take at bedtime to aid sleep and decrease adverse effects. Also, report urinary retention, fainting, irregular heartbeat, seizures, restlessness, and mental confusion. These are potentially serious adverse drug effects.

With a tricyclic antidepressant (e.g., amitriptyline), take at bedtime to aid sleep and decrease adverse effects. Also, report urinary retention, fainting, irregular heartbeat, seizures, restlessness, and mental confusion. These are potentially serious adverse drug effects.

With a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, take the drug in the morning because it may interfere with sleep if taken at bedtime.

With a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, take the drug in the morning because it may interfere with sleep if taken at bedtime.

In addition, notify a health care provider if a skin rash or other allergic reaction occurs. Allergic reactions are uncommon but may require that the drug be discontinued.

In addition, notify a health care provider if a skin rash or other allergic reaction occurs. Allergic reactions are uncommon but may require that the drug be discontinued.

Recognize the importance of follow-up and seeking professional help for the signs of dizziness or insomnia or other symptoms that negatively affect your life.

Recognize the importance of follow-up and seeking professional help for the signs of dizziness or insomnia or other symptoms that negatively affect your life.

Realize that escitalopram (Lexapro) is a derivative of citalopram (Celexa). The two medications should not be taken concomitantly.

Realize that escitalopram (Lexapro) is a derivative of citalopram (Celexa). The two medications should not be taken concomitantly.

With venlafaxine (Effexor), take as directed or ask for instructions. This drug is often taken twice daily. Notify a health care provider if a skin rash or other allergic reaction occurs. An allergic reaction may require that the drug be discontinued.

With venlafaxine (Effexor), take as directed or ask for instructions. This drug is often taken twice daily. Notify a health care provider if a skin rash or other allergic reaction occurs. An allergic reaction may require that the drug be discontinued.

With venlafaxine, use effective birth control methods while taking this drug. Pregnancy is a contraindication.

With venlafaxine, use effective birth control methods while taking this drug. Pregnancy is a contraindication.

With duloxetine and desvenlafaxine, swallow the medication whole, do not crush, chew, or sprinkle capsule contents on food.

With duloxetine and desvenlafaxine, swallow the medication whole, do not crush, chew, or sprinkle capsule contents on food.

With phenelzine and other monoamine oxidase inhibitors, foods that contain tyramine or tyrosine may have to be avoided altogether to prevent the risk of hypertensive crisis. This includes aged cheeses, coffee, chocolate, wine, bananas, avocados, fava beans, and most fermented and pickled foods.

With phenelzine and other monoamine oxidase inhibitors, foods that contain tyramine or tyrosine may have to be avoided altogether to prevent the risk of hypertensive crisis. This includes aged cheeses, coffee, chocolate, wine, bananas, avocados, fava beans, and most fermented and pickled foods.

Bupropion is a unique drug prescribed for depression (brand name, Wellbutrin) and for smoking cessation (brand name, Zyban). It is extremely important not to increase the dose or take the two brand names at the same time (as might happen with different physicians or filling prescriptions at different pharmacies). Overdoses may cause seizures as well as other adverse effects. When used for smoking cessation, Zyban is recommended for up to 12 weeks if progress is being made. If significant progress is not made by approximately 7 weeks, it is considered unlikely that longer drug use will be helpful.

Bupropion is a unique drug prescribed for depression (brand name, Wellbutrin) and for smoking cessation (brand name, Zyban). It is extremely important not to increase the dose or take the two brand names at the same time (as might happen with different physicians or filling prescriptions at different pharmacies). Overdoses may cause seizures as well as other adverse effects. When used for smoking cessation, Zyban is recommended for up to 12 weeks if progress is being made. If significant progress is not made by approximately 7 weeks, it is considered unlikely that longer drug use will be helpful.

There are short-, intermediate-, and long-acting forms of bupropion that are taken three times, two times, or one time per day, respectively. Be sure to take your medication as prescribed by your physician.

There are short-, intermediate-, and long-acting forms of bupropion that are taken three times, two times, or one time per day, respectively. Be sure to take your medication as prescribed by your physician.

Make sure that you and the people you live with are familiar with the signs and symptoms of worsening depression and know how to seek help for signs of overdose.

Make sure that you and the people you live with are familiar with the signs and symptoms of worsening depression and know how to seek help for signs of overdose.