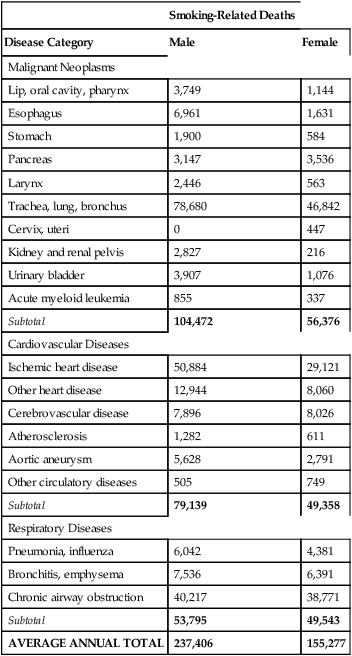

CHAPTER 39 Cigarette smoking remains the greatest single cause of preventable illness and premature death. In the United States, smoking kills more than 443,000 adults each year—about 1 of every 5 deaths. Around the world, tobacco kills over 5 million people each year. On average, male smokers die 13.2 years prematurely, and females die 14.5 years prematurely. As shown in Table 39–1, most deaths result from lung cancer (125,522), heart disease (101,009), and chronic airway obstruction (79,898). Not only do cigarettes kill people who smoke, every year, through secondhand smoke, cigarettes kill about 50,000 nonsmoking Americans, and about 600,000 nonsmokers worldwide. The direct medical costs of smoking exceed $95 billion a year. Indirect costs, including lost time from work and disability, add up to an additional $97 billion. In the United States, the prevalence of smoking among adults fell steadily from 1965 (42%) through the 1980s and 1990s, but has now leveled off, remaining constant between 2004 (20.9%) and 2008 (20.6%). TABLE 39–1 Average Annual Smoking-Attributable Mortality (United States, 2000–2004)* *Data are for adults ages 35 and older, and do not include deaths caused by burns or secondhand smoke. Data were obtained online at apps.nccd.cdc.gov/sammec/—the web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Smoking-Attributable Mortality, Morbidity, and Economic Costs (SAMMEC). • Strengthen advertising restrictions, including the prohibition on marketing to youth. • Require revised and more prominent warning labels. • Require disclosure of all ingredients in tobacco products and restrict harmful additives. • Monitor nicotine yields, and mandate gradual nicotine reduction to nonaddictive levels. Nicotine exposure during gestation can harm the fetus, and nicotine in breast milk can harm the nursing infant. Nonetheless, as discussed in Box 39–1, since pharmaceutical nicotine is safer than tobacco smoke, it is reasonable to consider using nicotine therapy during pregnancy to help a woman quit smoking. According to a 2004 report from the U.S. Surgeon General, the adverse consequences of smoking are more extensive than previously understood. It is now clear that chronic smoking can injure nearly every organ of the body. We already knew that smoking could cause cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, and cancers of the larynx, lung, esophagus, oral cavity, and bladder. New additions to the list include leukemia, cataracts, pneumonia, periodontal disease, type 2 diabetes, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and cancers of the cervix, kidney, pancreas, and stomach. Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of low birth weight, preterm labor, stillbirth, miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, perinatal mortality, and sudden infant death. As shown in Table 39–1, the leading causes of smoking-related death are lung cancer, ischemic heart disease, and chronic airway obstruction.

Drug abuse III: nicotine and smoking

Smoking-Related Deaths

Disease Category

Male

Female

Malignant Neoplasms

Lip, oral cavity, pharynx

3,749

1,144

Esophagus

6,961

1,631

Stomach

1,900

584

Pancreas

3,147

3,536

Larynx

2,446

563

Trachea, lung, bronchus

78,680

46,842

Cervix, uteri

0

447

Kidney and renal pelvis

2,827

216

Urinary bladder

3,907

1,076

Acute myeloid leukemia

855

337

Subtotal

104,472

56,376

Cardiovascular Diseases

Ischemic heart disease

50,884

29,121

Other heart disease

12,944

8,060

Cerebrovascular disease

7,896

8,026

Atherosclerosis

1,282

611

Aortic aneurysm

5,628

2,791

Other circulatory diseases

505

749

Subtotal

79,139

49,358

Respiratory Diseases

Pneumonia, influenza

6,042

4,381

Bronchitis, emphysema

7,536

6,391

Chronic airway obstruction

40,217

38,771

Subtotal

53,795

49,543

AVERAGE ANNUAL TOTAL

237,406

155,277

Basic pharmacology of nicotine

Pharmacologic effects

Effects during pregnancy and lactation.

Chronic toxicity from smoking

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Drug abuse III: nicotine and smoking

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access