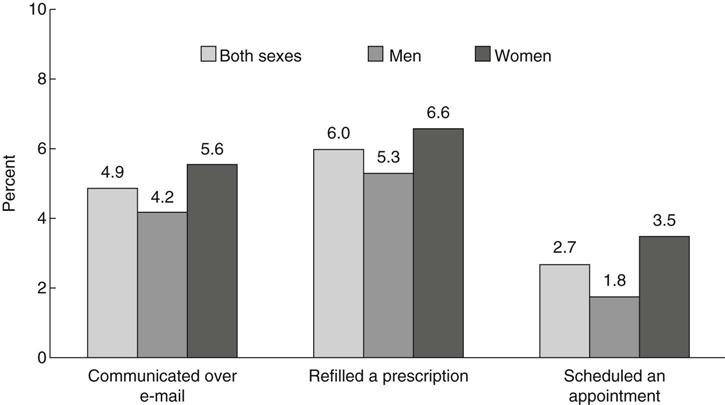

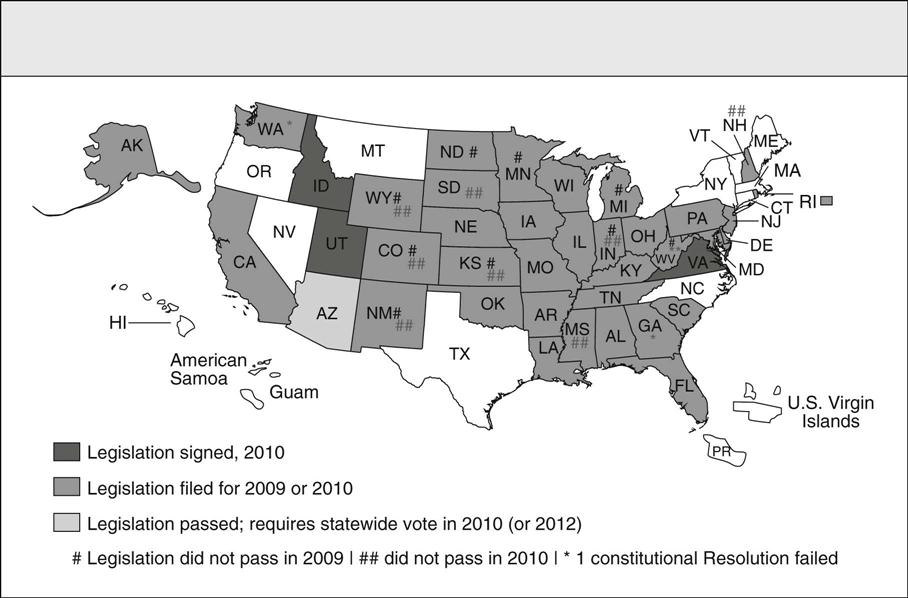

Deborah B. Gardner and Amanda L. Ebner “The bill I’m signing will set in motion reforms that generations of Americans have fought for and marched for and hungered to see.” —President Barack Obama, New York Times, March 23, 2010, before signing the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act On March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law H.R. 3590, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148), and 7 days later he signed H.R. 4872, the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-152). This contentious yet long awaited legislation will fundamentally change the United States health care system. The reconciliation bill combined with the Senate-passed bill affects American health care in five notable ways. First, the Act expands health care access for more Americans by preventing insurance companies from discrimination based on preexisting conditions (starting in 2014). Second, the bill also expands access by providing subsidies for American families earning up to $88,000 annually (for a family of four). Several non-profit advocacy organizations, including the Patient Advocate Foundation and Coverage for All, are already assisting families in securing coverage and prescription subsidies prior to the full reinstatement of the Act in 2014. Third, the Act extends prior policies, as dependent children will now remain insured under their parents’ coverage until age 26. Next, access is increased as employers with more than 50 employees will be required to cover health care costs with steep per-employee fines for violations. Finally, the passage of the reconciliation bill adds new approaches with free preventive screenings to seniors on Medicare and closes the so-called “doughnut hole” in Part D prescription drug coverage by 2011. The combined legislation will extend coverage to an estimated 30 million uninsured Americans. This legislation will require most Americans to have health insurance coverage and adds 16 million people to the Medicaid rolls. The law will cost the government about $938 billion over 10 years, according to the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, which has also estimated that it will reduce the federal deficit by $143 billion over a decade (Box 63-1). Indeed, the sheer scope and complexity of the nation’s health care system as part of a larger political and global economic context make the implementation of this new health care legislation a most formidable endeavor. The 2076-page Affordable Care Act symbolizes the complexity of this reform effort. Claims that health reform will fail continued as threats of repeal were voiced by Republican challengers even while President Obama was signing both Acts into law. And the public has heard these attacks on the reform loud and clear. According to a Gallup poll on health care reform taken a week after Obama signed the law, a solid majority of Americans think it will make both budget deficit and health care costs worse (Newport, 2010). Since key provisions don’t begin until 2014, both skeptics and supporters will have plenty of time to assess the law, its prospects for success, and, of course, its forecasted cost. This chapter focuses on the landmark legislation enacted by the 111th U.S. Congress to remedy this nation’s broken health care system and the challenges reformers will face in implementing these policies. The history and current context that underscore this legislation will be described. The health care climate and institutional politics at the national and state levels of government are examined. The critical need to control health care costs, connect prevention with quality care and patient safety, integrate technology for improving health care coordination, contain the threat of bioterrorism, and combat the growing obesity epidemic will be explored. These are tangible examples of issues that must be addressed in the redesign of a sustainable health care system that provides access to quality outcomes for all U.S. citizens regardless of income, race, or geographic location. Health care reform has been a holy grail of Democratic presidents. Truman, Johnson, Carter, and Clinton all set out to find consensus to provide every American with health insurance coverage, only to end up empty-handed. President Franklin D. Roosevelt hoped to include some kind of national health insurance program in Social Security in 1935. President Harry S. Truman proposed a national health care program with a multi-payer insurance fund. Since then, every Democratic president and several Republican presidents have wanted to provide affordable coverage to more Americans. President Bill Clinton offered the most ambitious proposal in 1993-1994 and suffered the most spectacular failure (Stolberg & Pear, 2010). Despite these daunting precedents, the election of President Barack Obama was seen by most Democrats as a public mandate on health care reform. Its passage assures Obama a place in history as the American president who finally succeeded where others tried mightily and failed. One of the most significant differences between the Clinton reform efforts and those of 2009-2010 is that employers and corporations, alarmed at the soaring cost of health care, agreed that changes were necessary. Some of the same insurance companies, which helped defeat the Clinton plan, began 2009 by claiming that they accepted the need for change and wanted a seat at the negotiating table. As the bills developed, however, these powerful stakeholders became strong opponents of some Democratic proposals, especially one known as the “Public Option” to create a government-run insurance plan as an alternative to their offerings. To give a sense of the contextual obstacles impeding the legislation’s passage, the scale and quantity of problems confronting the country and President Franklin Roosevelt at the start of the Great Depression in 1929 are repeatedly evoked as the most comparable historic referent (Baker, 2009). “The Great Recession,” prompted by overspeculation in finance and brought to light with the housing market collapse, demanded immediate and deliberate actions of risky unprecedented proportions early in the Obama presidency. Immediately after the president’s election, critics argued that pressing priorities such as the U.S. economy, energy independence, global warming, and the Middle East needed attention more than health care reform. In addition to being confronted with major foreign policy decisions regarding the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, on the domestic front, the administration’s early months in office were indeed dominated by a single issue: the economy. In fact, the economy’s relentless slide in late 2008 began reshaping the Obama team’s agenda-setting. As president-elect, he was forced to contend with whether or not to bail out the financial system, and how to keep General Motors and Chrysler from going under (Stolberg & Pear, 2010). Because health care in this country is the most expensive in the world but not the strongest in health outcomes, 1 of every 6 dollars earned is spent on health care, and the current system has forced more than 1 million people into bankruptcy, the Obama administration argued that the biggest threat to the nation’s economic balance sheet was the skyrocketing cost of health care (Gawande, 2009). To extend medical coverage to everyone was also a way to bring costs into control, thus health care reform was presented as an integral issue to economic stability. President Obama’s first major initiative incorporated the two inseparable issues in a stimulus package to pump money into a downward-spiraling economy. In February 2009, only 3 weeks after his inauguration, Congress passed the massive $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in an effort to create jobs, stimulate economic activity, and increase transparency in government spending. Republicans derided the bill as unaffordable and excessive. Not a single Republican in the House voted for the package, and only three Republican senators did, narrowly avoiding a filibuster. Under the aegis of economic recovery, the Act set aside more that $100 billion, enabling extensive provisions to address both immediate and long-term deficiencies in the health care infrastructure. For example, it helped an estimated 7 million unemployed Americans retain their health care coverage under COBRA and roughly 20 million Americans keep their Medicare coverage despite state budget shortfalls; allocated $1 billion toward prevention and wellness programming; and invested an immediate $24 billion for computerizing medical records to reduce costs and ensure patient privacy in records exchange (www.Recovery.gov, 2010). Furthermore, the Act provides funding for comparative effectiveness research, funds for the next generation of medical professionals, and invests in community health centers and health care technology for at-risk communities. Several states have already begun implementing strategies that mirror national health priorities, however, many of the states’ reactions to federal reform have been neither uniform nor without contention. Despite the president’s signature, the legislative work on the bill is not complete at the time of this writing, nor is the partisan clash over it. States have an extensive and complicated shared power relationship with the federal government in regulating various aspects of the health insurance market and in enacting health reforms. In general, the health insurance reform measures, covering both 2009 and 2010, seek to make or keep health insurance optional, and allow people to purchase any type of coverage they may choose. However, in response to federal health reform legislation, members of 39 state legislatures have proposed legislation to limit, alter, or oppose selected state or federal actions, primarily targeted at single-payer provisions and mandates that require purchase of insurance (Figure 63-1) (Cauchi, 2010). Simply put, the individual mandate, passed by both chambers, requires people to buy health insurance or pay a financial penalty. Republicans argue that this is the government forcing people to buy a particular product. Democrats contend that the current system is forcing citizens out of health insurance or into few and expensive coverage options. Overall, Democrats designed this mandate to make reform more cost-effective by creating larger population pools that pay into the care of all risk levels. It is likely that the contours of this provision will be contentious and hotly debated in the judicial arena. Liberals argue that they have seriously reviewed the legalities of this mandate, and that the penalty is constitutional. Conservatives are advancing other constitutional arguments against reform plans including the regulation of insurance companies as the illegal seizure of private property. The pivotal argument here is that state law cannot nullify federal law. One strong source of congressional power is the General Welfare Clause, which provides the legislature with power to provide for the common defense and general welfare of the U.S. Jack Balkin, a constitutional law professor at Yale who wrote about the constitutionality of the individual mandate, argues that by insuring more people and preventing insurers from denying coverage because of preexisting conditions, the health reform bill serves the “general welfare” (Jost, 2010). While politicians and legal experts have expressed widely varying pro and con opinions on the validity of the approach, most experts see the purpose of these efforts as symbolic rather than legal, intended to send a message of political protest. Significantly, some analysts predict that partisan politics will delay and complicate implementation of health reform, as these legal collisions will be used as rallying points to influence the 2010 congressional elections (Fletcher, 2010). In addition to the difficulty of dealing with a broken health care system, the months leading up to the health care reform vote revealed the legislative processes taking place in Congress to be in need of its own reform. While some argue that the fact that health reform legislation was passed refutes such a position, what is also apparent is that Democrats and Republicans currently vote against each other more regularly than at any time since Reconstruction. Two exemplars of legislative dysfunction during the health care debates were the misuse of the filibuster and the misrepresentation of reconciliation procedures. Conventional wisdom acknowledges that the filibuster is most commonly used to obscure change and clarity in legislative discussion, if not paralyze it altogether. According to UCLA political scientist Barbara Sinclair, about 8% of major bills faced a filibuster in the 1960s, and in this decade it has risen to 70% (Klein, 2009). The second parody of deliberative democracy was the Republican battle against the use of reconciliation in the last days of the health reform legislation process. They argued that Democrats were using a procedural gimmick to “jam” the legislation through, and Democrats retorted by listing all the major bills the Republicans had passed via reconciliation when they were in the majority (such as the Medicare drug plan and both Bush tax cuts). The absence of bipartisanship and the use of the filibuster to obstruct progress rather than protect debate, has given any Congressperson the ability to hold a bill hostage to his or her demands. Some observers go so far as to argue that the continued misuse of the filibuster threatens successful governance overall (Klein, 2009). Certainly, the ability of the public to keep check on legislative decision-making has been undermined by these uncompromising, obfuscating practices. Efforts to make the legislation process transparent and intelligible for the public backfired in the thick of a contentious partisan background. Rarely have as many statistics been summoned, disputed, recorded, and maligned as during the months it has taken to pass the health care reform bill. Health care stirs powerful emotions, and the complexity of the subject, combined with round-the-clock politicized media coverage, makes it difficult for people to balance their emotional reactions with rational ones. Political observers note that as the public witnesses partisan polarization on an issue—with Democrats on one side and Republicans on the other—it receives a cue to harden its own opinions, which in turn reinforces the hardening of partisan political positions (Klein, 2010). Political representatives used the debate over health care reform to accentuate differing ideologic approaches regarding the role of government. The role of government in this country has long been a deeply divisive issue. While across the citizenry, there is a shared belief that the role of government is to provide people the freedom necessary to pursue their own goals, in practice, outlining paths that carve a balance between individual rights and collective needs is fraught with political factionalism. Generally, conservative policies tend to emphasize the empowerment of the individual to solve problems rather than the government. In contrast, liberals see government action as necessary to achieve equal opportunity and tend to emphasize the role of the State in enacting and enforcing policies that empower individuals. Placing the role of the government somewhere in the middle, which is how the Obama administration describes its health care legislation, seemed to displease both liberals and conservatives. Amidst this ongoing context of zero-sum politicking in Congress, it is not surprising that while Americans vastly support the individual components of health reform they remain skeptical when asked about the hazy concept of “comprehensive reform.” During the congressional recess in August 2009, a wave of conservative protests almost ensured the death of health care reform. Opposition to the president’s health care plans were likened on talk radio to something out of Hitler’s Germany, lampooned by protesters at congressional town-hall-style meetings and vilified in television commercials (Begley, 2009). In response, President Obama confronted a critical Congress and a skeptical nation, decrying the “scare tactics” of his opponents and presenting a forceful case for a sweeping health care overhaul that had eluded Washington for generations. An instance of political machinations stifling discourse occurred during this same presentation when President Obama refuted claims that Democrats were proposing to provide health coverage to illegal immigrants, and Representative Joe Wilson of South Carolina yelled, “You lie!” Mr. Wilson apologized, but his outburst led to a 6-day national debate on civility and decorum, and the House formally rebuked him a week later. Not surprisingly, proponents of health care reform were shocked at the disparagement of the bill; however, its passage proved inevitable as the U.S. joins other nations in designing a more inclusive, universal model of health care. The final health care bill targets three key operational sectors of health care: (1) insurance practice, (2) employer-based coverage mandates, and (3) subsidies for vulnerable populations. First-stage implementation of the new health care legislation began with the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) providing guidance through rule. Immediately after health reform was signed, HHS Secretary Kathleen Sebelius (USDHHS, 2010b) sent a letter to America’s Health Insurance Plans (the trade association representing the plans) emphasizing the importance of compliance with the more immediately effective provisions in the health reform bill, specifically the “pre-existing condition exclusion.” She made it clear that rules to be established reinforce compliance with the requirements to ensure that children not be denied access to their parents’ health insurance or denied treatment due to a preexisting condition. To address the overlapping sectors of insurance practice and vulnerable populations, HHS has begun coordinating rapid implementation with state and insurance providers. Additional letters from Sebelius in April 2010 attempted to gather information on the number of states who would be interested in participating in the temporary high-risk pool program established by the new health insurance reform law (USDHHS, 2010b). States were given the option to provide coverage to the uninsured with preexisting conditions. The federal government will likely also offer a national pool. State-supported risk pools will phase out in 2014 when private insurance companies will be forced to sell policies to the “medically uninsurable” (Varney, 2010). Currently, the high-risk pools in most states are largely viewed as a failure. Premiums and deductibles are wildly expensive, and the policies have spending caps that are frequently exceeded. For example, the California plan is capped at 7100 members and often has a waiting list. The new federal health care law sets aside $5 billion to fund new high-risk programs that are more affordable and open to more people. Deborah Chollet, a health insurance expert at the nonpartisan research firm Mathematica, says people who apply to the new programs will pay a standard rate, or the rate they would pay for a policy if they did not have a preexisting condition that previously excluded them from coverage (Varney, 2010). Although extending coverage to the previously uninsurable is perhaps the best-known section of the new health care legislation, significant changes are under way for conventional employer-based insurance programs as well. The U.S. faces steep health care challenges as the “baby boom” generation enters retirement and as health care reform increases demand for services. America’s health care professionals directly influence the cost and quality of health care through their diagnoses, orders, prescriptions, and treatments. Analysts are projecting a nationwide shortage of as many as 100,000 to 200,000 physicians and 250,000 public health professionals by 2020 (Dill & Salsberg, 2008), and 260,000 nurses by 2025 (Buerhaus, 2009a). Rural Americans and those living in other underserved areas across the country are especially vulnerable to health workforce shortages. While the nursing shortage has been long-standing, Buerhaus (2009b) notes that although it is temporary, the recession has eased the shortage of hospital nurses, but large shortages are still expected in the next decade. The initial findings from the 2008 HRSA (USDHHS, 2010a) national survey of registered nurses released in 2010 also reports that the number of licensed registered nurses in the U.S. increased to a new high of 3.1 million between 2004 and 2008 reflecting a 5% increase. The ability to meet the country’s demand for nurses remains a daunting goal. Over the past decade, numerous initiatives to recruit more nurses into the profession have been launched, and many are successful. While interest today in a nursing career is growing, with almost 50,000 qualified applicants turned away in 2008, this increase in demand reveals the complex problem of a low supply of nursing faculty as a primary barrier in the education pipeline for preparing the numbers and types of nurses so badly needed (AACN, 2009). As policy efforts are developed to assure an adequate health care workforce, the question is whether the problem is a shortage of health professionals overall, or is it only with the distribution of certain types of health professionals in certain areas of need? The answer is both. Assessing, projecting, and planning health workforce needs is complicated, and no single entity in the U.S. is in charge of workforce planning (Derksen & Whelan, 2009). The absence of a cohesive approach to workforce shortages, training of health professionals across disciplines, and distribution of health professionals to areas of need must be addressed if health care reform policy is to be successfully implemented. The federal government pays for health care workforce development through funding of two broad training categories. The first and largest payment comes from Medicare and Medicaid, which provide support for Graduate Medical Education (GME) by subsidizing hospital training through add-on payments. Teaching hospitals are reimbursed to train physicians in residency programs and for hospital-based nursing diploma education. Today with only 7% of nurses receiving their education in a hospital-based setting, nurses receive little benefit from this funding stream. Combining the last data available from 2007, approximately $12 billion was provided in GME subsidies (Derksen & Whelan, 2009). Medicare still pays about $150 million per year to these hospitals for nurses’ training (Livsey, 2007). The second and more modest funding component is provided through Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services that administers health workforce programs. With a 2010 budget of $7.2 billion, HRSA programs train health care professionals and place them where they are most needed. Grants support scholarship and loan repayment programs at colleges and universities to meet critical workforce shortages and promote diversity within the health professions. Congress and the Obama administration began addressing workforce shortage issues by allocating $500 million to workforce development from the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). $200 million went to programs authorized by Titles VII (Health Professions) and VIII (Nurse Training) of the Public Health Service Act to expand training and educational opportunities. These sections of the Act include primary care medicine and dentistry programs, public health and preventive medicine programs, and scholarship and loan repayment programs. Of the $80 million awarded to date, about half has gone to students, health professionals, and faculty from minority and disadvantaged backgrounds. The other $300 million is being used to increase the capacity of the National Health Service Corps (NHSC). The NHSC, which is authorized through PHSA Title III, provides scholarships and loan repayment to health professionals who agree to work in areas with too few health professionals. It is worth noting that historically, for every federal dollar spent on HRSA’s primary care, nursing, and dental workforce programs, teaching hospitals were paid $24 by Medicare and Medicaid to subsidize physician training. This reflects the severe funding inequities, as physician education and hospitals are strongly supported with GME funds, and nursing and other health professionals are minimally funded by comparison through HRSA dollars. The final Health Care Reform legislation includes important changes to this chronic issue as graduate nurse education and postgraduate experience demonstrations will be funded through Medicare funds (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L.111-148) provides long-term strategies for improving health care workforce shortages. The first broad strategy authorizes the establishment of a multi-stakeholder Workforce Advisory Committee to develop a national workforce strategy. The second strategy entails an expansion of Medicaid to fiscally pay for health promotion and disease prevention as well as increases in Medicare payments for primary care physicians. Likewise, the laws and regulations that govern GME funding will expand from the strict hospital-based setting to the use of outpatient settings for residency training, and it will give priority to states with the largest rural and underserved areas as well as to primary care and surgery providers. Teaching Health Centers will be established that will be eligible for Medicare payments for operating primary care residency programs in 2010. Another health reform workforce initiative includes support for the development of training programs that focus on primary care models such as medical homes, team management of chronic diseases, and those that integrate physical and mental health services. This initiative has a 5-year authorization. A complementary initiative provides training to family nurse practitioners who provide primary care in federally qualified health centers and nurse-managed clinics, again a 5-year authorization. Not only are these initiatives authorized for longer periods of time providing stronger program evaluation, they represent a realignment of federal incentives for improving our nation’s health workforce capacity and quality. As the federal government has been looking at health reform from a national perspective, states have been struggling with the same issues locally. The number of uninsured people varies considerably from state to state, ranging from 2.7% of the population in Massachusetts, according to state government data, to 25.2% in Texas, according to a 2008 Kaiser report on state health facts. The number of uninsured increased during the recession as people lost jobs and employer-sponsored health insurance. Concerned about the problem of limited health insurance, states have taken a number of steps to expand access to coverage, including expanding public programs like Medicaid and CHIP, to cover additional children and adults. States’ fiscal concerns have slowed down their efforts to provide access to health insurance for the uninsured. In 2008, nearly half the states faced budget gaps, and by 2009 the number rose to two-thirds. The state budget situation is grim and getting worse with each new revenue revision. As of December 2008, at least 10 states have imposed and another 10 are considering across-the-board budget cuts. Six states (Maryland, New Hampshire, New York, South Carolina, Utah, and Vermont) have been forced to cut their Medicaid budgets. Currently, 30 states have proposed health care reform legislation they will consider alongside the federal reform legislation (National Conference of State Legislatures [NCSL], 2010a, 2010b). The Commonwealth Fund Commission’s report, the 2009 State Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance (2009), examines trends on state’s progress toward achieving systems and models of health care that meet their residents’ needs. This report examines how states compare on 38 key indicators of health care access, quality, costs, and health outcomes. The findings of the report conclude that these indicators vary significantly depending on the state you live in. The scorecard findings reflect deteriorating coverage for adults and rising costs with broad geographic disparities and strong evidence of poorly coordinated care. In 2009, Vermont, Hawaii, Iowa, Minnesota, Maine, and New Hampshire lead the nation as the top-ranked states in terms of performance. Patterns indicate that when public policies and state and local health care systems are aligned, individual states have the capacity to do much better. Vermont, Maine, and Massachusetts have enacted comprehensive reforms to expand coverage and put in place initiatives to improve population health and benchmark providers on quality. Minnesota is a leader in bringing public and private-sector stakeholders together in collaborative initiatives to improve the overall value of health care. Unfortunately, even these leading states face the problem of escalating health care costs (The Commonwealth Fund, 2009). While other viable models are emerging at the state level, early attempts from Massachusetts and Vermont have received national attention and demonstrate the promise of innovative state reform efforts that are attempting to improve access while actively evaluating cost-effectiveness and quality changes. The U.S. continues to spend more on health care than any other nation, yet numerous studies have found that there is no relationship between spending and the quality of care. The Institute of Medicine’s Quality Initiative, launched in 1996, was a tipping point in collective learning about and acknowledging how poor the U.S. Health Care system was actually functioning. Documentation of the serious nature and high costs of hospital errors on human health and safety became a foundation for clinical practice reform (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Dougherty and Conway (2008) advocate a three-prong approach to transforming the quality of U.S. health care: translate scientific research into clinical practice, develop patient-specific evidence for effectiveness (“the right treatment for the right patient in the right way at the right time”), and make the policy changes necessary to improve population health (p. 2319). While the value of decreasing error in caring for patients is supported by all health care professionals, the hidden and hierarchical culture in health care was one of fear, and to report error was to risk public “shame and blame.” One legislative response to this critical issue in American health care was the passage of the 2005 Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act. The Act established increased protection for reporting medical errors. As this culture shift supports the value for acknowledging errors and “near misses,” and tools are developed to guide learning, a foundation is laid for a healthy inquiry into examining all clinical practice from a safety and quality point of view. Indeed, a paradigm shift from fear to accountability for medical professionals has certainly become a more consistent reality (Wachter & Pronovost, 2009). Health care quality has made significant headway as evidence-based practice has become an accepted standard for health care delivery and multiple institutions across the country guide the development for continual improvement. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) a two-decade–old agency within HHS, was among the first to emphasize evidence-based practice. The AHRQ now provides 17 toolkits for multidisciplinary clinical professionals to address patient safety at the point of care in hospitals and outpatient settings, during consumer self-care, and for informal caregivers. In terms of federal priorities in quality care, the Recovery and Reinvestment Act allocated $1.1 billion for comparative effectiveness research (CER), systematic research that compares different interventions and strategies to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor health conditions. Clinical effectiveness research is defined as a rigorous evaluation of the impact of different options that are available for treating a given medical condition for a particular set of patients. Such options are commonly drugs and surgery. Interest in CER has been spurred by ever-rising health care costs and the persistent nagging evidence of unexplained variations in clinical practice, which was first identified across large geographic regions in the Dartmouth Health Care Atlas and is now increasingly recognized in units as small as individual practices. However, there is controversy. Although some health professionals see such research as desired and even necessary given the current economic crisis and rise in health care spending, others fear a slippery slope leading to inflexible coverage decisions and even explicit rationing (Pentecost, 2009). This tension reflects the ongoing ambivalence regarding the changes that will be brought about through health care reform. While health care technology has had a pronounced effect on the growth in health spending, it has also yielded major improvements in quality and cost-effectiveness. Health care reform legislation will invest $24 billion for computerizing medical records. Audiovisual telemedicine using video-chat technology, which in recent years has replaced telephone-only formats, has already been credited with increased stroke evaluations in rural households; those using the technology report a 96% accuracy rate in diagnosis and treatment (Mayo Clinic, 2010). The benefits to making medical information electronic lie not only in improved treatment options but also in more immediate and convenient communication between clinicians, lowered costs of transferring and maintaining records, and minimized communication errors (Adams, 2010). The cost-reductive impact of telemedicine is felt across all major sectors of current health care spending and is particularly well-positioned to reduce expenditures in hospital and home care, which combined, represent 41 cents of every health care dollar (Hartman, Martin, McDonnell, Catlin; National Health Expenditure Accounts Team, 2009). Older health care professionals, like many older Americans, are often slow or late adopters in the use of technology. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) provisions within the Recovery Act of 2009 include physician penalties for non-adoption (lowered Medicare payments by 2015), yet economists estimate that the financial incentives offered to physicians in the $28 billion stimulus will far outweigh any potential non-compliance fees (Adams, 2010). One continuing concern plaguing the speedy adoption of new health care technologies is privacy. However, ample privacy protections were written heavily into the 2008 medical records bill (H.R. 6357), which required the HHS Secretary to author an informed-consent agreement for all Americans whose data will eventually be digitalized (Armstrong & Nylen, 2008). Miller and Tucker (2009) found that in states where privacy regulations are at odds with the new federal medical records guidelines, aggregate electronic medical record (EMR) adoption by hospitals is reduced by 24%, a critically discouraging number given the minimal nationwide 25% EMR adoption goal of H.R. 6357. There are working models available to suggest the efficacy of an EMR/EHR program. Kaiser Permanente already has a linked electronic network of over 14,000 physicians that can access and share records, citing their “better management” practices as the basis for their claim that Kaiser patients have a 30% lower chance of dying from heart failure than members of the general population (Carey, 2008). Furthermore, the NIH Public Access Policy (revised in 2009), stating that the public has online open access to the results of all NIH-funded research via PubMed Central (PMC), sets a precedent for electronic and transparent transmission of health information that may loosen the tight grip of secrecy surrounding the availability, authority, and accessibility of health information in the U.S. However, processes of communication, publication, and dissemination must continually be revisited to ensure that cutting-edge research and relevant results are reaching the at-risk populations most in need of clinical guidance. The battle between paper-based and electronic medical records may not be one of consent or even of funding, but rather one between the status quo and uncertainties of overhauling an institutionally entrenched records system. Recent information from the CDC suggests an increase in consumer use of the Internet to access health information and contact health care providers, signaling a potential change in the norms of information access and distribution across the health care system (Figures 63-2 and 63-3).

Contemporary Issues in Government

Historical Perspective

The Rocky Road to Health Insurance Reform: States Rebel

Congressional Reform

The Battle over Public Opinion

Federal Implementation of Health Insurance Reform

Health care Workforce Shortages and Reform Resolutions

State-Level Health Reform

Health Care Quality and Patient Safety

Medical Technologies

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access