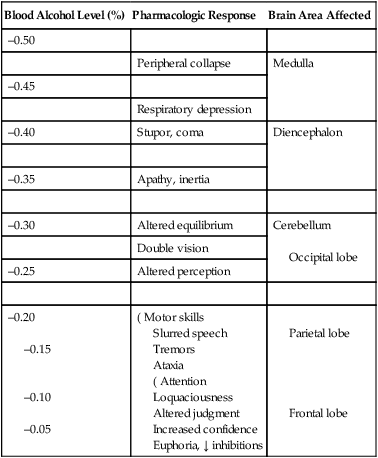

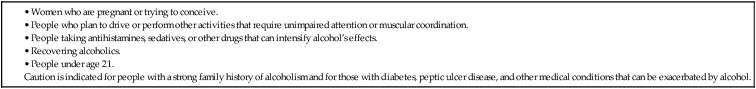

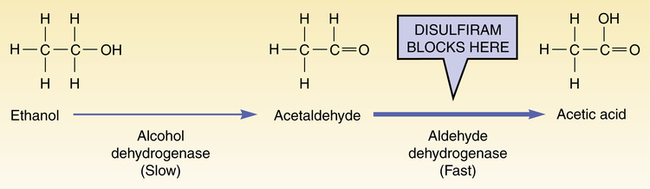

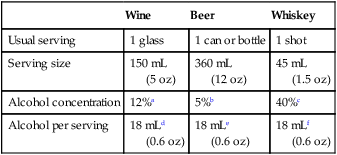

CHAPTER 38 The depressant effects of alcohol are dose dependent. When dosage is low, higher brain centers (cortical areas) are primarily affected. As dosage increases, more primitive brain areas (eg, medulla) become depressed. With depression of cortical function, thought processes and learned behaviors are altered, inhibitions are released, and self-restraint is replaced by increased sociability and expansiveness. Cortical depression also impairs motor function. As CNS depression deepens, reflexes diminish greatly and consciousness becomes impaired. At very high doses, alcohol produces a state of general anesthesia. (Alcohol can’t be used for anesthesia because the doses required are close to lethal.) Table 38–1 summarizes the effects of alcohol as a function of blood alcohol level and indicates the brain areas involved. TABLE 38–1 Central Nervous System Responses at Various Blood Alcohol Levels Not all of the cardiovascular effects of alcohol are deleterious: There is clear evidence that people who drink moderately (2 drinks a day or less for men, 1 drink a day or less for women) experience less ischemic stroke, coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction (MI), and heart failure than do abstainers. It is important to note, however, that heavy drinking (5 or more drinks/day) increases the risk of heart disease and stroke. How does moderate drinking protect against heart disease? Primarily by raising levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. As discussed in Chapter 50, HDL cholesterol protects against CAD, whereas low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol promotes CAD. Of all the agents that can raise HDL cholesterol, alcohol is the most effective known. In addition to raising HDL cholesterol, alcohol may confer protection through four other mechanisms: decreasing platelet aggregation, decreasing levels of fibrinogen (the precursor of fibrin, which reinforces clots), increasing levels of tissue plasminogen activator (a clot-dissolving enzyme), and suppressing the inflammatory component of atherosclerosis. The degree of cardiovascular protection is nearly equal for beer, wine, and distilled spirits. That is, protection is determined primarily by the amount of alcohol consumed—not by the particular beverage the alcohol is in. Also, the pattern of drinking matters: protection is greater for people who drink moderately 3 or 4 days a week than for people who drink just 1 or 2 days a week. Finally, cardioprotection is greatest for those with an unhealthy lifestyle: Among people who exercise, eat fruits and vegetables, and do not smoke, alcohol has little or no effect on the incidence of coronary events; conversely, among people who lack these health-promoting behaviors, moderate alcohol intake is associated with a 50% reduction in coronary risk. Interestingly, people who consume moderate amounts of alcohol live longer than those who abstain—and combining regular exercise with moderate drinking prolongs life even more. Compared with nondrinkers, moderate drinkers have a 30% lower mortality rate, a 50% lower incidence of MI, and a 59% lower incidence of heart failure. According to a study by the American Medical Association, if all Americans were to give up drinking, deaths from heart disease would increase by 81,000 a year. Hence, for people who already are moderate drinkers, continued moderate drinking would seem beneficial. Conversely, despite the apparent benefits of drinking—and the apparent health disadvantage of abstinence—no one is recommending that abstainers take up drinking. Furthermore, when the risks of alcohol outweigh any possible benefits—as in the examples listed in Table 38–2—then alcohol consumption should be avoided entirely. TABLE 38–2 People Who Should Avoid Alcohol* • Women who are pregnant or trying to conceive. • People who plan to drive or perform other activities that require unimpaired attention or muscular coordination. • People taking antihistamines, sedatives, or other drugs that can intensify alcohol’s effects. Caution is indicated for people with a strong family history of alcoholism and for those with diabetes, peptic ulcer disease, and other medical conditions that can be exacerbated by alcohol. *According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. How does alcohol prolong life? In large part by reducing cardiovascular disease. For people who drink red wine, a small benefit may come from resveratrol, although the amount present appears too small to have a significant effect (see Chapter 108). Alcohol is metabolized in both the liver and stomach. The liver is the primary site. The pathway for alcohol metabolism is shown in Figure 38–1. As depicted, the process begins with conversion of alcohol to acetaldehyde, a reaction catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase. This reaction is slow and puts a limit on the rate at which alcohol can be inactivated. Once formed, acetaldehyde undergoes rapid conversion to acetic acid. Through a series of reactions, acetic acid is then used to synthesize cholesterol, fatty acids, and other compounds. The information in Table 38–3 helps explain why we can’t metabolize more than 1 drink’s worth of alcohol per hour. As the table indicates, beer, wine, and whiskey differ from one another with respect to alcohol concentration and usual serving size. However, despite these differences, it turns out that the average can of beer, the average glass of wine, and the average shot of whiskey all contain the same amount of alcohol—namely, 18 mL (0.6 oz). Since the liver can metabolize about 15 mL of alcohol per hour, and since the average alcoholic drink contains 18 mL of alcohol, 1 drink contains just about the amount of alcohol that the liver can comfortably process each hour. Consumption of more than 1 drink per hour will overwhelm the capacity of the liver for alcohol metabolism, and therefore alcohol will accumulate. TABLE 38–3 Alcohol Content of Beer, Wine, and Whiskey aThe alcohol content of wine varies from 8% to 20%; typical table wines contain 12%. bThe alcohol content of beer varies: 5% alcohol is typical of American premium beers; cheaper American beers and light beers have less alcohol (2.4% to 5%); and imported beers may have more alcohol (6%). Beer sold in Europe may have 7% to 8% alcohol. cWhiskeys and other distilled spirits (eg, rum, vodka, gin) are usually 80 proof (40% alcohol) but may also be 100 proof (50% alcohol). dThe alcohol in a 5-ounce glass of wine varies from 12 to 30 mL, depending on the alcohol concentration in the wine. Wine with 12% alcohol has 18 mL of alcohol per 5-ounce glass. eThe alcohol in a 12-ounce can of beer varies from 9 to 29 mL, depending on the alcohol concentration in the beer. Beer with 5% alcohol has 18 mL per 12-ounce can. fThe alcohol in a 1.5-ounce shot of whiskey can be either 18 or 22.5 mL, depending on the proof of the whiskey. Eighty-proof whiskey has 18 mL of alcohol per 1.5-ounce serving.

Drug abuse II: alcohol

Basic pharmacology of alcohol

Central nervous system effects

Acute effects.

Blood Alcohol Level (%)

Pharmacologic Response

Brain Area Affected

–0.50

Peripheral collapse

Medulla

–0.45

Respiratory depression

–0.40

Stupor, coma

Diencephalon

–0.35

Apathy, inertia

–0.30

Altered equilibrium

Cerebellum

Occipital lobe

Double vision

–0.25

Altered perception

–0.20

–0.15

–0.10

–0.05

( Motor skills

Slurred speech

Tremors

Ataxia

( Attention

Loquaciousness

Altered judgment

Increased confidence

Euphoria, ↓ inhibitions

Parietal lobe

Frontal lobe

Other pharmacologic effects

Cardiovascular system.

Impact on longevity

Pharmacokinetics

Metabolism.

Ethanol metabolism and the effect of disulfiram.

Ethanol metabolism and the effect of disulfiram.

Conversion of ethanol into acetaldehyde takes place slowly (about 15 mL/hr). Consumption of more than 15 mL/hr will cause ethanol to accumulate. Effects of disulfiram result from accumulation of acetaldehyde secondary to inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Wine

Beer

Whiskey

Usual serving

1 glass

1 can or bottle

1 shot

Serving size

150 mL

(5 oz)

360 mL

(12 oz)

45 mL

(1.5 oz)

Alcohol concentration

12%a

5%b

40%c

Alcohol per serving

18 mLd

(0.6 oz)

18 mLe

(0.6 oz)

18 mLf

(0.6 oz)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree