Disorders

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Description

• Severe form of alveolar or acute lung injury resulting in damage to alveolar capillary membrane.

• Pulmonary edema in the absence of cardiac failure.

• Hallmark sign: hypoxemia despite increased supplemental oxygen

• Also called adult respiratory distress syndrome; ARDS; and shock, stiff, wet, or Da Nang lung (see Understanding ARDS)

Causes

Acute miliary tuberculosis

Anaphylaxis

Aspiration of gastric contents

Coronary artery bypass grafting

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Drug overdose

Idiosyncratic drug reaction

Indirect or direct lung trauma (most common)

Massive blood transfusions

Near drowning

Oxygen toxicity

Pancreatitis

Pulmonary infection

Sepsis

Thoracic trauma

Toxic inhalation of noxious gases and vapors

Venous air embolism, fat embolism

Signs and symptoms

Stage I

Shortness of breath, especially on exertion

Normal to increased respiratory and pulse rates

Anxiety, restlessness

Stage II

Respiratory distress

Thick, frothy sputum; bloody, sticky secretions

Bibasilar crackles

Cool, clammy skin; tachycardia; elevated blood pressure

Stage III

• Respiratory rate more than 30 breaths/minute, productive cough, crackles, and rhonchi

• Tachycardia with arrhythmias, labile blood pressure, pale, cyanotic skin

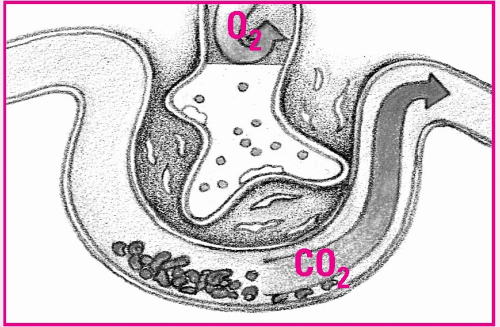

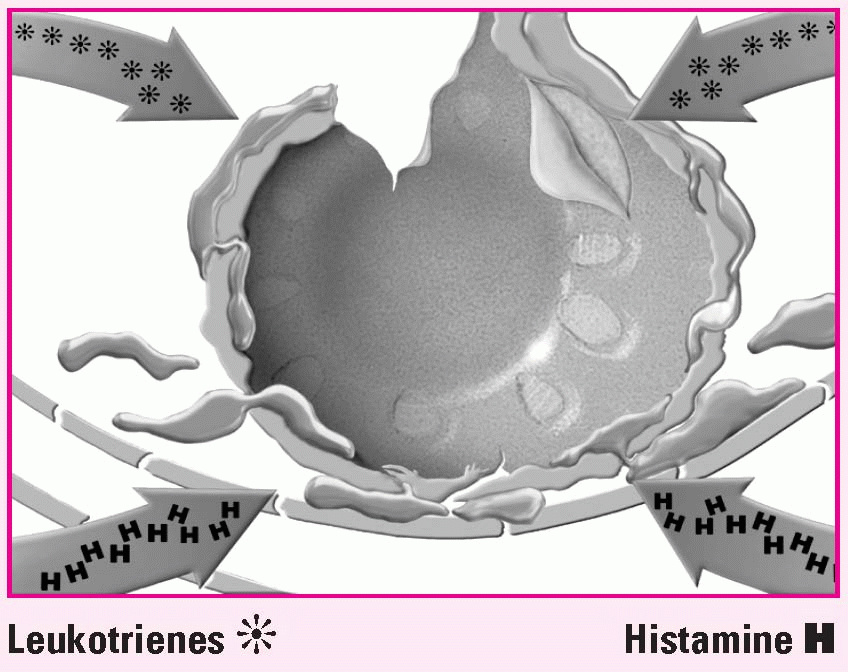

Understanding ARDS

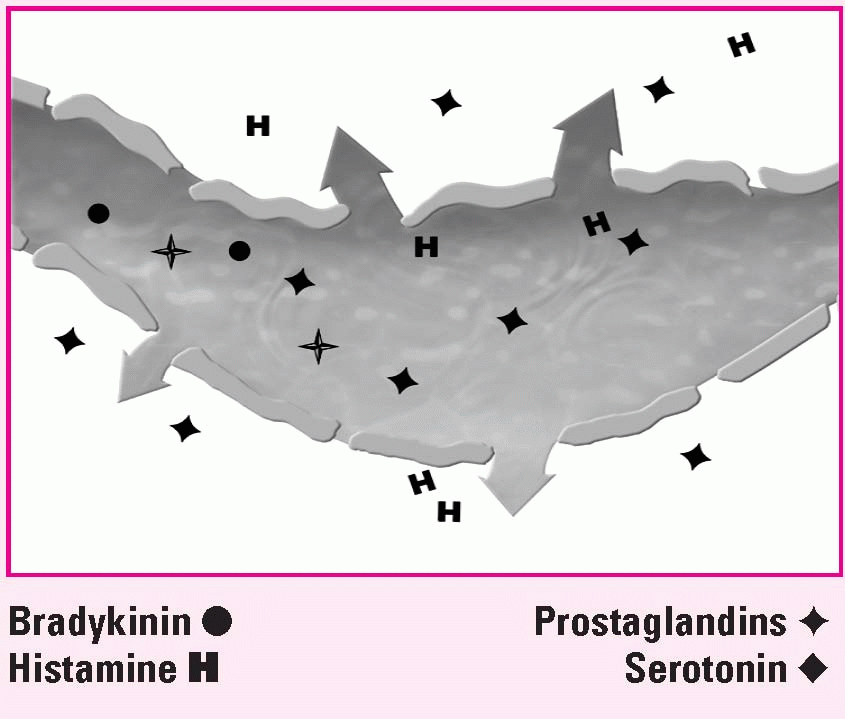

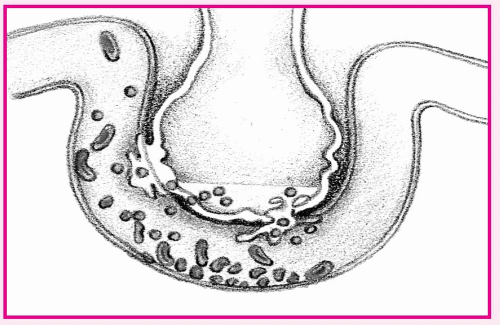

Phase 1. Injury reduces normal blood flow to the lungs. Platelets aggregate and release neutrophils (N), histamine (H), serotonin (S), and bradykinin (B). |

Phase 2. The released substances inflame and damage the alveolar capillary membrane, increasing capillary permeability. Fluids then shift into the interstitial space. |

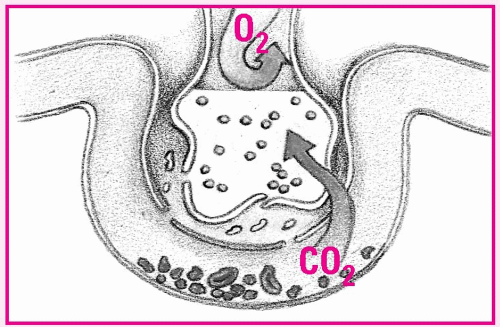

Phase 3. Capillary permeability increases and proteins and fluids leak out, increasing interstitial osmotic pressure and causing pulmonary edema. |

Phase 5. Oxygenation is impaired, but carbon dioxide (CO2) easily crosses the alveolar capillary membrane and is expired. Blood oxygen (O2) and CO2 levels are low. |

• Mental status changes

Stage IV

Acute respiratory failure with severe hypoxia

Metabolic and respiratory acidosis

Deteriorating mental status

Pale, cyanotic skin

Cardiac arrhythmias; hypotension

Potential multi-organ failure

Management

• Oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)

PEEP may lower cardiac output, so monitor for hypotension, tachycardia, and decreased urine output. To maintain PEEP, suction only as needed.

• Treatment of underlying cause

• Correction of electrolyte and acid-base imbalances

• Fluid restriction

• Tube feedings or parenteral nutrition

• Medications: antimicrobials, bronchodilators, mucolytics, corticosteroids, diuretics, fluids, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, sedatives, and vasopressors

• Frequent repositioning

• Frequent mouth care

Acute respiratory failure

Description

• Inadequate gas exchange and ventilation resulting from the inability of the lungs to adequately maintain arterial oxygenation or eliminate carbon dioxide

Causes

Airway irritants

Bronchospasm

Central nervous system depression

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation

Endocrine or metabolic disorders

Excessive secretions

Fluid overload

Gas exchange failure

Heart failure

Myocardial infarction

Pulmonary emboli

Respiratory tract infection

Thoracic abnormalities

Ventilatory failure

Signs and symptoms

Cyanosis of the oral mucosa, lips, and nail beds

Ashen skin; cold, clammy skin

Use of accessory muscles; pursed-lip breathing

Nasal flaring; rapid breathing

Asymmetrical chest movement

Anxiety, restlessness

Hyperresonance

Diminished or absent breath sounds

Wheezes (with asthma)

Rhonchi (with bronchitis)

Crackles (with pulmonary edema)

Management

• Oxygen therapy with mechanical ventilation

• Fluid restriction (with heart failure)

• Medications: antacids, antibiotics, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, diuretics, histamine-receptor antagonists, positive inotropic drugs, vasopressors

• Frequent repositioning

• Frequent mouth care

Anaphylaxis

Description

• Dramatic, acute atopic reaction to an allergen marked by sudden onset of rapidly progressive urticaria and respiratory distress

• Earlier signs and symptoms more severe after exposure to the antigen

• Severe reactions possibly initiating vascular collapse, leading to systemic shock and, possibly, death (see Understanding anaphylaxis, pages 58 and 59)

Causes

Systemic exposure to:

– blood transfusions

– contrast media

– foods (especially shellfish)

– insect venom

– latex

– other specific antigens

– sensitizing drugs

Signs and symptoms

• Anxiety

• Hives

• Angioedema

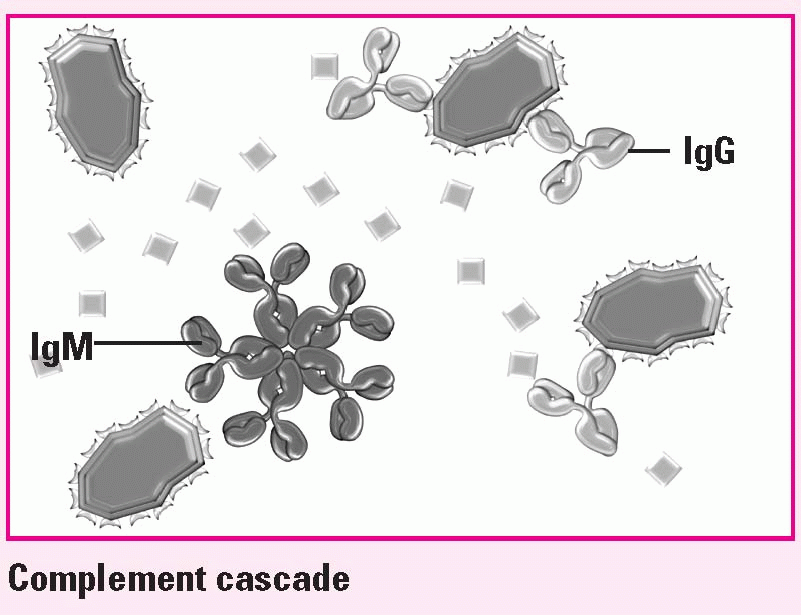

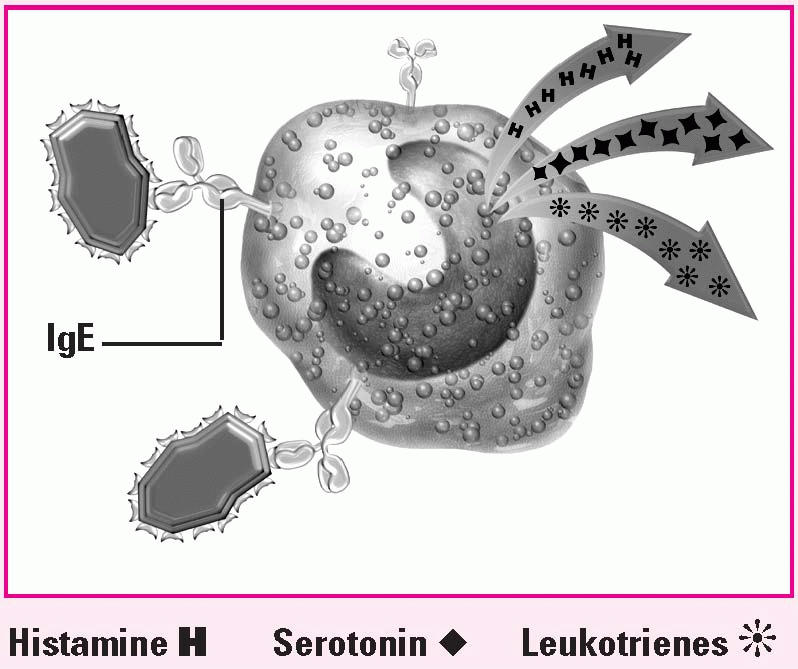

Understanding anaphylaxis

2. Release of chemical mediators

Activated IgE on basophils promotes release of mediators: histamine, serotonin, and leukotrienes.

|

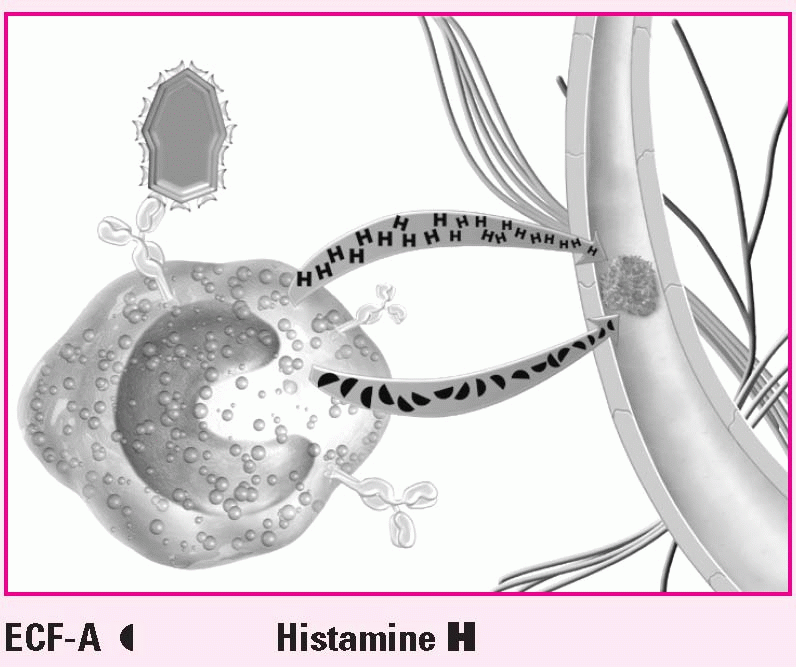

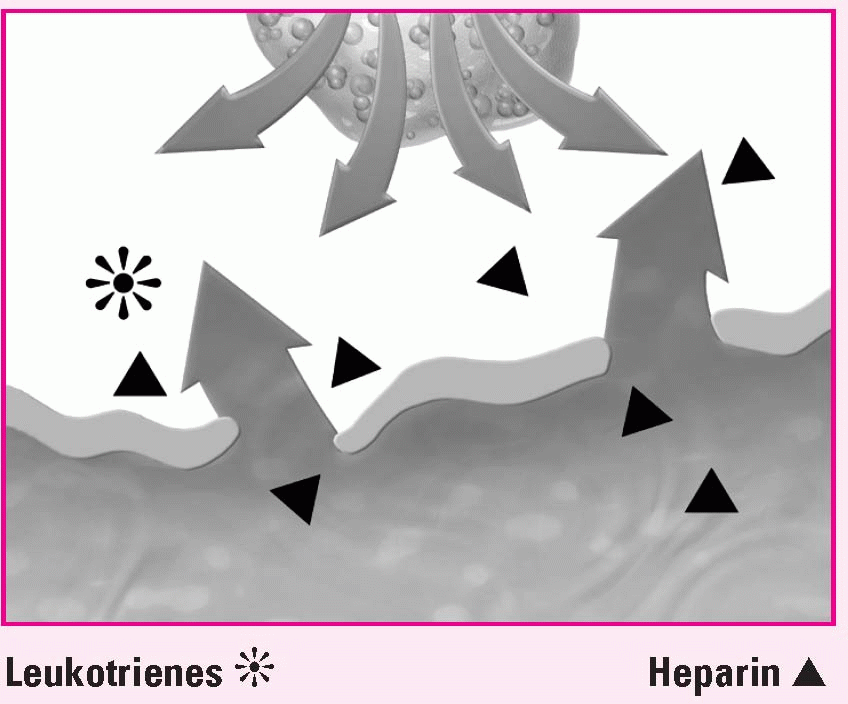

3. Intensified response

Mast cells release more histamine and eosinophil chemotactic factor of anaphylaxis (ECF-A), which create venuleweakening lesions.

|

4. Respiratory distress

In the lungs, histamine causes endothelial cell destruction and fluid leakage into alveoli.

|

5. Deterioration

Meanwhile, mediators increase vascular permeability, causing fluid to leak from the vessels.

|

• Hoarseness or stridor; wheezing

• Severe abdominal cramps, nausea, diarrhea

• Urinary urgency and incontinence

• Altered mental status, dizziness, drowsiness, headache, restlessness, seizures, and unresponsiveness

• Hypotension, shock; sometimes angina and cardiac arrhythmias

Management

• Removal of offending antigen

• Patent airway (establish and maintain); endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, if indicated

• Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, if cardiac arrest occurs

• Medications: immediate injection of epinephrine 1:1,000 aqueous solution subcutaneously or I.V; corticosteroids; antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl); bronchodilators; volume expander infusions as needed; vasopressors, such as norepinephrine (Levophed), and dopamine (Intropin).

Aneurysm, abdominal aortic

Description

• Abnormal dilation from a weakness in the arterial wall of the aorta, commonly between the renal arteries and iliac branches

• Can be fusiform (spindle-shaped), saccular (pouch like), or dissecting

Causes

Arteriosclerosis or atherosclerosis (95%)

Connective tissue disorders

Hypertension

Syphilis; other infections

Trauma

Signs and symptoms

Intact aneurysm

• Gnawing, generalized, steady abdominal pain; lower back pain unaffected by movement; sudden onset of severe abdominal pain or lumbar pain with radiation to flank and groin

• Gastric or abdominal fullness

• Possible pulsating mass in the periumbilical area

Ruptured aneurysm

• Into the peritoneal cavity: severe, persistent abdominal and back pain; into the duodenum: GI bleeding with massive hematemesis and melena

• Mottled to cyanotic skin, poor distal perfusion, absent peripheral distal pulses

• Decreased level of consciousness, syncope, diaphoresis, hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria

• Distended abdomen, ecchymosis or hematoma in the abdominal, flank, or groin area

• Systolic bruit over the aorta

Management

• Control of hypertension; fluid and blood replacement with rupture

• Medications: analgesics, antibiotics, antihypertensives, beta-adrenergic blockers

• Endovascular grafting or surgical resection for those that produce symptoms; bypass procedures for poor perfusion distal to aneurysm; graft replacement for repair of ruptured aneurysm

If rupture does occur, surgery must be done immediately. A pneumatic antishock garment may be used while transporting the patient to surgery.

After surgery

Pulse assessment

Blood pressure maintenance

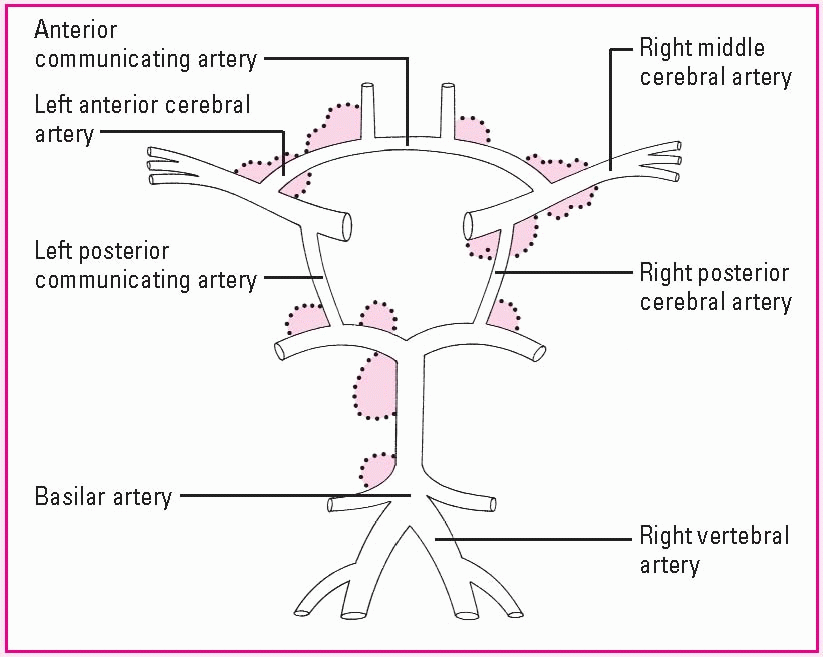

Aneurysm, cerebral

Description

• Weakness in the wall of a cerebral artery causing localized dilation

• Berry aneurysm (most common form); saclike outpouching in a cerebral artery

• Usually occurs at an arterial junction in the Circle of Willis, the circular anastomosis forming the major cerebral arteries at the base of the brain

• Commonly ruptures, causing subarachnoid hemorrhage

Causes

• Congenital defect, degenerative process, or combination (see How a cerebral aneurysm develops, page 62)

• Trauma

Signs and symptoms

• Based on the site and amount of bleeding

• Vision defects

• Grade I (minimal bleeding): no neurologic deficit; possibly having slight headache and nuchal rigidity

How a cerebral aneurysm develops

In an intracranial (cerebral) aneurysm, weakness in the wall of a cerebral artery causes localized dilation. Blood flow exerts pressure against the wall, stretching it like a balloon and making it likely to rupture. Cerebral aneurysms usually arise at the arterial bifurcation in the Circle of Willis and its branches. This illustration shows the most common sites around this circle.

|

• Grade II (mild bleeding): alert with a mild to severe headache and nuchal rigidity; possibly having third-nerve palsy

• Grade III (moderate bleeding): altered mental status, with nuchal rigidity and, possibly, a mild focal deficit

• Grade IV (severe bleeding): stuporous with nuchal rigidity and possibly mild to severe hemiparesis

• Grade V (moribund; commonly fatal): deep coma or decerebrate

Management

• Aneurysm precautions (bed rest in a quiet, darkened room, keeping the head of the bed flat or less than 30 degrees, as ordered; limited visitation; avoidance of strenuous physical activity and straining with bowel movements; and restricted fluid intake)

• Avoidance of coffee, other stimulants, and aspirin

• Medications: aminocaproic acid, analgesics, anticonvulsants, antihypertensives, calcium channel blockers, corticosteroids, sedatives

• Surgical repair by clipping, ligation, or wrapping (before or after rupture)

Arterial occlusive disease

Description

• An obstruction or narrowing of the lumen of the aorta and its major branches; may affect the carotid, vertebral, innominate, subclavian, femoral, iliac, renal, mesenteric, and celiac arteries

• Prognosis dependent on location of the occlusion and development of collateral circulation that counteracts reduced blood flow

Causes

Atheromatous debris (plaques)

Atherosclerosis

Direct blunt or penetrating trauma

Embolism

Fibromuscular disease

Immune arteritis

Indwelling arterial catheter

Raynaud’s disease

Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thrombosis

Signs and symptoms

• Narrowing of lumen may be present; may not cause symptoms

• Trophic changes and diminished or absent pulses of involved arm or leg, pallor with elevation of arm or leg, dependent rubor, ischemic ulcers

• Arterial bruit, hypertension

• Pain, pallor, pulselessness distal to the occlusion, paralysis and paresthesia occurring in the affected arm or leg, poikilothermy

• Sensory or motor deficits, expressive or receptive aphasia, vision disturbances

Management

• General: smoking cessation; hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia control; foot and leg care; weight control; low-fat, low-cholesterol, high-fiber diet; regular walking program

• Medications: anticoagulants, antihypertensives, antiplatelets, hypoglycemics, lipid-lowering drugs, niacin or vitamin B complex, thrombolytics

• Surgery: embolectomy, endarterectomy, atherectomy, laser surgery or angioplasty, endovascular stent placement, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, patch or bypass grafting, lumbar sympathectomy, amputation, bowel resection

• For chronic arterial occlusive disease use preventive measures, such as minimal pressure mattresses, heel protectors, a foot cradle, or a footboard.

• Preoperative care during an acute episode: circulatory status and pulse monitoring

• Frequent repositioning

• Avoid elevating or applying heat to the affected leg.

After surgery

• Pulse and circulation assessment

• With mesenteric artery occlusion: nasogastric decompression

• Maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance

Cardiac arrhythmias

Description

• Variations in the normal pattern of electrical conduction of the heart

• Vary in severity, from mild, producing no symptoms and requiring no treatment to catastrophic, requiring immediate resuscitation (see Comparing normal and abnormal conduction, pages 66 and 67)

• Classified according to their origin (atrial, junctional, ventricular or supraventricular); clinical significance determined by effect on cardiac output and blood pressure, partially affected by site of origin

Causes

Acid-base imbalances

Cellular hypoxia

Congenital defects

Connective tissue disorders

Degeneration of the conductive tissue

Drug toxicity

Electrolyte imbalances

Emotional stress

Hyperthyroidism

Hypertrophy of the heart muscle

Idiopathic or a combination of causes

Myocardial infarction or ischemia

Organic heart disease

Valvular heart disease

Signs and symptoms

• Circulatory failure along with an absence of pulse and respirations with asystole, ventricular fibrillation and, occasionally, with ventricular tachycardia; reduced urine output

• Pallor, cold and clammy extremities, hypotension

• Dyspnea

• Weakness, chest pain, dizziness, syncope (with severely impaired cerebral circulation)

• Palpitations

Management

• Supportive measures: cardiopulmonary resuscitation, defibrillation, adherence to ACLS protocols

• Medications: antiarrhythmics, electrolyte replacements

• Cardioversion

• Temporary or permanent placement of a pacemaker

• Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (if indicated)

• Ablation therapy for atrial arrhythmias

• Surgical removal or cryotherapy of an irritable ectopic focus to prevent recurring arrhythmias

• Treatment of the underlying disorder

• ECG monitoring

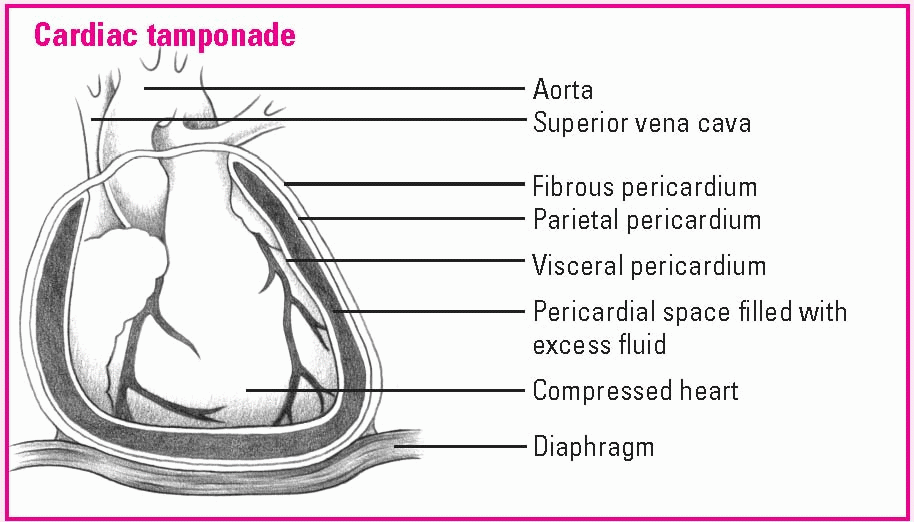

Cardiac tamponade

Description

• Rapid increase in intrapericardial pressure caused by fluid accumulation in the pericardial sac

• Impaired diastolic filling of the heart (see Understanding cardiac tamponade, page 68)

Causes

Acute myocardial infarction

Acute pericarditis

Acute rheumatic fever (rare)

Bacterial infections

Cardiac catheterization

Cardiac surgery

Chronic renal failure (rare)

Connective tissue disorders (rare)

Drug reaction

Effusion in cancer

Hemorrhage (nontraumatic cause)

Idiopathic

Radiation therapy

Trauma

Thrombolytic therapy

Tuberculosis

Viral pericarditis

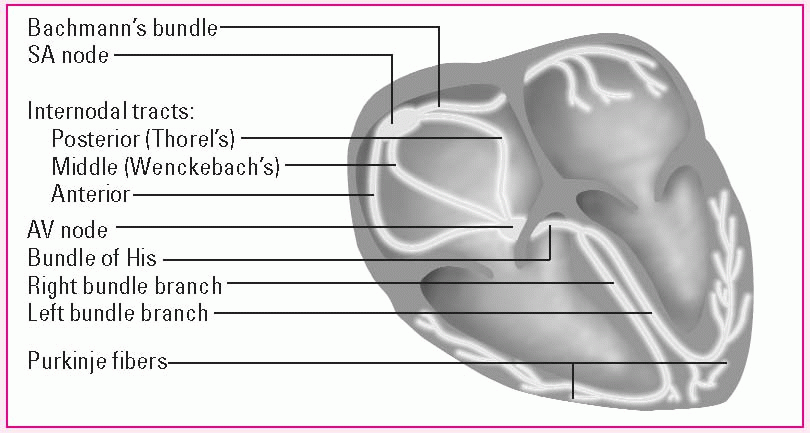

Comparing normal and abnormal conduction

Normal cardiac conduction

The conduction system of the heart, shown below, begins at the heart’s pacemaker, the sinoatrial (SA) node. When an impulse leaves the SA node, it travels through the atria along Bachmann’s bundle and the internodal pathways to the atrioventricular (AV) node and then down the bundle of His, along the bundle branches and, finally, down the Purkinje fibers to the ventricles.

|

Abnormal cardiac conduction

Altered automaticity, irritability, reentry, or conduction disturbances may cause cardiac arrhythmias.

Altered automaticity

Altered automaticity is the result of partial depolarization, which may increase the intrinsic rate of the SA node or latent pacemakers, or may induce ectopic pacemakers to reach threshold and depolarize.

Signs and symptoms

• Anxiety and restlessness, diaphoresis, pallor, or cyanosis

• Beck’s triad (jugular vein distention, hypotension, muffled heart sounds); edema; rapid, weak pulses; increased central venous pressure; pulsus paradoxus; narrow pulse pressure

Automaticity may be altered by such drugs as epinephrine, atropine, and digoxin (Lanoxin), and by such conditions as acidosis, alkalosis, hypoxia, myocardial infarction (MI), hypokalemia, hypermagnesemia, and hypocalcemia. Examples of arrhythmias caused by altered automaticity include atrial fibrillation and flutter, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, accelerated idioventricular and junctional rhythms, and premature atrial, junctional, and ventricular complexes.

Reentry

Reentry occurs when ischemia or deformation causes an abnormal circuit to develop within conductive fibers. Although current flow is blocked in one direction within the circuit, the descending impulse can travel in the other direction. By the time the impulse completes the circuit, the previously depolarized tissue within the circuit is no longer refractory to stimulation.

Conditions that increase the likelihood of reentry include hyperkalemia, myocardial ischemia, and the use of certain antiarrhythmic drugs. Reentry may be responsible for such arrhythmias as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and premature atrial, junctional, and ventricular complexes.

An alternative reentry mechanism depends on the presence of a congenital accessory pathway linking the atria and the ventricles outside the AV junction; for example, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Conduction disturbances

Conduction disturbances occur when impulses are conducted too quickly or too slowly. Possible causes include trauma, drug toxicity, myocardial ischemia, MI, and electrolyte abnormalities. The AV blocks occur as a result of conduction disturbances.

• Chest pain

• Hepatomegaly

Management

• Pericardiocentesis, if necessary

• Medications: inotropic drugs, intravascular volume expansion, oxygen

• Surgery: pericardiocentesis, pericardial window, subxiphoid pericardiotomy, complete pericardectomy, thoracotomy

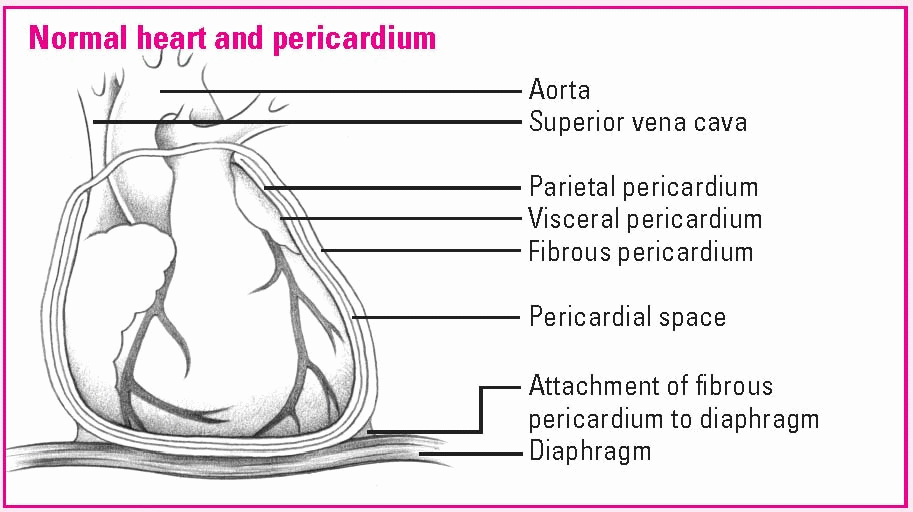

Understanding cardiac tamponade

The pericardial sac, which surrounds and protects the heart, is composed of several layers. The fibrous pericardium is the tough outermost membrane; the inner membrane, called the serous membrane, consists of the visceral and parietal layers. The visceral layer clings to the heart and is also known as the epicardial layer of the heart. The parietal layer lies between the visceral layer and the fibrous pericardium. The pericardial space—between the visceral and parietal layers—contains 10 to 30 ml of pericardial fluid. This fluid lubricates the layers and minimizes friction when the heart contracts.

|

In cardiac tamponade, blood or fluid fills the pericardial space, compressing the heart chambers, increasing intracardiac pressure, and obstructing venous return. As blood flow into the ventricles falls, so does cardiac output. Without prompt treatment, low cardiac output can be fatal.

|

Cerebral contusion

Description

• Ecchymosis of brain tissue resulting from injury to the head

Causes

• Acceleration-deceleration or coup-contrecoup injuries

• Head trauma

Complications may include intracranial hemorrhage, hematoma, tentorial herniation, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Signs and symptoms

• Unconscious patient: pale and motionless; altered vital signs

• Conscious patient: drowsy or easily disturbed

• Scalp wound

• Possible involuntary evacuation of bowel and bladder; hemiparesis

Management

• Establishment of a patent airway and adequate oxygenation and circulation

• Administration of I.V. fluids

Dextrose 5% in water should be avoided because it may increase cerebral edema.

• Minimization of environmental stimuli

• Nothing by mouth until fully conscious

• Medications: nonopioid analgesics

• Surgery: craniotomy, depending on severity or location

• Neurologic status monitoring

• Seizure precautions, if indicated

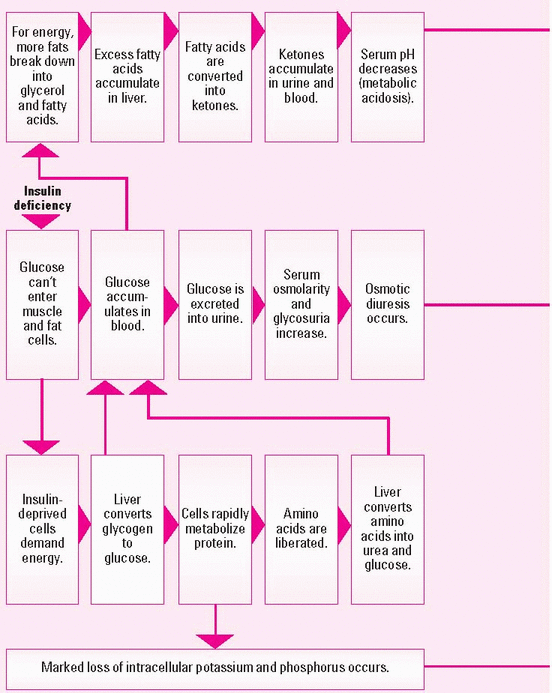

Diabetic ketoacidosis

Description

• Acute complication of hyperglycemic crisis possibly occurring in the patient with diabetes

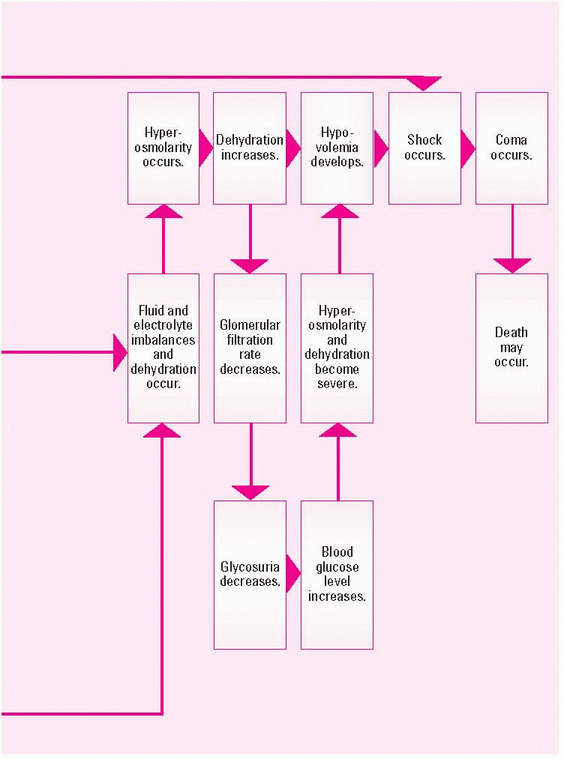

• If not treated properly, may result in coma or death (see What happens in diabetic ketoacidosis, pages 70 and 71)

• Also called DKA

Causes

• Autoimmune dysfunction

• Failure to take insulin or pump failure for those with insulin pumps

• Illness

• Other endocrine disease

• Recent stress or trauma

• Severe viral infection

• Use of drugs that increase blood glucose levels

Signs and symptoms

• Rapid onset of drowsiness, stupor, and coma

• Polyuria and extreme volume depletion resulting in hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, poor skin turgor, dry mucous membranes, decreased peripheral pulses, cool skin temperature, and decreased reflexes

• Hyperventilation

• Acetone breath odor

• Dry, flushed skin

• Polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia

Management

• Treatment of underlying cause

• Airway support and mechanical ventilation (for comatose patient)

• Insulin therapy, I.V. and fluid and electrolyte replacements (based on laboratory test results)

Patients with DKA are at high risk for hyperkalemia before treatment due to the movement of potassium out of the cells. After treatment is initiated and potassium begins to move back into the cells, be alert for hypokalemia.

• Fluid resuscitation

• Dietary management, as appropriate

• Medications: oral antidiabetics if stable conversion from insulin

• Blood glucose monitoring

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

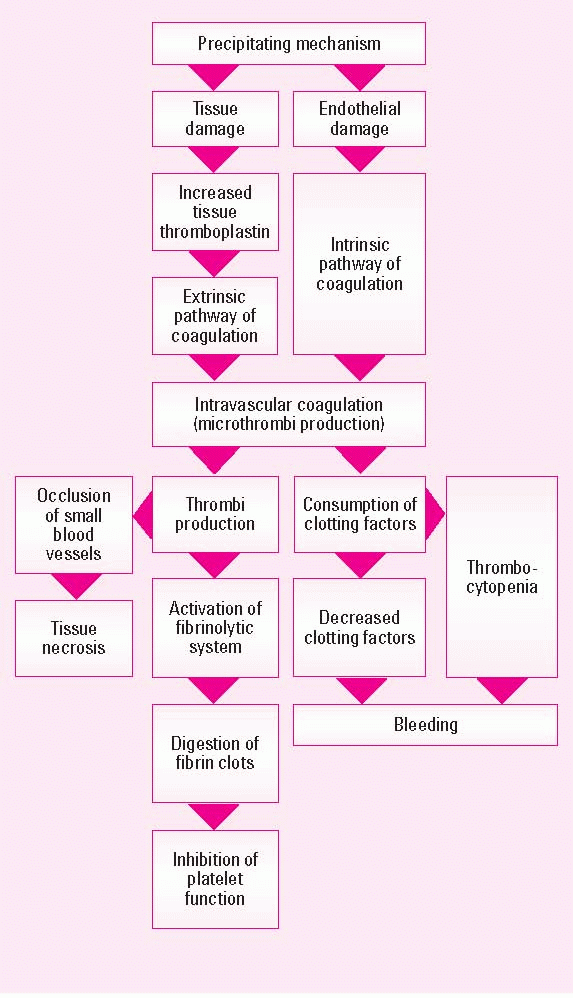

Description

• Syndrome of activated coagulation characterized by bleeding, thrombosis, or both

• Complicates diseases and conditions that accelerate clotting, causing occlusion of small blood vessels, organ necrosis, depletion of circulating clotting factors and platelets, and activation of the fibrinolytic system (see How disseminated intravascular coagulation happens)

• Also called DIC, consumption coagulopathy, and defibrination syndrome

Causes

• Acute respiratory distress syndrome

• Cardiac arrest

• Diabetic ketoacidosis

• Disorders that produce necrosis, such as extensive burns and trauma

• Drug reactions

• Heatstroke

• Incompatible blood transfusion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree