Height and weight conversions

Height conversion |

Weight conversion |

To convert a patient’s height from inches to centimeters, multiply the number of inches by 2.54. To convert a patient’s height from centimeters to inches, multiply the number of centimeters by 0.394. |

To convert a patient’s weight from pounds to kilograms, divide the number of pounds by 2.2 kg; to convert a patient’s weight from kilograms to pounds, multiply the number of kilograms by 2.2 lb. |

Imperial |

Inches |

Metric (cm) |

Pounds |

Kilograms |

4′ 8″ |

56 |

142.2 |

10 |

4.5 |

4′ 9″ |

57 |

144.8 |

20 |

9.1 |

4′ 10″ |

58 |

147.3 |

30 |

13.6 |

4′ 11″ |

59 |

149.9 |

40 |

18.2 |

5′ |

60 |

152.4 |

50 |

22.7 |

5′ 1″ |

61 |

154.9 |

60 |

27.3 |

5′ 2″ |

62 |

157.5 |

70 |

31.8 |

5′ 3″ |

63 |

160 |

80 |

36.4 |

5′ 4″ |

64 |

162.6 |

90 |

40.9 |

5′ 5″ |

65 |

165.1 |

100 |

45.5 |

5′ 6″ |

66 |

167.6 |

110 |

50 |

5′ 7″ |

67 |

170.2 |

120 |

54.5 |

5′ 8″ |

68 |

172.7 |

130 |

59.1 |

5′ 9″ |

69 |

175.3 |

140 |

63.6 |

5′ 10″ |

70 |

177.8 |

150 |

68.2 |

5′ 11″ |

71 |

180.3 |

160 |

72.7 |

6′ |

72 |

182.9 |

170 |

77.3 |

6′ 1″ |

73 |

185.4 |

180 |

81.8 |

6′ 2″ |

74 |

188 |

190 |

86.4 |

6′ 3″ |

75 |

190.5 |

200 |

90.9 |

|

|

|

210 |

95.5 |

|

|

|

220 |

100 |

|

|

|

230 |

104.5 |

|

|

|

240 |

109.1 |

|

|

|

250 |

113.6 |

|

|

|

260 |

118.2 |

Temperature conversion

To convert Fahrenheit to Celsius, subtract 32 from the temperature in Fahrenheit and then divide by 1.8; to convert Celsius to Fahrenheit, multiply the temperature in Celsius by 1.8 and then add 32.

(F − 32) ÷ 1.8 = degrees Celsius

(C × 1.8) + 32 = degrees Fahrenheit

Degrees Fahrenheit (°F) |

Degrees Celsius (°C) |

|---|

89.6 |

32 |

91.4 |

33 |

93.2 |

34 |

94.3 |

34.6 |

95.0 |

35 |

95.4 |

35.2 |

96.2 |

35.7 |

96.8 |

36 |

97.2 |

36.2 |

97.6 |

36.4 |

98 |

36.7 |

98.6 |

37 |

99 |

37.2 |

99.3 |

37.4 |

99.7 |

37.6 |

100 |

37.8 |

100.4 |

38 |

100.8 |

38.2 |

101 |

38.3 |

101.2 |

38.4 |

101.4 |

38.6 |

101.8 |

38.8 |

102 |

38.9 |

102.2 |

39 |

102.6 |

39.2 |

102.8 |

39.3 |

103 |

39.4 |

103.2 |

39.6 |

103.4 |

39.7 |

103.6 |

39.8 |

104 |

40 |

104.4 |

40.2 |

104.6 |

40.3 |

104.8 |

40.4 |

105 |

40.6 |

Performing auscultation

Auscultation of body sounds—particularly those produced by the heart, lungs, blood vessels, stomach, and intestines—detects both high-pitched and low-pitched sounds. You can perform auscultation directly over a body area using only your ears, but you’ll typically perform it indirectly, using a stethoscope.

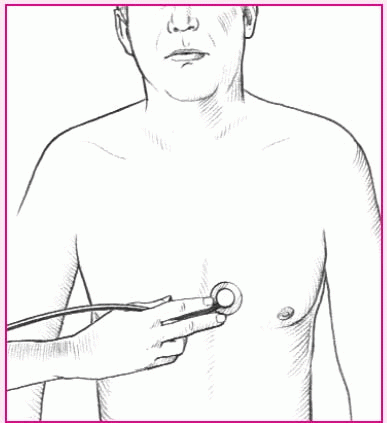

Assessing high-pitched sounds

To properly assess high-pitched sounds, such as breath sounds and first and second heart sounds, use the diaphragm of the stethoscope. Make sure you place the entire surface of the diaphragm firmly on the patient’s skin. If the area is excessively hairy, you can improve diaphragm contact and reduce background noise by applying water or water-soluble jelly to the skin before auscultating.

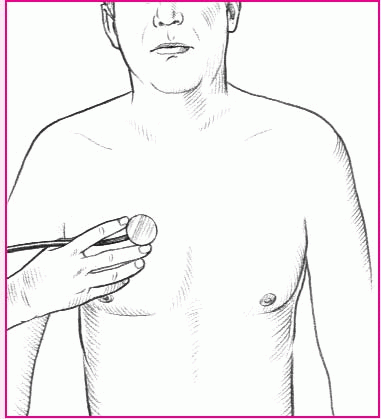

Assessing low-pitched sounds

To assess low-pitched sounds, such as heart murmurs and third and fourth heart sounds, lightly place the bell of the stethoscope on the appropriate area. Don’t exert pressure. If you do, the patient’s chest will act as a diaphragm and you will miss low-pitched sounds. If the patient is extremely thin or emaciated, use a stethoscope with a pediatric chest piece.

Performing percussion

Percussion has two basic purposes: to produce percussion sounds and to elicit tenderness. It involves three types: indirect, direct, and blunt.

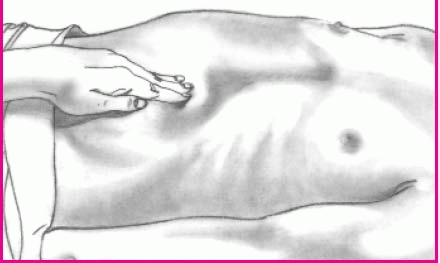

Indirect percussion

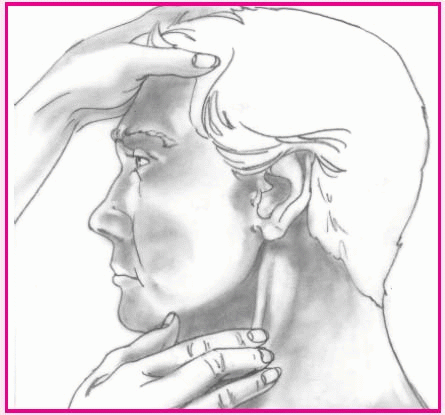

The most common method, indirect percussion, produces clear, crisp sounds when performed correctly. To perform indirect percussion, use the second finger of your nondominant hand as the pleximeter (the mediating device used to receive the taps) and the middle finger of your dominant hand as the plexor (the device used to tap the pleximeter). Place the pleximeter finger firmly against a body surface, such as the upper back or abdomen. With your wrist flexed loosely, use the tip of your plexor finger to deliver a crisp blow just beneath the distal joint of the pleximeter (as shown below). Make sure you hold the plexor perpendicular to the pleximeter. Tap lightly and quickly, removing the plexor as soon as you have delivered each blow.

Direct percussion

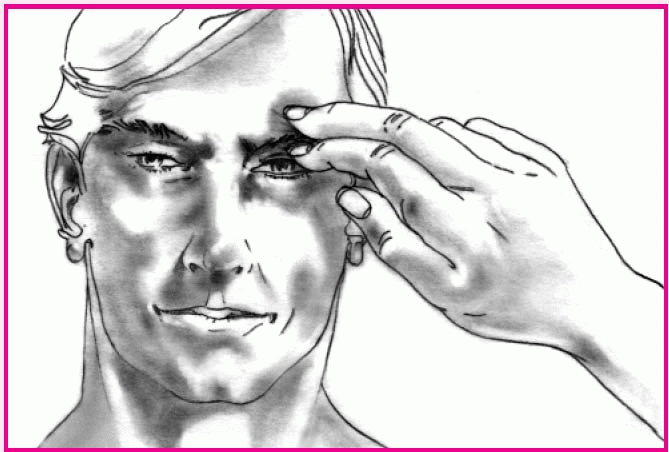

To perform direct percussion, tap your hand or fingertip directly against the body surface (as shown below). This method helps assess an adult’s sinuses for tenderness.

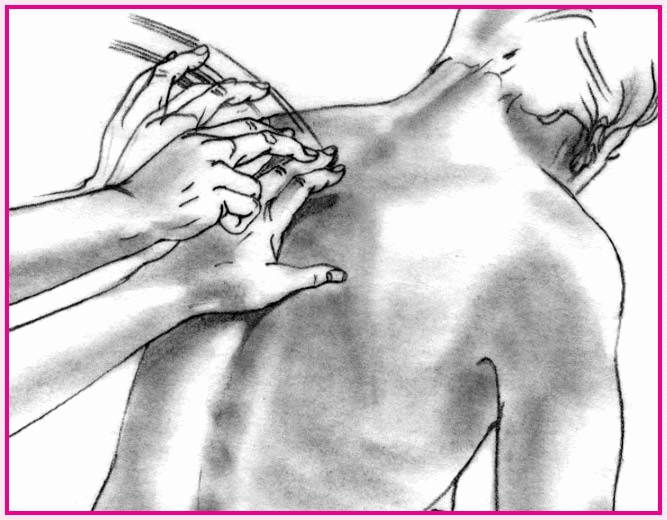

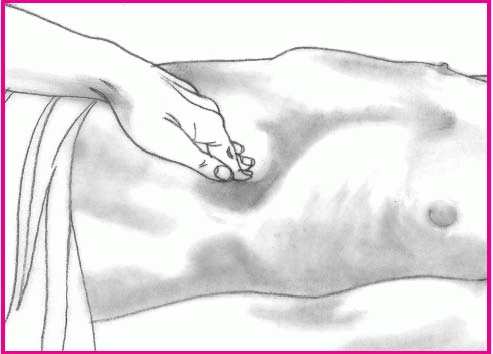

Blunt percussion

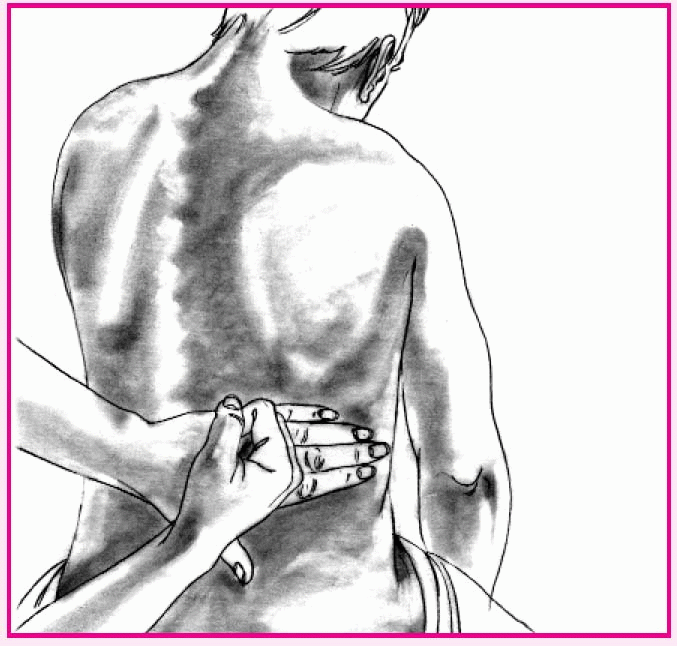

To perform blunt percussion, strike the ulnar surface of your fist against the body surface. Alternatively, use both hands. Place one palm over the area to be percussed. Make a fist with the other hand; use it to strike the back of the first hand (as shown below). Both techniques aim to elicit tenderness—not to create a sound—over organs such as the kidneys. Another blunt percussion method, used in a neurologic examination, involves tapping a rubber-tipped reflex hammer against a tendon to create a reflexive muscle contraction.

Performing palpation

Palpation uses pressure to assess structure size, placement, pulsation, and tenderness. Ballottement, a variation, involves bouncing tissues against the hand to assess rebound of floating structures. Ballottement can be used to assess a mass in a patient with ascites.

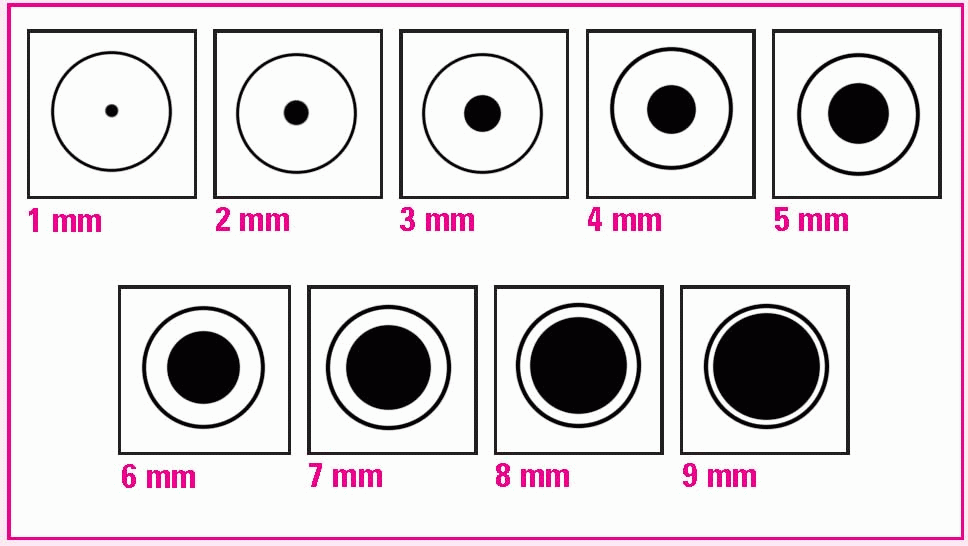

Light palpation

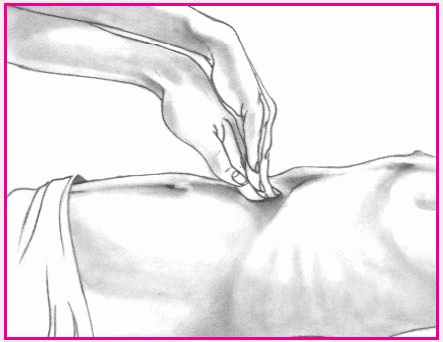

To perform light palpation, press gently on the skin, indenting it 1½″ to 3½″ (4 to 9 cm) (as shown at right). Use the lightest touch possible; too much pressure blunts your sensitivity. Close your eyes to concentrate on feeling.

Deep palpation

To perform deep palpation, indent the skin about 1½″ (4 cm). Place your other hand on top of the palpating hand to control and guide your movements (as shown at right). To perform deep palpation that allows you to pinpoint an inflamed area, push down slowly and deeply, then lift your hand away quickly. If the patient complains of increased pain as you release the pressure, you have identified rebound tenderness.

Use both hands (bimanual palpation) to trap a deep, hard-to-palpate organ (such as the kidney or spleen) or to fix or stabilize an organ (such as the uterus) while palpating with the other hand.

Light ballottement

To perform light ballottement, apply light, rapid pressure from quadrant to quadrant of the patient’s abdomen. Keep your hand on the surface of the skin to detect tissue rebound (as shown at right).

Deep ballottement

To perform deep ballottement, apply abrupt, deep pressure; then release, but maintain contact (as shown at right).

Assessing mental status

To screen for disordered thought processes, ask these questions. An incorrect answer to any question may indicate the need for a complete mental status examination.

Question |

Function screened |

|---|

What’s your name? |

Orientation to person |

What’s your mother’s name? |

Orientation to other people |

What year is it? |

Orientation to time |

Where are you now? |

Orientation to place |

How old are you? |

Memory |

When were you born? |

Remote memory |

What did you have for breakfast? |

Recent memory |

Who’s the President of the United States? |

General knowledge |

Can you count backward from 20 to 1? |

Attention span and calculation skills |

Comparing delirium and dementia

This chart highlights distinguishing characteristics of delirium and dementia.

Clinical feature |

Delirium |

Dementia |

|---|

Onset |

Acute, sudden |

Gradual |

Course |

Short, diurnal fluctuations in symptoms; worse at night, in darkness, and on awakening |

Lifelong; symptoms progressive and irreversible |

Progression |

Abrupt |

Slow but uneven |

Duration |

Hours, to less than 1 month; seldom longer |

Months to years |

Awareness |

Reduced |

Clear |

Alertness |

Fluctuates from lethargic to hypervigilant |

Generally normal |

Attention |

Decreased |

Generally normal |

Orientation |

Generally impaired, but reversible |

May be impaired as disease progresses |

Memory |

Recent and immediate, impaired |

Recent and remote impaired |

Thinking |

Disorganized, distorted, fragmented; incoherent speech, either slow or accelerated |

Difficulty with abstraction; thoughts impoverished; judgment impaired; words difficult to find |

Perception |

Distorted: illusions, delusions, and hallucinations; difficulty distinguishing between reality and misperceptions |

Misperceptions usually absent |

Speech |

Incoherent |

Dysphasia as disease progresses; aphasia |

Psychomotor behavior |

Variable: hypokinetic, hyperkinetic, and mixed |

Normal; may have apraxia |

Sleep and wake cycle |

Altered |

Fragmented |

Affect |

Variable affective anxiety, restlessness, irritability; reversible |

Typically superficial, inappropriate, and labile; attempts to conceal deficits in intellect; possible personality changes, aphasia, agnosia; lack of insight |

Mental status testing |

Distracted from task; numerous errors |

Failings highlighted by family; frequent “near miss” answers, struggles with test, great effort to find an appropriate reply; frequent requests for feedback on performance |

Neurologic stages of altered arousal

This table highlights the six stages of altered arousal. An alert patient responds to voice and has purposeful movement and appropriate spontaneous activity.

Stage |

Manifestations |

|---|

Confusion |

• Loss of ability to think rapidly and clearly

• Impaired judgment and decision making |

Disorientation |

• Beginning loss of consciousness

• Disorientation to time progressing to disorientation to place

• Impaired memory

• Lack of recognition of self (last symptom) |

Lethargy |

• Limited spontaneous movement or speech

• Easily aroused by normal speech or touch

• Possible disorientation to time, place, or person |

Obtundation |

• Mild to moderate reduction in arousal

• Limited responsiveness to environment

• Ability to fall asleep easily without verbal or tactile stimulation

• Minimum response to questions |

Stupor |

• State of deep sleep or unresponsiveness

• Arousable with difficulty (motor or verbal response only to vigorous and repeated stimulation)

• Withdrawal or grabbing response to stimulation |

Coma |

• Lack of motor or verbal response to external environment or stimuli

• No response to noxious stimuli such as deep pain

• Can’t be aroused by any stimulus |

Glasgow Coma Scale

A decreased score in one or more categories may signal an impending neurologic crisis. The best response is scored.

Test |

Score |

Patient’s response |

|---|

Eye opening |

Spontaneously |

4 |

Opens eyes spontaneously |

To speech |

3 |

Opens eyes to verbal command |

To pain |

2 |

Opens eyes to painful stimulus |

None |

1 |

Doesn’t open eyes in response to stimulus |

Motor response |

Obeys |

6 |

Reacts to verbal command |

Localizes |

5 |

Identifies localized pain |

Withdraws |

4 |

Flexes and withdraws from painful stimulus |

Abnormal flexion |

3 |

Assumes a decorticate position |

Abnormal extension |

2 |

Assumes a decerebrate position |

None |

1 |

Doesn’t respond; just lies flaccid |

Verbal response |

Oriented |

5 |

Is oriented and converses |

Confused |

4 |

Is disoriented and confused |

Inappropriate words |

3 |

Replies randomly with incorrect words |

Incomprehensible |

2 |

Moans or screams |

None |

1 |

Doesn’t respond |

Total score |

|

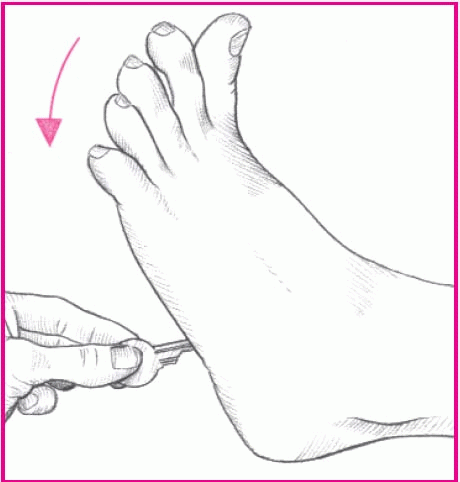

Babinski’s reflex

Stroking the lateral aspect of the sole of the foot with a thumbnail or another moderately sharp object normally elicits flexion of all toes (a negative Babinski’s reflex), as shown below left. In a positive Babinski’s reflex, the great toe dorsiflexes and the other toes fan out, as shown below right.

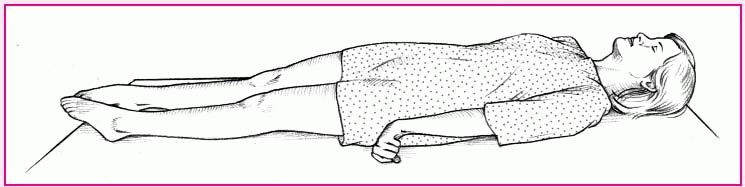

Decerebrate and decorticate postures

Decerebrate

The arms are adducted and extended, with the wrists pronated and the fingers flexed. The legs are stiffly extended, with plantar flexion of the feet. Condition results from damage to upper brain stem.