CHAPTER 15 Delirium and older people in acute care

FRAMEWORK

This chapter uses the data from a study undertaken by the authors to improve practice in prevention, early detection and management of delirium in an acute care hospital environment. The clinical recognition of delirium and differentiation from dementia or confusion was identified as a starting point as literature demonstrated that two-thirds of cases were under-recognised. The authors give a clear account of how participatory action research can change and redesign practice to improve care. The importance of involving staff to claim ownership of the change process cannot be overestimated. Sustaining the change is the challenge and educating new staff to the protocols and gaining skills must be ongoing. [RN, SG]

Introduction

Delirium is a common, potentially preventable and poorly recognised and managed condition, which is experienced by older people before, during and as a consequence of hospital-based acute care. Described as a disorder characterised by an acute decline in attention and cognition, it is under-recognised by health care professionals and, even when symptoms are recognised, delirium is often misidentified and mistreated (Inouye et al 2005). Delirium is a common problem affecting up to 56% of older people admitted to hospital (Anderson 2005; Britton et al 2006).

In this chapter we describe ways health care practitioners decided to redesign their practice to include prevention, early detection and management of delirium in older people admitted to acute care. A 32-bed medical ward of a large acute care hospital in New South Wales, Australia, was the site for a 6-month pilot study. We selected Participatory Action Research (PAR) as the methodology to involve health care practitioners in practice redesign. The university ethics committee approved the pilot study. Eight health care practitioners (participants) joined the PAR group and with three researchers and one high-speed typist, the group numbered 12. The PAR group met on 13 occasions for 1 hour. Although we generated three data sets — researcher’s reflective journals, patient profile audit and PAR group data — in this chapter we talk only about the latter.

Delirium literature to support the PAR process

At the commencement of the study, the researchers (authors) identified and reviewed delirium literature with a focus on best practice guidelines. Databases searched included CINAHL, Medline and Google Advanced Scholar. Selecting only recent (2000–2007) literature pertinent to delirium in older people in general acute care settings, we rejected those deliriums after a surgical episode, whilst in intensive care, during palliation or as a result of medication or alcohol withdrawal. Interested in measurement of delirium, we paid attention to validated tools used for cognitive testing or screening and guidelines presented by the British Geriatric Society and Royal College of Physicians (2006), the Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council (2006) and Harding (2006). It was important to review work from the main international delirium research programs including Inouye and colleagues (Inouye 2004, 2006; Inouye & Charpentier 1996; Inouye et al 1990; Inouye & Bogardus et al 1999; Inouye & Schelesinger et al 1999; Inouye et al 2000, 2001, 2005), Milisen et al (2004, 2005) and McCusker et al (2001, 2002, 2003a, 2003b, 2004). We anticipated sharing these resources with participants, should the group want to take this route as a preliminary step in practice redesign.

Defining delirium

It was important to review some definitions of delirium so they could also be shared with participants. The American Psychiatric Association (1994) defines delirium as:

Further, health care professionals tend of use ‘acute confusion’ as a descriptor for delirium. The problem created is that ‘acute confusion’ contributes to semantic ambiguity and lack of conceptual clarity about delirium (Milisen et al 2005) as it fails to recognise the corresponding decline in physical function. As Rockwood and Bhat (2004) note, the health care professional’s preoccupation with the ‘brain’ as the ‘victim’ in delirium tends to preclude thinking about delirium as a failure of complex systems, and of the body’s response to insult where the brain is affected secondarily.

The features described above are often missed by health care professionals, or if observed, not necessarily connected to delirium (Rockwood & Bhat 2004). We noted that distinguishing delirium’s features from other clinical presentations was not as straightforward in practice as the definitions imply.

Differentiating delirium

In the study reported here, it was important to understand the issues relating to misdiagnosis of delirium and the utility of instruments for the detection of delirium. As noted previously, delirium is often under-recognised in the hospital setting in up to two-thirds of cases (Inouye et al 2001). Further, hypoactive delirium is often not identified (Meagher 2006) and yet it is more prevalent than the hyperactive type.

Clinicians recognise the agitated restless older person with delirium and overlook the older person who is ‘quietly delirious, sitting listless and unnoticed’ (Henschke cited in Harding 2006: iii). In a study by Inouye and her team (2005) from a sample of 115 older patients (>70 years old), 85 were correctly identified by clinicians as having delirium; 45% were hypoactive, 13% were hyperactive, 15% had mixed and 27% were neither hypoactive nor hyperactive. This study points to the high incidence of hypoactive delirium. It is likely that when the older person in acute care presents as drowsy or confused, staff may fail to register the signs of hypoactive delirium; the consequence of missing this diagnosis being serious. Harding’s definition (2006: 2) suggests death may be an outcome of delirium:

In order to differentiate confusion in delirium from other confusional states, Inouye et al (1990, 2005) developed, tested and validated (sensitivity 94–100%; specificity 89–95%) the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The CAM provides a standardised way to accurately detect delirium in a range of settings. In another study designed to compare a chart-based method for detecting delirium with the CAM, Inouye et al (2005) identified several factors including cognitive impairment (such as dementia), severe illness, vision impairment, and high urea nitrogen to creatine ratio that contributed to the misdiagnosis of delirium.

Delirium guidelines, predisposing or risk factors and precipitating factors

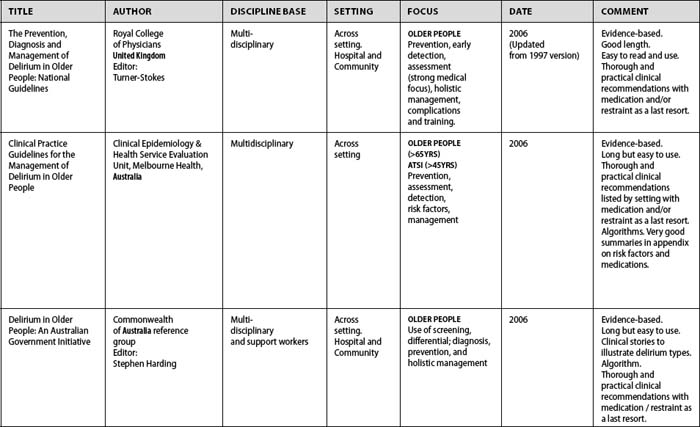

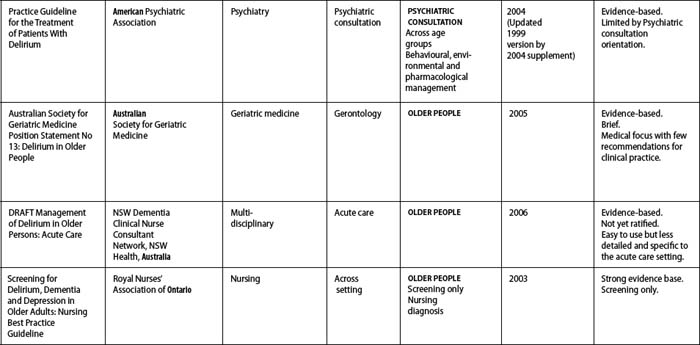

We reviewed the available guidelines (Table 15.1) and selected the validated British Geriatric Society and Royal College of Physicians Guidelines (2006) for the prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people as the best practice resource for the pilot study. The preventive emphasis was appealing as was its multidisciplinary audience, applicability to the acute care context, ease of use and clear link to the literature. We anticipated that the PAR group would consider these guidelines as a reference base. Predisposing and precipitating factors described in the section below are taken from these guidelines.

However, Inouye & Bogardus et al (1999) argue that delirium is rarely caused by a single factor and represents one of the most common potentially preventable adverse episodes for hospitalised older persons. A standardised protocol for the management of six delirium risk factors — cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, dehydration, vision impairment and hearing impairment — is presented with reported reductions in the number and duration of episodes of delirium in hospitalised older adults (Inouye & Bogardus et al 1999). This intervention protocol has been incorporated into a model of care designed to prevent functional and cognitive decline of older persons during hospitalisation and is publicised as the Hospital Elder Life Program (Inouye et al 2000). Of significance is that delirium is the result of multiple factors. A vulnerable older person may have many risk factors and is likely to succumb to delirium after further acute insults (Maher & Almeida 2002).

How common is delirium and what might happen to those who experience it?

As discussed previously, the researchers were aware that delirium was a common condition in acute hospital settings. McCusker et al’s Canadian Medical Research Team reveal that adverse outcomes, including a high risk of death, are some of the consequences of delirium (McCusker et al 2001, 2002, 2003a, 2003b, 2004). Delirium was also shown to be an independent marker for increased mortality among older medical inpatients during the 12 months after hospital admission (McCusker et al 2002). In older medical patients delirium was related to several adverse outcomes including longer mean length of hospital stay (LOS), poor functional status and a need for institutional care (McCusker et al 2003a). In another study delirium was present for up to 1 week in 60% of patients, 2 weeks in 20% of patients, 4 weeks for 15% of patients and more than 4 weeks for 5% of patients (O’Keeffe 2005). We were also aware that discharge and placement decisions are made on ‘current’ functional and cognitive status.

We understood that delirium could be prevented in up to a third of older people. Anderson (2005) highlights the role of prevention in acute care environments and the contribution health care professionals can make to the hospital experience of an older person in an acute care ward. When delirium is not prevented, older people are on a trajectory of higher mortality, institutionalisation, complications such as pressure sores (Roche 2003) and falls (Campbell 1997) and longer periods of stay in the hospital (Anderson 2005; Britton et al 2006; Caplan & Harper 2007; McCusker et al 2002). It became clear to the researchers that to make a difference in delirium health care practice, we needed to focus on its prevention in acute care.

PAR and storytelling

In terms of facilitation of the PAR session, the process of look, think and act was used. In the first few sessions, we looked at the delirium stories and the evidence provided by researchers, and participants were invited to reflect on these. Here we enter a thinking mode. During the first few weeks of meetings it seemed there was a lot of looking, a little thinking and very little action. The focus of this PAR group was on acute care management as the participant stories described patients in hyperactive delirium episodes. But why had the patient’s situation been allowed to sink into a dramatic hyperactive delirium episode warranting acute crisis management? We had registered that prevention and early detection of delirium was best practice and yet this group had not yet shifted to embrace preventive strategies. Mindful that the PAR group sets the agenda for practice redesign, as researchers we wondered about the direction of resultant actions.

Clinicians describe delirium

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Delirium T is often under-recognised in the hospital setting in up to two thirds of cases.

Delirium T is often under-recognised in the hospital setting in up to two thirds of cases. The CAM provides a standardised way to accurately detect delirium in a range of settings.

The CAM provides a standardised way to accurately detect delirium in a range of settings.

Delirium is rarely T caused by a single factor and represents one of the most common potentially preventable adverse episodes for hospitalised older persons.

Delirium is rarely T caused by a single factor and represents one of the most common potentially preventable adverse episodes for hospitalised older persons.