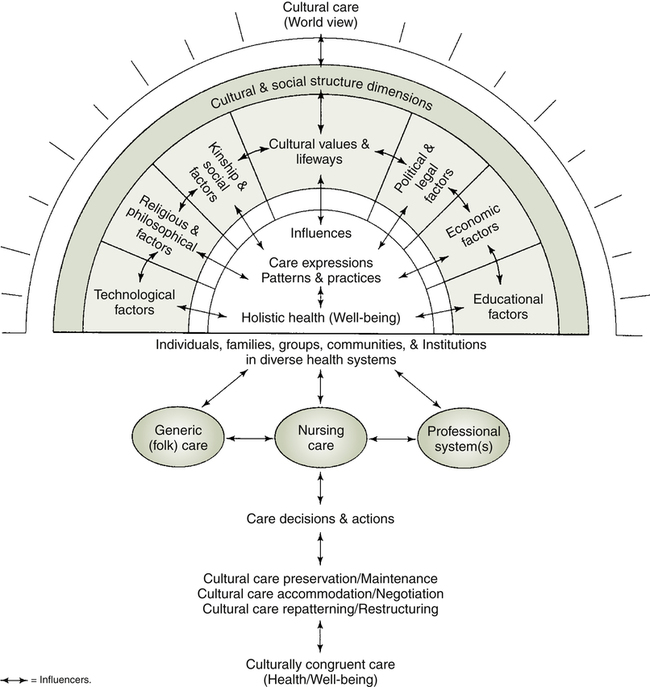

Cathy L. Campbell, PhD, APN-BC and Ishan C. Williams, PhD At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe nursing care strategies that may be used to provide care to a diverse patient population. • Describe methods used to become culturally competent. • Identify societal factors affecting the delivery of culturally responsive nursing care in the United States. • Identify barriers to and resources for minority access to care in the United States. • Describe the differences in the concepts of race, culture, and ethnicity. • Discuss strategies to approach diverse populations in the provision of culturally relevant care. We live in a pluralistic society, and it is becoming more evident that cultural differences, if not acknowledged, will increasingly serve to isolate and alienate us from one another. It is not enough to simply educate people about cultural differences; one must also confront these competing standards of truth. Given that health care professionals learn from their culture the “art” of being healthy or ill, it is imperative for health professionals to treat each patient with respect to his or her own cultural background. Culture can be defined in multiple ways. In general, most definitions encompass socially inherited and shared beliefs, practices, habits, customs, language, and rituals. Culture shapes how people view their world and how they function within that world. Culture can transcend generations. The one unifying theme in defining culture is that it is learned. Much of what we believe, think, and act is attributable to culture. Hence one’s culture can profoundly determine what is perceived as health versus illness. There are also numerous definitions for diversity. Many people define diversity simply as racial or ethnic differences. This chapter considers diversity more broadly to encompass differences that may be rooted not only in culture, but also in age, health status, gender, sexual orientation, racial or ethnic identity, geographical location, or other aspects of sociocultural description and socioeconomic position (Kennedy, Fisher, Fontaine, & Martin-Holland, 2008). Given the importance of culture in how we define ourselves and our environment, each person must be treated with respect and his or her cultural sensitivity must be valued. How nurses incorporate the patient’s cultural diversity in their general plans of care can mean the difference between success and failure (Seidel, Ball, Dains, & Benedict, 2006). Kleinman and Benson (2006) notes that cultural issues are crucial to all clinical care and management of illness, because culture shapes health-related beliefs, values, and behaviors. Thus providing culturally responsive care requires that the nurse, when confronted with culturally diverse patients, is attuned to the cultural cues presented while balancing sensitivity, knowledge, and skills to accommodate social, cultural, biological, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of the client respectfully. When clinicians are focused only on the disease without a context, there is a distortion of reality. The importance of being sensitive to cultural diversity cannot be overemphasized. The ability to build on the strengths of diverse communities and to understand and respect other cultures results in interventions that can lead to healthy practices and behaviors. Health and illness can be perceived in a variety of ways, and acknowledging the significance of culture in people’s problems as well as their solutions is essential. Moreover, numerous expectations exist of what is considered appropriate treatment and care. Cultural values and social norms are major influences and can greatly affect the interaction and outcomes for both nurses and patients (Box 14-1). As the United States continues to increase in diversity, nurses will be providing care for patients from many backgrounds different from their own. It would not be feasible or realistic for nurses to try to memorize cultural traits from every diverse cultural group (Engebretson, Mahoney, & Carlson, 2008). Instead, nurses must have an appreciation of the cultural differences among his or her clients, respect each client’s culture, and behave in a way that demonstrates this respect. Many theoretical frameworks exist to provide nurses with a contextual basis for understanding and providing culturally and linguistically appropriate care. Leininger’s (1991) theoretical framework for transcultural nursing emphasizes the commonalities and differences among world views that reflect various aspects of society to diverse health systems (Figure 14-1). This depiction of the many interrelated dimensions of culture and care is useful for exploring important meanings and patterns of care. The theoretical framework is focused on comparative culture care examined through a holistic and multidimensional lens (Leininger, 2002). The purpose of the theory is to provide culturally congruent, safe, and meaningful care to clients from different or similar cultures. Furthermore, the theory posits that world view, cultural, and social structures and others influence care outcomes related to culturally congruent care; generic emic (folk) practices (an attempt to understand the viewpoint of the people themselves) and professional ethic nursing practices (according to the principles, methods, and interests of the observer) influence outcomes; and the three modes for transcultural care actions and decisions are culture preservation and/or maintenance, cultural care accommodation and/or negotiation, and cultural care repatterning and/or restructuring to provide culturally congruent care (Leininger, 2002). When nurses work with patients who have cultural orientations that are different in minor or major ways from their own, those considerations are particularly significant. Further discussion of Leininger’s framework occurs in Chapter 5. Another model for examining cultural competence in nursing care is the Campinha-Bacote Model of Cultural Competence (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). In this model, nurses continuously work toward cultural competence by addressing five constructs: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, cultural encounters, and cultural desire. The final—and perhaps the most important—concept in the model is cultural desire: “Cultural desire is the spiritual and pivotal construct that provides the energy source and foundation for the health care provider’s journey toward cultural competence” (Campinha-Bacote, 2002). Thus cultural competence can be illustrated as a volcano, depicting how cultural desire stimulates the process of cultural competence. Similar to the Campinha-Bacote model, the U.S. Health Resources Services Administration attempted to identify the critical domains of cultural competence for health care providers and organizations (USDHHS, 2006). These nine domains are value and attitudes, cultural sensitivity, communication, policies and procedures, training and development, facility characteristics, intervention and treatment models, family and community participation, and monitoring and evaluation. By addressing all nine domains, both health care providers and organizations can achieve cultural competence. The discipline of nursing reflects the values and norms of a society; in the United States these values and norms are predominantly Eurocentric, middle class, Christian, and androcentric in view. In general, the American culture tends to value personal freedom and independence (Shaw & Degazon, 2008), as well as individual achievement over the common good (Seidel et al., 2006). For example, the concept of a single autonomous decision maker that is the hallmark of a Eurocentric world view does not accurately capture the involvement of family members and other significant people in health care decision making (Campbell, 2007). The notion that everyone be treated exactly the same is idealized and unrealistic. Traditionally, health care providers are presumed to know more about their patients’ needs than patients themselves do. This concept, known as paternalism, is discussed further in Chapter 12. Although there is a growing movement to listen to patients’ goals and beliefs and incorporate such goals and beliefs as resources in their care, this continues to be a challenge when patients’ beliefs differ greatly from those of the providers of health care.

Diversity in Health and Illness

![]() Diversity and Health

Diversity and Health

VALUES THAT SHAPE HEALTH CARE AND NURSING

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access