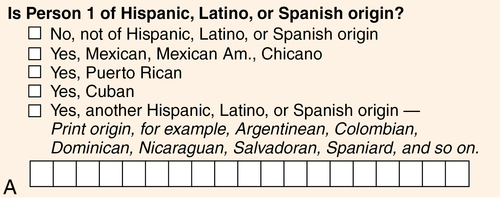

CHAPTER 5 Rick Zoucha and Kimberly Gregg 1. Explain the importance of culturally relevant care in psychiatric mental health nursing practice. 2. Discuss potential problems in applying Western psychological theory to patients of other cultures. 3. Compare and contrast Western nursing beliefs, values, and practices with the beliefs, values, and practices of patients from diverse cultures. 4. Perform culturally sensitive assessments that include risk factors and barriers to quality mental health care that culturally diverse patients frequently encounter. 5. Develop culturally appropriate nursing care plans for patients of diverse cultures. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Globally, how a society views mental health and mental illness has a tremendous impact on how care is allocated, whether individuals access mental health care, and how mental health care is funded. The United States has a relatively enlightened view regarding mental health care, yet we tend to consider it from the perspective of the dominant majority. According to Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—a 2001 report issued by the U.S. Surgeon General—cultural, racial, and ethnic minorities in America have not had the same access to quality mental health services as white Americans (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2001). This report identifies culturally inappropriate services as one of the reasons minority groups in the United States do not receive and/or benefit from needed mental health services. • Culture, race, ethnicity, minority status, and how they are related • Demographic shifts, which make it essential that mental health nurses know how to provide culturally competent care • The impact of cultural worldviews on mental health nursing • Variations in cultural beliefs, values, and practices that affect mental health and care of patients with mental health problems • Barriers to providing quality mental health services to culturally diverse patients • Culturally diverse populations at increased risk of developing mental illness • Techniques for providing culturally competent care to diverse populations Culture comprises the shared beliefs, values, and practices that guide a group’s members in patterned ways of thinking and acting. Culture can also be viewed as a blueprint for guiding actions that impact care, health, and well-being (Leininger & McFarland, 2006). Culture is more than ethnicity and social norms; it includes religious, geographic, socioeconomic, occupational, ability- or disability-related, and sexual orientation–related beliefs and behaviors. Each group has cultural beliefs, values, and practices that guide its members in ways of thinking and acting. Cultural norms help members of the group make sense of the world around them and make decisions about appropriate ways to relate and behave. Because cultural norms prescribe what is “normal” and “abnormal,” culture helps develop concepts of mental health and illness. Acknowledging the inadequacy of describing minority groups according to a single biological race, the U.S. Census Bureau used the 2000 census combined race-ethnicity categorization system for the 2010 census. Respondents are first asked whether they are of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin; if not, they are asked to further identify their race. Federally defined racial groups were expanded from six categories in 2000 to fifteen in 2010 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010). Respondents who do not identify with any of the predefined categories are encouraged to use blank spaces provided to classify their race (Figure 5-1). • Each racial group contains multiple ethnic cultures. There are over 560 Native American and Alaskan tribes and over 40 countries in Asia and the Pacific Islands. The cultural norms of blacks or African Americans whose ancestors were brought to the United States centuries ago as slaves are very different from the norms of those who have recently immigrated from Africa or the Caribbean. Americans of European origin are a diverse group, some of whom have been in the United States for hundreds of years and some of whom are new immigrants. • The Latino-Hispanic group is a cultural group based on a shared language, but all of its members are also members of a racial group or groups (white, black, and/or Native American) and may include Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Cuban Americans, just to name a few. • Persons from the Middle East and the Arabian subcontinent are considered “white” in the classification system. • Although children of multiracial, multicultural, and multiheritage marriages fall into more than one category, their unique identity is not distinguished and sometimes viewed as invisible. In 2043, the United States population is projected for the first time to become a majority-minority nation; that is, no one group will make up the majority (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Non-Hispanic whites will continue to remain the largest single group. A comparison of projected population composition in 2012 and 2060 is provided in Table 5-1. TABLE 5-1 YEAR 2060 POPULATION PROJECTIONS (PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL POPULATION)* The Hispanic and Asian populations are growing at the fastest rates. *Population percentages are rounded to the nearest 1%. Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2012). Population by race and Hispanic origin: 2012 and 2060. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/img/racehispanic_graph.jpg. However, a vast number of people throughout the world have very different philosophical histories and traditions from those of Western cultures (Table 5-2). The Eastern cultures of Asia are based on the philosophical thought of Chinese and Indian philosophers and the spiritual traditions of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. Diverse cultures found among Native Americans, African tribes, Australian and New Zealand aborigines, and tribal peoples on other continents frequently include rich cultural traditions based on deep personal connections to the natural world and the tribe. TABLE 5-2 Copyright © 2002, 2004 by Mary Curry Narayan. Eastern tradition, however, sees the family as the basis for one’s identity, so that family interdependence and group decision making are the norm. Body-mind-spirit are seen as a single entity; there is no sense of separation between a physical illness and a psychological one (Chan et al., 2006). Time is seen as circular and recurring, as in the belief in reincarnation. One is born into an unchangeable fate, with which one has a duty to comply. For the Chinese, disease is caused by fluctuations in opposing forces—the yin-yang energies. The term indigenous culture refers to those people who have inhabited a country for thousands of years and includes such groups as New Zealand Maoris, Australian aborigines, American natives, and native Hawaiians. These groups place special significance on the place of humans in the natural world and frequently manifest a more dramatic difference from Western views (Cunningham & Stanley, 2003). Frequently, the basis of one’s identity is the tribe. There may be no concept of person; instead, a person is an entity only in relation to others. The holism of body-mind-spirit may be so complete that there may be no adequate words in the language to describe them as separate entities. Disease is frequently seen as a lack of harmony of the individual with others or the environment. Diverse cultures have evolved from the three broad categories of worldview described in the previous section. Cultures developed norms consistent with their worldviews and adapted to their own historical experiences and the influences of the “outside” world. Cultures are not static; they change and adjust, although usually very slowly. Each culture has different patterns of nonverbal communication (Table 5-3), etiquette norms (Box 5-1), beliefs and values that shape the culture (Table 5-4), and beliefs, values, and practices that influence how the culture understands health and illness (Table 5-5). For instance, in American culture, eye contact is a sign of respectful attention, but in many other cultures, it may be considered arrogant and intrusive. In Western culture, emotional expressiveness is valued, but in many other cultures, it may be a sign of immaturity. In American culture, independence and self-reliance are encouraged, and the family interdependence valued by other cultures may be seen as a symbiotic relationship or a pathological enmeshment. TABLE 5-3 SELECTED NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION PATTERNS Copyright © 2004 by Mary Curry Narayan. TABLE 5-4 CULTURAL BELIEF AND VALUE SYSTEMS Copyright © 2000, 2004 by Mary Curry Narayan. TABLE 5-5 CULTURAL BELIEFS AND VALUES ABOUT HEALTH AND ILLNESS

Cultural implications for psychiatric mental health nursing

![]() http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/two/five

http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/two/five

Culture, race, ethnicity, and minority status

Demographic shifts in the united states

2012

2060

White, non-Hispanic

63

43

Black, non-Hispanic

13

15

Hispanic (of any race)

17

31

Asian

5

8

All other races

2

3

Worldviews and psychiatric mental health nursing

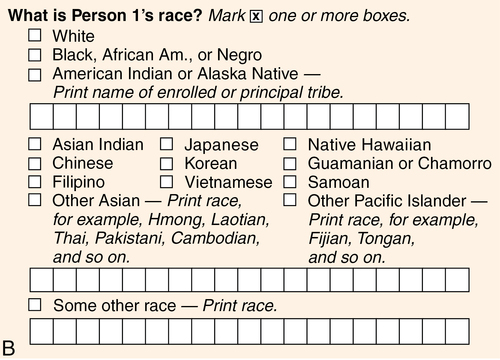

World cultures have grown out of different worldviews and philosophical traditions. Worldview shapes how cultures perceive reality, the person, and the person in relation to the world and to others. Worldview also shapes perceptions about time, health and illness, and rights and obligations in society. The three worldviews compared here are broad categories and generalizations created to contrast some of the themes found in diverse world cultures. They do not necessarily fit any particular cultural group.

WESTERN (SCIENCE)

EASTERN (BALANCE)

INDIGENOUS (HARMONY)

Roman, Greek, Judeo-Christian; the Enlightenment; Descartes

Chinese and Indian philosophers: Buddha, Confucius, Lao-tse

Deep relationship with nature

The “real” has form and essence; reality tends to be stable.

The “real” is a force or energy; reality is always changing.

The “real” is multidimensional; reality transcends time and space.

Cartesian dualism: body and mind-spirit.

Mind-body-spirit unity.

Mind, body, and spirit are considered so united that there may not be words to indicate them as distinct entities.

Self is starting point for identity.

Family is starting point for identity.

Community is starting point for identity—a person is only an entity in relation to others. The self does not exist except in relation to others. There may be no concept of person or personal ownership.

Time is linear.

Time is circular, flexible.

Time is focused on the present.

Wisdom: preparation for the future.

Wisdom: acceptance of what is.

Wisdom: knowledge of nature.

Disease has a cause (pathogen, toxin, etc.) that creates the effect; disease can be observed and measured.

Disease is caused by a lack of balance in energy forces (e.g., yin-yang, hot-cold); imbalance between daily routine, diet, and constitutional type (Ayurveda).

Disease is caused by a lack of personal, interpersonal, environmental, or spiritual harmony; thoughts and words can shape reality; evil spirits exist.

Ethics of rights and obligations:

Based on the individual’s right

Value given to:

Right to decide

Right to be informed

Open communication

Truthfulness

Ethics of care:

Based on promoting positive relationships

Value given to:

Sympathy, compassion, fidelity, discernment

Action on behalf of those with whom one has a relationship

Persons in need of health care considered to be vulnerable and to require protection from cruel truth

Ethics of community:

Based on needs of the community

Value given to:

Contribution to community

Culture and mental health

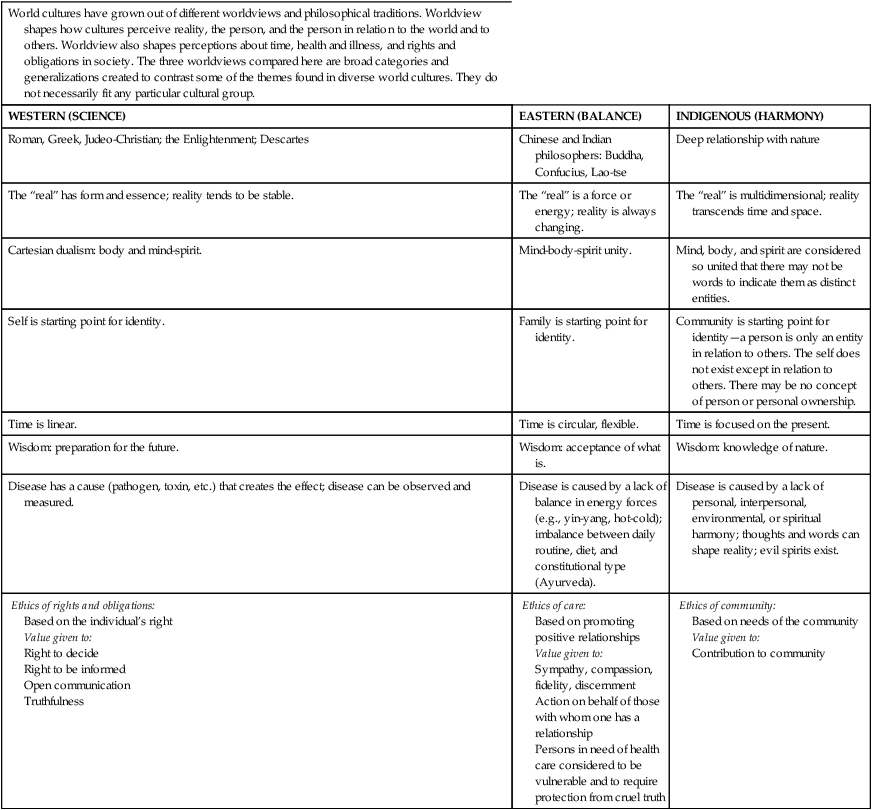

People perceive very strong messages from nonverbal communication patterns; however, the same nonverbal communication pattern can mean very different things to different cultures, as this table indicates. This table does not provide an exhaustive list of possible differences.

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION PATTERN

PREDOMINANT PATTERNS IN THE UNITED STATES

PATTERNS SEEN IN OTHER CULTURES

Eye contact

Eye contact is associated with attentiveness, politeness, respect, honesty, and self-confidence.

Eye contact is avoided as a sign of rudeness, arrogance, challenge, or sexual interest.

Personal space

Intimate space: 0-1½ ft

Personal space: 1½-3 ft

In a personal conversation, if a person enters into the intimate space of the other, the person is perceived as aggressive, overbearing, and offensive. If a person stays more distant than expected, the person is perceived as aloof.

Personal space is significantly closer or more distant than in U.S. culture.

Closer—Middle Eastern, Southern European, and Latin American cultures

Farther—Asian cultures

When closer is the norm, standing very close frequently indicates acceptance of the other.

Touch

Moderate touch indicates personal warmth and conveys caring.

Touch norms vary.

Low-touch cultures—Touch may be considered an overt sexual gesture capable of “stealing the spirit” of another or taboo between women and men.

High-touch cultures—People touch one another as frequently as possible (e.g., linking arms when walking or holding a hand or arm when talking).

Facial expressions and gestures

A nod means “yes.”

Smiling and nodding means “I agree.”

Thumbs up means “good job.”

Rolling one’s eyes while another is talking is an insult.

Raising eyebrows or rolling the head from side to side means “yes.”

Smiling and nodding means “I respect you.”

Thumbs up is an obscene gesture.

Pointing one’s foot at another is an insult.

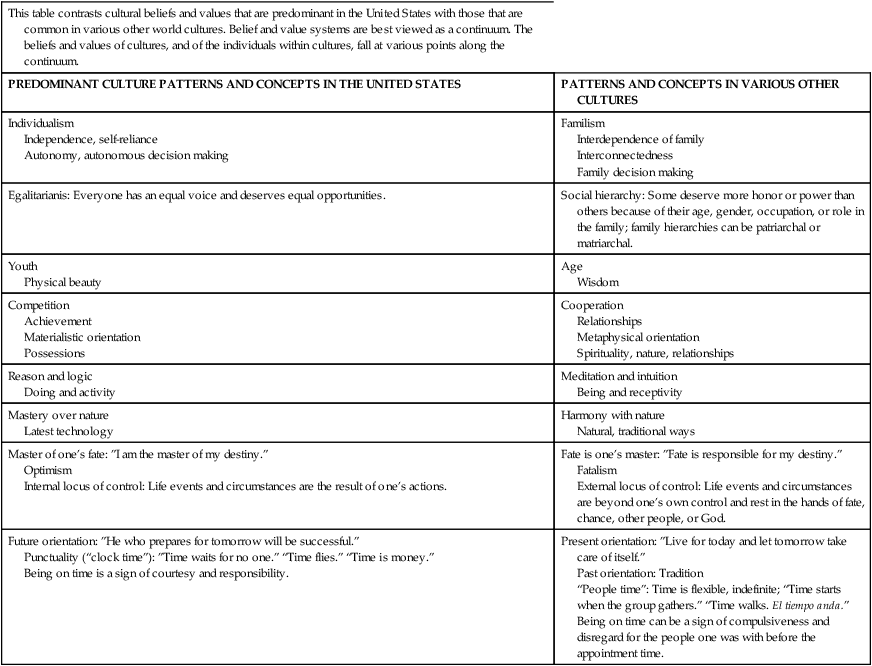

This table contrasts cultural beliefs and values that are predominant in the United States with those that are common in various other world cultures. Belief and value systems are best viewed as a continuum. The beliefs and values of cultures, and of the individuals within cultures, fall at various points along the continuum.

PREDOMINANT CULTURE PATTERNS AND CONCEPTS IN THE UNITED STATES

PATTERNS AND CONCEPTS IN VARIOUS OTHER CULTURES

Individualism

Independence, self-reliance

Autonomy, autonomous decision making

Familism

Interdependence of family

Interconnectedness

Family decision making

Egalitarianis: Everyone has an equal voice and deserves equal opportunities.

Social hierarchy: Some deserve more honor or power than others because of their age, gender, occupation, or role in the family; family hierarchies can be patriarchal or matriarchal.

Youth

Physical beauty

Age

Wisdom

Competition

Achievement

Materialistic orientation

Possessions

Cooperation

Relationships

Metaphysical orientation

Spirituality, nature, relationships

Reason and logic

Doing and activity

Meditation and intuition

Being and receptivity

Mastery over nature

Latest technology

Harmony with nature

Natural, traditional ways

Master of one’s fate: ”I am the master of my destiny.”

Optimism

Internal locus of control: Life events and circumstances are the result of one’s actions.

Fate is one’s master: ”Fate is responsible for my destiny.”

Fatalism

External locus of control: Life events and circumstances are beyond one’s own control and rest in the hands of fate, chance, other people, or God.

Future orientation: ”He who prepares for tomorrow will be successful.”

Punctuality (“clock time”): ”Time waits for no one.” “Time flies.” “Time is money.”

Being on time is a sign of courtesy and responsibility.

Present orientation: ”Live for today and let tomorrow take care of itself.”

Past orientation: Tradition

“People time”: Time is flexible, indefinite; “Time starts when the group gathers.” “Time walks. El tiempo anda.”

Being on time can be a sign of compulsiveness and disregard for the people one was with before the appointment time.

This table contrasts the views typically held by Western nurses and the views about health and illness their patients from diverse cultures may hold.

WESTERN BIOMEDICAL PERSPECTIVE

PERSPECTIVE OF VARIOUS OTHER CULTURES

Health

Absence of disease

Ability to function at a high level

Being in a state of balance

Being in a state of harmony

Ability to perform family roles

Disease causation

Measurable, observable cause that leads to measurable, observable effect

Pathogens, mutant cells, toxins, poor diet

Frequently intangible, immeasurable cause

Lack of balance (yin and yang)

Lack of harmony with environment

Location of disorder

Body

Mind

Whole entity: mind, body, and spirit are completely merged

Disorder causing disease in the person may be in the family or environment

Decisions about care

Made by patient or holder of power of attorney

Goals are autonomy and confidentiality

Truth telling required so patient has information to make decisions

Made by the whole family or family head

Goals are protection and support of patient

Hope should be preserved; patient should be protected from painful truth

Sick role

Sick people should be as independent and self-reliant as possible

Self-care is encouraged; one gets better by “getting up and getting going”

Sick people should be as passive as possible

Family members should “take care of” and “do for” the sick person

Passivity stimulates recovery

Best treatments

Physician-prescribed drugs and treatments

Advanced medical technology

Regaining of lost balance or harmony by counteracting negative forces with positive ones and vice versa

Treatment by folk healers and traditional remedies

Pain

Stoicism valued

Pain described quantitatively

Able to pinpoint location of pain

In cultures in which negative feelings are not expressed freely, pain is kept as silent as possible: Northern European, Asian, Native American

Pain expressed vocally and dramatically

Use of quantitative scales to measure pain is difficult

Pain experienced globally

In cultures in which emotional expression is encouraged, more dramatic pain expression is expected: Southern European, African, Middle Eastern

Ethics

Based on bioethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, justice, and confidentiality

Informed consent requires truthfulness

Based on virtue or community needs

Hope should be preserved, painful truth hidden

Support and care should be provided

Emphasis is on greatest good for the greatest number![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Cultural implications for psychiatric mental health nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access