Confirmation and validation of empiric knowledge using research

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Chinn/knowledge/

Research extends knowledge through application of scientific methods—not with absolute certainty—but with minimal misinformation. Skepticism, alert self-criticism, constant testing of hypotheses by empirical research and awareness of limitations of science make research a most dependable source of information.

Laurie M. Gunter (1964, p. 231)

The opening quote by Gunter affirms both the significance of research as an application of the scientific method and its limitations. Gunter assumes that research—to produce the most dependable information—must be carefully performed, but even then the information that it provides is limited. Misinformation, according to Gunter, comes about when research methods are not carefully accomplished (for her, by the constant testing of hypotheses) but also when researchers do not have an attitude that involves questioning their motives, goals, and biases. Gunter also recognizes the inherent limitations of even the best research. For Gunter, three things create limitations in research: (1) shoddy methodologies, (2) problematic personal characteristics of researchers, and (3) the inherent nature of scientific research.

In previous chapters, we addressed the limitations of science and empirics as forms of knowledge. Although scientific research and empiric knowledge are most certainly important, empirics is limited to knowledge about abstracted generalities. In other words, empiric knowledge informs us about what we could usually expect to happen in a given situation. It is this feature of scientific empiric knowledge—its focus on the general—that makes empirics and research that leads to empiric knowledge both limited and powerful. Knowledge that is generated from scientific research is powerful precisely because it does relate to the usual or the general; it is limited because it requires other patterns of knowing in clinical practice. This chapter focuses on those methodologic features of empiric research that will result in a product that is minimally misinformative. The skepticism and alert self-criticism of the researcher along with careful methodologic consideration help to ensure that the outcomes of research are as accurate as possible.

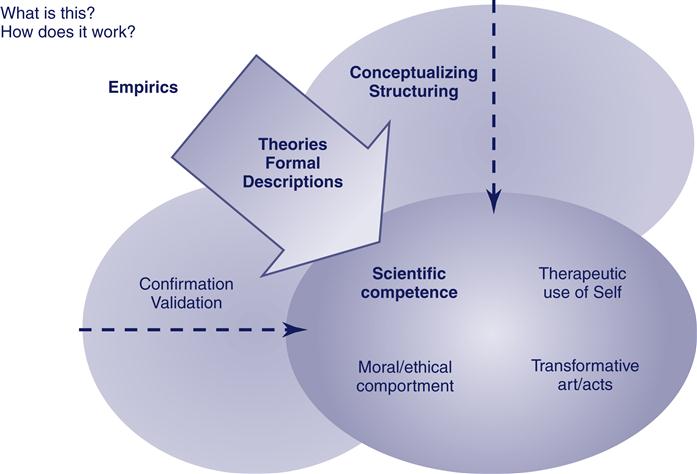

This chapter focuses on research methods for confirming and validating empiric phenomena. Figure 9-1 shows the empiric quadrant of our model for nursing knowledge development, which highlights the role of confirming and validating theories, formal descriptions, and other forms of empiric knowledge. These processes authenticate what is expressed in the formal knowledge of the discipline, which in turn strengthens scientific competence in practice. The confirmation and validation of empiric knowledge also draw on practice-based methods, which we present in Chapter 10. The research and practice-based methods, taken together, provide a strong foundation for nursing practice.

We use both confirmation and validation to characterize authentication processes within the empiric pattern. Their meanings are similar, yet there are important differences. Confirmation is the term that is reserved for the authentication of more qualitative and naturalistic forms of empiric research findings, whereas the term validation is used to refer to authentication processes for more quantitative, measurable forms of empiric research findings. Qualitative and naturalistic inquiry processes may result in knowledge that can already be considered confirmed, depending on the inquiry method used as well as the nature of the findings. Alternatively, additional clinical confirmation may be needed for some qualitative and naturalistic research findings. For the purposes of this text, confirmation and validation can be considered to be similar processes.

The development of empiric knowledge depends on systematic methods of inquiry. Research can be used as a means of testing empiric knowledge and as a method of generating the concepts and relationships for empiric knowledge structures that are being developed. Sound empiric knowledge development requires that the researcher make deliberate choices that link the underlying philosophies of science and nursing with research methods, theory, and practice.

Of all of the processes of empiric knowledge development, research-related activities are more visible to the casual observer than are the cognitively based theoretic processes. The concept of research is often associated with the image of a laboratory in which experiments are conducted or where some other activity that involves discovering facts occurs. In actuality, creating empiric knowledge is more related to abstract theoretic processes than it is to uncovering isolated facts that can be reported in great detail and with numbers. Factual knowledge is useful, but facts alone are not sufficient for the development of useful empiric knowledge. To develop empiric knowledge that is valuable for practice, facts and observations must be interpreted or made meaningful in relation to one another. It is theory that helps to place facts and isolated observations into meaningful interrelationships (Box 9-1).

In the next section, we distinguish between theory-linked and isolated research. The remainder of the chapter reviews the processes that are required to refine concepts and theoretic relationships with the use of empiric research methods, and we review approaches that will help to ensure that any given research project fulfills sound standards of theoretic adequacy. Throughout the remainder of the chapter, we use the term theory in a way that is consistent with our broad definition to include a wide range of empirically grounded knowledge structures.

Theory-linked research and isolated research

Research, like theorizing, can be conducted in a variety of ways and with many motivations. There are many types of research, and each research text presents a somewhat different way of viewing the total process. The traits that are common to each approach reflect certain basic standards that have been established to obtain results that are considered confirmable, valid, and accurately representative of empiric phenomena.

Any of the accepted research methods that are described in methods textbooks can be used with a theoretic link. The major trait that distinguishes theory-linked research from research that is not linked to theory (i.e., isolated research) is that theory-linked research is designed to extend, examine, develop, or validate a theory. This quality sets the stage for research studies to contribute to the larger knowledge of the discipline. By contrast, isolated research is not linked to the processes of theory development.

From a research point of view, theory-linked and isolated research can both be of excellent quality. Both types of research can ultimately contribute to knowledge, although isolated research is much more limited with regard to the contribution that it can make to a discipline. Because theory-linked research is conceived and conducted to extend, examine, develop, or validate theory, the findings of research imply significance at an abstract level of understanding. The research findings are not only useful in relation to the research problem or question, but they are also valuable for the development of the theory or for speculation about other situations in which the theory might be tested or applied.

In isolated research, the research problem is not linked to theory in any deliberate way. Rather, the investigator formulates questions or hypotheses and uses accepted methods to refute or support the hypotheses or to answer the questions. When theory is used as a loose guide to spark ideas for research questions, we would consider the research to be isolated. Isolated research can be useful to solve a problem (e.g., to determine the major sources of infection on a unit) or to provide initial evidence on which to build theory-linked research (e.g., to confirm the traits of a concept or phenomenon). The results of isolated research can provide new insights that prompt the researcher or someone reading a report of the research to speculate about the larger implications of the research, which in turn can lead to the development of a theory that has broader meaning for the discipline.

For research to be theory linked, the researcher must intend to extend, examine, develop, or validate theory, and deliberate linkages to the theory must be made during the process of research development. Questions or hypotheses may come from the practical circumstances that surround the investigator’s work, the imagination, an idea that occurred as the investigator read other research results, or any number of other sources. These same factors can also provide direction throughout the ongoing process of the development of theory-linked research.

All research is confined to a particular place and time in history. Because theories are constructions of the mind, they can transcend—to a certain extent—the limitations of time and space. The cultural and historical circumstances of the theorist influence the mental construction of the theory, but, because the theory is an abstraction, it can be generalized beyond the limits of particular circumstances.

Theory-linked research has advantages that overcome the limitations of the specific place and time in which the research occurs. Theory-linked research hypotheses that are developed from abstract statements within a theory represent a translation of the theory’s statements to the circumstances of the specific study. Theory-generating research studies culminate with a linkage to theory by organizing study data into a more abstract theoretic structure. Theory-linked research findings can be generalized only within limits, just like those reported in isolated research. However, the study findings in theory-linked research can be retranslated into theoretic terms and implications that are discussed in relation to the theory.

Challenges related to theory-linked research

Although theory-linked research has definite advantages over isolated research with regard to its ability to contribute to the development of knowledge, certain hazards and challenges are unique to this type of research.

Inappropriate use of theories

It is possible to use a theory inappropriately in conducting research. For example, if a theory is designed to explain animal behavior, it may not be appropriate as a basis for explaining or understanding human behavior without sufficient conceptual examination. Theory and theoretic concepts that are used inappropriately lead to erroneous conclusions. For example, Reed (1978) described how some theories in the behavioral sciences have resulted in erroneous information about primate behavior. With the use of theories of human behavior, researchers categorized primate sexual behavior as monogamous or polygamous to be consistent with the normative expectations for human behavior. On the basis of limited observations of animal behavior, it became common practice to describe animal behavior with these terms. Reed pointed out that, in reality, primates seldom cohabit on the basis of sex differences and that the segregation of male and female primates is more pronounced than cohabitation. Theories sometimes provide a mental set that clouds observations or skews interpretations of meaning, especially if the theory is assumed to be true or consistent with prevailing values.

Theories as barriers

Theories can obscure a researcher’s ability to notice certain features of data or events. The mindset provided by the theory, whether appropriate or not, may preclude the recognition of other possibilities. When the focus is on expected outcomes, unless something startling or drastically different occurs, some elements may not be noticed. For example, you can view a child’s behavior and, because of a certain theory, assume that what you observe is problem-solving ability. At the same time, you might fail to notice other things about the child’s behavior that are not brought to your attention by the theory. These other behaviors might include less obvious and therefore easily overlooked actions, such as body posture, facial expressions, or eye motion. It is possible that qualities of these behaviors relate to problem-solving ability, but the mental set that you acquire from the theory focuses your attention on limited behaviors, and something potentially important to understanding the child’s experience is overlooked. If you are conducting a grounded-theory study with the purpose of uncovering the parental processes of attributing blame when teenaged children join gangs, your background knowledge of the socialization patterns of adolescents will influence how you interpret and understand the data obtained from interviewing the parents.

Paradoxically, although a theory may be useful and appropriate for understanding certain phenomena, it may limit your thinking about the range of possibilities for interpreting and understanding a situation or experience. Overcoming this difficulty requires you to constantly question what you read, think, and observe. Theory is not intended to represent phenomena and events exactly; it is intended to be an approximation and a tool that can be used to see possibilities. The purpose for using research to develop theory is to discover to what extent a theory can be regarded as sound and how it functions to reveal new possibilities.

Ethical considerations

Theories can also exceed acceptable limits of reality; theories as mental constructions may relate ideas that cannot or should not be tested out of respect for human and animal rights and dignity. For example, given the threat of nuclear accidents, you might imagine that it would be useful to predict events in a large population of people who experience significant exposure to radiation and that this knowledge might help to prepare for such circumstances. However, it is not ethical to subject humans or animals to such an experience to develop theory. It also is not feasible to test imagined theoretic ideas that claim to predict the consequences of exposure to radiation. Ethical considerations may also be much subtler and need to be examined. For example, certain approaches to the study of cultures outside of the mainstream (e.g., persons who are hearing impaired, ethnic minority groups, gay or lesbian cultures) undermine those cultures and provide avenues for further discrimination. In addition, ethical considerations may curtail a study when interim findings suggest that its continuation is likely to harm participants.

Occasionally historical circumstances provide evidence that is used to develop useful theory, but further development is limited by concern for human and animal welfare. Theories of mother–infant attachment and separation grew out of the experiences of wartime children who were separated from their mothers for extended periods. Subsequent to the destruction of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, the effects of exposure to toxins in the rubble among rescue personnel and canines are being studied. The evidence that grows out of historical disasters can demonstrate their harmful effects, but research that replicates similar circumstances is ethically indefensible.

Refining concepts and theoretic relationships

A particular type of theory-linked research is research that is designed specifically to refine concepts and theoretic relationships. These types of investigations are crucial early during the stages of a theory’s development, but they can be used at any point throughout the process. Refining concepts and theoretic relationships involves a focus on the correspondence of the ideas of the theory with perceptible sensory experience (Dubin, 1978; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Newman, 1979; Reynolds, 1971/2006). Because empiric concepts and theories are abstractions of what can be observed or perceived during an experience, a translation is made from the theoretic to the empiric (i.e., the deductive approach) and from the empiric to the theoretic (i.e., the inductive approach).

To function as viable structural elements of theory, concepts must adequately represent experience. Both quantitative and qualitative descriptive approaches are typically used to obtain empiric evidence that the concepts as created within the theoretic structure have adequate empiric indicators. The evidence from the investigations may suggest the use of processes of creating conceptual meaning to better represent the experience. Investigations that are designed to develop and refine empiric indicators and operational definitions of concepts are crucial for adequate research to refine and validate theoretic relationships.

Theoretic relationships, which connect two or more concepts in a specific structure, are directly influenced by the nature of the empiric indicators for the concepts that are being related. The activities of refining concepts and theoretic relationships involve both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Replication requires repeating the confirmation or validation activities in other contexts. Theoretic relationships cannot be proven, but it is possible to show empiric support for proposed relationships. If the evidence does not support theoretic relationships, the ideas of the theory cannot be sustained. Alternative theoretic explanations are then considered on the basis of the empiric evidence.

Refining concepts and theoretic relationships draws on one or more of the following subcomponents: (1) identifying empiric indicators for the concepts, (2) empirically grounding emerging relationships, and (3) validating relationships with the use of empiric methods.

Identifying empiric indicators

Empiric indicators and operational definitions are used to represent concepts as variables in empiric research, and they are empirically formed for concepts as an outcome of some inductive research approaches. Formally structured theory can propose empiric indicators, but until those indicators are put into operation in research, they remain speculative. Making use of the ideas in actual research makes it possible to refine the theory.

Consider the following abstract relationship statement:

As the adult’s eye contact increases, the infant’s eye contact will increase.

Imagine that a research project is designed to obtain empiric evidence about the use of eye contact as an empiric indicator of mothering. Details such as length of gaze and frequency of eye contact could be specified for the relatively abstract concept of eye contact. To use these indicators, the researcher would create a method for observing and timing the length of gaze and the frequency of eye contact.

Part of the process for identifying empiric indicators, especially when primarily deductive processes are used, is to state operational definitions. Operational definitions specify the standards or criteria to be used when making the observations. For example, an operational definition of the term gaze might be “a steady, direct, visual focusing on an object that lasts at least 3 seconds.” This definition indicates what gaze is (the empiric indicator for visual contact), the characteristics that must be present to call a behavior a gaze (direct visual focusing on an object), and a standard time parameter that distinguishes a gaze from other related behaviors, such as a glance or a look.

It is difficult to identify empiric indicators for concepts that are more abstract than the concept of eye contact. Many concepts related to nursing (e.g., anxiety, body image, self-esteem) are highly abstract and cannot be directly measured. Tests and tools have been constructed to provide an indirect estimate of traits such as these. The fact that they cannot be measured directly does not mean that they are nonexistent or that they cannot be assessed. The empiric challenge is to refine ideas about and evidence for empiric indicators so that the strength of the relationships can be explored.

The difficulties of finding adequate empiric indicators for abstract concepts can be compared with trying to describe the taste of a tomato. After a person bites a tomato, that person knows how a tomato tastes. As another example, after a nurse smells a purulent wound, that nurse recognizes that smell as being associated with a wound that is not healing well. The descriptions of these specific tastes and smells are not at all adequate for comparison with the actual taste or smell experiences.

Many of the concepts that are important for nursing are highly abstract, and even the actual experiences are not clearly perceived. Subsequently, the problem of finding adequate empiric indicators becomes complex and difficult. For example, anxiety is an abstract concept that can be theoretically defined. However, when we explore the experience of anxiety, we find that, although people recognize what we mean by the term anxiety, the actual experiences of anxiety are elusive to describe, much like trying to describe the taste of a tomato. Nevertheless, if the concept is important for nursing, empiric knowledge development depends on diligent efforts to make visible, as accurately as possible, the link between the abstract concept and the contextualized human experience. These examples underscore the value of creating conceptual meaning for adequate theory in nursing.

One approach that can be used to derive empiric measures for abstract nursing concepts is to use multiple empiric indicators to form useful research definitions. For example, anxiety might be measured with a self-report tool. The tool can be constructed to include many sensations that are generally indicative of anxiety. An operational definition of the concept of anxiety then becomes “what is assessed with the use of the tool.” Anxiety may also be assessed empirically by observing a person’s behavior and appropriate physiologic indicators of neuroendocrine function. In this case, operational definitions would include specific ways to measure the behaviors observed and the specific range of laboratory test results associated with anxiety. All of these empiric indicators are possible. If they are used together in situations in which anxiety is likely to occur, the study will provide substantive evidence about the usefulness of each measure as an empiric indicator.

It is important to recognize that the empiric indicators identified for concepts must consider the theory that is to be validated. For example, if the concept of caring in the context of Madeleine Leininger’s theory needs to be empirically assessed, it would be counterproductive to use a tool to assess caring that was developed for use with Jean Watson’s theory. In addition, dictionary definitions are generally not a good source of empiric indicators for concepts. In other words, when concepts are operationalized, they must be defined and measured in concert with the meaning of the theory in which they are embedded; not just any approach to measurement will do.

When inductive research processes form the basis for refining empiric indicators, the indicators are directly or indirectly observed and then used to form concepts. Knowing the empiric indicators that are used to generate the concepts would assist with the deductive testing and the extension of the theory into other contexts.

The work of Ferrans (1997) and Ferrans and Powers (1992) in developing the concept of quality of life is an example of the use of several different research approaches to develop and refine a conceptual model. Quality of life is a complex construct that requires a complex set of empiric indicators and operational definitions. Ferrans used qualitative research methods to find out what indicators people from different cultural groups associated with the idea of quality of life. Ferrans and Powers also used the statistical technique of factor analysis to identify how various indicators clustered together within domains. With the use of factor analysis, they identified four domains (factors) associated with quality of life: (1) health and functioning, (2) psychologic and spiritual, (3) social and economic, and (4) family. They then developed a tool, the Quality of Life Index, to assess and measure the concept of quality of life within these four domains.

Empirically grounding emerging relationships

The process of empirically grounding emerging relationships involves connecting experiences with representations of those experiences. When an abstract theoretic relationship is taken as the starting point, the investigator designs a study in which the hypothetic relationship, when framed in terms of the empiric indicators for the concepts, can be studied. Several investigations may be required to confirm that the relationship that has been proposed is accurate. When the investigations provide sufficient empiric evidence that conclusions can be drawn about the relationship, the investigator can return to the theoretic ideas and refine the theoretic statements to reflect what has been supported empirically. These conclusions are often presented as examples that accompany citations of the empiric investigations within the narrative explanations of the theory.

An investigator can begin by exploring a selected empiric situation as a starting point, with the goal of finding the concepts and relationships that accurately represent a situation that is not yet clearly understood but that is recognized as important to the discipline of nursing. The investigator selects a social context in which the phenomenon under consideration is likely to occur and observes the interactions and circumstances of that context. From the observations, the investigator derives relationship statements that are grounded in the available empiric evidence. A variety of inductive approaches can be used to ground emerging relationships (Denzin & Lincoln, 2007; Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Validating relationships through empiric methods

Validating theoretic relationships requires creating a design that tests the descriptive and explanatory powers of a designated relationship. Designs may be proposed after a theory is structured (i.e., deduction). When the purpose of the research design is to use inductive methods to generate theoretic relationships, the relationships are considered to be confirmed and ready for replication and additional confirmation in other settings.

A key to the deductive validation of theoretic relationships is to use a design that ensures that the proposed relationship is actually the one that accounts for the study findings. For example, if a study concludes that a mother’s gaze prompts an infant’s gaze in return, then the researcher needs to consider ways to be sure that it is actually the mother’s gaze that accounts for the infant’s behavior. Typically, the researcher designs the study so that other factors that could influence the behavior of the infants in the study (e.g., sensory experiences such as noise, touch, or visual distractions that might affect the process of visual interaction) are accounted for or held constant.

The purpose of deductively validating any relationship statement is to provide empiric evidence that the relationships proposed in the theory are adequate for a specific situation. With each approach to design that is used, the research question or hypothesis is revised to suit the type of design that has been selected. Empiric evidence that is based on many different approaches to research design provides a basis for judging the adequacy of the theory. If theoretic statements are deductively tested and not supported by empiric evidence, one or more of the following four possibilities can account for the disparity between the theory and the empiric findings: