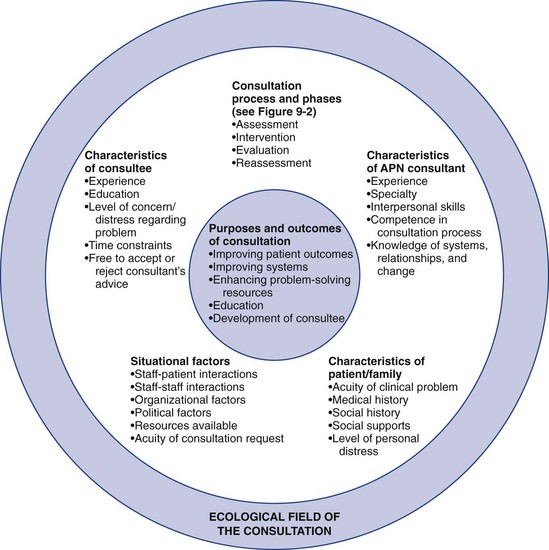

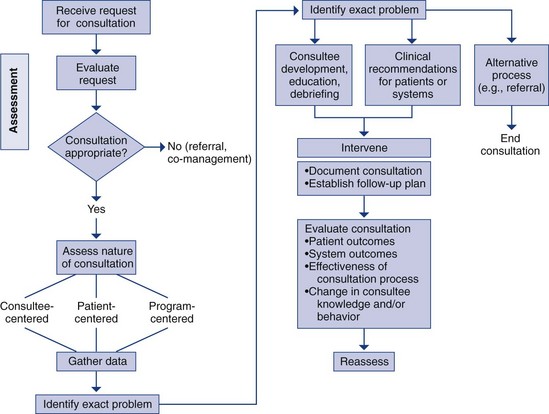

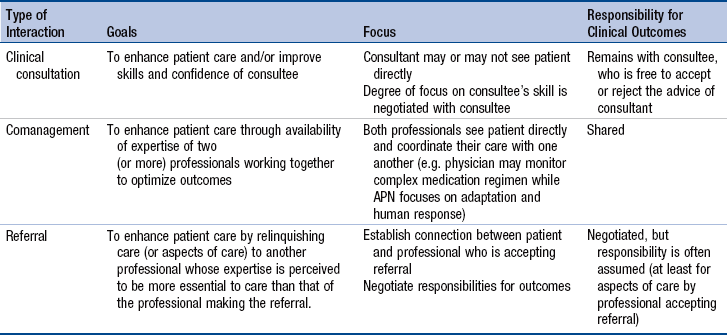

Chapter 9 Consultation and Advanced Practice Nursing Model of Advanced Practice Nursing Consultation Common Advanced Practice Nurse Consultation Situations Advanced Practice Nurse Consultation in Practice Advanced Practice Nurse–Physician Consultation Advanced Practice Nurse–Staff Nurse Consultation Mechanisms to Facilitate Consultation Issues in Advanced Practice Nurse Consultation Developing Consultation Skills in Advanced Practice Nurse Students Using Technology to Provide Consultation Documentation and Legal Considerations Discontinuing the Consultation Process Developing the Practice of Other Nurses Consultation Practice Over Time Evaluation of the Consultation Competency Consultation is an important aspect of advanced practice nursing. As advanced practice nursing has evolved over the years, the consultation competency has received increased attention and is now explicitly addressed as a role expectation. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2006, 2011) has highlighted consultation as an essential component of master’s and Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) programs. In defining the essentials of DNP education, the AACN emphasizes the need for exquisite skills in the areas of collaboration and consultation for DNP-prepared advanced practice nurses (APNs). Collaboration is considered in depth in Chapter 12. The complexities of today’s health care settings require that all APNs offer and receive consultation and understand, clinically and legally, the differences between consultation and collaboration. This chapter will address APN consultation in the following manner: • Establishing consultation as an essential component in APN practice • Defining consultation and distinguishing it from other APN relationships/responsibilities • Describing consultation in the context of specific APN roles • Reviewing a model of consultation developed by Barron and White (2009) • Highlighting the importance of consultation in education • Evaluating the consultation process The enduring works of Caplan (1970), Caplan and Caplan (1993), and Lipowski (1974, 1981, 1983) continue to inform our thinking, writing, and practice in the area of consultation. A number of the sources used to prepare this chapter are considered classics or have ongoing relevance, despite their early publication dates. APN consultation requires the building of relationships with health care professionals within nursing and across disciplines; in advanced practice consultation, the APN offers his or her expertise with colleagues to optimize patient care. Barron and White (2009) have made the important point that consultation may be a significant variable that can contribute to the effectiveness of APNs. Opportunities to consult present themselves to APNs on a daily basis. In clinical practice, the APN applies expertise to the clinical situation and consults with other professionals across disciplines—with an APN colleague regarding a difficult clinical problem, with a physician colleague about how to address a specific patient management issue, or with the nursing staff about how to manage a patient’s symptoms or how to follow the clinical guidelines required to handle a unique clinical problem (e.g., infectious disease precautions). In the context of consultation across disciplines, the APN has a unique understanding of the clinical situation from a nursing perspective and is therefore viewed as an expert. Even in a situation in which the APN is working with someone with more experience, such as a specialist physician who is also involved in the patient’s care, the unique nursing perspective and expertise of the APN can be brought to bear in the discussion, and it is requisite for the APN to offer these specific insights. This supports Barron and White’s (2009) position that the ability of the APN to consult effectively directly influences his/her performance and success in the role. It is important to mention that there are still some state laws and regulations that mandate a consulting or collaborating physician for advanced practice nurses and for prescriptive privileging. The wording of these mandates often directly states or implies a hierarchical relationship between the APN and physician, which is contrary to the description of consultation being put forth here. As far back as 1999, Minarik and Price described the critical importance of conceptual clarity for legislative and regulatory reform and its far-reaching impact on APN practice. At the state and federal levels, medical societies have attempted to limit advanced practice nursing, so the terminology included in the legislation describing the relationship between physicians and APNs is of enormous significance with regard to collaboration and consultation. Minarik and Price (1999) made the compelling argument that the practical effect of the language of legislation related to the financing of health care can be devastating to advanced practice nursing, even though state boards of nursing are clear in their regulations about the appropriateness of the expanded scope of practice for APNs (LeBuhn & Swankia, 2010). The Future of Nursing report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2011) highlights the ever-increasing need for all nurses, including APNs, to be able to function at the full capacity of their education to meet the increasing needs of patients. APNs must be sophisticated readers of legislative proposals that include mandated relationships between physicians and APNs. Because legislation is drafted regarding scope of practice and direct reimbursement for practice, APNs need to be clear and articulate about the implications of such terms as collaboration, supervision, direction, and consultation. Medical societies may propose such terminology with a clear intent to mandate hierarchical relationships with physicians to limit advanced practice nursing. Because mandated relationships between APNs and physicians may constrain advanced practice nursing consultation, APNs should be aware of the statutes and norms that regulate their practices. The goals and outcomes of consultation are relevant to ongoing efforts to reform health care. APNs can help bring about the national goal of high-quality, cost-effective health care for every American, as outlined in the IOM report (IOM, 2011). Through consultation, APNs create networks with other APNs, physicians, and colleagues, offering and receiving advice and information that can improve patient care and their own clinical knowledge and skills. Interacting with colleagues in other disciplines can enhance interdisciplinary collaboration and subsequently enhance patient outcomes (see Chapter 12). Consultation can also help shape and develop the practices of consultees and protégés, thereby indirectly but significantly improving the quality, depth, and comprehensiveness of care available to patients and families. Consultation offers APNs the opportunity to influence health care outcomes positively, beyond the direct patient care encounter. The term consultation is used in many ways. It is sometimes used to describe direct care—the practitioner is in consultation with the patient. It may be used interchangeably with the terms referral and collaboration. Thus, how the term is being used in a given situation may be unclear, and it may be difficult to determine exactly what is being requested and what is expected. A lack of clarity about the specific process being used for clinical problem solving leads to confusion about roles and clinical accountability. The more precisely the word consultation is defined, the more likely consultation will be used for its intended purposes of enhancing patient care and promoting positive professional relationships that result in true collaboration and optimal patient outcomes. Because consultation is a core competency of advanced practice nursing, this precision is needed for communication within and outside the profession. It is extremely important to understand the differences between consultation and other types of professional interactions. Table 9-1 summarizes these differences, which are further described in the remainder of this section. Clarifying Definitions of Clinical Consultation, Comanagement, and Referral Adapted from Barron, A. M., & White, P. (2009). Consultation. In A. B. Hamric, J. A. Spross, & C. M. Hanson (Eds.), Advanced practice nursing: An integrative approach (3rd ed., pp. 191–216). Philadelphia: WB Saunders. Consultation is an interaction between two professionals in which the consultant is recognized as having specialized expertise (Caplan, 1970; Caplan & Caplan, 1993). The consultee requests the assistance of that expert in handling a problem that he or she recognizes as falling within the expertise of the consultant. Consultation is a role function used by APNs to offer clinical expertise to other colleagues, as a specialty consultant, or to seek additional information to enhance their own practice. Given APNs’ advanced knowledge and assessment skills, and in some cases expansion of the APN role into areas of specialization, consultation for peer APN expertise can foster improved accessibility, consultation, and timely and potentially improved care for patients waiting to be seen for patients with unique conditions. Comanagement is the process whereby one professional manages some aspects of a patient’s care while another professional manages other aspects of the same patient’s care. Effective comanagement requires excellent communication, coordination, and collaborative skills. Professionals who work within the same interdisciplinary team often develop systems that facilitate seamless and effective comanagement. In comanagement, both providers retain responsibility for the patient’s care (Table 9-1). APNs are often confused in practice between consultation and collaboration. Chapter 12 provides a thoughtful definition of collaboration that was first offered by Hanson and Spross in 1996: “Collaboration is a dynamic, interpersonal process in which two or more individuals make a commitment to each other to interact authentically and constructively to solve problems and to learn from each other in order to accomplish identified goals, purposes, or outcomes. The individuals recognize and articulate the shared values that make this commitment possible.” Collaboration is a process that underlies the professional interactions involved in consultation, comanagement, and referral. Whatever the nature of the consulting relationship, the APN keeps the patient at the center of her or his actions; therefore, consultation requires collaboration on some level when two professionals come together to meet patient-centered goals. Recruiting other professionals for collaboration organizes support of an interdisciplinary group, thereby increasing the impact on the patient or problem through the synergy of multiple experts. An example of collaboration may involve a geriatric clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and palliative care nurse practitioner (NP) participating in a family meeting to discuss goals of care with a frail older patient and his or her family regarding end-of-life wishes, including code status and hospice. According to Caplan’s classic definition (1970), there are four different types of consultation. Client-centered case consultation is the most common type of consultation. The primary goal of this type of consultation is assisting the consultee to develop an effective plan of care for a patient who has a particularly difficult, complex, or unique problem. In client-centered case consultation, the consultant often sees the patient directly to complete an assessment of the patient and to make recommendations to the consultee for the consultee’s management of the case. This is often a one-time evaluation, although follow-up by the consultant is sometimes needed. The primary goal is to assist the consultee in helping the patient. A positive experience when handling that specific case will enhance the consultee’s ability so that future patients with similar problems can be treated more effectively. For example, the APN may consult an infectious disease APN to elicit her or his opinion on an ongoing infection in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patient. This consultation would be specific to the clinical problem at hand and result in recommendations for the consultee to manage or comanage a challenging clinical infection with the assistance of an expert infectious disease APN. The recommendations could include information such as which antibiotics are recommended to treat the infection, how to monitor response to the antibiotics, and potential adverse effects of the treatment plan. Effective consultation can foster orderly reflection and extend the frames of reference used by the consultee to solve clinical problems (Caplan & Caplan, 1993). Both client-centered and consultee-centered case consultations have been important activities in traditional CNS practice. For example, the psychiatric CNS is often consulted by the APN in the hospitalist role who has patients with advanced dementia, behavioral disorders, or long-standing psychiatric diagnoses that may need adjustment now that the patient has been hospitalized. Although the APN hospitalist is comfortable with behavioral assessment and continuity of care, he or she may not be adept at treating the changes in behavior that can occur while the patient is hospitalized. The psychiatric CNS can apply specific knowledge, along with the necessary medical treatment, to maximize patient care while she or he is hospitalized and teach the APN these diagnostic and management techniques. In the primary care setting, this type of consultation can be seen when APNs confer with their physician or APN colleagues to confirm their differential diagnoses or individualize a treatment plan. APNs may be involved in all four types of consultation at various times. This chapter specifically considers the first two types of consultation, client-centered case consultation and consultee-centered case consultation, because the focus here is the process of interacting with other professionals regarding the care of individual patients. Case consultation can bridge the gap between evidence or knowledge and practice, assisting staff in improving care for patients and families through broadening perspectives, expanding expertise, and generalizing knowledge appropriately (Lewandowski & Adamle, 2009). The consultation competency has received significant attention in the four APN roles and is explicitly addressed as a role expectation (AACN, 2006; 2011; American Association of Nurse Anesthetists [AANA], 2005; ACNM, 2011, 2012; National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS), 2004; National CNS Task Force, 2010; National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties [NONPF], 2011). Although all APNs seek and provide consultation, the literature on consultation in specific APN roles varies. Certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), for example, specifically address consultation as an expectation (ACNM, 2011). In addition, consultation has long been a specific expectation for those in CNS positions. Consultation as a competency is less frequently addressed in the certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) and NP literature, although they are likely to consult and be consulted formally and informally in practice on a regular basis. Of the four APN roles, the CNS literature contains the largest amount of information regarding consultation. As a CNS, the professional focus remains on clinical nursing, although the CNS also spends time in nursing staff education, evidence-based practice, and system change and innovation. As a clinical expert, a CNS hones consultant-consultee relationships with the nurses who provide bedside care in the acute setting (Dias, 2010). In these consultant-consultee interactions, the CNS can influence patient outcomes by modeling and leading nurses to use evidence in making clinical decisions. For example, a CNS may discuss the chemotherapy care plan or wound care protocol with the staff nurse prior to implementation to ensure that the nurse has a complete understanding of the interventions to be provided. In the CNM role, managing patient risk and responding to the patient’s best interest drives the decision to refer for an obstetric consultation (Skinner & Foureur, 2010). In New Zealand, the obstetric consultation rate is 35%. Although the consultation rate may seem high, the reasons for consultation were significantly justified and the midwives usually continued to provide some midwifery care for the patients, even when risk had been identified. The consultation with the obstetrician did not automatically result in comanagement of the pregnant patient by the physician and CNM; rather, most patients returned to the care of the midwife with the consultant’s input (Skinner & Foureur, 2010). Some examples of NPs as consultants have been described in the literature. The development of mental health NP consultant liaisons who consult on emergency department (ED) patients has been explored in Australia (Wand & Fisher, 2006; Van Der Watt, 2010). These NPs consult with ER colleagues on patients with behavioral issues who present to the ED using therapeutic techniques and medications for acute crises, and making referrals, as needed. These roles have been shown to increase collaboration and improve patient and family satisfaction and are seen as complementary to rather than a replacement for medical psychiatric care (Wand & Fisher, 2006). Other examples of NP consultation have been illustrated—NP-led rapid response teams demonstrate decreases in need for cardiopulmonary resuscitation while providing patient treatment and staff education (Benson et al., 2008), and NPs in interventional radiology provide consultation related to vascular access and diagnostic procedures (Dryer, 2006). Barron (1989) proposed a model of consultation for CNSs that was based on the nursing process and incorporated principles from the work of Caplan (1970) and Lipowski (1974, 1981, 1983). This model, expanded by Barron and White (1996), has evolved into the model of advanced practice nurse consultation shown in Figure 9-1. This model is based on the following principles of consultation derived from the field of mental health (Caplan, 1970; Caplan & Caplan, 1993; Lipowski, 1981): • The consultation is usually initiated by the consultee. • The relationship between the consultant and consultee is nonhierarchical and collaborative. • The consultant always considers contextual factors when responding to the request for consultation. • The consultant has no direct authority for managing patient care. • The consultant does not prescribe, but makes recommendations. • The consultee is free to accept or reject the recommendations of the consultant. APNs tend to have a holistic orientation and understanding of systems theory that enables them to apply this consultation model in practice. At the center of Barron and White’s (1996) proposed model are the purposes and outcomes of consultation. Surrounding the center is the ecologic field of the consultation. Consultations are embedded in the context of the specific circumstances surrounding the consultation request, so the ecologic field in which the consultation takes place must be understood to provide effective consultation (Caplan & Caplan, 1993). This involves an appreciation of the interconnection and interrelatedness of the systems and contexts influencing the consultation problem and process. Thus, the consultation process is an integral part of the ecologic field. The process—in which the consultant evaluates the request, performs an assessment, determines the skills required to address the problem, intervenes, and evaluates the outcome—is expanded in Figure 9-2. Other elements of the ecologic field include the characteristics of the consultant, consultee, patient and family, and situational factors. We assume that there are reciprocal influences among the purposes, process, and contextual factors that can affect consultation processes and outcomes. Each component of the model is elaborated in the following sections. Figure 9-2 presents an algorithm of the consultation process. With experience and expertise, the process may occur fairly rapidly so that the expert consultant may not be consciously aware of using these steps. In addition, in some situations, the problem for which help is sought is clear-cut and the consultation is brief. These types of consultations are discussed later in the chapter. In addition to theoretical understanding, self-awareness and interpersonal skills are essential for the consultant (Barron, 1989; Barron & White, 2009). For a model of consultative practice to be implemented, it is critical that APNs first value themselves and the specialized expertise that they have developed. One must appreciate one’s own skills and knowledge before the possibilities for consultation can be envisioned (see Chapters 3 and 7). APNs have developed specialized expertise in the following: direct care of underserved populations, such as the homeless; frail older adults; persons who are chronically mentally ill, home-bound, or institutionalized; and patients with HIV infection. The knowledge and skills acquired by APNs could serve to inform and expand the practices of staff nurses, other APNs, and health care professionals of various disciplines involved in the care of these populations of patients. However, APNs must first appreciate that they have valuable understanding and knowledge to share. The consultant should also be able to establish warm, respectful, and accepting relationships with consultees (Carter & Berlin, 2007; Perry, 2011). The initiation of a consultation request is often associated with a sense of vulnerability on the part of the consultee, who recognizes that assistance is required to help manage the situation at hand. The consultant must communicate (and sincerely believe) that the problem and consultee are important and worthy of consideration. The consultant must also communicate confidence in the consultee’s ability to overcome the difficulties resulting in the consultation request. When the consultant creates a climate of trust and acceptance, the consultee can then be willing to risk vulnerability and genuineness with the consultant. When a respectful trusting connection is made between the consultant and consultee, a deep examination of the problem, implications, and solutions is possible. To be an effective consultant, an APN must be knowledgeable about systems, relationships, and change (see Chapter 11). Although skill in consultation develops over time, the attributes of the consultant and consultation process described here can help novice APNs who are open to learning approach consultation with confidence (see later, “Developing Consultation Skills in Advance Practice Nurse Students”; Carter & Berlin, 2007).

Consultation

Consultation and Advanced Practice Nursing

Defining Consultation

![]() TABLE 9-1

TABLE 9-1

Distinguishing Consultation from Comanagement, Referral, and Collaboration*

Background

Types of Consultation

Consultation and Specific Advanced Practice Nurse Roles

Model of Advanced Practice Nursing Consultation

Ecologic Field of the Consultation Process

Consultation Process for Formal Consultation

Characteristics of the Advanced Practice Nurse Consultant

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Consultation

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access