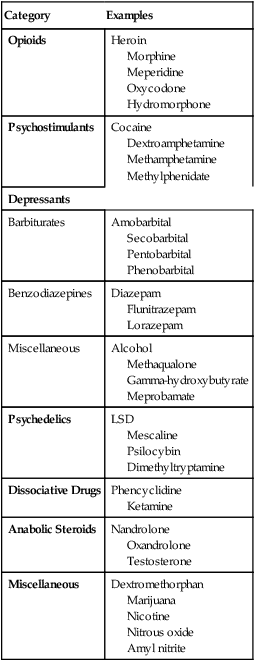

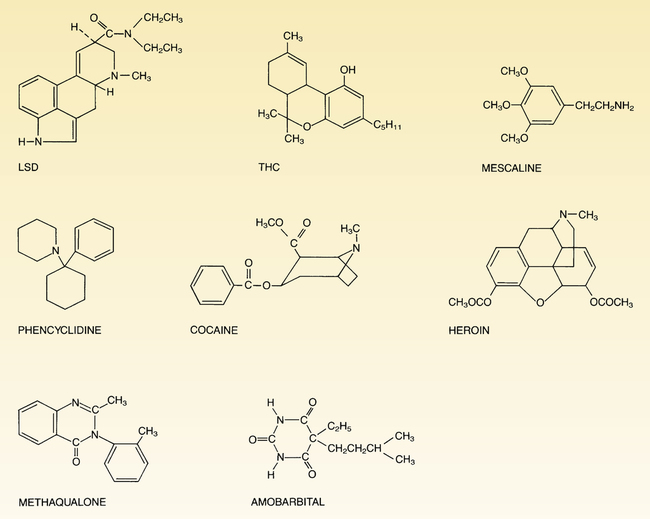

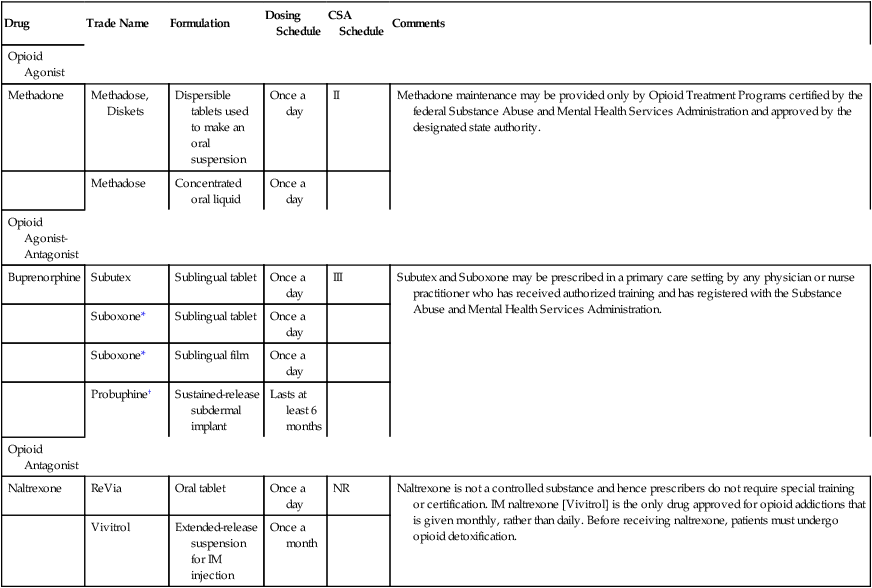

CHAPTER 40 In this chapter, we discuss all of the major drugs of abuse except alcohol (Chapter 38) and nicotine and tobacco (Chapter 39). As indicated in Table 40–1, abused drugs fall into seven major categories: (1) opioids, (2) psychostimulants, (3) depressants, (4) psychedelics, (5) dissociative drugs, (6) anabolic steroids, and (7) miscellaneous drugs of abuse. The basic pharmacology of many of these drugs is presented in previous chapters, and hence their discussion here is brief. Agents that have not been addressed previously (eg, marijuana, d-lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD]) are discussed in depth. Structural formulas of representative controlled substances are shown in Figure 40–1. Street names for abused drugs are given in Table 40–2. TABLE 40–1 Pharmacologic Categorization of Abused Drugs TABLE 40–2 Some Street Names for Abused Drugs The opioids (eg, heroin, oxycodone, meperidine) are major drugs of abuse. As a result, most opioids are classified as Schedule II substances. The basic pharmacology of the opioids is discussed in Chapter 28. In an effort to reduce OxyContin abuse, the controlled-release tablets were reformulated in 2010. The new formulation bears the imprint OP, rather than OC, which appeared on the old formulation. Compared with the old tablets, OxyContin OP tablets are much harder to crush into a powder. And if exposed to water or alcohol, the tablets just form a gummy blob, rather than a solution that can be drawn into a syringe and injected. However, there is no evidence that OxyContin OP tablets are less subject to abuse, diversion, overdose, or addiction than the old tablets. As noted in Chapter 28, oxycodone is also available in a tamper resistant immediate-release formulation, sold as Oxecta. Treatment of acute opioid toxicity is discussed at length in Chapter 28 and summarized here. Overdose produces a classic triad of symptoms: respiratory depression, coma, and pinpoint pupils. Naloxone [Narcan], an opioid antagonist, is the treatment of choice. This agent rapidly reverses all signs of opioid poisoning. However, dosage must be titrated carefully. Why? Because if too much is given, the addict will swing from a state of intoxication to one of withdrawal. Owing to its short half-life, naloxone must be re-administered every few hours until opioid concentrations have dropped to nontoxic levels, which may take days. Failure to repeat naloxone dosing may result in the death of patients who had earlier been rendered symptom free. Three kinds of drugs are employed for long-term management: opioid agonists, opioid agonist-antagonists, and opioid antagonists. Opioid agonists (methadone) and agonist-antagonists (buprenorphine) substitute for the abused opioid and are given to patients who are not yet ready for detoxification. In contrast, opioid antagonists (naltrexone) are used to discourage renewed opioid use after detoxification has been accomplished. Drugs used for long-term management of opioid addiction are summarized in Table 40–3. TABLE 40–3 Drugs for Long-Term Management of Opioid Addiction CSA = Controlled Substances Act, NR = not regulated under the CSA. *In addition to buprenorphine, Suboxone contains naloxone, an opioid antagonist, to discourage IV dosing. Buprenorphine [Subutex, Suboxone], an agonist-antagonist opioid, was approved for treating addiction in 2002. As discussed in Chapter 28, the drug is a partial agonist at mu receptors and a full antagonist at kappa receptors. Buprenorphine can be used for maintenance therapy and to facilitate detoxification (see above). When used for maintenance, buprenorphine alleviates craving, reduces use of illicit opioids, and increases retention in therapeutic programs. The basic pharmacology of buprenorphine is presented in Chapter 28. The family of CNS depressants consists of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, alcohol, and other agents. With the exception of the benzodiazepines, all of these drugs are more alike than different. The benzodiazepines have properties that set them apart. The basic pharmacology of the benzodiazepines, barbiturates, and most other CNS depressants is presented in Chapter 34; the pharmacology of alcohol is presented in Chapter 38. Discussion here is limited to abuse of these drugs. Two CNS depressants notorious for their roles in date rape are discussed in Box 40–1.

Drug abuse IV: major drugs of abuse other than alcohol and nicotine

Category

Examples

Opioids

Heroin

Morphine

Meperidine

Oxycodone

Hydromorphone

Psychostimulants

Cocaine

Dextroamphetamine

Methamphetamine

Methylphenidate

Depressants

Barbiturates

Amobarbital

Secobarbital

Pentobarbital

Phenobarbital

Benzodiazepines

Diazepam

Flunitrazepam

Lorazepam

Miscellaneous

Alcohol

Methaqualone

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate

Meprobamate

Psychedelics

LSD

Mescaline

Psilocybin

Dimethyltryptamine

Dissociative Drugs

Phencyclidine

Ketamine

Anabolic Steroids

Nandrolone

Oxandrolone

Testosterone

Miscellaneous

Dextromethorphan

Marijuana

Nicotine

Nitrous oxide

Amyl nitrite

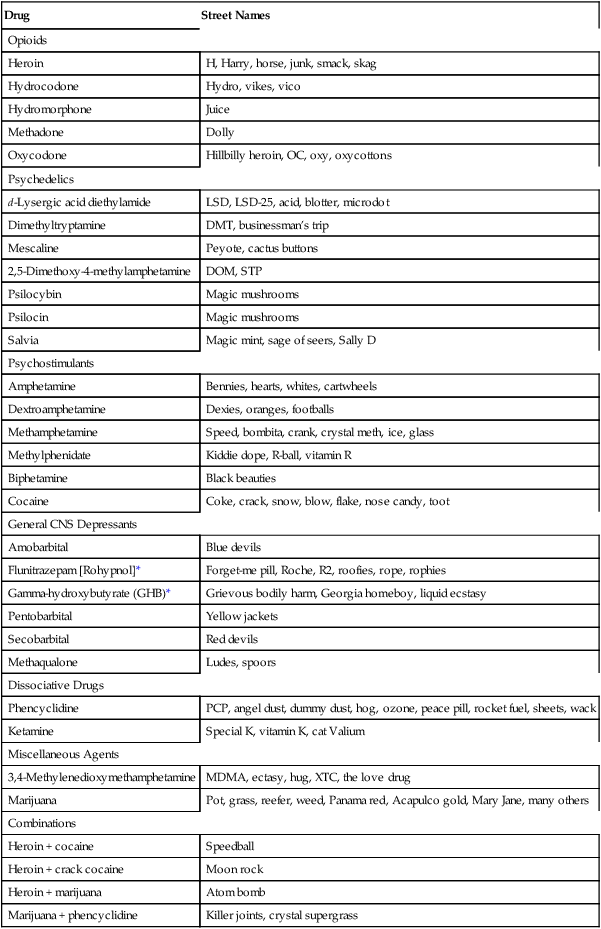

Drug

Street Names

Opioids

Heroin

H, Harry, horse, junk, smack, skag

Hydrocodone

Hydro, vikes, vico

Hydromorphone

Juice

Methadone

Dolly

Oxycodone

Hillbilly heroin, OC, oxy, oxycottons

Psychedelics

d-Lysergic acid diethylamide

LSD, LSD-25, acid, blotter, microdot

Dimethyltryptamine

DMT, businessman’s trip

Mescaline

Peyote, cactus buttons

2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine

DOM, STP

Psilocybin

Magic mushrooms

Psilocin

Magic mushrooms

Salvia

Magic mint, sage of seers, Sally D

Psychostimulants

Amphetamine

Bennies, hearts, whites, cartwheels

Dextroamphetamine

Dexies, oranges, footballs

Methamphetamine

Speed, bombita, crank, crystal meth, ice, glass

Methylphenidate

Kiddie dope, R-ball, vitamin R

Biphetamine

Black beauties

Cocaine

Coke, crack, snow, blow, flake, nose candy, toot

General CNS Depressants

Amobarbital

Blue devils

Flunitrazepam [Rohypnol]*

Forget-me pill, Roche, R2, roofies, rope, rophies

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)*

Grievous bodily harm, Georgia homeboy, liquid ecstasy

Pentobarbital

Yellow jackets

Secobarbital

Red devils

Methaqualone

Ludes, spoors

Dissociative Drugs

Phencyclidine

PCP, angel dust, dummy dust, hog, ozone, peace pill, rocket fuel, sheets, wack

Ketamine

Special K, vitamin K, cat Valium

Miscellaneous Agents

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

MDMA, ectasy, hug, XTC, the love drug

Marijuana

Pot, grass, reefer, weed, Panama red, Acapulco gold, Mary Jane, many others

Combinations

Heroin + cocaine

Speedball

Heroin + crack cocaine

Moon rock

Heroin + marijuana

Atom bomb

Marijuana + phencyclidine

Killer joints, crystal supergrass

Structural formulas of representative drugs of abuse.

Structural formulas of representative drugs of abuse.

(LSD = d-lysergic acid diethylamide; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol.)

Heroin, oxycodone, and other opioids

Preferred drugs and routes of administration

Oxycodone.

Tolerance and physical dependence

Treatment of acute toxicity

Drugs for long-term management of opioid addiction

Drug

Trade Name

Formulation

Dosing Schedule

CSA Schedule

Comments

Opioid Agonist

Methadone

Methadose, Diskets

Dispersible tablets used to make an oral suspension

Once a day

II

Methadone maintenance may be provided only by Opioid Treatment Programs certified by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and approved by the designated state authority.

Methadose

Concentrated oral liquid

Once a day

Opioid Agonist-Antagonist

Buprenorphine

Subutex

Sublingual tablet

Once a day

III

Subutex and Suboxone may be prescribed in a primary care setting by any physician or nurse practitioner who has received authorized training and has registered with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Suboxone*

Sublingual tablet

Once a day

Suboxone*

Sublingual film

Once a day

Probuphine†

Sustained-release subdermal implant

Lasts at least 6 months

Opioid Antagonist

Naltrexone

ReVia

Oral tablet

Once a day

NR

Naltrexone is not a controlled substance and hence prescribers do not require special training or certification. IM naltrexone [Vivitrol] is the only drug approved for opioid addictions that is given monthly, rather than daily. Before receiving naltrexone, patients must undergo opioid detoxification.

Vivitrol

Extended-release suspension for IM injection

Once a month

Buprenorphine.

General CNS depressants

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drug abuse IV: major drugs of abuse other than alcohol and nicotine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access