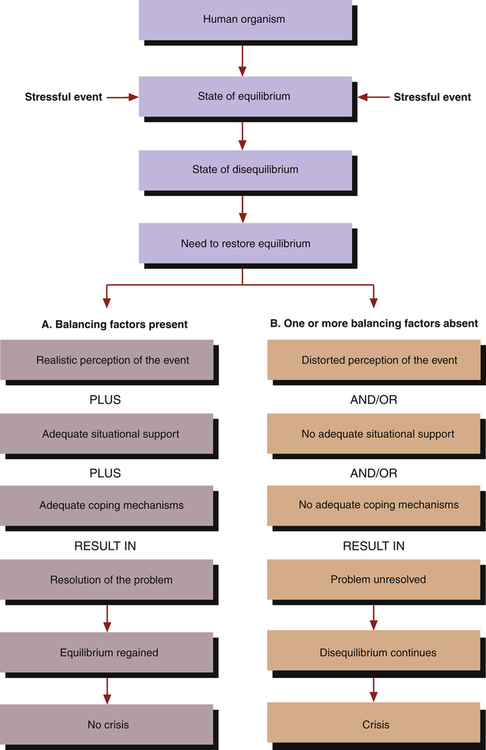

1. Describe a crisis and its characteristics, including crisis responses, types of crises, characteristics of disasters, and crisis intervention. 2. Analyze aspects of the nursing assessment related to crisis and disaster responses. 3. Plan and implement nursing interventions for patients related to their crisis and disaster responses. 4. Develop a patient education plan to cope with crisis. 5. Evaluate nursing care for patients related to their crisis and disaster responses. 6. Describe the settings in which crisis and disaster intervention may be practiced. Stressful events, or crises, are a common part of life. They may be social, psychological, or biological in nature, and there is often little that a person can do to prevent them. As the largest group of health care providers, nurses are in an excellent position to help promote healthy outcomes for people in times of crisis and disaster (Happell et al, 2009). 1. The anxiety activates the person’s usual methods of coping. If these do not bring relief, anxiety increases because coping mechanisms have failed. 2. New coping mechanisms are tried or the threat is redefined so that old ones can work. Resolution of the problem can occur in this phase. However, if resolution does not occur, the person goes on to the last phase. 3. The continuation of severe or panic levels of anxiety may lead to psychological disorganization. In describing the phases of a crisis, it is important to consider the balancing factors shown in Figure 13-1. These include the individual’s perception of the event, situational supports, and coping mechanisms. Successful resolution of the crisis is more likely if the person has a realistic view of the event; if situational supports are available to help solve the problem; and if effective coping mechanisms are present (Aguilera, 1998). The phases of a crisis and the impact of balancing factors are similar to the elements of the Stuart Stress Adaptation Model used in this textbook and described in Chapter 3. However crises are self-limiting. People in crisis are too upset to function at such a high level of anxiety indefinitely. The time needed to resolve the crisis, whether it is a positive solution or a state of disorganization, may be 6 weeks or longer. In addition, the safety felt by all people across the United States was affected. One study found that more than half of the people who lived or worked in New York had some emotional sequelae 3 to 6 months after September 11; however, only a small portion of those with severe responses were seeking treatment (DeLisi et al, 2003). Disaster-precipitated emotional problems can surface immediately, or weeks or even months after the disaster. After the September 11 attack, individuals who lost family members accounted for 40% of mental health visits in the first month but dropped to 5% by 5 months. Uniformed personnel used many more mental health services after the first year (Covell et al, 2006). Researchers have identified several common characteristics of disasters that are particularly important when discussing emotional distress and recovery. These are listed in Box 13-1. Disaster responses usually occur in seven phases. These are described in Table 13-1. Individuals and communities progress through these phases at different rates depending on the type of disaster and the degree and nature of disaster exposure. This progression may not be sequential, because each person and each community is unique in the recovery process. Individual variables such as psychological resilience, social support, and financial resources influence a survivor’s capacity to move through the phases. TABLE 13-1 From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Training manual for mental health and human service workers in major disasters, ed 2, Washington, DC, 2000, U.S. Government Printing Office. It is important for the nurse to remember that culture strongly influences the crisis intervention process, including the communication and response style of the crisis worker. Cultural attitudes are deeply ingrained in the processes of asking for, giving, and receiving help. They also affect the victimization experience, as seen in Box 13-2, so it is essential to understand and respect the sociocultural context of crisis care. Specific cultural factors to be considered in crisis intervention include the following: • Migration and citizenship status • Use of extended family and support systems • Housing and living conditions The first step of crisis intervention is assessment. At this time, data about the nature of the crisis or disaster and its effect on the patient must be collected. From these data an intervention plan will be developed. People in crisis experience many symptoms, including those listed in Box 13-3. Sometimes these symptoms can cause further problems. For example, problems at work may lead to loss of a job, financial stress, and lowered self-esteem. Anger is most common in the “disillusionment phase” noted in Table 13-1. In some cases, it can even pose a danger to the health care responders who have come to assist survivors. Thus, safety issues should be a priority for the nurse in working with patients in crisis. Although the crisis situation is the focus of the assessment, the nurse may identify more significant and long-standing problems. Those individuals with preexisting psychological problems may have more postdisaster health problems. For example, those with serious mental illness will need help in ensuring access to their medications and caregiver stability (Milligan and McGuinness, 2009). • Precipitating event or stressor • Patient’s perception of the event or stressor • Nature and strength of the patient’s support systems and coping resources 1. Self-esteem needs are achieved when the person attains successful social role experience. 2. Role mastery needs are achieved when the person attains work, sexual, and family role successes. 3. Dependency needs are achieved when a satisfying interdependent relationship with others is attained. 4. Biological function needs are achieved when a person is safe and life is not threatened. This process is outlined in the Patient Education Plan for coping with crisis in Table 13-2. The expected outcome of nursing care is that the patient will recover from the crisis event and return to a precrisis level of functioning. A more ambitious expected outcome would be for the patient to recover from the crisis event and attain a higher than precrisis level of functioning and improved quality of life. TABLE 13-2 PATIENT EDUCATION PLAN

Crisis and Disaster Intervention

Crisis Characteristics

Crisis Responses

Situational Crises

PHASE

RESPONSE

Warning or threat phase

Disasters vary in the amount of warning communities receive before they occur from little or no warning to hours or even days of warning. When no warning is given, survivors may feel more vulnerable, unsafe, and fearful of future unpredicted tragedies.

Impact phase

The impact period of a disaster can vary from the slow, low-threat build-up associated with some types of floods to the violent, dangerous, and destructive outcomes associated with tornadoes and explosions. The greater the scope, community destruction, and personal losses associated with the disaster, the greater the psychosocial effects.

Rescue or heroic phase

In the immediate aftermath, survival, rescuing others, and promoting safety are priorities. For some, postimpact disorientation gives way to adrenaline-induced rescue behavior to save lives and protect property. Although activity level may be high, actual productivity is often low. Altruism is prominent among both survivors and emergency responders.

Remedy or honeymoon phase

During the week to months following a disaster, formal governmental and volunteer assistance may be readily available. Community bonding occurs as a result of sharing the catastrophic experience and the giving and receiving of community support. Survivors may experience a short-lived sense of optimism that the help they will receive will make them whole again. When disaster mental health workers are visible and perceived as helpful during this phase, they are more readily accepted and have a foundation from which to provide assistance in the difficult phases ahead.

Inventory phase

Over time, survivors begin to recognize the limits of available disaster assistance. They become physically exhausted because of enormous multiple demands, financial pressures, and the stress of relocation or living in a damaged home. The unrealistic optimism initially experienced can give way to discouragement and fatigue.

Disillusionment phase

As disaster assistance agencies and volunteer groups begin to pull out, survivors may feel abandoned and resentful. The reality of losses and the limits and terms of the available assistance become apparent. Survivors calculate the gap between the assistance they have received and what they will require to regain their former living conditions and lifestyle. Stressors abound—family discord, financial losses, bureaucratic hassles, time constraints, home reconstruction, relocation, and lack of recreation or leisure time. Health problems and exacerbations of preexisting conditions emerge because of ongoing, unrelenting stress and fatigue.

Reconstruction or recovery phase

The reconstruction of physical property and recovery of emotional well-being may continue for years following the disaster. Survivors have realized that they will need to solve the problems of rebuilding their own homes, businesses, and lives largely by themselves and gradually assume the responsibility for doing so. Survivors are faced with the need to readjust to and integrate new surroundings as they continue to grieve losses. Emotional resources within the family may be exhausted and social support from friends and family may be worn thin.

When people come to see meaning, personal growth, and opportunity from their disaster experience despite their losses and pain, they are well on the road to recovery. Although disasters may cause profound life-changing losses,

they also bring the opportunity to recognize personal strengths and to

reexamine life priorities.

Crisis Intervention

Assessment

Precipitating Event

Planning And Implementation

Coping with Crisis

CONTENT

INSTRUCTIONAL ACTIVITIES

EVALUATION

Describe the crisis event.

Ask about the details of the crisis, including the following:

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Crisis and Disaster Intervention

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access