Chapter 1 Concepts of health

Defining health, disease, illness and ill health

Health

Health is a broad concept which can embody a huge range of meanings, from the narrowly technical to the all-embracing moral or philosophical. The word ‘health’ is derived from the Old English word for heal (hael) which means ‘whole’, signalling that health concerns the whole person and his or her integrity, soundness or well-being. There are ‘common-sense’ views of health which are passed through generations as part of a common cultural heritage. These are termed ‘lay’ concepts of health, and everyone acquires a knowledge of them through their socialization into society. Different societies or different groups within one society have different views on what constitutes their ‘common sense’ about health.

Health has two common meanings in everyday use, one negative and one positive. The negative definition of health is the absence of disease or illness. This is the meaning of health within the western scientific medical model, which is explored in greater detail later on in this chapter. The positive definition of health is a state of well-being, interpreted by the World Health Organization in its constitution as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Organization 1946).

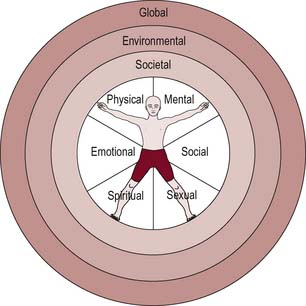

Health is holistic and includes different dimensions, each of which needs to be considered. Holistic health means taking account of the separate influences and interaction of these dimensions. Figure 1.1 shows a diagrammatic representation of the dimensions of health.

The inner circle represents individual dimensions of health.

The three outer circles are broader dimensions of health which affect the individual. Societal health refers to the link between health and the way a society is structured. This includes the basic infrastructure necessary for health (for example, shelter, peace, food, income), and the degree of integration or division within society. We shall see in Chapter 2 how the existence of patterned inequalities between groups of people harms health. Environmental health refers to the physical environment in which people live, and the importance of good-quality housing, transport, sanitation and pure water facilities and involves caring for the planet and ensuring its sustainability for the future.

Disease, illness and ill health

Social scientists view health and disease as socially constructed entities. Health and disease are not states of objective reality waiting to be uncovered and investigated by scientific medicine. Rather, they are actively produced and negotiated by ordinary people. In Cornwell’s (1984) study of London’s Eastenders, they referred to three categories of health problems:

Illness has often been conceptualized as deviance – as different from the norm and a source of stigma. Goffman (1968) identifies three sources of stigma:

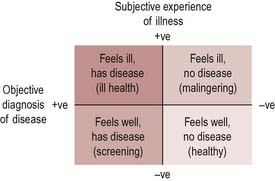

The subjective experience of feeling ill is not always matched by an objective diagnosis of disease. When this happens, doctors and health workers may label such sufferers ‘malingerers’, denying the validity of subjective illness. This can have important consequences, for example a sick certificate may be withheld if a doctor is not convinced that someone’s reported illness is genuine. The acceptance of a behaviour as an illness then becomes an issue of how to manage it. Several conditions, such as chronic fatigue syndrome and repetitive strain injury (RSI), have taken a long time to be recognized as illnesses.

Homosexuals, formerly considered to be sinners, were labelled as ill – not bad but mad. Commitments to mental institutions, hormonal treatments, and castrations were used to deal with unwanted sexual behaviour…. treatments for homosexual men – such as aversion therapy – continued until, and beyond, 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association redesigned homosexuality as non-pathological (Hart & Wellings 2002).

It is also possible to experience no symptoms or signs of disease, but to be labelled sick as a result of examination or screening. Hypertension and precancerous changes to cell structures are two examples where screening may identify a disease even though the person concerned may feel perfectly healthy. Figure 1.2 gives a visual representation of these discrepancies. The central point is that subjective perceptions cannot be overruled, or invalidated, by scientific medicine.

The western scientific medical model of health

The scientific medical model arose in western Europe at the time of the Enlightenment, with the rise of rationality and science as forms of knowledge. In earlier times, religion provided a way of knowing and understanding the world. The Enlightenment changed the old order, and substituted science for religion as the dominant means of knowledge and understanding. This was accompanied by a proliferation of equipment and techniques for studying the world. The invention of the microscope and telescope revealed whole worlds which had previously been invisible. Observation, calculation and classification became the means of increasing knowledge. Such knowledge was put to practical purposes, and applied science was one of the forces which accompanied the Industrial Revolution. In an atmosphere when everything was deemed knowable through the proper application of scientific method, the human body became a key object for the pursuit of scientific knowledge. What could be seen, and measured, and catalogued, was ‘true’ in an objective and universal sense.

This view of health is characterized as:

The pathogenic focus on finding the causes for ill health has led to an emphasis on risk factors. Antonovsky (1993) has called for a salutogenic approach which looks instead at why some people remain healthy. He identifies coping mechanisms which enable some people to remain healthy despite adverse circumstances, change and stress. An important factor for health, which Antonovsky labels a ‘sense of coherence’, involves the three aspects of understanding, managing and making sense of change. These are human abilities which are in turn nurtured or obstructed by the wider environment.

Table 1.1 contrasts the traditional views of a medical model with that of a social model of health.

Table 1.1 The medical and social model of health

| Medical model | Social model |

|---|---|

| Health is the absence of disease | Health is a product of social, biological and environmental factors |

| Health services are geared towards treating the sick and disabled | Services emphasize all stages of prevention and treatment |

| High value is placed on specialist medical services | Less emphasis is placed on the role of specialists – there is more attention to self-help and community activity |

| Health workers diagnose and treat and sanction ‘the sick role’ | Health workers enable people to take greater control over their own health |

| The pathogenic focus emphasizes finding biological cause | A salutogenic focus emphasizes understanding why people are healthy |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

BOX 1.1

BOX 1.1

BOX 1.2

BOX 1.2 BOX 1.3

BOX 1.3

BOX 1.4

BOX 1.4