Guided Care, however, was designed to enhance primary care by infusing the operative principles of all seven chronic care innovations outlined in Table 10.1. Thus, Guided Care seeks to make evidence-based, state-of-the-art, chronic care available continuously from teams of professionals that patients trust.

Intervention

In Guided Care, a registered nurse with a Certificate in Guided Care Nursing collaborates with three to five primary care physicians and their office staff to meet the complex needs of 50 to 60 patients with multiple chronic conditions. The Guided Care nurse (GCN) provides eight essential chronic care services that align scientific evidence with patients’ values and preferences (Boyd et al. 2007).

1. Assess the patient at home. The GCN conducts an initial, two-hour, in-home assessment of each patient. The GCN begins by asking the patient to identify his/her highest priorities for optimizing health and quality of life. Using a standardized questionnaire, the nurse evaluates the patient’s medical, functional, cognitive, emotional, psychosocial, nutritional, and environmental status. The GCN inquires about the care the patient receives from family caregiver(s), specialist physicians, and community agencies. The GCN obtains the patient’s signature authorizing the release of medical information and gathers supplemental information about the patient’s health from the medical records at the primary care office.

2. Create an evidence-based comprehensive “Care Guide” and “Action Plan.” Back at the office, the GCN uses the practice’s health information technology (HIT) to merge the patient’s individual assessment data with evidence-based guidelines to create a Preliminary Care Guide (PCG) for managing the patient’s chronic conditions. The GCN then meets with the primary care physician for 20 to 25 minutes to personalize the PCG according to the unique circumstances of the individual patient. Later the GCN discusses the PCG with the patient and family caregiver and modifies it further for consistency with their preferences, priorities, and intentions. The GCN then generates the patient’s Care Guide (CG), which provides a concise, comprehensive summary of the patient’s status, and is a blueprint for the patient’s health care for duration of the patient’s life. The GCN then converts the information contained in CG into a patient-friendly Action Plan, which is written in lay language and displayed prominently in the patient’s home to remind the patient to take prescribed medicines on time, to eat the desired diet, to engage in the recommended physical activities, to self-monitor, to keep appointments with health care providers, and to call the GCN for help when needed.

3. Monthly monitoring. Reminded by alerts HIT, the GCN monitors each patient at least monthly, usually by telephone and sometimes in person when patients visit their primary care physicians, to evaluate adherence to the Action Plan and to detect and address emerging problems promptly. During the practice’s “business hours,” the GCN is also accessible by cell phone to patients and caregivers for problems that emerge between monitoring calls and office visits. When health-related problems arise, the GCN discusses them with the primary care physician, implements appropriate actions, and updates the patient’s Care Guide and Action Plan.

4. Promote patient self-management. Based on the Action Plan, the GCN teaches self-management skills, promotes the patient’s confidence for managing chronic conditions, and encourages the patient to take personal responsibility for his or her health. The GCN uses motivational interviewing to facilitate the patient’s engagement in self-care and to reinforce adherence to the Action Plan. When available, the nurse also refers Guided Care patients to local chronic disease self-management programs (CDSMP). Developed and evaluated at Stanford University, these programs are now available for free or at a nominal cost in many communities in the United States (Lorig & Holman 2003).

5. Coordinate the efforts of all the patient’s health care providers. The GCN coordinates the efforts of the many health care professionals who treat Guided Care patients – in primary care, emergency departments, hospitals, rehabilitation facilities, specialists’ offices, nursing homes, and at home. By monitoring the actions of those providers, the GCN keeps the Care Guide current and complete, and shares it with all involved health care providers.

6. Smooth patient’s transitions between sites of care. The GCN smoothes the patient’s transitions between all sites of care while focusing most intensively on transitions through hospitals. The GCN rounds on patients in the hospital, helps design and execute discharge plans, visits patients at home within two days of discharge, and ensures that patients return to their primary care physicians promptly. The GCN also keeps the primary care physician informed of the patient’s status and updates the patient’s Care Guide and Action Plan to reflect the care received in the hospital.

7. Assess, educate, and support caregivers. For the family or other caregivers, the GCN offers individual assistance in the forms of an initial assessment, information about caregiving and their loved ones’ health conditions, and ad-hoc telephone consultation to address caregivers’ questions and concerns.

8. Facilitate access to community resources. The GCN maintains a database of the resources in the local community that may be helpful to people with chronic conditions and facilitates access to these resources to meet the needs of the patient and family caregiver. For example, the GCN may suggest or help a patient or family caregiver contact a transportation service, Meals-on-Wheels, the Area Agency on Aging, a senior center, an adult day care center, or the Alzheimer’s Association for additional supportive services.

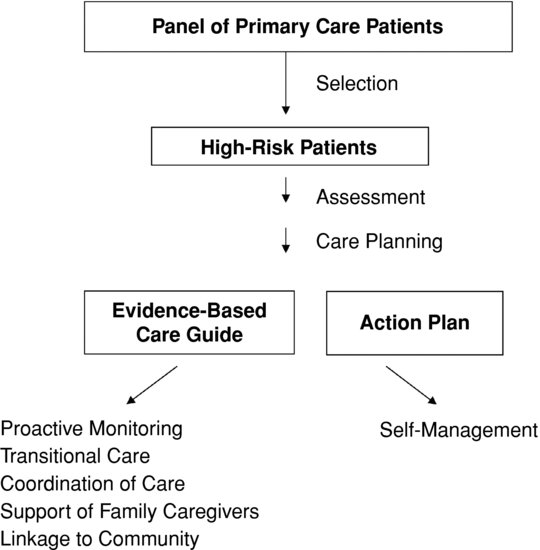

The primary goal of Guided Care is to improve the quality of life for patients. Identifying patients that are most likely to benefit from Guided Care (that is, those with multimorbidity, complex health care needs, and high health care expenditures) is crucial to the cost-effectiveness of the model. Although clinicians are capable of identifying patients with multimorbidity, electronic predictive models can identify such patients more objectively, consistently, and efficiently (Institute for Health Policy Solutions 2005). As shown in Figure 10.1, the 20% to 25% of older patients on the panel who have the highest estimated need for complex health care in the future are selected for Guided Care. No high-risk patients are excluded because of a condition (for example, dementia) or place of residence (such as a nursing home), although some cognitively impaired patients may be unable to fully participate in chronic disease self-management (Boult et al. 2009).

A letter is mailed to eligible patients, notifying them that they are eligible (but not required) to receive Guided Care and that the practice’s GCN will follow up by phone. The GCN calls the patient to provide more details about Guided Care, to answer their questions, to ask whether the patient is interested in receiving Guided Care and, if appropriate, to schedule a time for an in-home assessment. The GCN follows the patients for life, unless the patient moves out of the area or changes primary care physicians (to one who does not provide Guided Care). The typical caseload of a GCN is 50 to 60 patients, each of whom has several chronic health conditions (see Table 10.2).

The GCN interacts with patients both in person and by telephone. The in-home assessment is done in person, and the GCN visits the patient at home within 48 hours following a hospitalization to reconcile medications, to ensure that the patient is following the appropriate regimen, and to address the patient’s and the family’s questions and concerns. The GCN also meets in person with the patient when he/she visits the primary care office for physician appointments.

The GCN contacts the patient by phone for monthly monitoring and coaching sessions about their health and steps they have taken to achieve their goals. During some of these contacts, the patient may, after learning to trust the GCN, admit to having difficulty adhering to certain activities in the Action Plan. The GCN then uses motivational interviewing to help the patient overcome these obstacles by discussing the desired behavioral change as a method for meeting the patient’s goals (for example, walking to the shopping center again, attending a granddaughter’s graduation, and so on). The GCN is also available by cell phone during business hours to address new symptoms, problems, and questions when they arise.

The average amount of time spent by a GCN on specific activities during a typical forty-hour, five-day week are: three and one-half hours assessing new patients and caregivers, eight hours of scheduled monitoring and coaching, four hours coordinating transitions between sites and providers of care, eight hours documenting activities and updating Care Guides and Action Plans, four hours addressing emerging issues with patients and caregivers, three hours communicating with primary care physicians and other providers, one-half hour accessing community resources, one hour supporting family caregivers, and eight hours on other administrative tasks (that is, meetings, traveling to homes/hospitals, responding to e-mail).

Table 10.2 Characteristics of Guided Care Patients

Case studies

Case #1

Mrs. Sheila Johnson is an 86-year-old married woman with a history of hypertension, high cholesterol, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and a knee replacement. Mrs. Johnson has two grown children who live out-of-state and an 82-year-old husband who is in good health and acts as her primary caregiver. They live in a small town with limited access to specialty health care services.

During a recent trip to visit their children, Mrs. Johnson was hospitalized for five days with new diagnoses of congestive heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Returning home, she saw her primary care physician who referred her to a cardiologist in a city 25 miles away. She was started on coumadin and, although anxious about the potential side effect of bleeding, was compliant with the medication regime. After eight months on coumadin, she developed severe bruising in her arm and, against the advice of her cardiologist, Mrs. Johnson stopped the coumadin. Three weeks later, she was hospitalized with a minor stroke caused by the atrial fibrillation. Repeat hospitalizations flagged Mrs. Johnson for Guided Care, and she was discharged home on coumadin with a referral to Karen Dobbs, a Guided Care nurse.

On Karen’s initial home visit, she discovered Mrs. Johnson having difficulty remembering if and when she had taken her 12 prescribed medications. Always independent, Mrs. Johnson had refused any help from her husband. After Karen introduced a pill box organizer and discussed goals of care, they reached a compromise in which Mr. Johnson was responsible for filling the pill container and Mrs. Johnson took the pills out of the container and self-medicated. Karen contacted the cardiologist and discovered several missed appointments due to the travel distance. After Karen’s discussion with the primary care physician, the cardiologist, and the Johnsons, they all agreed the coumadin levels would be drawn at a local laboratory and the results sent to the cardiologist for monitoring. Karen enrolled Mr. and Mrs. Johnson in a chronic disease self-management course, in which they learned how to set goals and create realistic actions to reach their goals. The coumadin had increased Mrs. Johnson’s fear of falling and resulted in reduced mobility and altered gait. Mrs. Johnson chose to focus on improving her health through exercise, and she set goals that she now reviews with Karen during monthly coaching calls. Mrs. Johnson has been able to keep her coumadin levels in check with no repeat hospitalization, and she reports enjoying short walks with her husband – something they enjoyed in the past but had given up because of her fear of falling.

Case #2

Mrs. Virginia Adams is an 87-year-old widow with congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and diabetes. A patient of Dr. Davidson’s for over 16 years, she has steadily declined to the point where she fell recently and bruised her hip while carrying groceries into her home. Meeting the criteria for Guided Care, she received a letter explaining the program and agreed to participate.

Guided Care Nurse Julie Barnes met Mrs. Adams in her home for the initial home visit. The 1890s row house located in Washington, D.C. has street parking and six steps up to enter the two-story home. Mrs. Adams lives alone and she has a daughter in a neighboring city who works full-time and is only available to assist her on the weekends. As Julie completed her initial home assessment, she noted a broken glucometer, smoke detectors that needed batteries, no hand-held shower or grab bars in the bathroom, and carpet spill stains throughout the house. As Julie finalized the Care Guide with Mrs. Adams and Dr. Davidson, they agreed on priorities of obtaining a working glucometer and enrolling in a fall prevention class.

After six months of enrollment in Guided Care, Julie received a phone call from Mrs. Adams who reported swollen legs, shortness of breath, and wheezing. After instructing Mrs. Adams to go immediately to the hospital, Julie met her in the emergency room and provided the emergency physician a copy of the Care Guide, including the results of her most recent echocardiogram. Mrs. Adams was admitted to the hospital, treated for pneumonia, and sent home with a follow-up appointment scheduled for the next day. Unfortunately, on her way to the appointment, she was in a car accident which resulted in hospitalization. In her weakened condition, Mrs. Adams would not be able to return home to recuperate. Julie reached out to her daughter, who agreed to be the primary caregiver and take her mother home when discharged. On Julie’s home visit two days post-discharge, she found the daughter overwhelmed with the new responsibility of caring for her mother. The immediate concern was Mrs. Adams wandering the house at night and sleeping during the day. A change in medication by Dr. Davidson along with a pill box organizer provided by Julie helped to stabilize Mrs. Adams’ sleeping patterns, reducing her daughter’s anxiety and sleep deprivation. In addition, Julie enrolled the daughter in a caregiver support group offered by the community. Mrs. Adams has been able to maintain herself at her daughter’s home with the help of her daughter, the GCN, paid aides, and home safety equipment.

Lessons learned

We learned several lessons in six years of testing Guided Care in community primary care practices. Our multi-site randomized trial showed that, compared to usual care, Guided Care improves patients’ rating of the quality of their care (Boult et al. 2008; Boyd et al. 2010), reduces family caregivers’ strain (Wolff et al. 2009; Wolff et al. 2010), improves physicians’ satisfaction with chronic care (Boult et al. 2008; Marsteller et al. 2010), and suggests that Guided Care reduces the use and cost of expensive services (Leff et al. 2009).

We also learned that: 1) most patients and their families love Guided Care, saying that Guided Care is “like having a nurse in the family;” 2) it is important to thoroughly orient the primary care physicians and their office staffs to the goals and processes of Guided Care; 3) it is also important to thoroughly integrate the GCN into the many processes of the practice; 4) focused teamwork by the primary care physician and the GCN would be facilitated if each received tangible rewards for attaining the goals of Guided Care.

Practices that are interested in adopting Guided Care need to determine whether they can meet six requirements:

1. Sufficient number of patients with complex conditions: the practice must have a large enough panel of patients so that it includes enough chronically ill patients to constitute a caseload of 50 to 60 patients for the GCN. A practice with at least 300 Medicare patients is usually sufficient. Practices with higher numbers of chronically ill patients may be able to support more than one GCN. Practices with fewer chronically ill patients could share a GCN if they were in close proximity to each other.

2. Office space: a small, private, centrally located office for the GCN. An ideal location is near the physicians’ offices with convenient access to the practice’s staff, medical records, supplies, and office equipment.

3. Health information technology: the practice must have a system that supports Guided Care by generating and updating evidence-based Care Guides, checking for drug interactions, providing reminders, and documenting contacts.

4. Commitment: the practice’s physicians and office staff members need to work collaboratively with the GCN. Integration of a new type of health care provider into a primary care practice is a process that requires careful planning, optimism, open communication, honest feedback, flexibility, perseverance, and patience.

5. Supplemental revenue: Guided Care generates additional costs for the practice: the GCN’s salary and benefits, office space, equipment (computer, cell phone), communication services (cell phone service, access to the Internet), and travel costs. To adopt Guided Care, a practice must receive a supplemental stream of revenue to offset these costs, for example, capitated monthly “care management” payments for providing in “medical home” services or for participating in Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs).

6. Patients and families must agree to develop and maintain a partnership with their GCN.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree