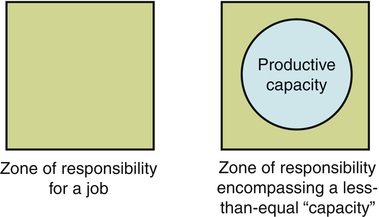

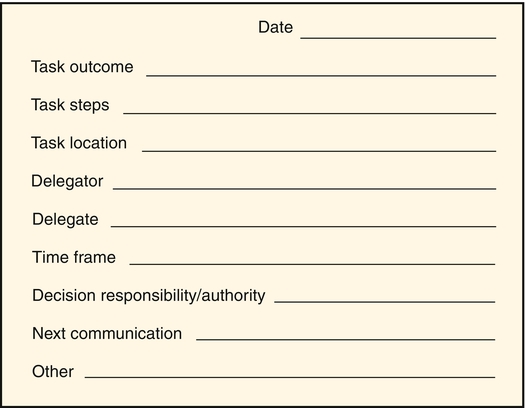

Delegation is a fundamental aspect of every nurse’s job. The effective delegation of work to others is essential in every type of health care setting and organization. Effective delegation skills also are important for managers whose function is to get work done through the efforts of others. For most nursing jobs, the zone of responsibility exceeds one person’s ability to complete all the tasks (Figure 9-1). This is especially true for the care coordination aspects of nursing care management. Nurses need to delegate parts of nursing care delivery to others because, at some point, it becomes impossible to do it all alone. In the 1800’s, delegation was defined by Florence Nightingale (1859) as a critical skill: “But then again to look at all these things yourself does not mean to do them yourself… But can you not insure that it is done when not done by yourself?” (p. 17). Nurses delegate to nurses and paraprofessionals in the health care environment, whether to students, licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs), orderlies or technicians, corpsmen, medication assistants-certified, nursing assistants, or some other form of nurse extender. Weydt (2010) noted that nurses have to understand what patients and families need, then engage the right caregivers in the plan of care to achieve outcomes. Meeting the public’s increasing demand for quality health care that is both accessible and affordable has created a demand for health care providers and maximized the stress on every health care worker. As a result, the identification of which tasks are appropriate to nursing, which of these tasks can be delegated, and to whom they can be delegated is imperative. Delegation issues have become connected to issues of work overload, safety and quality of care, mix of staff, job security and turf, and nurses’ job satisfaction. It has been proposed that delegation of non-nursing tasks also helps reduce health care costs by making more efficient use of nursing time and the facility’s resources (Fisher, 2000). Delegation is at the fulcrum of quality and cost concerns. The NCSBN has developed a number of tools relating to delegation and the roles of licensed nurses and assistive personnel which have been collected into the document Working with Others: A Position Paper (NCSBN, 2005). Key concepts are presented. The NCSBN’s position is presented. The delegation decision making process is presented. There are two helpful decision trees (visual flow charts): delegation to nursing assistive personnel (pp. 11-12) and accepting assignment to supervise unlicensed assistive personnel (pp. 16-17). There is a state-by-state review of statutes and rules, a summary of multiple organizations’ position statements, definitions, and a literature/case law review. Delegation is a decision-making process that requires skillful nurse judgment. The decision to delegate should incorporate critical thinking and sound clinical decision making. The process outlined by the NCSBN (2005) starts with a preparation phase and then has a 4-step process phase. The steps are (1) assess and plan, (2) communication, (3) surveillance and supervision, and (4) evaluation and feedback. In most cases, it is recommended that the nurse delegator and the delegate agree on the task, circumstances, and time frame and then arrange for feedback in which the delegate reports or the delegator evaluates progress toward completion of the task. One way to make certain that both delegator and delegate understand what the task is and how to complete it effectively is to follow up a verbal directive with written instructions so that each person can refer to them later. Figure 9-2 displays a sample delegation tracking form that can be generated by NAP to give to the nurse. As a vehicle for clear communication and verification of expectations and consensus, this form can be modified to be specific to each unit. The task should specify a time frame in which the entire task is to be completed. The decision to delegate needs to be consistent with the nursing process. Thus the nurse needs to ensure appropriate assessment, nursing diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation in a continuous process. In making a decision to delegate nursing tasks, the following five factors can be assessed (American Association of Critical Care Nurses [AACN], 2004): 1. Potential for Harm: The nurse must determine how much risk the activity carries for an individual patient. 2. Complexity of the Task: The more complex the activity, the less desirable it is to delegate. Only an RN should perform activities requiring complex psychomotor skills and expert nursing assessment and judgment. 3. Amount of Problem Solving and Innovation Required: If an uncomplicated activity requires special attention, adaptation, or an innovative approach for a particular patient, it should not be delegated. 4. Unpredictability of Outcome: When a patient’s response to the activity is unknown or unpredictable (depending on how stable the patient is), it is not advisable to delegate that activity. 5. Level of Patient Interaction: Will delegation of a particular activity increase or decrease the amount of time the RN can spend with the patient and patient’s family? Every time a nursing activity is delegated or one or more additional caregivers become involved, a patient’s stress level may increase and the nurse’s opportunity to develop a trusting relationship is diminished. The joint ANA and NCSBN (2006) statement identified nine principles of delegation specific to the RN, including the following: • The RN may delegate elements of care but does not delegate the nursing process itself. • The RN has the duty to answer for personal actions relating to the nursing process. • The RN takes into account the knowledge and skill of any individual to whom the RN may delegate elements of care. The decision of whether to delegate or assign is based on the RN’s judgment concerning the condition of the patient, the competence of all members of the nursing team, and the degree of supervision that will be required of the RN if an element of care is delegated. The RN uses critical thinking and professional judgment when following The Five Rights of Delegation promulgated by the NCSBN (1995) as follows: When determining the right task (element of care) to delegate, the nurse determines whether the element of care falls within the guidelines of established agency policies and procedures, the ANA Code of Ethics, and legal regulations for practice. The nurse then must consider whether the element of care can be delegated to any other staff members. In addition to the five rights, the following three organizational principles are to be considered: 1. The RN acknowledges that there is a relational aspect to delegation and that communication is culturally appropriate and the person receiving the communication is treated respectfully. 2. Chief nursing officers are accountable for establishing systems to assess, monitor, verify, and communicate ongoing competence requirements in areas related to delegation, for both RNs and delegates. 3. RNs monitor organizational policies, procedures, and position descriptions to ensure that the nurse practice act is not violated, working with the state board of nursing if necessary. The five rights can quickly help analyze whether a delegation decision will most likely result in a safe outcome. To facilitate the delegation process in a way that will ensure the client’s personal health needs are addressed and the nurse’s professional goals are achieved, effective communication techniques must be used (Marthaler, 2003). Box 9-1 outlines a personal checklist for the delegator to use for self-evaluation. The essence of the element of care being delegated is often overlooked. Recognition of the potential vulnerability of the client, and thus the presence of an inherently moral element to health care practice, has raised concerns in relation to proper moral regard and respect for clients (Niven & Scott, 2003). This means that nursing judgment about which elements of care are to be delegated requires consideration of the client’s unique individual needs at that point in time. For example, obtaining vital signs on a client who is dying may be a reasonable delegation to NAP. However, because a nurse has spent much time explaining the process of the “do-not-resuscitate” status to the family, a trusting relationship has been established. The client’s or family members’ preferences for treatment/care need to be considered in delegating care activities. Safety is a major facet of delegation, addressed over the years by The Joint Commission’s (TJC) Hospital National Patient Safety Goals. For example, The Joint Commission’s 2007 Patient Safety Goal Requirement 2E, Implement a standardized approach to “hand-off” communications (TJC, 2007), is applicable to delegation. Its provisions include the opportunity to ask and respond to questions. This assists in determining whether delegation can safely occur when a responsible delegator is not physically present. Communication is a major factor in missed care results of delegation. Research has shown no relationship between leadership style and delegation confidence, although there is an interaction between educational preparation and clinical nursing experience (Saccomano & Pinto-Zipp, 2011). There is, however, a bundle of best practices for delegation and supervision skills that includes planning assignments, including NAPs in shift handoffs and rounding, check-in points, evaluation of organizational practices about delegation and supervision, and coaching and mentoring (Gravlin & Bittner, 2010; Hansten & Jackson, 2009). Delegation to unlicensed staff is common in long-term care (LTC) and assisted living settings. Thus delegation is a major strategy for care delivery. UAPs can be certified nursing assistants, personal care workers, or other types of unlicensed personnel. Lightfoot (2011) outlined the following eight principles for RN delegation: 1. Delegate tasks only within the RN’s scope of practice, expertise and knowledge 2. Assess the patient’s condition and stability 3. Only delegate tasks that the UAP is competent to perform and within his/her educational preparation/ability 4. Provide direction and assistance 5. Do not delegate tasks requiring complex nursing skill/judgment 6. Supervise, observe, and monitor UAPs 7. Evaluate the effectiveness of the delegated task

Delegation

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

BACKGROUND

PROCESS OF DELEGATION

Delegation Facets

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Delegation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access