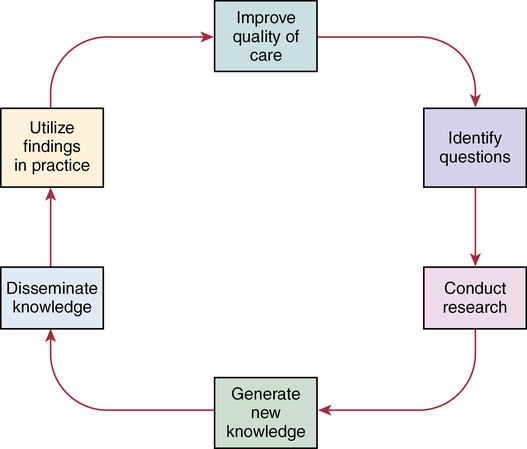

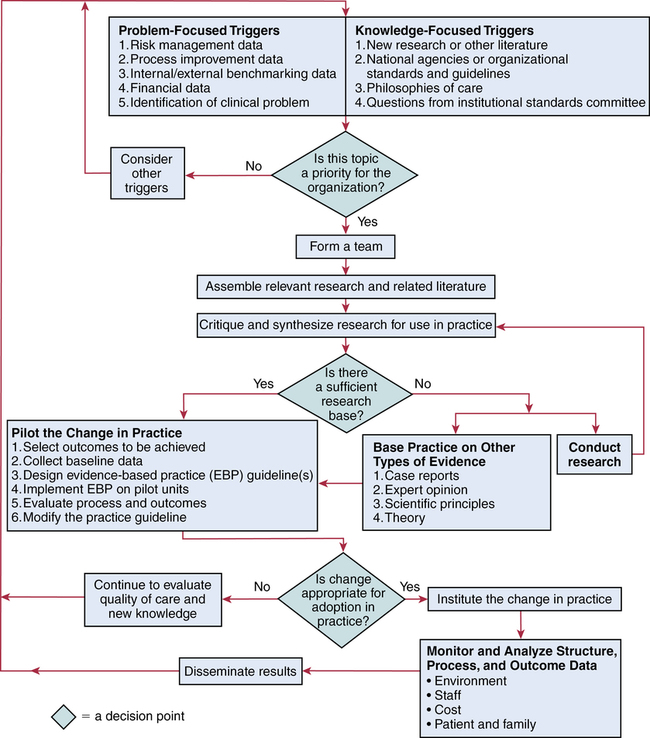

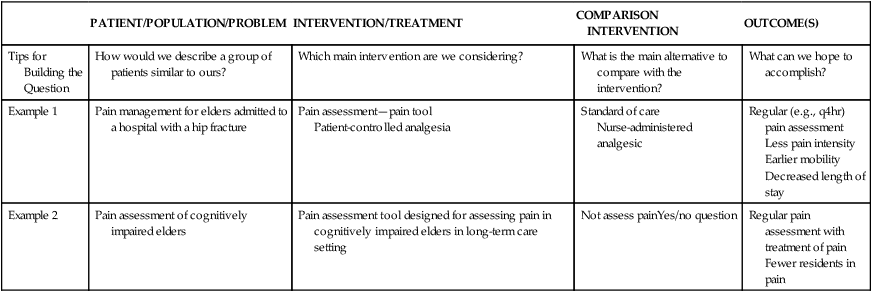

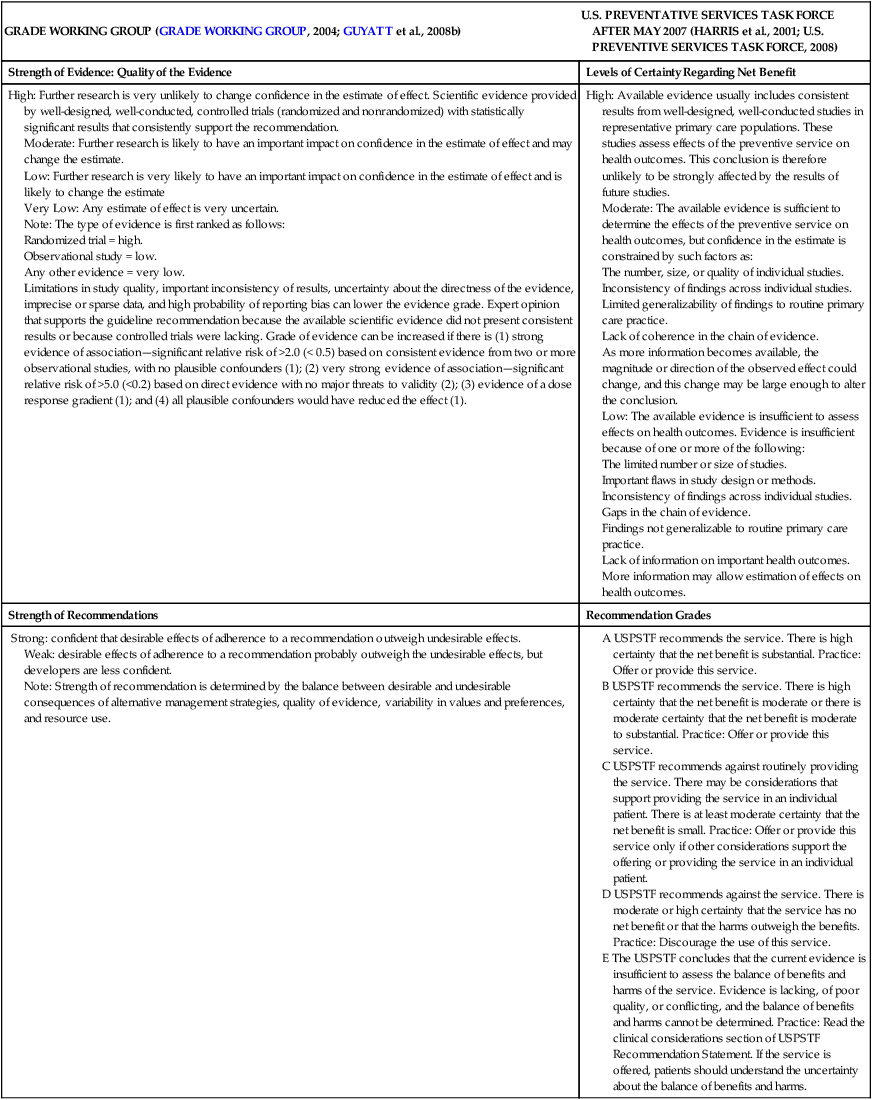

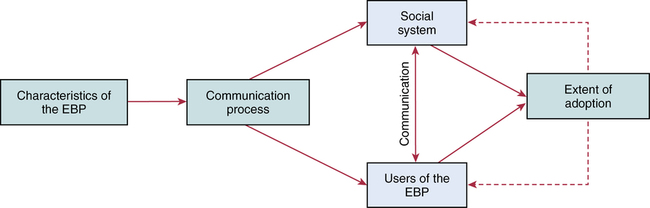

CHAPTER 20 After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following: • Differentiate among conduct of nursing research, research utilization, and evidence-based practice. • Describe the steps of evidence-based practice. • Identify barriers to implementing evidence-based practice. • Describe strategies for implementing evidence-based practice changes. • Identify steps for evaluating an evidence-based change in practice. • Use research findings and other forms of evidence to improve the quality of care. Go to Evolve at http://evolve.elsevier.com/LoBiondo/ for review questions, critiquing exercises, and additional research articles for practice in reviewing and critiquing. Evidence-based health care practices are available for a number of conditions. However, these practices are not always implemented in care delivery settings. Variation in practices abound, and availability of high-quality research does not ensure that the findings will be used to affect patient outcomes (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2008; Institute of Medicine, 2001). The use of evidence-based practices is now an expected standard as demonstrated by recent regulations from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regarding not paying for nosocomial events such as injury from falls, Foley catheter-associated urinary tract infections, and stage 3 and 4 pressure ulcers. These practices all have a strong evidence base and when enacted, can prevent these nosocomial events. However, implementing such evidence-based safety practices is a challenge and requires use of strategies that address the systems of care, individual practitioners, senior leadership, and, ultimately, changing health care cultures to be evidence-based practice environments (Leape, 2005). Translation of research into practice (TRIP) is a multifaceted, systemic process of promoting adoption of evidence-based practices in delivery of health care services that goes beyond dissemination of evidence-based guidelines (Berwick, 2003; Rogers, 2003; Titler & Everett, 2001). Dissemination activities take many forms, including publications, conferences, consultations, and training programs, but promoting knowledge uptake and changing practitioner behavior requires active interchange with those in direct care (Scott et al., 2008; Titler et al., 2008).This chapter presents an overview of evidence-based practice, and the process of applying evidence in practice to improve patient outcomes. The relationships among conduct, dissemination, and use of research are illustrated in Figure 20-1. Conduct of research is the analysis of data collected from subjects who meet study inclusion and exclusion criteria for the purpose of answering research questions or testing hypotheses. Traditionally, the conduct of research has included dissemination of findings via research reports in journals and at scientific conferences. Evidence-based practice is the conscientious and judicious use of current best evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values to guide health care decisions (Sackett et al., 2000). When enough research evidence is available, practice should be guided by research evidence in conjunction with clinical expertise and patient values. In some cases, however, a sufficient research base may not be available, and health care decision making is derived principally from nonresearch evidence sources such as expert opinion and scientific principles. As illustrated in Figure 20-1, application of research findings in practice may not only improve quality care but create new and exciting questions to be addressed via conduct of research. Multiple models of evidence-based practice and translation science are available. Common elements of these models are syntheses of evidence, implementation, evaluation of the impact on patient care, and consideration of the context/setting in which the evidence is implemented. For a summary of models, the review by Grol and colleagues (2007) is recommended. An overview of the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice as an example of an evidence-based practice model is illustrated in Figure 20-2. This model has been widely disseminated and adopted in academic and clinical settings (Titler et al., 2001). In this model, knowledge- and problem-focused “triggers” lead staff members to question current nursing practice and whether patient care can be improved through the use of research findings. If, through the process of literature review and critique of studies, it is found that there is not a sufficient number of scientifically sound studies to use as a base for practice, consideration is given to conducting a study. Findings from such studies are then combined with findings from existing scientific knowledge to develop and implement these practices. If there is insufficient research to guide practice, and conducting a study is not feasible, other types of evidence (e.g., case reports, expert opinion, scientific principles, theory) are used and/or combined with available research evidence to guide practice. Priority is given to projects in which a high proportion of practice is guided by research evidence. Practice guidelines usually reflect research and nonresearch evidence and therefore are called evidence-based practice guidelines (see Chapter 11). The Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality Care (Titler et al., 2001) (see Figure 20-2), in conjunction with Rogers’ diffusion of innovations model (Rogers, 2003) provide steps for actualizing evidence-based practice. A team approach is most helpful in fostering a specific evidence-based practice. Knowledge-focused triggers are ideas generated when staff read research, listen to scientific papers at research conferences, or encounter evidence-based practice guidelines published by federal agencies or specialty organizations. This includes those evidence-based practices that CMS expects are implemented in practice and have now based reimbursement of care on adherence to indicators of the evidence-based practices. Examples include treatment of heart failure, community-acquired pneumonia, and prevention of nosocomial pressure ulcers. Each of these topics includes a nursing component, such as discharge teaching, instructions for patient self care, or pain management. Sometimes topics arise from a combination of problem- and knowledge-focused triggers, such as the length of bed rest time after femoral artery catheterization. In selecting a topic, it is essential that nurses consider how the topic fits with organization, department, and unit priorities to garner support from leaders within the organization and the necessary resources to successfully complete the project. Criteria to consider when selecting a topic are outlined in Box 20-1. • How are decisions made in the practice areas where the evidence-based practice will be implemented? • What types of system changes will be needed? • Who is involved in decision making? • Who is likely to lead and champion implementation of the evidence-based practice? • Who can influence the decision to proceed with implementation of the practice? • What type of cooperation is needed from the stakeholders for the project to be successful? An important early task for the evidence-based practice team is to formulate the PICO question. This helps set boundaries around the project and assists in evidence retrieval. This approach is illustrated in Table 20-1 (see Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 19). TABLE 20-1 USING PICO TO FORMULATE THE EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE QUESTION Modified from University of Illinois at Chicago, P.I.C.O. Model for Clinical Questions, www.uic.edu/depts/lib/lhsp/resources/pico.shtml. Once a topic is selected, relevant research and related literature need to be retrieved, including clinical studies, meta-analyses, and existing evidence-based practice guidelines (see Chapters 3 and 11). AHRQ (www.AHRQ.gov) sponsors the Evidenced-Based Practice Centers and a National Guideline Clearinghouse where abstracts of evidence-based practice guidelines are available. Current best evidence from specific studies of clinical problems can be found in an increasing number of electronic databases such as the Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com), the Centers for Health Evidence (www.cche.net), and Best Evidence (www.acponline.org) (see Chapter 3). Once the literature is located, it is helpful to classify the articles as clinical (nonresearch), theory articles, research articles, systematic reviews, and evidence-based practice guidelines. Before reading and critiquing the research, it is useful to read background articles to have a broad view of the topic and related concepts, and to then review existing evidence-based practice guidelines. It is helpful to read articles in the following order: 1. Clinical articles to understand the state of the practice 2. Theory articles to understand the theoretical perspectives and concepts that may be encountered in critiquing studies 3. Systematic reviews and synthesis reports to understand the state of the science 4. Evidence-based practice guidelines and evidence reports There is no consensus among professional organizations or across health care disciplines regarding the best system to use for denoting the type and quality of evidence, or the grading schemas to denote the strength of the body of evidence (Guyatt et al., 2008a; Institute of Medicine, 2011). See Tables 20-2 and 20-3 for grading and assessing quality of research studies. The important domains and elements to include in grading the strength of the evidence are defined in Table 20-4. TABLE 20-2 EXAMPLES OF EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE RATING SYSTEMS A USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. Practice: Offer or provide this service. B USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. Practice: Offer or provide this service. C USPSTF recommends against routinely providing the service. There may be considerations that support providing the service in an individual patient. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. Practice: Offer or provide this service only if other considerations support the offering or providing the service in an individual patient. D USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. Practice: Discourage the use of this service. E The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. Practice: Read the clinical considerations section of USPSTF Recommendation Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms.

Developing an evidence-based practice

Overview of evidence-based practice

Models of evidence-based practice

The iowa model of evidence-based practice

Steps of evidence-based practice

Selection of a topic

Forming a team

PATIENT/POPULATION/PROBLEM

INTERVENTION/TREATMENT

COMPARISON INTERVENTION

OUTCOME(S)

Tips for Building the Question

How would we describe a group of patients similar to ours?

Which main intervention are we considering?

What is the main alternative to compare with the intervention?

What can we hope to accomplish?

Example 1

Pain management for elders admitted to a hospital with a hip fracture

Pain assessment—pain tool

Patient-controlled analgesia

Standard of care

Nurse-administered analgesic

Regular (e.g., q4hr) pain assessment

Less pain intensity

Earlier mobility

Decreased length of stay

Example 2

Pain assessment of cognitively impaired elders

Pain assessment tool designed for assessing pain in cognitively impaired elders in long-term care setting

Not assess painYes/no question

Regular pain assessment with treatment of pain

Fewer residents in pain

Evidence retrieval

Schemas for grading the evidence

GRADE WORKING GROUP (GRADE WORKING GROUP, 2004; GUYATT et al., 2008b)

U.S. PREVENTATIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE AFTER MAY 2007 (HARRIS et al., 2001; U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE, 2008)

Strength of Evidence: Quality of the Evidence

Levels of Certainty Regarding Net Benefit

High: Further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect. Scientific evidence provided by well-designed, well-conducted, controlled trials (randomized and nonrandomized) with statistically significant results that consistently support the recommendation.

Moderate: Further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate

Very Low: Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Note: The type of evidence is first ranked as follows:

Randomized trial = high.

Observational study = low.

Any other evidence = very low.

Limitations in study quality, important inconsistency of results, uncertainty about the directness of the evidence, imprecise or sparse data, and high probability of reporting bias can lower the evidence grade. Expert opinion that supports the guideline recommendation because the available scientific evidence did not present consistent results or because controlled trials were lacking. Grade of evidence can be increased if there is (1) strong evidence of association—significant relative risk of >2.0 (< 0.5) based on consistent evidence from two or more observational studies, with no plausible confounders (1); (2) very strong evidence of association—significant relative risk of >5.0 (<0.2) based on direct evidence with no major threats to validity (2); (3) evidence of a dose response gradient (1); and (4) all plausible confounders would have reduced the effect (1).

High: Available evidence usually includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations. These studies assess effects of the preventive service on health outcomes. This conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies.

Moderate: The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by such factors as:

The number, size, or quality of individual studies.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Limited generalizability of findings to routine primary care practice.

Lack of coherence in the chain of evidence.

As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this change may be large enough to alter the conclusion.

Low: The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of one or more of the following:

The limited number or size of studies.

Important flaws in study design or methods.

Inconsistency of findings across individual studies.

Gaps in the chain of evidence.

Findings not generalizable to routine primary care practice.

Lack of information on important health outcomes.

More information may allow estimation of effects on health outcomes.

Strength of Recommendations

Recommendation Grades

Strong: confident that desirable effects of adherence to a recommendation outweigh undesirable effects.

Weak: desirable effects of adherence to a recommendation probably outweigh the undesirable effects, but developers are less confident.

Note: Strength of recommendation is determined by the balance between desirable and undesirable consequences of alternative management strategies, quality of evidence, variability in values and preferences, and resource use.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Developing an evidence-based practice

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access