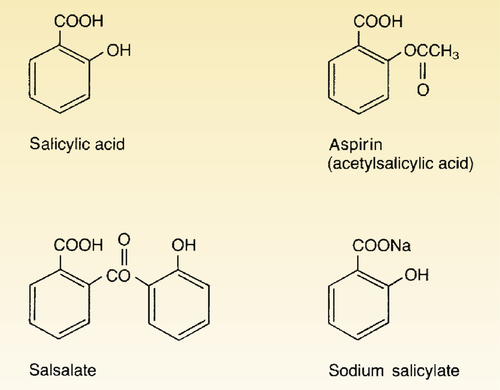

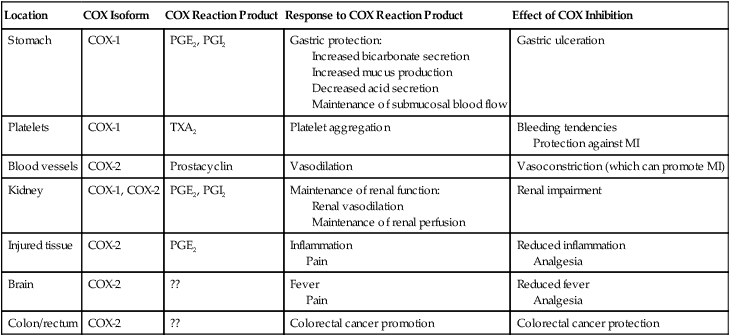

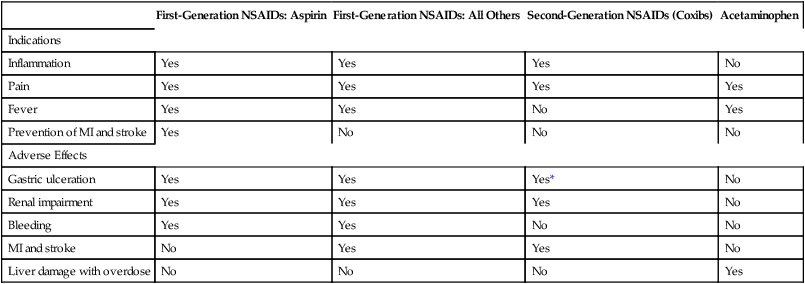

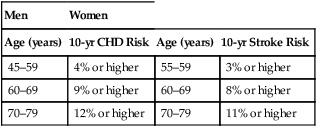

CHAPTER 71 Cyclooxygenase has two forms, named cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2). Cyclooxygenase-1 is found in practically all tissues, where it mediates “housekeeping” chores. Important among these are protecting the gastric mucosa, supporting renal function, and promoting platelet aggregation. In contrast, COX-2 is produced mainly at sites of tissue injury, where it mediates inflammation and sensitizes receptors to painful stimuli. Cyclooxygenase-2 is also present in the brain (where it mediates fever and contributes to perception of pain), the kidney (where it supports renal function), blood vessels (where it promotes vasodilation), and the colon (where it can contribute to colon cancer). Because COX-1 primarily mediates beneficial processes, whereas COX-2 primarily mediates harmful processes, COX-1 has been dubbed the “good COX” and COX-2 the “bad COX.” Some important functions of COX-1 and COX-2 are summarized in Table 71–1. TABLE 71–1 Cyclooxygenase-1 and Cyclooxygenase-2: Functions and Effect of Inhibition Inhibition of COX-1 also has one very beneficial effect: Inhibition of COX-2 (bad COX) results largely in beneficial effects: Inhibition of COX-2 also has two adverse effects: Table 71–2 summarizes the principal indications and adverse effects of the first-generation NSAIDs, second-generation NSAIDs, and acetaminophen. TABLE 71–2 Principal Indications and Adverse Effects of the Four Major Types of Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors *Despite their selectivity for cyclooxygenase-2, coxibs can still cause gastric ulceration, although it may be less than with other NSAIDs. Aspirin belongs to a chemical family known as salicylates. All members of this group are derivatives of salicylic acid (Fig. 71–1). Aspirin is produced by substituting an acetyl group onto salicylic acid. Because of this acetyl group, aspirin is commonly known as acetylsalicylic acid, or simply ASA. Aspirin is an initial drug of choice for rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and juvenile arthritis. Aspirin is also indicated for other inflammatory disorders, including rheumatic fever, tendinitis, and bursitis. The dosages employed to suppress inflammation are considerably larger than dosages used for analgesia or reduction of fever. The use of aspirin and other NSAIDs to treat arthritis is discussed further in Chapter 73. • Ischemic stroke (to reduce the risk of death and nonfatal stroke) • Transient ischemic attacks (to reduce the risk of death and nonfatal stroke) • Acute MI (to reduce the risk of vascular mortality) • Previous MI (to reduce the combined risk of death and nonfatal MI) • Chronic stable angina (to reduce the risk of MI and sudden death) • Unstable angina (to reduce the combined risk of death and nonfatal MI) • Angioplasty and other revascularization procedures (in patients who have a pre-existing condition for which aspirin is already indicated) In addition to these applications, aspirin can be taken by healthy people for primary prevention of MI and stroke. However, benefits differ for men and women. In men, daily aspirin reduces the risk of a first MI, but not the risk of a first ischemic stroke. In women, the opposite applies: daily aspirin reduces the risk of a first ischemic stroke, but not the risk of a first MI. In both sexes, these potential benefits must be weighed against the major risk of aspirin, namely, GI hemorrhage. Hence, to determine the net benefit of primary prevention for any man or woman, we need to determine his or her individual risk for a GI bleed, and compare that risk with his or her individual risk for a cardiovascular (CV) event (ie, the risk for an MI in men, or the risk for ischemic stroke in women).* In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) employed this approach when making the following recommendations for primary prevention: • For men ages 45 to 79 years—Encourage aspirin use when the potential for preventing an MI outweighs the potential harm of a GI hemorrhage. • For women ages 55 to 79 years—Encourage aspirin use when the potential for preventing a stroke outweighs the potential harm of a GI hemorrhage. How do we know when the potential to prevent a CV event outweighs the risk of GI hemorrhage? By using the data in Table 71–3. For example, if the patient is a 65-year-old woman, and her 10-year risk for stroke is 8% or higher, then the benefits of primary prevention are considered to outweigh the risks of a GI bleed. Conversely, if this patient’s 10-year stroke risk were below 8%, then the risks of a GI bleed would outweigh the benefits. How do we calculate 10-year risk for a CV event? Risk for ischemic stroke can be assessed using the online calculator at http://www.westernstroke.org/PersonalStrokeRisk1.xls. Risk for an MI can be assessed using the online calculator at www.mcw.edu/calculators/CoronaryHeartDiseaseRisk.htm. TABLE 71–3 Risk Level at Which CVD Events Prevented Exceed GI Harms CHD = coronary heart disease, CVD = cardiovascular disease. Data are from U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 150:396, 2009. • Increased secretion of acid and pepsin • Decreased production of cytoprotective mucus and bicarbonate • Decreased submucosal blood flow • The direct irritant action of aspirin on the gastric mucosa • A history of peptic ulcer disease • Previous intolerance to aspirin or other NSAIDs • History of alcohol abuse (Alcohol intensifies the irritant effects of aspirin and should not be consumed.) What can we do to prevent ulcers? According to an expert panel—convened in 2008 by the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Heart Association, and the American College of Cardiology—prophylaxis with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is recommended for patients at risk, including those with a history of peptic ulcers, the elderly, and those taking glucocorticoids. Proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole, lansoprazole) reduce ulcer generation by suppressing production of gastric acid. Since many ulcers are caused by infection with Helicobacter pylori (see Chapter 78), the panel recommends that patients with ulcer histories undergo testing and treatment for H. pylori before starting long-term aspirin use. Treatment of NSAID-induced ulcers is discussed in Chapter 78.

Cyclooxygenase inhibitors: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen

Mechanism of action

Location

COX Isoform

COX Reaction Product

Response to COX Reaction Product

Effect of COX Inhibition

Stomach

COX-1

PGE2, PGI2

Gastric protection:

Increased bicarbonate secretion

Increased mucus production

Decreased acid secretion

Maintenance of submucosal blood flow

Gastric ulceration

Platelets

COX-1

TXA2

Platelet aggregation

Bleeding tendencies

Protection against MI

Blood vessels

COX-2

Prostacyclin

Vasodilation

Vasoconstriction (which can promote MI)

Kidney

COX-1, COX-2

PGE2, PGI2

Maintenance of renal function:

Renal vasodilation

Maintenance of renal perfusion

Renal impairment

Injured tissue

COX-2

PGE2

Inflammation

Pain

Reduced inflammation

Analgesia

Brain

COX-2

??

Fever

Pain

Reduced fever

Analgesia

Colon/rectum

COX-2

??

Colorectal cancer promotion

Colorectal cancer protection

Classification of cyclooxygenase inhibitors

First-Generation NSAIDs: Aspirin

First-Generation NSAIDs: All Others

Second-Generation NSAIDs (Coxibs)

Acetaminophen

Indications

Inflammation

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Pain

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Fever

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Prevention of MI and stroke

Yes

No

No

No

Adverse Effects

Gastric ulceration

Yes

Yes

Yes*

No

Renal impairment

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Bleeding

Yes

Yes

No

No

MI and stroke

No

Yes

Yes

No

Liver damage with overdose

No

No

No

Yes

First-generation NSAIDs

Aspirin

Chemistry

Therapeutic uses

Suppression of inflammation.

Suppression of platelet aggregation.

Men

Women

Age (years)

10-yr CHD Risk

Age (years)

10-yr Stroke Risk

45–59

4% or higher

55–59

3% or higher

60–69

9% or higher

60–69

8% or higher

70–79

12% or higher

70–79

11% or higher

Adverse effects

Gastrointestinal effects.