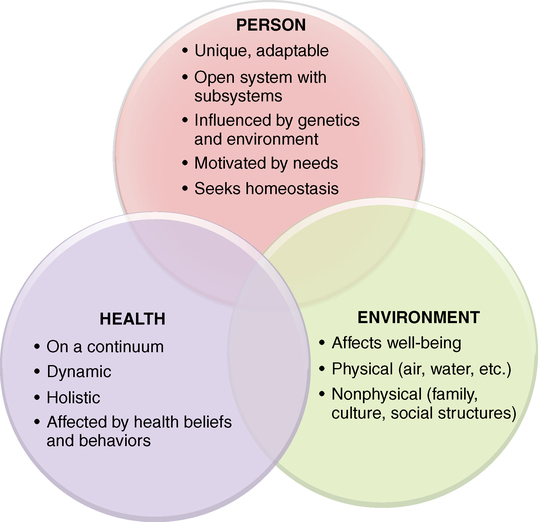

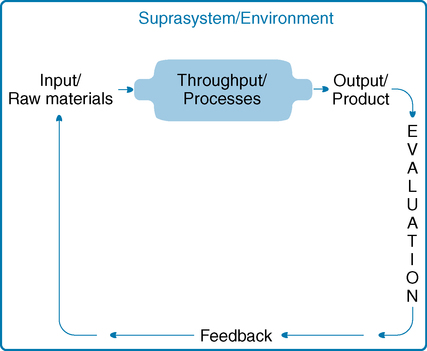

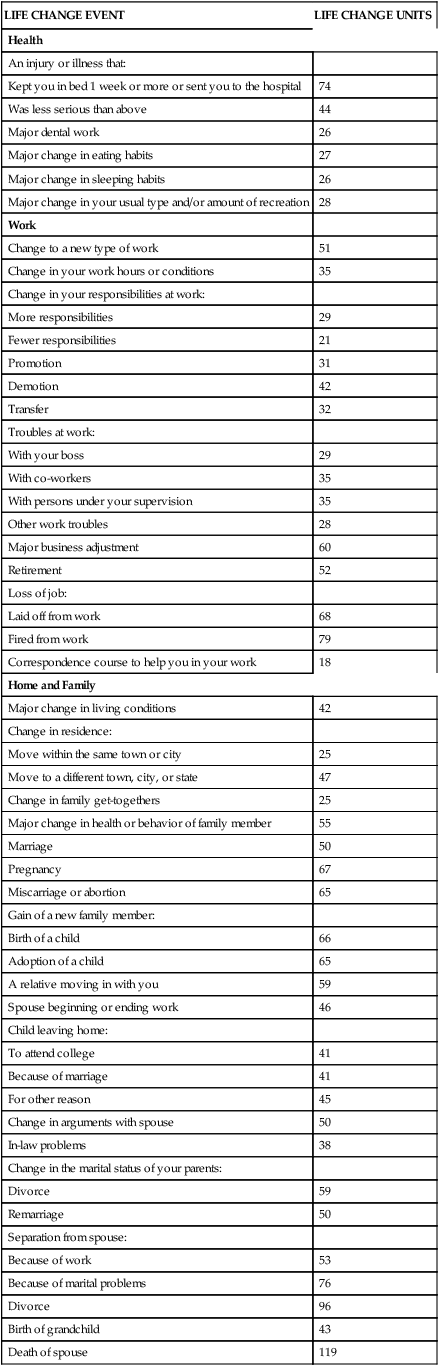

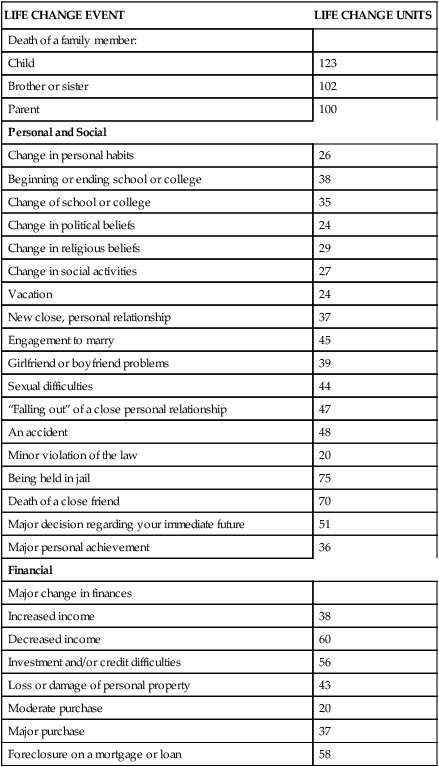

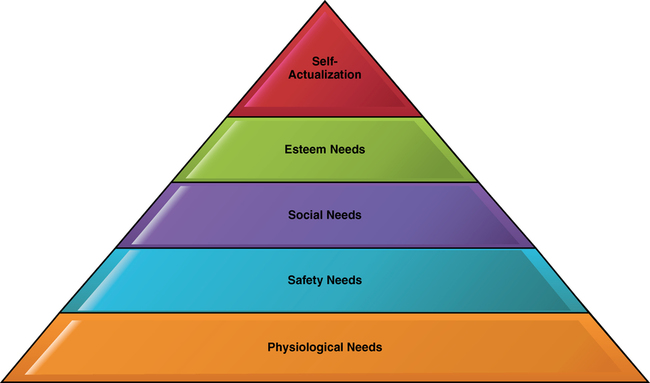

After studying this chapter, students will be able to: • Describe the components and processes of systems. • Explain Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs and its relationship to motivation. • Recognize how environmental factors such as family, culture, social support, the Internet, and community influence health. • Explain the significance of a holistic approach to nursing care. • Apply Rosenstock’s health belief model and Bandura’s theory of perceived self-efficacy to personal health behaviors and health behaviors of others. • Devise a personal plan for achieving high-level wellness. • Define and give examples of beliefs. • Define and give examples of values. • Cite examples of nursing philosophies. • Discuss the impact of beliefs and values on nurses’ professional behaviors. • Explain how nurses and organizations educating and employing nurses can use a philosophy of nursing. • Identify personal beliefs, values, and philosophies as they relate to nursing. To enhance your understanding of this chapter, try the Student Exercises on the Evolve site at http://evolve. elsevier.com/Black/professional. Chapter opening photo from istockphoto.com. The foundation of nursing—its bones—is its basic concepts, the ideas that are essential to understanding professional practice. These concepts are person, environment, and health. Each concept has subconcepts, which are other ideas that are related to the larger concept, but which are also related to nursing (Figure 12-1). Everything professional nurses do is in response to one of these basic interrelated concepts. You do not say, “I am going to check on Mrs. Bruce’s homeostasis.” But in fact when you check her fluid intake and urine output after her major surgery, you are addressing an element of her person (homeostasis—her fluid balance), her health (she is in a vulnerable state), and her environment (her intravenous line patency, her availability of water), in the context of nursing. You as a nurse are guided by beliefs, values, and a philosophy, which work in concert to shape your practice. An understanding of systems will guide you in understanding the connections and interactions among nursing’s basic concepts. A system is a set of interrelated parts that come together to form a whole that performs a function (von Bertalanffy, 1968). General systems theory was developed in 1936 by biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy, who believed that a common framework for studying several similar disciplines would allow scientists and scholars to organize and communicate findings, making it easier to build on the work of others. Each part of a system is a necessary or integral component required to make a complete, meaningful whole. These parts are input, throughput, output, evaluation, and feedback (von Bertalanffy, 1968). Feedback, the final component of a system, is the process of communicating what is found in evaluation of the system. Feedback is the information given back into the system to determine whether the purpose, or end result, of the system has been achieved. Figure 12-2 depicts the components of systems and illustrates how they relate to one another. At the individual patient level, the openness of human systems makes nursing intervention possible. Understanding systems helps nurses assess relationships among all the factors that affect patients, including the influence of nurses themselves. Nurses who understand systems view patients holistically, including the physiological subsystems (such as metabolism and the respiratory system) and suprasystem (such as family, culture, and community). These nurses appreciate the influence of change in any part of the system. For instance, when a patient with diabetes has pneumonia (change in subsystem), the infection increases the blood glucose level (metabolic system) and may result in hospitalization. Hospitalization may in turn adversely affect the patient’s role in the family and community (change in suprasystem). Key concepts of systems are summarized in Box 12-1. With this brief introduction to systems as a foundation, we can now examine the three basic concepts that are fundamental to the practice of professional nursing. In addition to having unique personal characteristics, people have inborn needs. A human need is something that is required for a person’s well-being. In 1954, psychologist Abraham Maslow published Motivation and Personality. In this classic book, Maslow rejected earlier ideas of Freud, who believed that people are motivated by unconscious instincts, and Pavlov, who believed humans were driven by conditioned reflexes. Instead, Maslow presented his human needs theory and explained that human behavior is motivated by intrinsic needs. He identified five levels of needs and organized them into a hierarchical order, as shown in Figure 12-3. Self-actualization is the highest level of needs. Self-actualized people have realized their maximum potential; they use their talents, skills, and abilities to the fullest extent possible and are true to their own nature. People do not stay in a state of self-actualization but may have “peak experiences” during which they realize self-actualization for some period of time. Maslow believed that many people strive for self-actualization, but few consistently reach that level (Maslow, 1987). He also believed that people are “innately motivated toward psychological growth, self-awareness, and personal freedom. As he saw it, we never outgrow the innate need for self-expression and self-development, no matter how old we are” (Hoffman, 2008, p. 36). Another aspect of human needs that must be considered is the nature of people to change, grow, and develop. Carl Rogers, a well-known psychologist, built his theory of personhood based on the idea that people are constantly adapting, discovering, and rediscovering themselves. His book On Becoming a Person (Rogers, 1961) is considered a classic in psychological literature. Rogers’ idea that a person’s needs change as the person changes is important for nurses to remember. The human potential to grow and develop can be used by nurses to assist patients to change unhealthy behaviors and to reach the highest level of wellness possible. The concept of adaptation is also helpful in understanding that people admitted to hospitals and removed from their customary, familiar environments commonly become anxious. Even the most confident person can become fearful when in an uncertain, perhaps threatening, situation. Under these circumstances, nurses have learned to expect people to regress slightly and to become more concerned with basic needs and less focused on the higher needs in Maslow’s hierarchy. A “take-charge” professional person, for example, may become somewhat demanding and self-absorbed when hospitalized. As you will see in Chapter 13, several nursing theorists based their theoretical models on adaptation. Individuals, as open systems, also endeavor to maintain balance between external and internal forces. When that balance is achieved, the person is healthy, or at least is resistant to disease. When environmental factors affect the homeostasis of a person, the person attempts to adapt to the change. If adaptation is unsuccessful, disequilibrium may occur, setting the stage for the development of illness or disease. How individuals respond to stress is a major factor in the development of illness. Stress and illness are discussed more fully in Chapter 10, and you may wish to review that information now. According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, more than 11% of people living in the United States are foreign born, a number that has stabilized in the past 5 years (2010). The United States has become a multicultural society. Because basic beliefs about health and illness vary widely from culture to culture, nurses need to develop cultural competence to meet the needs of culturally diverse patients. For example, many Mexican-American and Mexican immigrant families observe 40 days of recovery in the postpartum period—la cuarentena (cuarenta dias or quarantine)—when traditional behaviors related to diet, clothing, sexual abstinence, bathing, and management of the environment are practiced, and social support is intense. This culturally entrenched practice is misunderstood and even trivialized by providers, leading women to conceal their traditions (Waugh, 2010). Understanding the relationship between culture and health is the basis for “transcultural nursing,” a field of nursing practice initiated by nurse-anthropologist Madeleine Leininger. Additional discussion of the influence of culture on nursing practice can be found in Chapter 10. Holmes and Rahe (1967) published a study of the relationship of social change to the subsequent development of illness. They found that people with many social changes that disrupt social support, such as death of a loved one, divorce, job changes, moving, or unemployment, were much more likely to experience illness in the following 12 months than people with few social changes. Both positive and negative changes created the need for social readjustment. In 1995, this study was updated, and the Recent Life Changes Questionnaire (Box 12-2) was devised to reflect more accurately contemporary concerns (Miller and Rahe, 1997). Numerous other researchers have found additional evidence that social support has a direct relationship to health.

Conceptual and philosophical bases of nursing

Systems

Components of systems

Application of the systems model to nursing

Person

Human needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Adaptation and human needs

Homeostasis

Environment and suprasystem

Cultural systems

Social systems

Social change

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Conceptual and philosophical bases of nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access