Description and critical reflection of empiric theory

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

We converse with one another of knowledge, research, assumptions and so forth, overconfident that we understand.

Norma Koltoff (1967, p. 122)

After theories are developed, the questions “What is this?” and “How does it work?” can be asked. These questions stimulate the development of empiric theory and serve as an organizing framework for deliberately examining it. The processes of describing and critically reflecting theory address these questions and lead to a clearer understanding of the nature of a theory. This is important if you are going to use a theory in research processes or practice.

The opening quote from Norma Koltoff supports the imperative to carefully examine the meaning of a theory when it is used to guide nursing practice and knowledge development. When you read a particular theory that has the potential to guide your research or practice, it is reasonable to believe that you understand what it means. To a certain extent, you likely do grasp much of its meaning, but the possibility exists that you are inserting meanings, making assumptions, or creating purposes for its use that might not be consistent with the theory. For example, suppose you are working in oncology and have an interest in comfort theory as a way to help people who are going through chemotherapy. As you read theory that addresses the nature of comfort, what enhances comfort, and the projected outcomes of comfort for the persons you care for, it is important to clearly understand what the theorist means by the term comfort. For example, knowing what the theorist means as well as understanding the underlying assumptions about comfort that the theorist has made are important for judging whether the theory will be useful in your practice. If comfort as the theorist describes it is not even possible for persons in the midst of chemotherapy, then the theory may not be useful to you at all. If the theorist assumes that comfort can be achieved but, in your situation, individuals are destined to remain uncomfortable, then the theory may not be useful to you.

The processes of description and critical reflection can be used to scrutinize theory to determine not only if it is useful for your purposes but also if it can be modified to be useful. Just because a theory might not totally fit your situation does not mean that it cannot be used to guide care. What is critical is knowing how the theory does and does not reflect your situation so that decisions about its use can be deliberatively made. For example, if the definition of comfort proposed in a theory is not exactly appropriate for your situation but the assumptions and the other features of the theory are, you may rightfully decide that the theory could be used to promote comfort in a way that is appropriate for persons who are receiving chemotherapy.

When you are serious about using a theory for clinical practice or for guiding research, it is critically important to carefully examine it and to not just assume that you understand the nature of the theory. Without careful examination, care decisions guided by the theory will be less than effective, and research outcomes that are grounded in or that extend the theory will likely be flawed. In addition, if the theory is not carefully examined and understood in relation to the purpose for which it is used, it remains underdeveloped with regard to its usefulness for the discipline of nursing. It is through the processes of description and critical reflection that disciplinary theory is both evaluated and refined.

The definition of empiric theory that we use in this text, as stated here, points to the elements of a theory that can form the basis for describing what the theory is all about. Our definition is as follows:

Theory: A creative and rigorous structuring of ideas that projects a tentative, purposeful, and systematic view of phenomena.

The descriptive components that this definition suggests include the following:

What is this? the description of theory

Describing a theory is a process of posing questions about the components of the theory suggested by the previous definition and then responding to the questions with your own reading or interpretation of the theory. Some elements will seem clear, some will depend on tentative interpretations, and some will remain unclear. Despite ambiguities, the process of describing theory creates a description that can then form the basis for critical reflection. This chapter focuses on theory as a form of empiric knowledge to be described and critically reflected upon. However, many of the questions that we propose to describe and reflect theory could be used in relation to other forms of empiric knowledge as well.

What is the purpose of this theory?

The general purpose of a theory is important because it specifies the context and situations in which the theory is useful. Purpose can be approached initially by asking the following: “Why was this theory formulated?” The responses to this question provide information that pertains to theoretic purposes.

Some purposes are specific to the clinical practice of nursing. In these theories, the concepts of the theory include nursing actions and behaviors that contribute to the purpose. Pain alleviation and restored self-care ability are examples of purpose that require clinical practice and suggest that nursing actions are part of the theory. Note that these purpose statements have a value orientation of alleviation and restoration. These ideas imply change toward a certain goal rather than just change for the sake of change. Such value connotations are important to notice when describing the purpose of a theory.

Some purposes may not require the direct clinical practice of nursing but are useful for understanding phenomena that occur in the context of nursing practice. These purposes can contribute to the achievement of practice purposes, or they may not be directly relevant to practice goals. For example, consider a theory with the central purpose of explaining the variables that affect blood flow velocity in the skin. Clinical practice is not necessary to explain blood flow velocity, but a theory with this purpose might be linked to a theoretic explanation of how blood flow velocity influences the incidence of decubiti or the extent of peripheral neuropathy in people with diabetes. A theory that explains skin blood flow velocity and the factors that affect it might have the potential to help practitioners prevent skin breakdown and peripheral neuropathy.

Theoretic purposes that do not require direct clinical nursing actions but that are of concern to nursing also may involve professional issues in nursing. For example, the purpose of an empiric theory might be to describe the features of organizations that empower nurses. This valued and necessary purpose is not directly related to the specific nursing actions of giving care, but it is certainly useful for changing practice.

It is important to clarify whether purposes are embedded in the theoretic structure or if they are reasonable extensions of the theory. For example, consider a theory of mother–infant attachment that links together the following concepts: (1) the birth or adoption experience, (2) maternal support systems, (3) the degree of bonding, and (4) healthy infant development. The linkages are formed in a way that suggests that maternal attachment is influenced by the nature of the birth or adoption experience, which determines the extent of maternal support and bonding; it goes on to suggest that these features, if positive, encourage healthy infant development. In this example, healthy infant development is an example of a clinical outcome or purpose that is structured within the theory.

Suppose the theorist stated that the purpose of the theory was the quality of life of the family unit, but the theorist did not explain how the concepts within the theory interrelate to create a certain quality of life. Quality of life as a purpose would constitute an extension of the theory because the concept is not located within the structure of the theory. Purposes that are embedded within the structure of the theory are usually explicit. Purposes that are reasonable extensions of the theory are important for understanding the clinical usefulness of the theory, although they are not clearly linked to the central concepts within the theory. Often purposes that are extensions of theory are linked to the concepts and structures of the theory by implicit assumptions. Purposes outside of the context of the theory also suggest directions for the further development of the theory. In the example that was just cited, research or logical reasoning would be indicated that links healthy infant development with quality-of-life indicators.

Purposes within a theory may be found for different individuals or groups of individuals who might use or benefit from the use of the theory. For example, if a theory is developed to address the clinical goal of alleviating pain, the theory can be examined for purposes that are appropriate for the individual nurse, the physician, the person receiving care, and that person’s family. Consider a theory that is developed with a clinical purpose of promoting a high level of wellness. The theoretic purpose for the nurse might be distinctly different from that implied for the person receiving nursing care. The nurse’s purpose might be to design a system that promotes recovery. The purpose for the person receiving care might be to recover and to provide responses that indicate how effective the system is for promoting recovery. Taken together, these two purposes might be viewed as an overall purpose of creating an interactive recovery process.

In addition to whether or not purposes can be found for various individuals who use or are affected by the theory, you can ask questions related to the scope of the theory’s purpose. For example, does the overall purpose focus on an individual, a family, a group, or society in general? An organized society or an expanded collective consciousness is an example of a broad purpose that can be applied to relatively unbounded groups of people. Purposes such as environmental health or political activism may apply to whole communities, or they may be linked to definable groups within those communities. When there are multiple purposes within a theory, the scope of those purposes may vary. You may find narrower-scope purposes for individuals and families and broader-scope purposes for a community. When multiple purposes within a theory are found, if clarity is not compromised, you should be able to order purposes in a hierarchy that flows toward one central purpose.

The following question often arises: “How are purposes to be separated from the concepts of the theory?” Purposes that are part of the matrix of the theory are also concepts of the theory. One approach to identifying which concept is also the central purpose is to describe or designate the concept toward which theoretic reasoning flows. This is related to the structure of the theory. Ask the following questions: “What is the end point of this theory?” and “When is this theory no longer useful?” Responses to these questions provide clues about purpose, and they help to clarify the context in which the theory can be used. In Hall’s (1966) theoretic framework, for example, the theory would cease to be valuable when the client has engaged in self-actualization, and self-actualization may be deemed the overall purpose. This purpose of self-actualization within the structure of Hall’s theoretic framework represents the end point of theoretic reasoning. Within the context of Hall’s theory, self-actualization is a purpose that requires nursing practice. Outside of the context of Hall’s theory, self-actualization is a purpose that is shared with other professions.

What are the concepts of this theory?

Concepts are identified by searching out words or groups of words that represent objects, properties, or events within the theory. You can begin to describe concepts by listing key ideas and tentatively identifying how they seem to interrelate. As you begin to discern relationships, your perception of the key concepts of the theory will become clearer. One initial difficulty that is faced when identifying concepts is determining which concepts are integral to the theory and which are part of some supporting narrative. There is no easy way to deal with this difficulty. By beginning to identify concepts and then deriving interrelationships, decisions can be made about which concepts are central to the theory.

As you identify important theoretic concepts, ask questions about the nature of the concepts and their organization. Is there a major concept with subconcepts organized under it? Are there several major concepts with subconcepts organized under them? Are the concepts singular entities? Are some concepts singular entities and others organized with subconcepts? What are the relationships and interrelationships between and among concepts? Are some concepts mentioned that do not seem to fit the emerging structure? What is the relative scope of the various concepts? After the concepts are identified and questions such as these are addressed, the relationships and structure will begin to emerge.

Other questions deal with the numbers of concepts. How many concepts are there? How many might be considered major concepts? How many are minor concepts? Do not get stuck trying to distinguish between major and minor. Rather, notice whether one concept or a few concepts really stand out as important whereas others seem less important, and consider why this is the case. As you consider the organization and number of concepts, address qualitative features of the concepts as well. Do the concepts represent abstractions of objects, properties, or events? Is it possible to identify what they represent? Are the concepts more empirically grounded, or are they more abstract? What proportion is empirically grounded? What proportion is highly abstract? Are the concepts fairly discrete in meaning, or do several have similar meanings? When similar meanings for concepts exist, do they all seem to express a single idea, or are they different? How are they different? Concepts that are alike may represent either one central idea that is fairly clear or several different images. For example, the concepts of rehabilitation, restoration, and recovery, which share common meanings, may appear in the same theory with similar meanings or with different meanings.

Ask questions about how concrete or abstract the concepts of the theory are. The nature of the concepts in a theory help you to identify how general the theory is or to determine the range of situations in which the theory can be applied. Theories that focus on very broad, abstract concepts (e.g., caring) can be applicable to a very wide range of situations; these theories are sometimes labeled as “grand” theories. When the concepts tend to be descriptive of more specific situations, they tend to be labeled as “middle-range” theories. The labels or categories are not important in themselves; what is important to note is the potential for the concepts to be applied in practice, under what circumstances, and for what purposes.

The nature of the concepts also provides an indication of the potential for the further development of the theory. If the concepts are so abstract that they cannot be defined sufficiently for empiric investigation, then the potential for development as an empiric theory is limited.

When you are addressing the question of a theory’s concepts, the concepts within it must be examined carefully for quantity, character, emerging relationships, and structure. The description of concepts is crucial because the quantity and character of those concepts form an understanding of the purpose of the theory, the structure and nature of theoretic relationships, the definitions, and the assumptions.

What are the definitions in this theory?

A definition is an explicit meaning that is conveyed for a concept. Definitions exist to clarify the nature of the abstraction that the theorist constructs in a way that others can comprehend. Definitions suggest how word representations of an idea (concept) are expressed in experience.

It is often difficult to determine from a listing of key words the concepts that are basic to the theoretic structure and that comprise definitions and assumptions. Carefully reading the theory and relying on your own judgment should provide this information.

Concepts may be defined in a list of definitions, or they may be defined in narrative form in the text but not labeled as definitions. It is not always easy to recognize narratives as definitions, because they are not labeled, and they may contain information that is not directly pertinent to the definition of the concept.

Concept definitions can also be implied by how the theorist uses the conceptual terms in the context. For example, if a theorist uses the concept of wholism but this term is not explicitly defined, you can examine the use of the term and infer the meaning or definition. If the theorist describes various dimensions of wholistic health, then the definition of wholism is akin to “the sum of the parts.” If the theorist does not use parts or dimensions when speaking of wholistic health, then the theorist may be using a definition that is more closely associated with wholism as being more than the sum of the parts.

Because concepts may be defined both explicitly and implicitly, ask the following questions: How are concepts defined? Explicitly? Implicitly? Both? Are implied definitions consistent with explicit definitions? Can common language meanings be taken as the meaning intended? Would a common-language approach lead to differing interpretations of the meanings of the concepts?

Another way to describe definitions is to characterize the extent to which the definitions are general or specific. It is possible for both explicit and implicit meanings to be either general or specific. Assess how general or specific the definitions are. How clearly does the definition suggest an associated empiric experience? Is the definition specific about what a phenomenon is, or does it suggest what its use is? Does it provide possibilities for empiric indicators that represent the phenomenon?

For the abstract concepts that are found in many nursing theories, specific definitions are difficult to formulate. Attempting to prematurely create specific meanings for abstract concepts may interfere with exploring a wide range of possibilities that lead to the discovery of richer or alternative meanings. Definitions that specify general features can conjure very specific mental images of the actual experience. An early definition that is broad and nonspecific encourages the exploration of many possible meanings. General meanings are preferred in broad-scope theories or theories that are not likely to be empirically tested. Most definitions have both specific and general features. Examine how definitions are both specific and general.

After the definitions are identified, ask the following questions: Are similar definitions used for different concepts? Are differing definitions used for the same concept? Are some concepts defined differently than common convention would define them? Are definitions expanded as the narrative proceeds? Is it difficult to judge whether definitions are provided at all? Can definitions fit other terms within or outside of the structure of the theory?

What are the relationships in this theory?

Relationships are the linkages among and between concepts. The nature of relationships in theory may take several forms. Often the relationship statements that are uncovered may be peripheral to the core of the theory.

As concepts are identified, ideas about relationships between them begin to form. Suppose you uncover the following relationship statement: “The individual is composed of three dimensions and is an integral part of the environment.” This statement suggests that the individual is related to an environment and that there are three interrelated subcomponents of the individual.

When a tentative identification of the relationships is made, ask the following questions: Are there concepts that stand alone and that are unrelated to others? Are there concepts that are interrelated with other concepts in several ways and others that are related in only one or two ways? Are there concepts to which several other concepts relate but that, in turn, are not related to other concepts?

The ways in which the relationships emerge provide clues regarding the theoretic purposes and the assumptions on which the theory is based. Some concepts may be linked to the theory by assumptions, which may explain why the concept seems to fit within the matrix of the theory but why a theoretic relationship that contains the concept is not explicitly stated. The theoretic purpose may be represented by the linear relationships of several concepts that converge on one specific concept that, in turn, is not linked to any other concepts; in other words, the linkages end with a specific concept. As linkages between concepts are identified, you can address the nature and character of the relationships. If a relationship is unclear, ask yourself what relationships might be possible and about their associated characters; your ideas can provide clues for the further development of the theory.

Examine the nature of the relationships. Are the relationships basically descriptive, or do they explain something about the phenomenon of interest? Do they create meaning without explaining it? Do they impart understanding? Is there evidence that some relationships are predictive? Relationships within theory that create meaning and impart understanding often link multiple concepts in a loose structure. In other forms of description, concepts are interrelated without elaboration on how and why conceptual relationships are arranged. Concepts that are interrelated often explain how empiric events occur and may provide some detail about how and why concepts interrelate. Prediction implies if-then statements about the occurrence of empiric phenomena. When empirically based predictions of human behavior are shown to be valid, they are usually based on explanation.

The statement “Individuals are composed of three dimensions” is mainly descriptive. It implies that one concept—the individual—is composed of three parts called dimensions. If this sentence was expanded to “The individual is composed of three dimensions that overlap and share common core areas,” then the statement becomes more explanatory. It proposes that each dimension has a shared area with another dimension and that there is an area that is shared by all three. If the phrase interrelated whole were to be added, the “how” of the relationship becomes even clearer because the dimensions must overlap to interrelate the parts of the individual.

Predictions are fairly easy to detect. Sentences that translate into if-then statements are predictive. It is not possible to make an if-then statement out of “The individual is composed of three dimensions,” unless it would be the following, which is implied: “If there are not three dimensions, then it is not an individual.” The statement “The individual is an interrelated whole composed of three dimensions that overlap and share common areas” implies that disturbances in one sphere would be reflected in other spheres. However, this prediction is implied and not explicit.

Suppose the statement read as follows: “Because the individual is an interrelated whole that is composed of three dimensions that overlap and share common areas, a disturbance in one dimension is reflected by disturbances in other dimensions.” This statement is clearly predictive. The distinctions among description, explanation, and prediction are not always clear. Generally, the term description means that the statement projects what something is or the features of its character, whereas explanation suggests how or why it is. Prediction is used to project circumstances that create or alter a phenomenon. Our use of the terms descriptive, explanatory, and predictive when describing the nature of theoretic relationships refers only to the form of the theory. For the purposes of describing a theory, research findings are not required to confirm the nature of relationship statements as descriptive, explanatory, or predictive.

What is the structure of this theory?

The structure of a theory gives overall form to the conceptual relationships within it. The structure emerges from the relationships of the theory. Consider the following two concepts within a theory: the individual and the environment. In one theory, the individual is part of the environment; in another theory, the individual is separate from the environment. In both theories, there is an identifiable relationship between the individual and the environment, but the structure of the relationship differs.

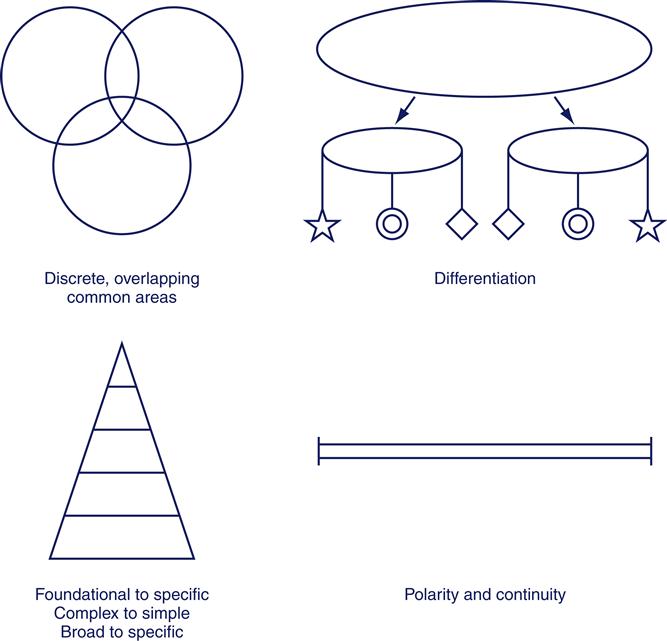

Although your responses to questions about the relationships of the concepts of a theory usually suggest the theory’s form, in some cases they do not. Many theories do not contain a single discernible structure in which all concepts will fit into a coherent, unified network. There may be several—perhaps competing—structures that cannot be reconciled. Determining the structure of the theory will be difficult if the network of relationships is unclear or very complex. Figure 8-1 illustrates a sample of four structural forms and the ideas that they suggest. Some theories may reflect one or more of these structures, whereas others will not. Sometimes individual concepts within theories may be structured in these forms. Structural forms are powerful devices for shaping our perceptions. As you describe a theory, do not expect that it will fit into one of these four structures. It may, but many more structures are possible. Conversely, during the process of theory development, these are only examples of various structures that might evolve during the process of relationship structuring.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree