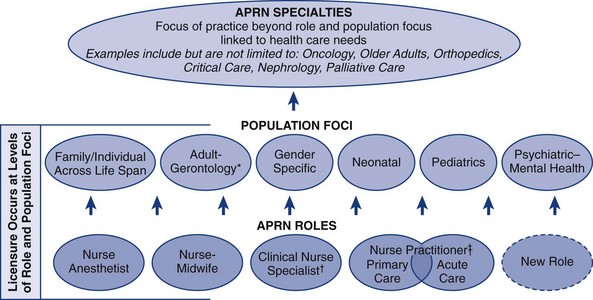

Chapter 2 Nature, Purposes, and Components of Conceptual Models Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing: Problems and Imperatives Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing Roles: Organizational Perspectives Consensus Model for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Regulation American Association of Colleges of Nursing National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists American Association of Nurse Anesthetists and American College of Nurse-Midwives International Organizations and Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing Section Summary: Implications for Advanced Practice Nursing Conceptualizations Conceptualizations of the Nature of Advanced Practice Nursing Hamric’s Integrative Model of Advanced Practice Nursing Fenton’s and Brykczynski’s Expert Practice Domains of the Clinical Nurse Specialist and Nurse Practitioner Calkin’s Model of Advanced Nursing Practice Brown’s Framework for Advanced Practice Nursing Strong Memorial Hospital’s Model of Advanced Practice Nursing Oberle and Allen: The Nature of Advanced Practice Nursing Shuler’s Model of Nurse Practitioner Practice Ball and Cox: Restoring Patients to Health—A Theory of Legitimate Influence Section Summary: Implications for Advanced Practice Nursing Conceptualizations Models Useful for Advanced Practice Nurses in Their Practice American Association of Critical-Care Nurses’ Synergy Model Advanced Practice Nursing Transitional Care Models Dunphy and Winland-Brown’s Circle of Caring: A Transformative, Collaborative Model Recommendations and Future Directions Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing Consensus Building Around Advanced Practice Nursing Consensus on Key Elements of Practice Doctorate Curricula Research on Advanced Practice Nurses and Their Contributions to Patient, Team, and Systems Outcomes The development of a common language and conceptual framework for communication and for guiding and evaluating practice, education, policy, research, and theory is fundamental to sound progress in any practice discipline. Given the evolving changes in the U.S. health care system, such a foundation is particularly crucial at this stage in the development of advanced practice nursing. Since the last edition, a professional consensus on advanced practice nursing regulation has been reached in the United States—the Consensus Model for APRN Regulation (2008) and is being implemented. In addition, the Institute of Medicine [IOM] (2011) has called for integrating advanced practice nursing more completely into the U.S. health care delivery system. Other forces driving a common understanding of advanced practice nursing are the expansion of programs offering the Doctorate of Nursing Practice (DNP), the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA, 2010), accountable care organizations, and the promulgation of interprofessional competencies (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative [CIHC], 2010; Health Professions Networks, Nursing and Midwifery, & Human Resources for Health, 2010; Interprofessional Education Collaborative [IPEC] Expert Panel, 2011) and education (see Chapters 12 and 22). Understanding what advanced practice nursing is, what APNs do, similarities and differences among APNs, and how APNs contribute to affordable, accessible, and effective care is central to the redesign of U.S. health care. It is important for readers to understand that because of the dynamic and evolving nature of health care reform and nursing organizations‘ activities in this arena, nationally and globally, the content in this chapter is changing quickly. Readers are encouraged to consult the websites cited in this chapter for up to date information. Internationally, there have been efforts to clarify, establish, and/or regulate advanced practice roles within the nursing profession in other countries (e.g., Canadian Nurses Association [CNA] 2007, 2008, 2009a, b; International Council of Nurses [ICN] (2009). In countries in which APN roles exist, in addition to studies of the distinctions among roles (Gardner, Chang, & Duffield, 2007; Gardner, Gardner, Middleton, et al., 2010), efforts are underway to establish educational programs (Wong, Peng, Kan, et al., 2009) or develop frameworks that clarify education, scope of practice, registration and licensing, and/or credentialing that are country-specific (e.g., Fagerström, 2009). Statements by national organizations such as the CNA and ICN and articles on conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing proposed by authors from other countries (e.g., Ball & Cox, 2004; CNA, 2007, 2008, 2009a, b; DiCenso, Martin-Misener, Bryant-Lukosius, et al., 2010; Gardner, Chang, & Duffield, 2007; Gardner et al., 2010; Mantzoukas & Watkinson, 2007; McMurray, 2011; Pringle, 2010) have been reviewed. Although contextual factors may differ from those in the United States, there are global opportunities for clarifying and advancing advanced practice nursing and these should be specific to a country’s culture, health system, professional standards, and regulatory requirements. Content from articles about advanced practice in other countries is used to present models or illuminate certain conceptual issues; they also inform the discussion of recommendations and future directions. For a more complete discussion of global perspectives on advanced practice nursing, see Chapter 6. In reviewing the literature for this edition, searches were conducted using the terms advanced practice nursing, model, or theory, and the four APN roles. In addition, a search was done of the authors of models cited in the prior edition. Few new curricular models were identified (Fagerström, 2009; Perraud, Delaney, Carlson-Sabelli, et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2009), but several types of articles related to model development, model testing, and models used in advanced practice nursing were identified. These models may be characterized as follows: • Curriculum models (e.g., Fagerström, 2009; Perraud et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2009) • Administrative or organizational models (e.g., Ackerman, Mick, & Witzel, 2010; Scarpa & Connelly, 2011; Skalla & Caron, 2008) • Models that differentiate among advanced practice roles (e.g., Gardner, Chang, & Duffield, 2007) • Models of the nature of advanced practice nursing (e.g., Ball & Cox, 2003; Brown, 1998; Hamric, 1996, 2009, and see Chapter 3; Mantzoukas & Watkinson, 2007; Styles & Lewis, 2000) • Models that differentiate between basic and advanced practice nursing (e.g., Calkin, 1984; Oberle & Allen, 2001) • Models of role development of APNs (see Chapter 4) • Models of APN regulation and credentialing (e.g., the APRN [Advanced Practice Registered Nurse] Consensus Model, 2008; CNA, 2007, 2008, 2009a, b; Stanley, Werner, & Apple, 2009; Styles, 1998); • Models of interdisciplinary practice (Dunphy & Winland-Brown, 1998; Dunphy, Winland-Brown, Porter, Thomas, & Gallagher, 2011); • Models that APNs would find useful include the following: • Models to evaluate outcomes of advanced nursing practice (see Chapters 23 and 24). In previous editions, problems associated with lack of a unified definition of advanced practice and imperatives for undertaking this important work were identified. When practicable, consensus on advanced practice nursing models should be beneficial for patients, society, and the profession. Although the APRN Consensus Model (2008) has brought needed conceptual clarity to regulation of advanced practice nursing in the United States, there is still work to be done with regard to other aspects of conceptualizing advanced practice nursing, such as APN competencies, differentiating basic and advanced nursing practice, and differentiating the advanced practice of nursing from the practices of other disciplines. This work has become more urgent given the impacts of other U.S. initiatives that are unfolding. I have reviewed published documents from national professional organizations and the literature and focused selectively on models of APN practice. This review is not exhaustive. For example, in limiting the scope of this chapter, statements on advanced practice nursing by specialty organizations have not been examined. Thus, the purposes of this chapter are as follows: 1. Lay the foundation for thinking about the concepts underlying advanced practice nursing by describing the nature, purposes, and components of conceptual models. 2. Identify conceptual challenges in defining and operationalizing advanced practice nursing. 3. Describe selected conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing. 4. Make recommendations for assessing existing models and developing, implementing, and evaluating conceptual frameworks for advanced practice. 5. Outline future directions for conceptual work on advanced practice nursing. A conceptual model is one part of the structure, or holarchy, of nursing knowledge. This structure consists of metaparadigms (most abstract), philosophies, conceptual models, theories, and empirical indicators (most concrete; Fawcett, 2005). Traditionally, key concepts in the metaparadigm of nursing, which nursing theories are expected to address in their conceptual underpinnings, are humans, the environment, health, and nursing (Fawcett, 2005). Although some theorists have proposed additional or expanded concepts, Fawcett’s ideas inform this discussion. At this stage of the evolution, conceptual models of advanced practice nursing remain an appropriate focus. A number of answers to these questions are in the nursing literature. Fawcett (2005) has identified a conceptual model as “a set of relatively abstract and general concepts that address the phenomena of central interest to a discipline, the propositions that broadly describe these concepts, and the propositions that state relatively abstract and general relations between two or more of the concepts” (p. 16). Fawcett (2005) also noted that a conceptual model is “a distinctive frame of reference…that tells [adherents] how to observe and interpret the phenomenon of interest to the discipline” and “provide alternative ways to view the subject matter of the discipline; there is no ‘best’ way.” Although there is no best way to view a phenomenon, evolving a more uniform and explicit conceptual model of advanced practice nursing is likely to benefit patients, nurses, and other stakeholders (IOM, 2011) and have practical benefits. It can facilitate communication, reduce conflict, ensure consistency of advanced practice nursing, when relevant and appropriate, across APN roles, and offer a “systematic approach to nursing research, education, administration, and practice” (Fawcett, 2005). Thus, conceptual models serve many purposes. Models may help APNs articulate professional role identity and function, serving as a framework for organizing beliefs and knowledge about their professional roles and competencies, providing a basis for further development of knowledge. In clinical practice, APNs use conceptual models in the delivery of their holistic, comprehensive, and collaborative care (e.g., Carron & Cumbie, 2011; Dunphy & Winland-Brown, 1998; Dunphy et al., 2011; Musker, 2011). Models may also be used to differentiate among levels of nursing practice—for example, between staff nursing and advanced practice nursing (Calkin, 1984; ANA, 2010b). In research and other scholarly activities, investigators use conceptual models to guide research and theory development. An investigator could decide to focus on the study of one concept or examine relationships among select concepts to elucidate testable theories. For example, research by Fenton (1985) and Brykczynski (1989) has elucidated new domains of practice for clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) and nurse practitioners (NPs), respectively. In education, faculty use conceptual models to plan curricula, identify important concepts and the relationships among them, and make choices about course content and clinical experiences for preparing APNs (Perraud et al. 2006; Wong et al., 2009). Fawcett and colleagues (Fawcett, Newman, & McAllister, 2004; Fawcett & Graham, 2005) have raised additional conceptual questions about advanced practice: • What do APNs do that makes their practice “advanced?” • To what extent does incorporating activities traditionally done by physicians qualify nursing practice as “advanced?” Because direct clinical practice is viewed as the central APN competency, one could also ask: “What does the term clinical mean? Does it refer only to hospitals or clinics?” These questions are becoming more important given the APRN Consensus Model and given the role that APNs are expected to play across the continua of health care as a result of the PPACA and its reforms. From a regulatory standpoint, the emphasis on a specific population as a focus of practice will lead, when appropriate, to reconceptualizing curricula to ensure that graduates are prepared to succeed in new or revised certification examinations. Hamric (see Chapter 3) has noted that some APN competencies are likely to be performed by nurses in other roles but suggests that the expression of these competencies by APNs is different. For example, all nurses collaborate but a unique aspect of APN practice is that APNs are authorized to initiate referrals and prescribe treatments that are implemented by others (e.g., physical therapy). Innovations and reforms arising from the PPACA will ensure that APNs are explicitly engaged in the delivery of care across care settings, including in nursing clinics and palliative care settings, and as full participants in interprofessional teams. Changes in regulations and in the delivery of health care must and should lead to new or revised conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing, such as defining theoretical and evidence-based differences between APN care and the care offered by other providers and clinical staff, the role of APNs in interprofessional teams, and specialization and subspecialization in advanced practice nursing. This work will enable nursing leaders and health policy makers to design a health care system that delivers high-quality care at reasonable cost based on disciplinary and interdisciplinary competencies, outcomes, effectiveness, efficacy, and costs. Indeed, this textbook reflects a consistent effort to evaluate and revise the authors’ conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing based on current contextual factors. The conceptualization advanced in this text has been remarkably stable since it was first proposed in 1996 and has required modest modifications as APN roles and health care have evolved. In addition to a pragmatic reevaluation of advanced practice nursing concepts based on the evolution of APN regulation and health care reform, writers in the United States and abroad are raising important theoretical questions about conceptualizations of advanced practice, including the following: the epistemologic, philosophical, and ontologic underpinnings of advanced practice (Arslanian-Engoren, Hicks, Whall, & Algase, 2005); the nature of advanced practice knowledge, discerning the differences between and among the notions of specialty, advanced practice, and advancing practice (Allan, 2011; Christensen, 2009, 2011; Macdonald, Herbert, & Thibeault, 2006; Thoun, 2011); and the extent to which APNs are prepared to study and apply nursing theories in their practices (Algase, 2010; Arslanian-Engoren, Hicks et al., 2005; Karnick, 2011). In summary, questions arising from a changing health policy landscape and from theorizing about advanced practice nursing point to the need for well thought-out, robust conceptual models to help individuals answer important questions about the phenomenon—in this case, advanced practice nursing. The need for clarity about advanced practice nursing, what it is and is not, is becoming more important, not only for patients and those in the nursing profession but for evolving initiatives such as interprofessional education (CIHC, 2010; Health Professions Networks, 2010; IPEC Expert Panel, 2011), practice (American Association of Nurse Anesthetists, 2012), and creation of accountable care organizations, efforts to build teams and systems in which effective communication, collaboration, and coordination lead to quality care and improved patient, institutional, and fiscal outcomes. Despite improvements in the area of regulation, the first issue remains the absence of well-defined and consistently applied terms of reference. A core stable vocabulary, a lingua franca, is needed for definition and model building. The lack of a consistent stable vocabulary can be seen in the literature. Shuler and Davis (1993a) have stated that “One of the greatest barriers to using nursing models in [nurse practitioner] practice relates to vocabulary and communication….” Despite progress, this challenge remains. For example, in the United States, advanced practice nursing is the term that is used but the ICN and CNA use the term advanced nursing practice. Furthermore, the role and functions of APNs could be better conceptualized. Although the use of competency is becoming more common, concepts about APN work are variously termed roles, hallmarks, competencies, functions, activities, skills, and abilities. Few models of APN practice address nursing’s metaparadigm (person, health, environment, nursing) comprehensively. The problem in comparing, refining, or developing models is that terms are used with no universal meaning or frame of reference; occasionally, no definition is offered at all, or terms are used inconsistently. This instability and inconsistency are evident in many models cited in this chapter. It is rightly anticipated that conceptual models of the field and its practice change over time. However, the evolution of advanced practice nursing and its comprehension by nurses, policymakers, and others will be enhanced if scholars and practitioners in the field agree on the use and definition of fundamental terms of reference. • Does the practice of APNs differ from the practice of registered nurses (RNs) who are experts by experience (i.e., no graduate degree in advanced practice)? • How does the practice of an APN certified in a subspecialty such as oncology differ from the practice of a non–master’s prepared clinician who is certified at the basic level in the oncology subspecialty? • With the definition of population foci and subspecialty advanced in The APRN Consensus Model, how does certification in one or more subspecialties influence the quality and outcomes of care? • How does the care provided by an adult health NP with a subspecialty APN certification in oncology or critical care differ from one who is certified in adult health only? Although many authors who write about advanced practice nursing cite Benner’s model of expert practice (1984), they rarely indicate that the model was derived from the study of nurses who were primarily experts by experience, not APNs. Certainly, Benner’s model is relevant to efforts to conceptualize advanced practice nursing, as demonstrated by Fenton’s (1985) and Brykczynski’s (1989) work. Given that clinical practice is why the profession of nursing exists and is central to advanced practice nursing, models that help the profession differentiate levels of practice are needed. The fourth issue is the need to clarify the differences between advanced practice nursing and medicine (see Chapter 3). Graduate APN students struggle with this issue as part of role development (see Chapter 4). This lack of conceptual clarity is apparent in advertisements that invite NPs or physician assistants to apply for the same job. As noted in Chapters 21 and 22, organized medicine expends resources in trying to limit or discredit advanced practice nursing, even as some physician leaders work on behalf of advocating for APNs. Hamric, in Chapter 3, asserts that advanced practice nursing is not the junior practice of medicine, an assertion supported by the seven competencies of advanced practice nursing (Chapters 7 through 13). Fawcett, a well-respected nursing leader, has asked, “What does it mean to blend nursing and medicine?” (Fawcett et al., 2004; Fawcett & Graham, 2005). Finally, little is understood about the impact of APN-physician collaboration on practice or about strategies for matching the level of knowledge and skill to the needs of patient populations (Brooten & Youngblut, 2006; Calkin, 1984). The fifth issue is interprofessional education and practice, a concept that is central to accountable, collaborative, coordinated, and high-quality care. The development of interprofessional competencies for health professionals (CIHC, 2010; Health Professions Networks, 2010; IPEC Expert Panel, 2011) suggests that the more important questions now are not about “blending” APN and physician practice, but questions such as “How do we ensure that despite differing disciplinary backgrounds, patients, colleagues, and other observers recognize the behavioral expressions of interprofessional competencies?” Also, how do we undertake the conceptual, curricular, credentialing, and other work that will be needed to make interprofessional practice and effective teamwork the gold standard of quality care? The existence of interprofessional competencies and emergence of promising conceptualizations of interprofessional work. (e.g., Barr, Freeth, Hammick, et al., 2005; Reeves, Goldman, Gilbert, et al., 2011) are critical contextual factors for elucidating and advancing conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing. See Chapter 12. Among many imperatives for reaching a conceptual consensus on advanced practice nursing, most important are the interrelated areas of policymaking, licensing and credentialing, and practice, including competencies. In the policymaking arena, for example, not all APNs are eligible to be reimbursed by insurers, and even those activities that are reimbursable are often billed incident to a physician’s care, rendering the work of APNs invisible. The APRN Consensus Model (2008), the PPACA, and the IOM’s call for changes to enable APNs to work within their full scope of practice (IOM, 2011). will make it easier for U.S. policymakers to recommend and adopt changes to policies and regulations that now constrain APN practice, eventually making the contributions of APNs to quality care visible and reimbursable. Agreement on vocabulary and concepts such as competencies that are common to all APN roles will maximize the ability of APNs to work within their full scope of practice. 1. Clear differentiation of advanced practice nursing from other levels of clinical nursing practice. 2. Clear differentiation between advanced practice nursing and the clinical practice of physicians and other non-nurse providers within a specialty. 3. Clear understanding of the roles and contributions of APNs on interprofessional teams, enabling employers to create teams and accountable care organizations that can meet institutions‘ clinical and fiduciary outcomes. 4. Clear delineation of the similarities and differences among APN roles and the ability to match APN skills and knowledge to the needs of patients. 5. Regulation and credentialing of APNs that protects the public and ensures equitable treatment of all APNs. 6. Clear articulation of international, national, state, and local health policies that do the following: a. Recognize and make visible the substantive contributions of APNs to quality, cost-effective health care, and patient outcomes. b. Ensure the public’s access to APN care. c. Ensure explicit and appropriate mechanisms to bill and pay for APN care. 7. A maximum social contribution by APNs in health care, including improvement in health outcomes and health-related quality of life for the people to whom they provide care. 8. The actualization of practitioners of advanced practice nursing, enabling APNs to reach their full potential, personally and professionally. • What is the scope and purpose of advanced practice nursing? • What are the characteristics of advanced practice nursing? • Within what settings does this practice occur? • How do APNs’ scopes of practice differ from those of other providers offering similar or related services? • What knowledge and skills are required? • How are these different from other providers? • What patient and institutional outcomes are realized when APNs deliver care? how are these outcomes different from other providers? • When should health care systems employ APNs and what types of patients particularly benefit from APN care? • For what types of pressing health care problems are APNs a solution in terms of improving outcomes, quality of care, and cost-effectiveness? 1. Each model, at least implicitly, addresses the four elements of nursing’s metaparadigm—persons, health and illness, nursing, and the environment. 2. The development and strengthening of the field of advanced practice nursing depends on professional agreement regarding the nature of advanced practice nursing (a conceptual model) that can inform APN program accreditation, credentialing, and practice. 3. That APNs meet the needs of society for advanced nursing care. 4. Advanced practice nursing will reach its full potential to the extent that foundational conceptual components of any model of advanced practice nursing framework are delineated and agreed on. In the next section, the implicit and explicit conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing promulgated by professional organizations concerned with defining APN practice and with clarifying particular APN roles are discussed. Organizations such as the Oncology Nursing Society and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses [AACN]) have addressed advanced practice nursing in their specialties. Although specialty models and standards are important to students and APNs, they are not addressed in this chapter. As students and readers consider their own APN practices, they may want to review the history of advanced practice nursing (see Chapter 1) and evolving advanced practice nursing roles (see Chapter 5) to inform their efforts to conceptualize their own practices. Although not all the documents described in this section are conceptual models, many imply, describe, or reference a conceptual framework. The APRN Consensus Model (2008) represents a major step forward in promulgating a uniform definition of advanced practice nursing, for the purposes of regulation, in the United States. This accomplishment is informing efforts by other organizations; even so, some problems with the absence of a core vocabulary noted earlier are apparent as one reads the different approaches taken by other professional organizations; therefore, comparisons are difficult to make because terms of reference and their meanings vary. To help the reader appreciate the challenge of developing a common language to characterize advanced practice nursing, dictionary definitions of terms used in conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing are found in Box 2-1. In spite of differences in terminology, the efforts of the profession to deal with a definition of advanced practice nursing are evident in the documents reviewed here. Reflection on and discussion of the various terms used, and debate about interpreting terms such as roles, domains, and competencies, may contribute to the clarification of conceptual models and the emergence of a common language. The descriptions of each model in the following sections are necessarily limited. The reader is encouraged to refer to the original documents and organizations‘ websites to understand advanced practice nursing as described by organizations and individual authors more fully. Website addresses for national APN organizations are found in Chapter 21. The APRN Consensus Model, the result of collaboration of many organizations, is described first, because it will continue to guide and influence conceptualizations of advanced practice, at least with regard to regulation and credentialing, for the near future. In 2004, an APN Consensus Conference was convened, based on a request from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) and the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF) to the Alliance for APRN Credentialing. The purpose was to develop a process for achieving consensus regarding the credentialing of APNs (APRN Consensus Model, 2008; Stanley, Werner, & Apple 2009) and the development of a regulatory model for advanced practice nursing. Independently, the APRN Advisory Committee for the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) was charged by the NCSBN board of directors with a similar task of creating a future model for APRN regulation and, in 2006, disseminated a draft of the APRN Vision Paper (NCSBN, 2006), a document that generated debate and controversy. Within a year, these groups came together to form the APRN Joint Dialogue Group, with representation from numerous stakeholder groups, including AACN, NCSBN, and organizations representing APNs. The outcome was the APRN Consensus Model (2008). The APRN Regulatory Model includes important definitions, the roles and titles to be used, and population foci. Furthermore, it defines specialties and describes how to make room for the emergence of new APRN roles and population foci within the regulatory framework. In addition, a timeline for adoption and strategies for implementation were proposed, and progress has been made in these areas (see Chapter 21 for further information; only the model is discussed here). Figure 2-1 depicts the components of the APRN Consensus Model, the four recognized APN roles and six population foci. The term advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) refers to all four APN roles. An APRN is defined as a nurse who meets the following criteria (APRN Consensus Model, 2008): FIG 2-1 Consensus model for APRN regulation. This model was based on the work of the APRN Consensus Work Group and the NCSBN APRN Advisory Committee. (From APRN Joint Dialogue Group. [2008]. Consensus Model for APRN Regulation. [http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/APRNReport.pdf]).*The population focus Adult-Gerontology encompasses the young adult to the older adult, including the frail elderly. APRNs educated and certified in the Adult-Gerontology population are educated and certified across both areas of practice and will be titled Adult-Gerontology CNP or CNS. In addition, all APRNs in any of the four roles providing care to the adult population (e.g. Family or Gender Specific) must be prepared to meet the growing needs of the older adult population. Therefore the education program should include didactic and clinical education experiences necessary to prepare APRNs with these enhanced skills and knowledge.†The clinical nurse specialist (CNS) is educated and assessed through national certification processes across the continuum from wellness through acute care.‡The certified nurse practitioner (CNP) is prepared with the acute care CNP competencies and/or the primary care CNP competencies. At this point in time the acute care and primary care CNP delineation applies only to the Pediatrics and Adult-Gerontology CNP population foci. Scope of practice of the primary care or acute care CNP is not setting-specific but is based on patient care needs. Programs may prepare individuals across both the primary care and acute care CNP roles. If programs prepare graduates across both roles, the graduate must be prepared with the consensus-based competencies for both roles and must successfully obtain certification in both the acute and the primary care CNP roles. • Completes an accredited graduate-level education program preparing him or her for one of the four recognized APRN roles and a population focus (see discussion in Chapter 3) • Passes a national certification examination that measures APRN role and population-focused competencies and maintains continued competence by national recertification in the role and population focus • Possesses advanced clinical knowledge and skills preparing him or her to provide direct care to patients; the defining factor for all APRNs is that a significant component of the education and practice focuses on direct care of individuals • Builds on the competencies of RNs by demonstrating greater depth and breadth of knowledge and greater synthesis of data by performing more complex skills and interventions and by possessing greater role autonomy • Is educationally prepared to assume responsibility and accountability for health promotion and/or maintenance, as well as the assessment, diagnosis, and management of patient problems, including the use and prescription of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions • Has sufficient depth and breadth of clinical experience to reflect the intended license • Obtains a license to practice as an APRN in one of the four APRN roles The Consensus Model asserts that licensure must be based on educational preparation for one of the four existing APN roles and a population focus; certification must be within the same area of study; and that the four separate processes of LACE are necessary for the adequate regulation of APRNs (APRN Consensus Model, 2008; see Chapter 21). The six population foci displayed in Figure 2-1 include the individual and family across the life span, including adult, gerontologic, neonatal, pediatric, women’s health/gender-specific, and psychiatric and mental health populations. Preparation in a specialty, such as oncology or critical care, cannot be the basis for licensure. Specialization “indicates that an APRN has additional knowledge and expertise in a more discrete area of specialty practice. Competency in the specialty area could be acquired either by educational preparation or experience and assessed in a variety of ways through professional credentialing mechanisms (e.g., portfolios, examinations)” (APRN Consensus Model, 2008, p. 12). This was a critical decision for the group to reach, given the numbers of specialties and APN specialty examinations in place when the document was prepared. What are the limits of this conceptualization of advanced practice nursing? First, competencies that are common across APN roles are not addressed beyond defining an APRN and indicating that students must be prepared “with the core competencies for one of the four APRN roles across at least one of the six population foci” (APRN Consensus Model, 2008). However, as the Hamric Model suggests (see Chapter 3), there are core competencies that all APNs should possess. In addressing specialization, the model also leaves open the issue of the importance of educational preparation, in addition to experience, for advanced practice in a specialty. Experience in an area is certainly a factor that leads to the emergence of new specialties, but will experience alone be sufficient for the APN who specializes in oncology or critical care (or another specialty) to achieve desired outcomes in timely and cost-effective ways? These are specialties in which the population’s needs are many and complex and the scope of research knowledge is similarly broad and deep. These are important conceptualization questions that are probably best addressed by the ANA and specialty professional nursing organizations, rather than by a group with a regulatory focus. Numerous efforts are underway to implement this model in the United States; NCSBN has an extensive toolkit to help educators, APNs, consumers, and policymakers implement the new APRN regulatory model (NCSBN, 2012; https://www.ncsbn.org/2276.htm). The work undertaken to produce the APRN Consensus Model (2008) illustrates the power of interorganizational collaboration and is a promising example of how a model can, as Fawcett (2005) has suggested, reduce conflicts and facilitate communication within the profession, across professions, and with the public. As the “only full-service professional organization representing the interests of the nation’s 3.1 million registered nurses through its constituent and state nurses associations and its organizational affiliates,” the American Nurses Association (ANA) and its constituent organizations have also been active in developing and promulgating documents that address advanced practice nursing. Two of these are particularly important as we consider contemporary conceptualizations of advanced practice nursing. Since 1980, ANA has periodically updated its Social Policy Statement (ANA, 2010a). Specialization, expansion, and advancement have consistently been identified as concepts that can differentiate advanced practice nursing from basic nursing practice. The most recent edition notes that specialization (“focusing on a part of the whole field of professional nursing”) can occur at basic or advanced levels and that APNs use expanded and specialized knowledge and skills in their practices. According to the 2010 statement, expansion, specialization, and advanced practice were defined as follows (ANA, 2010a): ANA’s definitions of specialization and advanced practice are consistent with the APRN Consensus Model. ANA also establishes and promulgates standards of practice and competencies for RNs and APNs. In the second edition of their text, Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (ANA, 2010b), six standards of practice and 16 standards of professional performance are described. Of the 22 standards, one standard outlines additional expectations for APNs compared with RNs; Standard 5, “Implementation,” addresses the consultation and prescribing responsibilities of APRNs. Each standard is associated with competencies. It is in the description of the competencies that RN practice is differentiated from APNs and nurses prepared in a specialty at the graduate level. This document is must reading for APN students, practitioners, and others wishing to understand how basic, advanced, and specialized practice differ. In addition to these documents, ANA, together with the American Board of Nursing Specialties (ABNS), convened a task force on CNS competencies. For many reasons, including the recognition that developing psychometrically sound certifications for numerous specialties, especially for clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), would be difficult as the profession moved toward implementing the APRN Consensus Model, the ANA and ABNS convened a group of stakeholders in 2006 to develop and validate a set of core competencies that would be expected of CNSs entering practice (National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists [NACNS]/National CNS Core Competency Task Force, 2010). This group was charged with identifying core, entry-level competencies that are common in CNS practice, regardless of specialty. This work is discussed later in this chapter in the section on NACNS. Over the last decade, the AACN has undertaken two nursing education initiatives aimed at transforming nursing education. In 2006, AACN called for all APN preparation to take place at the doctoral level in practice-based programs (DNP), with master’s level education being refocused on generalist preparation for roles such as clinical nurse leaders (CNLs) and staff and clinical educators. CNLs are not APNs (AACN, 2005, 2012a; Spross, Hamric, Hall, et al., 2004) and, therefore, are not included in this discussion of conceptualizations. Through these initiatives, and to the extent that the AACN and Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) influence accreditation, the DNP may become the preferred degree for most APNs, although this goal is controversial. Since the last edition, despite lingering disagreements, DNP education has advanced considerably. In 2006, there were 20 DNP programs; in 2011, there were 182. Similarly, enrollments in and graduation from DNP programs have also risen substantially (AACN, 2012). The DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006) are comprised of eight competencies for DNP graduates (Box 2-2). Graduates are expected to demonstrate the eight essentials on graduation. For APNs, “Essential VIII specifies the foundational practice competencies that cut across specialties and are seen as requisite for DNP practice” (AACN, 2006, p. 16; Box 2-3). Recognizing that DNP programs will prepare nurses for roles other than APN roles, the AACN acknowledged that organizations representing APNs are expected to develop Essential VIII as it relates to specific advanced practice roles and “to develop competency expectations that build upon and complement DNP Essentials 1 through 8” (AACN, 2006, p. 17). These Essentials affirmed that the advanced practice nursing core includes the three Ps (three separate courses)—advanced health and physical assessment, advanced physiology and pathophysiology, and advanced pharmacology—and is specific to APNs. The specialty core must include content and clinical practice experiences that help students acquire the knowledge and skills essential to a specific advanced practice role. These requirements were reconfirmed in the Consensus Model (2008). The DNP has been described as a “disruptive innovation” (Hathaway, Jacob, Stegbauer, et al., 2006) and a natural evolution for NP practice. Although the DNP remains controversial (Avery & Howe, 2007; American College of Nurse-Midwives [ACNM], 2012b; Dreher & Smith Glasgow, 2011; Irvin-Lazorko, 2011; NACNS, 2009a), the proposal to make the DNP required for entry into advanced practice nursing is one of several national initiatives that have contributed to a broader discussion and may lead the profession to a clearer definition of advanced practice nursing. One outcome of the national DNP discussion is that APN organizations have promulgated practice competencies for doctorally prepared APNs (e.g., ACNM, 2011c; NACNS, 2009b) or have proposed a practice doctorate, even though it may not be the DNP (AANA, 2007). The National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (2012) now has one set of core competencies for NPs. Organizational positions on doctoral education are briefly explored in the discussion of APN organizations (see later). Readers can consult Chapters 14 through 18 and are urged to visit stakeholder organizations’ websites for the history and up to date information on organizational responses to AACN’s DNP position paper (AACN, 2004) and the DNP Essentials (AACN, 2006). Although not a conceptual model per se, the AACN’s publication, DNP Essentials (2006) addresses concepts and content that are now evident in many other documents that address standards of APN practice and education. The fact that Essential VIII affirms a set of common competencies across APN roles is an important contribution to conceptual clarity about advanced practice in the United States. Because these Essentials, with the exception of Essential VIII, are intended to address DNP preparation for any nursing role, its contribution to conceptual clarity regarding advanced practice nursing specifically is limited. Eventually, the evolution of the DNP may lead to more conceptual clarity about advanced practice nursing and the role of APNs. However, it is possible that the rapid expansion of this degree may contribute to less clarity in the short term about the nature of advanced nursing practice and the centrality of direct care of patients to APN work, particularly because the DNP will prepare people for other, nonclinical nursing roles. In the next section, in addition to discussing the organizations‘ conceptualizations of APN practice, the extent to which their responses to the DNP proposal might influence conceptual clarity on advanced nursing practice is addressed.

Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing

Application or testing of grand and middle-range theories to APN practice (e.g., Musker, 2011; Newcomb, 2010);

Application or testing of grand and middle-range theories to APN practice (e.g., Musker, 2011; Newcomb, 2010);

Models of role implementation (Ball & Cox, 2004; Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Browne, & Pinelli, 2004) and APN care delivery (Mahler, 2010; McAiney, Haughton, Jennings, et al., 2008; Dunphy & Winland-Brown, 1998; Dunphy, Winland-Brown, Porter, Thomas, & Gallagher, 2011; Curley, 1998; American Association of Critical Care Nurses, 2012)

Models of role implementation (Ball & Cox, 2004; Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Browne, & Pinelli, 2004) and APN care delivery (Mahler, 2010; McAiney, Haughton, Jennings, et al., 2008; Dunphy & Winland-Brown, 1998; Dunphy, Winland-Brown, Porter, Thomas, & Gallagher, 2011; Curley, 1998; American Association of Critical Care Nurses, 2012)

Nature, Purposes, and Components of Conceptual Models

Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing: Problems and Imperatives

Conceptualizations of Advanced Practice Nursing Roles: Organizational Perspectives

Consensus Model for Advanced Practice Registered Nurse Regulation

American Nurses Association

American Association of Colleges of Nursing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access