Linda Laskowski-Jones and Karen L. Toulson

Concepts of Emergency and Trauma Nursing

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

2 Identify the roles and responsibilities of the health care team members in the ED.

3 Plan and implement best practices to maintain staff and patient safety in the ED.

4 Explain selected core competencies that nurses need to function in the ED.

5 Triage patients in the ED to prioritize the order of care delivery.

6 Prioritize resuscitation interventions based on the primary survey of the injured patient.

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

8 Describe the general process of admission through disposition of a patient in the ED.

9 Prevent or reduce common risk factors in the ED that contribute to adverse events in older adults.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The demand for emergency care in the United States is growing rapidly. Emergency departments (EDs) function as safety nets for communities of all sizes by providing services to both insured and uninsured patients seeking medical care. They are also responsible for public health surveillance and emergency disaster preparedness. Some hospital-based emergency departments also provide observation, procedural care, and employee health services (Moskop et al., 2009). The role of the ED is so vital that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2010) has a process for designating small rural facilities of 25 inpatient beds or fewer as critical access hospitals if they provide around-the-clock emergency care services 7 days per week. Critical access hospitals are considered necessary providers of health care to community residents that are not close to other hospitals in a given region.

Because of the multi-specialty nature of the environment, EDs play a unique role within the U.S. health care system. More than 119 million people visit the ED each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2010). The demand for emergency care has greatly increased over the past 15 years, and the health care consumer has higher expectations; however, the capacity to provide necessary resources has not kept pace in most systems. Emergency department crowding occurs when the need for care exceeds available resources in the department, hospital, or both (Howard, 2009).

The Emergency Department Environment of Care

In the emergency care environment, rapid change is the rule. The typical ED is fast paced and, at the height of activity, might even appear chaotic. Patients seek treatment for a number of physical, psychological, spiritual, and social reasons. In general, nurses work in this environment because they dislike routines and thrive in challenging, stimulating work settings. Although most EDs have treatment areas that are designated for certain populations such as patients with trauma or cardiac, psychiatric, or gynecologic problems, care can actually take place almost anywhere. In a crowded ED, patients may receive initial treatment outside of the usual treatment rooms, including the waiting room and hallways.

The ED is typically alive with activity and noise, although the pace decreases at times because arrivals are random. Emergency nurses can expect background sounds that include ringing telephones, monitor alarms, vocal patients, crying children, and radio transmissions between staff and incoming ambulance or helicopter personnel. Interruptions are the norm.

Demographic Data

Staff members in the ED provide care for people across the life span with a broad spectrum of issues, illnesses, and injuries—as well as various cultural and religious values. Especially vulnerable populations who visit the ED include the homeless, the poor, and older adults. During a given shift, for example, the emergency nurse may function as a cardiac nurse, a geriatric nurse, a psychiatric nurse, and a trauma nurse. Patient acuity runs the range from life-threatening emergencies to minor symptoms that could be addressed in a primary care office or community clinic. Some of the most common reasons that people seek ED care are:

Special Nursing Teams

Many EDs have specialized teams that deal with high-risk populations of patients. One example is the forensic nurse examiner team. Forensic nurse examiners (RN-FNEs) are educated to obtain patient histories, collect forensic evidence, and offer counseling and follow-up care for victims of rape, child abuse, and domestic violence—also known as intimate partner violence (IPV) (Scales et al., 2007). They are trained to recognize evidence of abuse and to intervene on the patient’s behalf. Forensic nurses who specialize in helping victims of sexual assault are called sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) or sexual assault forensic examiners (SAFEs).

Interventions performed by forensic nurses may include providing information about developing a safety plan or how to escape a violent relationship. Forensic nurse examiners document injuries and collect physical and photographic evidence. They may also provide testimony in court as to what was observed during the examination and information about the type of care provided.

The psychiatric crisis nurse team is another example of an ED specialty team. Many patients who visit the ED for their acute problems also have chronic mental health disorders. The availability of mental health nurses can improve the quality of care delivered to these patients who require specialized interventions in the ED and can offer valuable expertise to the emergency health care staff. For example, the team evaluates patients with emotional behaviors or mental illness and facilitates the follow-up treatment plan, including possible admission to an appropriate psychiatric facility. These nurses also interact with patients and families when sudden illness, serious injury, or death of a loved one may have caused a crisis. On-site interventions can help patients and families cope with these unexpected changes in their lives.

Interdisciplinary Team Collaboration

The emergency nurse is one member of the large interdisciplinary team who provides care for patients in the ED. A collaborative team approach to emergency care is considered a standard of practice. In this setting, the nurse coordinates care with all levels of health care team providers, from prehospital emergency medical services (EMS) personnel to physicians, hospital technicians, and professional and ancillary staff.

Prehospital Care Providers

Prehospital care providers are typically the first caregivers that patients see before transport to the ED by an ambulance or helicopter (Fig. 10-1). Local protocols define the skill level of the EMS responders dispatched to provide assistance. Emergency medical technicians (EMTs) offer basic life support (BLS) interventions such as oxygen, basic wound care, splinting, spinal immobilization, and monitoring of vital signs. Some units carry automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) and may be authorized to administer selected drugs such as an EpiPen or nitroglycerin based on established medical protocols. For patients who require care that exceeds BLS resources, paramedics are usually dispatched. Paramedics are advanced life support (ALS) providers who can perform advanced techniques, which may include cardiac monitoring, advanced airway management and intubation, establishing IV access, and administering drugs en route to the ED (Fig. 10-2).

The prehospital provider is a key source for valuable patient data. Emergency nurses rely on these providers to be the “eyes and ears” of the health care team in the prehospital setting and to communicate this information to other staff members for continuity of care.

Physicians and Other Health Care Providers

Another integral member of the emergency health care team is the emergency medicine physician. These medical professionals receive specialized education and training in emergency patient management. In the past, physicians of all types of skills rotated through the ED. As emergency care became increasingly complex and specialized, emergency medicine became a recognized physician specialty practice, complete with board certification requirements.

The emergency nurse interacts with a number of staff and community physicians involved in patient care but works most closely with emergency medicine physicians. Even though other physician specialists may be involved in ED patient treatment, the emergency medicine physician typically directs the overall care in the department. Many EDs also employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to assume designated roles in patient assessment and treatment. Teaching hospitals also have resident physicians who train in the ED. They act in collaboration with or under the supervision of the emergency medicine physician to assist with emergency care delivery.

Support Staff

The emergency nurse interacts on a regular basis with professional and ancillary staff who function in support roles. These personnel include radiology and ultrasound technicians, respiratory therapists, laboratory technicians, social workers, nursing assistants, and clerical staff. Each support staff member is essential to the success of the emergency health care team. The ED nurse is accountable for communicating pertinent staff considerations, patient needs, and restrictions to support staff (e.g., physical limitations, isolation precautions) to ensure that ongoing patient and staff safety issues are addressed. For example, the respiratory therapist can assist the nurse to troubleshoot mechanical ventilator issues. Laboratory technicians can offer advice regarding best practice techniques for specimen collection. During the discharge planning process, social workers or case managers can be tremendous patient advocates in locating community resources, including temporary housing, durable medical equipment (DME), drug and alcohol counseling, health insurance information, and prescription services.

Inpatient Unit Staff

The emergency nurse’s interactions extend beyond the walls of the ED. Communication with staff nurses from the inpatient units is necessary to ensure continuity of patient care. Providing a concise but comprehensive report of the patient’s ED experience is essential for the hand-off communication process and patient safety (Mascioli et al., 2009). Information should include the patient’s:

• Situation (reason for being in the ED)

• Assessment and diagnostic findings

• Transmission-based precautions needed

The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs) (2010) require hospitals and other health care agencies to use a standardized approach to hand-off communications to prevent errors that are caused by poor or inadequate communication. Many agencies use the SBAR method (situation, background, assessment, response) or some variation of that method to ensure complete and clearly understood communication. Chapter 1 discusses the SBAR technique in more detail.

Both emergency nurses and nurses on inpatient units need to understand the unique aspects of their two practice environments to prevent conflicts. For example, nurses on inpatient units may be critical of the push to move patients out of the ED setting quickly, particularly when the unit activity is high. Similarly, the emergency nurse may be critical of the inpatient unit’s lack of understanding or enthusiasm for accepting admissions rapidly. Effective interpersonal communication skills and respectful negotiation can optimize teamwork between the emergency nurse and the inpatient unit nurse. For instance, when ED patient volume or acuity is overwhelming, the unit nurse can volunteer to assist the ED nurse by moving a monitored patient to the hospital bed. The emergency nurse may decide to delay sending admitted patients to inpatient units during change of shift or crisis periods such as a cardiac arrest on the unit, whenever possible.

Staff and Patient Safety Considerations

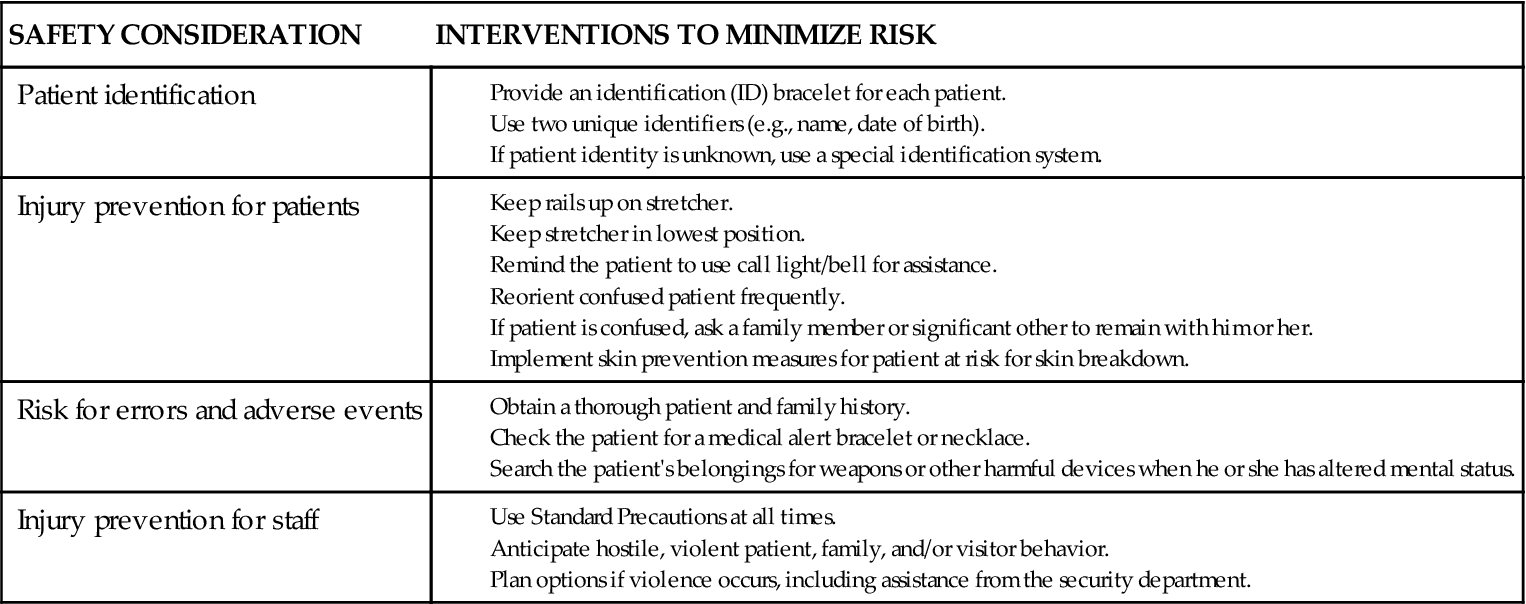

In the emergency department (ED) setting, staff and patient safety are major concerns (Chart 10-1). Staff safety concerns center on the potential for transmission of disease and on personal safety when dealing with aggressive, agitated, or violent patients and visitors.

Staff Safety

The emergency nurse uses Standard Precautions at all times when a potential for contamination by blood or other body fluids exists. Patients with tuberculosis or other airborne pathogens are preferentially placed in a negative pressure room if available. The nurse wears a powered air-purifying respirator (PAPR) or a specially fitted facemask before engaging in any close interaction with these patients. Hostile patient and visitor behaviors also pose injury risks to staff members.

Many EDs have at least one security guard present at all times for immediate assistance with these situations. Metal detectors may be used as a screening device for patients and visitors who are suspected of having weapons. Strategically located panic buttons and remote door access controls allow staff to get help and secure major ED or hospital entrances. The triage reception area—a particularly vulnerable access point into the ED—is often designed to serve as a security barrier with bullet-proof glass (Laskowski-Jones et al., 2005). Hospitals may even employ canine units made up of specially trained officers and dogs to patrol high-risk areas and respond to handle threatening situations (Johnson & Parker, 2009).

Patient Safety

In addition to concerns about staff safety, some of the most common patient safety issues are:

Hospital emergency departments have unique factors that can affect patient safety. These factors include the provision of complex emergency care, constant interruptions, and the need to interact with the many providers involved in caring for one patient.

Correct patient identification is critical in any health care setting. All patients are issued an identification bracelet at their point of entry of the ED—generally at the triage registration desk or at the bedside if emergent needs exist. For patients with an unknown identity and those with emergent conditions that prevent the proper identification process (e.g., unconscious patient without identification, emergent trauma patient), hospitals commonly use a “Jane/John Doe” or another identification system. Whatever method is used, always verify the patient’s identity using two unique identifiers before each intervention and before medication administration per The Joint Commission’s 2010 National Patient Safety Goals. Examples of appropriate identifiers include the patient’s birth date, agency identification number, home telephone number or address, and/or Social Security number.

Fall prevention starts with identifying people at risk for falls and then applying appropriate fall precautions. Patients can enter the ED without apparent fall risk factors, but because of interventions such as pain medication, sedation, or lower extremity cast application, for example, they can become a risk for falls. Falls can also occur in patients with medical conditions or drugs that cause syncope (“blackouts”). Many older adults also experience orthostatic (postural) hypotension as a side effect of cardiovascular drugs. In this case, patients become dizzy when changing from a lying or sitting position.

Some patients spend a lengthy time on stretchers while awaiting unit bed availability—possibly as long as 1 to 2 days in hospitals. During that time, basic health needs require attention, including providing nutrition, hygiene, and privacy for all ED patients. Waiting in the ED can cause increased pain in patients with back pain or arthritis.

Protecting skin integrity also begins in the ED. Emergency nurses need to assess the skin frequently and implement preventive interventions into the ED plan of care, especially when caring for older adults or those of any age who are immobilized. Interventions that promote clean, dry skin for incontinent patients, mobility techniques that decrease shearing forces when moving the immobile patient, and routine turning help prevent skin breakdown. Chapter 27 describes additional nursing interventions for preventing skin breakdown.

A significant risk for all patients who enter the emergency care environment is the potential for medical errors or adverse events, especially those associated with medication administration. The episodic and often chaotic nature of emergency management in an environment with frequent interruptions can easily lead to errors.

To reduce error potential, the emergency nurse makes every attempt to obtain essential and accurate medical history information from the patient, family, or reliable significant others as necessary. When dealing with patients who arrive with an altered mental status, a quick survey to determine whether the person is wearing a medical alert bracelet or necklace is important to gain medical information. In addition, a two-person search of patient belongings may yield medication containers; the name of a physician, pharmacy, or family contact person; or a medication list. In this case, the nurse serves as a detective to find clues, which may not only promote safety but also help determine the diagnosis and influence the overall emergency treatment plan. Automated electronic tracking systems are also available in some EDs to assist staff in identifying the location of patients at any given time and in monitoring the progress of care delivery during the visit. These valuable safety measures are especially important in large or busy EDs with a high population of older adults (Laskowski-Jones, 2008).

In addition to falls and pressure ulcer development, another adverse event that can result from a prolonged stay in the ED is a hospital-acquired infection. Older adults, in particular, are at risk for urinary tract or respiratory infections. Patients who are immune suppressed, especially those on chronic steroid therapy or immune modulators, are also at a high risk. Nurses and other ED personnel need to wash their hands frequently and thoroughly or use hand sanitizers to help prevent pathogen transmission.

Scope of Emergency Nursing Practice

The scope of emergency nursing practice encompasses management of patients across the life span—from birth through death—and all health conditions that prompt a person of any age to seek emergency care.

Core Competencies

Emergency nursing practice requires that nurses be skilled in patient assessment, priority setting and clinical decision making, multitasking, and communication. A sound knowledge base is also essential. Flexibility and adaptability are vital traits because situations within the ED, as well as individual patients, can change rapidly.

Like that of any nurse in practice, the foundation of the emergency nurse’s skill base is assessment. He or she must be able to rapidly and accurately interpret assessment findings according to acuity and age. For example, mottling of the extremities may be a normal finding in a newborn but it may indicate poor peripheral perfusion and a shock state in an adult.

Another skill for the emergency nurse is priority setting, which is essential in the triage process and is described on p. 127. Priority setting depends on accurate assessment, as well as good critical thinking and clinical decision-making skills. These skills are generally gained through hands-on clinical experience in the ED. However, discussion of case studies and the use of human patient simulation and simulation software can help prepare nurses to acquire this skill base in a nonthreatening environment and then apply it in the actual clinical situation (Wolf, 2008).

The knowledge base for emergency nurses is broad and ranges from critical care emergencies to less common problems, such as snakebites and hazardous materials contamination (see Chapters 11 and 12). ED nurses also learn to recognize and manage the legal implications of societal problems such as domestic violence, elder abuse, and sexual assault.

Although most EDs have physicians available around the clock who are physically located within the ED, the nurse often initiates interdisciplinary protocols for lifesaving interventions such as cardiac monitoring, oxygen therapy, insertion of IV catheters, and infusion of appropriate parenteral solutions. In many EDs, nurses function under clearly defined medical protocols that allow them to initiate drug therapy for emergent conditions such as anaphylactic shock and cardiac arrest. Emergency care principles extend to knowing what essential laboratory and diagnostic tests may be needed and, when necessary, obtaining them.

The emergency nurse must also be proficient in performing a variety of technical skills (multitasking), sometimes in a stressful, high-pressure environment such as a cardiac or trauma resuscitation. In addition to basic skills, he or she may also need to be proficient with critical care equipment, such as invasive pressure monitoring devices and mechanical ventilators. This type of equipment is commonly found in EDs that are part of Levels I and II trauma centers.

The nurse also assists the physician with a number of procedures. Knowledge and skills related to procedural setup, patient preparation, teaching, and postprocedure care are key aspects of emergency nursing practice. Common ED procedures include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree