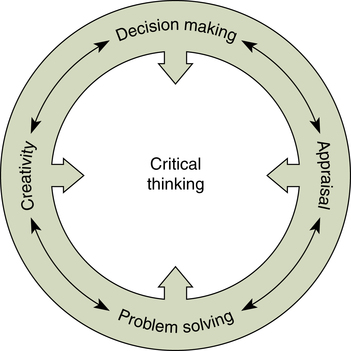

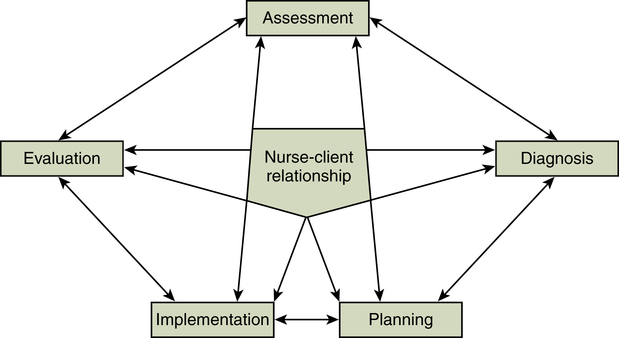

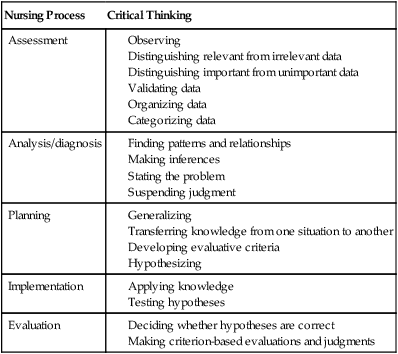

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Describe the components and characteristics of critical thinking. • Understand the relationship of critical thinking to clinical judgment and the nursing process. • Describe the steps of the nursing process and the relationships among those steps. • Discuss nursing activities associated with each step of the nursing process. • Evaluate the utility of the nursing process as a systematic framework for the delivery of nursing care. The ability to process information from multiple sources and make decisions is a fundamental ability of professional nursing practice. Dramatic changes in the health care system and the practice of nursing have occurred during the past decade as a result of an aging population, cost containment efforts, technological advances, increased complexity of clients’ health care needs, decreased average hospital length of stay, and a shift from acute care to community-based care. All of these changes have emphasized the need for professional nurses to think critically in order to provide safe and effective client care to diverse populations. To function effectively in complex, rapidly changing health care environments, nurses must use higher-order thinking skills and apply content knowledge to clinical practice. The critical thinking process provides nurses with the ability to use purposeful thinking and reflective reasoning to examine ideas, assumptions, principles, conclusions, beliefs, and actions in the context of professional nursing practice (Brunt, 2005). Professional nurses must think critically to process complex data from multiple sources and make intelligent decisions in planning, managing, delivering, and evaluating the health care of their clients. Nurses also use their critical thinking skills to reduce health care errors and improve client safety (Fero, Witsberger, Wesmiller, Zullo, & Hoffman, 2008). To become a critical thinker, a nurse must understand the concept of critical thinking; possess or acquire the essential knowledge, skills, and attributes required to think critically; and deliberately apply critical thinking principles in making clinical judgments. This chapter covers both classical and current sources to examine critical thinking, clinical judgment, and the nursing process. Critical thinking, as a concept, has been examined and presented from a variety of perspectives. An early definition, proposed by Watson and Glaser (1964), described critical thinking as the combination of abilities needed to define a problem, recognize stated and unstated assumptions, formulate and select hypotheses, draw conclusions, and judge the validity of inferences. A less prescriptive definition was offered by Ennis (1989), who characterized critical thinking as “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” (p. 4). Paul (1992) stated that critical thinking is a process of disciplined, self-directed rational thinking that “certifies what we know and makes clear wherein we are ignorant” (p. 47). Alfaro-LeFevre (2006) presented critical thinking for nursing as informed, purposeful, and outcome-focused thinking that requires the ability to identify problems, issues, and risks and make judgments based on evidence. Bandman and Bandman (1995) describe critical thinking for nursing as “the rational examination of ideas, inferences, assumptions, principles, arguments, conclusions, issues, statements, beliefs, and actions” (p. 7) and include the following functions: • Discriminating among use and misuse of language • Analyzing the meaning of terms • Formulating nursing problems • Analyzing arguments and issues into premises and conclusions • Examining nursing assumptions • Reporting data and clues accurately • Making and checking inferences based on data • Formulating and clarifying beliefs • Verifying, corroborating, and justifying claims, beliefs, conclusions, decisions, and actions • Giving relevant reasons for beliefs and conclusions • Formulating and clarifying value judgments • Seeking reasons, criteria, and principles that justify value judgments Conflicting viewpoints exist regarding whether critical thinking is subject specific or generalizable (U.S. Department of Education, 1995). Most authors agree that the critical thinking processes are not discipline specific but, rather, are generalizable (Ennis, 1987; Facione, 1990; Paul, 1992; Watson & Glaser, 1964). The same critical thinking skills of interpretation, analysis, inference, and evaluation are applied in different subjects. However, the difference lies in how the critical thinking processes are applied to specific disciplines. For example, professional nurses apply critical thinking skills to client care situations in order to make sound clinical judgments, whereas engineers apply critical thinking skills to business or industrial situations in order to make sound decisions. Meyers (1991) and McPeck (1990) believe that mastery of basic terms, concepts, and methodologies must occur before critical thinking skills can be developed. Ennis (1987) agrees that some familiarity with subject matter is necessary for the development of critical thinking; however, some principles of critical thinking bridge many disciplines and can transfer to new situations. An attempt to define critical thinking by consensus was begun in the late 1980s, and the results became known as the Delphi Report. The Delphi research project used an expert panel of theoreticians representing several disciplines from the United States and Canada to develop a conceptualization of critical thinking from a broad perspective (Facione, 1990). The resulting work described critical thinking in terms of cognitive skills and affective dispositions. The outcome was a definition of critical thinking as the process of purposeful, self-regulatory judgments: an interactive, reflective reasoning process (Facione & Facione, 1996). A critical thinker gives reasoned consideration to evidence, context, theories, methods, and criteria to form a purposeful judgment. At the same time, the critical thinker monitors, corrects, and improves the judgment. The Delphi project produced the following consensus definition from its panel of experts: We understand critical thinking (CT) to be purposeful, self-regulatory, judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which that judgment is based. … CT is essential as a tool of inquiry. As such, CT is a liberating force in education and a powerful resource in one’s personal and civic life. (American Philosophical Association, 1990) The Delphi participants identified core critical thinking skills as interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, and explanation. These critical thinking cognitive skills and subskills are listed in Box 9-1. Scheffer and Rubenfeld (2000) replicated the Delphi study with a panel of 55 nurse educators to obtain a consensus definition of critical thinking for nursing. That study resulted in the identification of 17 dimensions of critical thinking and agreement on the definition of critical thinking for nursing as: Although many areas overlap with the American Philosophical Association’s (1990) Delphi Report definition of critical thinking, some important differences also exist. According to Allen, Rubenfeld, and Scheffer (2004), the dimensions of creativity, intuition, and transforming knowledge that are so crucial to effective clinical practice were not included in the Delphi Report definition. These dimensions emerged in the consensus definition of critical thinking for nursing. Although a universally accepted definition of critical thinking has not emerged, agreement exists that it is a complex process. The variety of definitions helps provide insight into the myriad dimensions of critical thinking. Commonalities in definitions include an emphasis on knowledge, cognitive skills, beliefs, actions, problem identification, and consideration of alternative views and possibilities (Daly, 1998). The definitions presented earlier are summarized for comparison in Table 9-1, and characteristics of critical thinking are listed in Box 9-2. TABLE 9-1 Definitions of Critical Thinking The activities involved in the process of critical thinking include appraisal, problem solving, creativity, and decision making. The interrelationships among these concepts are illustrated in Figure 9-1. These activities are embedded in the critical thinking process in both nursing education and nursing practice. In nursing, critical thinking has often been portrayed as a rational, linear process that is synonymous with clinical judgment, problem solving, and the nursing process (Ford & Profetto-McGrath, 1994; Huckabay, 2009; Jones & Brown, 1993; Kintgen-Andrews, 1991; Wilkinson, 1996). However, some critics believe that the problem-solving emphasis of the nursing process constrains critical thinking because it does not incorporate the creativity and open-mindedness components of critical thinking (Conger & Mezza, 1996; Duchscher, 1999; Jones & Brown, 1993; Miller & Malcolm, 1990). Although critical thinking skills are important components of the nursing process and problem solving, these are not synonymous terms. The nursing process serves as a tool for applying critical thinking to nursing practice. The nurse uses critical thinking throughout the nursing process, by sorting and categorizing data; identifying patterns in the data; drawing inferences; developing hypotheses that are stated in the form of outcomes; testing these hypotheses as care is delivered; and making criterion-based judgments of effectiveness. Therefore critical thinking can distinguish between fact and fiction, providing a rational basis for clinical judgments and the delivery of nursing care. Although an argument can be made that the nursing process constrains critical thinking because of its structured format, general agreement exists that critical thinking skills and subskills are evident throughout the nursing process (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2006). Although the components of the nursing process are described as separate and distinct steps, they become an integrated way of thinking as nurses gain more clinical experience. An overview of critical thinking throughout the nursing process is presented in Table 9-2. A thorough understanding of the nursing process reveals that critical thinking is indeed an integral part of its most effective use. TABLE 9-2 Overview of Critical Thinking Throughout the Nursing Process Modified from Wilkinson, J. M. (2001). Nursing process: A critical thinking approach (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Subsequently, many others have described a “nursing process,” but the model that has withstood the test of time is that developed by Yura and Walsh (1988). They proposed a four-step nursing process model that consisted of assessing, planning, implementing, and evaluating. The current model closely resembles the Yura and Walsh model, but with the addition of a diagnostic component. The five-step nursing process consists of the following elements: • Assessment—gathering and validating client health data, strengths, risks, and concerns • Analysis/diagnosis—processing client data and identifying appropriate nursing diagnoses • Planning—designing strategies to solve identified problems and build on client strengths • Implementation—delivering and documenting the planned care • Evaluation—determining the effectiveness of the care delivered The nursing process is sometimes depicted as a systematic, linear model proceeding from assessment through diagnosis, planning, implementation, and evaluation. It is more appropriately conceptualized as a continuous and interactive model (Figure 9-2), thereby providing a flexible and dynamic approach to client care. This model can accommodate changes in the client’s health status or failure to achieve expected outcomes through a feedback mechanism. The interactive nature of the model with its feedback mechanism permits the nurse to reenter the nursing process at the appropriate stage to collect additional data, restructure nursing diagnoses, design a new plan, or change implementation strategies. This model is consistent with the concept of critical thinking as a continuous reflective process. Further examination of the elements of the nursing process reveals the multiple activities embedded in each step. In the assessment phase, the nurse deliberately and systematically collects data to determine the client’s health, functional status, strengths, and risk factors (Carpenito, 2008). Data collection centers on the use of multiple sources and types of data, a variety of data collection techniques, and the use of reliable and valid measurement instruments. All these elements are critical to building a comprehensive database. Assessment techniques include measurement, observation, and interview. Measurement is used to determine the dimensions of a given indicator (e.g., blood pressure) or to ascertain characteristics such as quantity, size, or frequency. Measurement may require the use of specialized equipment (e.g., stethoscope, thermometer) or specialized assessment tools (e.g., pain scale, depression scale) to assess functional, behavioral, social, or cognitive domains. Data collection by observation requires the use of the senses, including visual observation and tactile (palpation) and auditory techniques (auscultation). Observation provides a variety and depth of data that may be difficult to obtain by other methods. A structured or unstructured interview may be used to obtain information such as a health history and demographic data. A structured interview is commonly used in emergency situations when the nurse needs to gather specific information. An unstructured interview is commonly used in situations in which the nurse wishes to elicit information from the client’s perspective or gain insight to the client’s understanding of a problem. The unstructured interview allows the nurse to use active listening skills while building rapport with the client through the use of an open-ended interview format. These communication techniques are discussed in chapter 8 The use of selected data collection measures and instruments can assist the nurse in compiling a comprehensive database and organizing data into meaningful patterns. Assessment usually begins by taking a nursing history and conducting a physical examination. Many clinical areas have developed nursing history and physical forms specific to the type of agency and the clients served. Regardless of the format, the nursing database should include the following categories of information (Edelman & Mandle, 1994):

Critical Thinking, Clinical Judgment, and the Nursing Process

![]() Introduction

Introduction

![]() Defining Critical Thinking

Defining Critical Thinking

![]() Critical Thinking in Nursing

Critical Thinking in Nursing

SUMMARY OF DEFINITIONS OF CRITICAL THINKING

Author(s)

Definition

Watson and Glaser (1964)

Combination of abilities needed to define problems, recognize assumptions, formulate and select hypotheses, draw conclusions, and judge validity of inferences

Ennis (1989)

Reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do

Paul (1992)

Process of self-disciplined, self-directed, rational thinking that verifies what we know and clarifies what we do not know

The Delphi Report (American Philosophical Association, 1990); Facione, Facione, and Sanchez (1994)

Purposeful, self-regulatory judgments resulting in interpretation, analysis, inference, evaluation, and explanation

Bandman and Bandman (1995)

Rational examination of ideas, inferences, assumptions, principles, arguments, conclusions, issues, statements, beliefs, and actions

Alfaro-LeFevre (2006)

Informed, purposeful, and outcome-focused thinking that uses evidence to make clinical judgments

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE NURSING PROCESS

Nursing Process

Critical Thinking

Assessment

Analysis/diagnosis

Planning

Implementation

Evaluation

![]() The Nursing Process

The Nursing Process

ASSESSMENT

Data Collection Techniques

Data Collection Instruments