Conception Through Adolescence

Objectives

• Describe characteristics of physical growth of the unborn child and from birth to adolescence.

• Describe cognitive and psychosocial development from birth to adolescence.

• Explain the role of play in the development of a child.

• Discuss ways in which the nurse is able to help parents meet their children’s developmental needs.

Key Terms

Adolescence, p. 151

Apgar score, p. 140

Attachment, p. 140

Embryo, p. 139

Embryonic stage, p. 139

Estrogen, p. 151

Fetal stage, p. 139

Fetus, p. 140

Fontanels, p. 141

Inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs), p. 142

Infancy, p. 143

Menarche, p. 152

Molding, p. 141

Neonatal period, p. 141

Placenta, p. 140

Preembryonic stage, p. 139

Preschool period, p. 147

Puberty, p. 151

School-age, p. 149

Sexually transmitted infection (STI), p. 151

Testosterone, p. 151

Toddlerhood, p. 146

![]()

Stages of Growth and Development

Human growth and development are continuous and complex processes that are typically divided into stages organized by age-groups such as from conception to adolescence. Although this chronological division is arbitrary, it is based on the timing and sequence of developmental tasks that the child must accomplish to progress to another stage. This chapter focuses on the various physical, psychosocial, and cognitive changes and health risks and health promotion concerns during the different stages of growth and development.

Selecting a Developmental Framework for Nursing

Providing developmentally appropriate nursing care is easier when you base planning on a theoretical framework (see Chapter 11). An organized, systematic approach ensures that the plan of care assesses and meets the child’s and family’s needs. If you deliver nursing care only as a series of isolated actions, you will possibly overlook some of the child’s developmental needs. A developmental approach encourages organized care directed at the child’s current level of functioning to motivate self-direction and health promotion. For example, nurses encourage toddlers to feed themselves to advance their developing independence and thus promote their sense of autonomy. Another example involves a nurse understanding an adolescent’s need to be independent and thus establishing a contract about the care plan and its implementation.

Intrauterine Life

From the moment of conception until birth, human development proceeds at a predictive and rapid rate. During gestation or the prenatal period, the embryo grows from a single cell to a complex, physiological being. All major organ systems develop in utero, with some functioning before birth. Development proceeds in a cephalocaudal (head-to-toe) and proximal-distal (central-to-peripheral) pattern (Santrock, 2009).

Pregnancy that reaches full term is calculated to last an average of 38 to 40 weeks and is divided into three stages or trimesters. Beginning on the day of fertilization, the first 14 days are referred to as the preembryonic stage, followed by the embryonic stage that lasts from day 15 until the eighth week. These two stages are then followed by the fetal stage that lasts from the end of the eighth week until birth (Davidson et al., 2008). Gestation is commonly divided into equal phases of 3 months called trimesters.

The placenta begins development at the third week of the embryonic stage and produces essential hormones that help maintain the pregnancy. It functions as the fetal lungs, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and an endocrine organ. Because the placenta is extremely porous, noxious materials such as viruses, chemicals, and drugs also pass from mother to child. These agents are called teratogens and can cause abnormal development of structures in the embryo. The effect of teratogens on the fetus or unborn child depends on the developmental stage in which exposure takes place, individual genetic susceptibility, and the quantity of the exposure. The embryonic stage is the most vulnerable since all body organs are formed by the eighth week. Some maternal infections can cross the placental barrier and negatively influence the health of the mother, fetus, or both. It is important to educate women about avoidable sources of teratogens and help them make healthy lifestyle choices before and during pregnancy.

Health Promotion During Pregnancy

The diet of a woman both before and during pregnancy has a significant effect on fetal development. Women who do not consume adequate nutrients and calories during pregnancy may not be able to meet the fetus’ nutritional requirements. An increase in weight does not always indicate an increase in nutrients. In addition, the pattern of weight gain is important for tissue growth in a mother and fetus. For women who are at normal weight for height, the recommended weight gain is 25 to 35 pounds over three trimesters (Davidson et al., 2008). As a nurse, you are in a key position to provide women with the education they need about nutrition before conception and throughout an expectant mother’s pregnancy.

Pregnancy presents a developmental challenge that includes physiological, cognitive, and emotional states that are accompanied by stress and anxiety. The expectant woman will soon adopt a parenting role; and relationships within the family will change, whether or not there is a partner involved. Pregnancy can be a period of conflict or support; family dynamics impact fetal development. Parental reactions to pregnancy change throughout the gestational period, with most couples looking forward to the birth and addition of a new family member (Davidson et al., 2008). Listen carefully to concerns expressed by a mother and her partner and offer support through each trimester.

The age of the pregnant woman sometimes plays a role in the health of the fetus and the overall pregnancy. Fetuses of older mothers are at risk for chromosomal defects, and older women may have more difficulty in becoming pregnant (Santrock, 2009). Studies indicate that pregnant adolescents often seek out less prenatal care than women in their 20s and 30s and are at higher risk for complications of pregnancy and labor. Infants of teen mothers are at increased risk for prematurity; low birth weight; and exposure to alcohol, drugs, and tobacco in utero and early childhood (Davidson et al., 2008). Adolescents who have been able to participate in prenatal classes may have improved nutrition and healthier babies.

Fetal growth and hormonal changes during pregnancy often result in discomfort for the expectant mother. Common concerns expressed include problems such as nausea and vomiting, breast tenderness, urinary frequency, heartburn, constipation, ankle edema, and backache. Always anticipate these discomforts and provide self-care education throughout the pregnancy. Discussing the physiological causes of these discomforts and offering suggestions for safe treatment can be very helpful for expectant mothers and contribute to overall health during pregnancy (Davidson et al., 2008).

Some complementary and alternative therapies such as herbal supplements can be harmful during pregnancy. Your assessment should include questions about use of these substances when providing education during pregnancy (Davidson et al., 2008). You can promote maternal and fetal health by providing accurate and complete information about health behaviors that support positive outcomes for pregnancy and childbirth.

Transition from Intrauterine to Extrauterine Life

The transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life requires profound physiological changes in the newborn and occurs during the first 24 hours of life. Assessment of the newborn during this period is essential to ensure that the transition is proceeding as expected. Gestational age and development, exposure to depressant drugs before or during labor, and the newborn’s own behavioral style also influence the adjustment to the external environment.

Physical Changes

An immediate assessment of the newborn’s condition to determine the physiological functioning of the major organ systems occurs at birth. The most widely used assessment tool is the Apgar score. Heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, reflex irritability, and color are rated to determine overall status of the newborn. The Apgar assessment is generally conducted at 1 and 5 minutes after birth and is sometimes repeated until the newborn’s condition stabilizes. The most extreme physiological change occurs when the newborn leaves the utero circulation and develops independent circulatory and respiratory functioning.

Nursing interventions at birth include maintaining an open airway, stabilizing and maintaining body temperature, and protecting the newborn from infection. The removal of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal secretions with suction or a bulb syringe ensures airway patency. Newborns are susceptible to heat loss and cold stress. Because hypothermia increases oxygen needs, it is essential to stabilize and maintain the newborn’s body temperature. Healthy newborns may be placed directly on the mother’s abdomen and covered in warm blankets or provided warmth via a radiant warmer. Preventing infection is a major concern in the care of the newborn, whose immune system is immature. Good handwashing technique is the most important factor in protecting the newborn from infection. You can help prevent infection by instructing parents and visitors to wash their hands before touching the infant.

Psychosocial Changes

After immediate physical evaluation and application of identification bracelets, the nurse promotes the parents’ and newborn’s need for close physical contact. Early parent-child interaction encourages parent-child attachment. Merely placing the family together does not promote closeness. Most healthy newborns are awake and alert for the first half-hour after birth. This is a good time for parent-child interaction to begin. Close body contact, often including breastfeeding, is a satisfying way for most families to start bonding. If immediate contact is not possible, incorporate it into the care plan as early as possible, which means bringing the newborn to an ill parent or bringing the parents to an ill or premature child. Attachment is a process that evolves over the infant’s first 24 months of life, and many psychologists believe that a secure attachment is an important foundation for psychological development in later life (Santrock, 2009).

Newborn

The neonatal period is the first 28 days of life. During this stage the newborn’s physical functioning is mostly reflexive, and stabilization of major organ systems is the primary task of the body. Behavior greatly influences interaction among the newborn, the environment, and caregivers. For example, the average 2-week-old smiles spontaneously and is able to look at the mother’s face. The impact of these reflexive behaviors is generally a surge of maternal feelings of love that prompt the mother to cuddle the baby. You apply knowledge of this stage of growth and development to promote newborn and parental health. For example, the newborn’s cry is generally a reflexive response to an unmet need (such as hunger, fatigue, or discomfort). Thus you help parents identify ways to meet these needs by counseling them to feed their baby on demand rather than on a rigid schedule.

Physical Changes

You perform a comprehensive nursing assessment as soon as the newborn’s physiological functioning is stable, generally within a few hours after birth. At this time the nurse measures height, weight, head and chest circumference, temperature, pulse, and respirations and observes general appearance, body functions, sensory capabilities, reflexes, and responsiveness. Following a comprehensive physical assessment, assess gestational age and interactions between infant and parent that indicate successful attachment (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

The average newborn is 2700 to 4000 g (6 to 9 pounds), 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 inches) in length, and has a head circumference of 33 to 35 cm (13 to 14 inches). Neonates lose up to 10% of birth weight in the first few days of life, primarily through fluid losses by respiration, urination, defecation, and low fluid intake. They usually regain birth weight by the second week of life; and a gradual pattern of increase in weight, height, and head circumference is evident. Accurate measurement as soon as possible after birth provides a baseline for future comparison (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

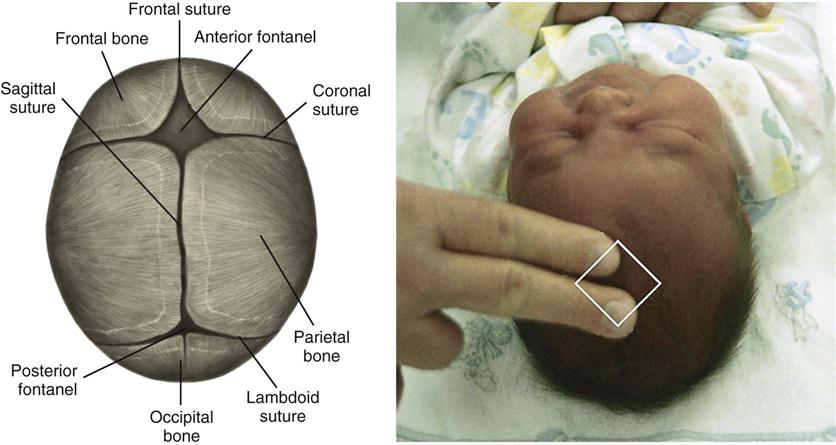

Normal physical characteristics include the continued presence of lanugo on the skin of the back; cyanosis of the hands and feet for the first 24 hours; and a soft, protuberant abdomen. Skin color varies according to racial and genetic heritage and gradually changes during infancy. Molding, or overlapping of the soft skull bones, allows the fetal head to adjust to various diameters of the maternal pelvis and is a common occurrence with vaginal births. The bones readjust within a few days, producing a rounded appearance to the head. The sutures and fontanels are usually palpable at birth. Fig. 12-1 shows the diamond shape of the anterior fontanel and the triangular shape of the posterior fontanel between the unfused bones of the skull. The anterior fontanel usually closes at 12 to 18 months, whereas the posterior fontanel closes by the end of the second or third month.

Assess neurological function by observing the newborn’s level of activity, alertness, irritability, and responsiveness to stimuli and the presence and strength of reflexes. Normal reflexes include blinking in response to bright lights, startling in response to sudden loud noises or movement, sucking, rooting, grasping, yawning, coughing, sneezing, palmar grasp, swallowing, plantar grasp, Babinski, and hiccoughing. Assessment of these reflexes is vital because the newborn depends largely on reflexes for survival and in response to its environment. Fig. 12-2 shows the tonic neck reflex in the newborn.

Normal behavioral characteristics of the newborn include periods of sucking, crying, sleeping, and activity. Movements are generally sporadic, but they are symmetrical and involve all four extremities. The relatively flexed fetal position of intrauterine life continues as the newborn attempts to maintain an enclosed, secure feeling. Newborns normally watch the caregiver’s face; have a nonpurposeful reflexive smile; and respond to sensory stimuli, particularly the primary caregiver’s face, voice, and touch.

In accordance with the recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), position infants for sleep on their backs to decrease the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011; Santrock, 2008). Newborns establish their individual sleep-activity cycle, and parents develop sensitivity to their baby’s cues. Studies have found that parents position their infants at home in the same positions they observed in the hospital setting; thus nurses must demonstrate correct positioning on the back to reduce the incidence of SIDS (Davidson et al., 2008). Co-sleeping or bed sharing has also been reported to possibly be associated with an increased risk for SIDS (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011; Santrock, 2008). Safeguards include proper positioning; removing stuffed animals, soft bedding, and pillows; and avoiding overheating the infant. Individuals should avoid smoking during pregnancy and around the infant because it places the infant at greater risk for SIDS (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Cognitive Changes

Early cognitive development begins with innate behavior, reflexes, and sensory functions. Newborns initiate reflex activities, learn behaviors, and learn their desires. At birth infants are able to focus on objects about 20 to 25 cm (8 to 10 inches) from their faces and perceive forms. A preference for the human face is apparent. Teach parents about the importance of providing sensory stimulation such as talking to their babies and holding them to see their faces. This allows infants to seek or take in stimuli, thereby enhancing learning and promoting cognitive development.

For newborns crying is a means of communication to provide cues to parents. Some babies cry because their diapers are wet or they are hungry or want to be held. Others cry just to make noise or because they need a change in position or activity. The crying frustrates the parents if they cannot see an apparent cause. With the nurse’s help parents learn to recognize infants’ cry patterns and take appropriate action when necessary.

Psychosocial Changes

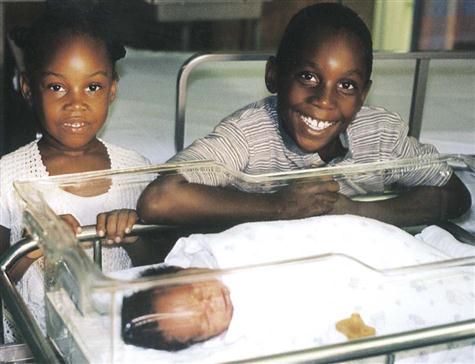

During the first month of life most parents and newborns normally develop a strong bond that grows into a deep attachment. Interactions during routine care enhance or detract from the attachment process. Feeding, hygiene, and comfort measures consume much of infants’ waking time. These interactive experiences provide a foundation for the formation of deep attachments. Early on older siblings need to have opportunity to be involved in the newborn’s care. Family involvement helps support growth and development and promotes nurturing (Fig. 12-3).

If parents or children experience health complications after birth, this may compromise the attachment process. Infants’ behavioral cues are sometimes weak or absent, and caregiving is possibly less mutually satisfying. Some tired or ill parents have difficulty interpreting and responding to their infants. Preterm infants and those born with congenital anomalies are often too weak to be responsive to parental cues and require special supportive nursing care. For example, infants born with heart defects tire easily during feedings. Nurses can support parental attachment by pointing out positive qualities and responses of the newborn and acknowledging how difficult the separation can be for parents and infant.

Health Promotion

Screening

Newborn screening tests are administered before babies leave the hospital to identify serious or life-threatening conditions before symptoms begin. Results of the screening tests are sent directly to the infant’s pediatrician. If a screening test suggests a problem, the baby’s physician usually follows up with further testing and may refer the infant to a specialist for treatment if needed. Blood tests help determine inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs). These are genetic disorders caused by the absence or deficiency of a substance, usually an enzyme, essential to cellular metabolism that results in abnormal protein, carbohydrate, or fat metabolism. Although IEMs are rare, they account for a significant proportion of health problems in children. Neonatal screening is done to detect phenylketonuria (PKU), hypothyroidism, galactosemia, and other diseases to allow appropriate treatment that prevents permanent mental retardation and other health problems.

The AAP recommends universal screening of newborn hearing before discharge since studies have indicated that the incidence of hearing loss is as high as 1 to 3 per 1000 normal newborns (Davidson et al., 2008). If health care providers detect the loss before 3 months of age and intervention is initiated by 6 months, children are able to achieve normal language development that matches their cognitive development through the age of 5 (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Car Seats

An essential component of discharge teaching is the use of a federally approved car seat for transporting the infant from the hospital or birthing center to home. Automobile injuries are a leading cause of death in children in the United States. Many of these deaths occur when the child is not properly restrained (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Parents need to learn how to properly fit the restraint to the infant and how to properly install the car seat. All infants and toddlers should ride in a rear-facing car safety seat until they are 2 years of age or until they reach the highest weight or height allowed by the manufacturer or their car safety seat (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011a). Placing an infant in a rear-facing restraint in the front seat of a vehicle is extremely dangerous in any vehicle with a passenger-side air bag. Nurses are responsible for providing education on the use of a car seat before discharge from the hospital.

Cribs and Sleep

Beginning June 28, 2011, new federal safety standards prohibit the manufacture or sale of drop-side rail cribs (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011b). New cribs sold in the United States must meet these governmental standards for safety, but some older cribs were manufactured before the newer requirements were instituted. Unsafe cribs should be disassembled and thrown away (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2011b). Parents also need to inspect an older crib to make sure the slats are no more than 6 cm (2.4 inches) apart. The crib mattress should fit snugly, and crib toys or mobiles should be attached firmly with no hanging strings or straps. Instruct parents to remove mobiles as soon as the infant is able to reach them (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Also consider using a portable play yard, as long as it is not a model that has been recalled.

Infant

During infancy, the period from 1 month to 1 year of age, rapid physical growth and change occur. This is the only period distinguished by such dramatic physical changes and marked development. Psychosocial developmental advances are aided by the progression from reflexive to more purposeful behavior. Interaction between infants and the environment is greater and more meaningful for the infant. During this first year of life the nurse easily observes the adaptive potential of infants because changes in growth and development occur so rapidly.

Physical Changes

Steady and proportional growth of the infant is more important than absolute growth values. Charts of normal age- and gender-related growth measurements enable the nurse to compare growth with norms for a child’s age. Measurements recorded over time are the best way to monitor growth and identify problems. Size increases rapidly during the first year of life; birth weight doubles in approximately 5 months and triples by 12 months. Height increases an average of 2.5 cm (1 inch) during each of the first 6 months and about 1.2 cm ( inch) each month until 12 months (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

inch) each month until 12 months (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Throughout the first year the infant’s vision and hearing continue to develop. Some infants as young as  months are able to link visual and auditory stimuli (Santrock, 2009). Patterns of body function also stabilize, as evidenced by predictable sleep, elimination, and feeding routines. Some reflexes that are present in the newborn such as blinking, yawning, and coughing remain throughout life; whereas others such as grasping, rooting, sucking, and the Moro or startle reflex disappear after several months.

months are able to link visual and auditory stimuli (Santrock, 2009). Patterns of body function also stabilize, as evidenced by predictable sleep, elimination, and feeding routines. Some reflexes that are present in the newborn such as blinking, yawning, and coughing remain throughout life; whereas others such as grasping, rooting, sucking, and the Moro or startle reflex disappear after several months.

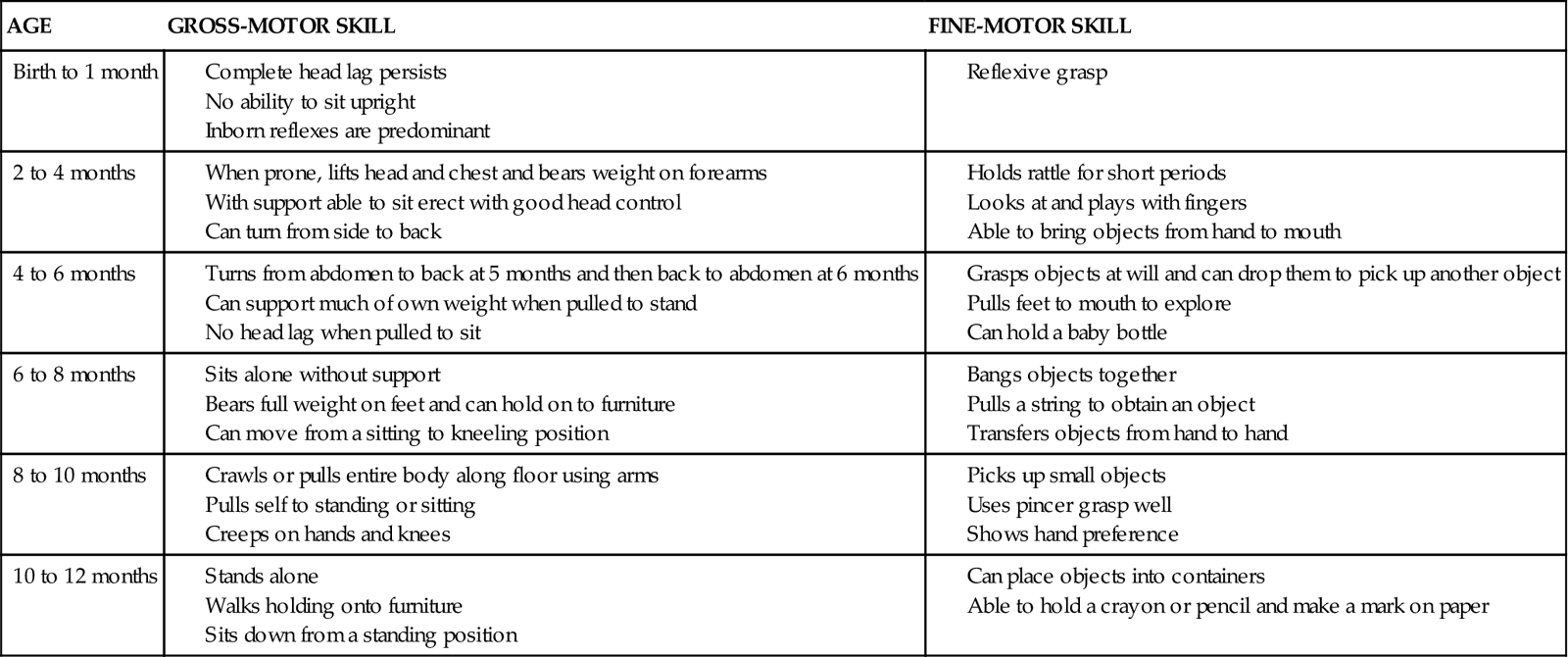

Gross-motor skills involve large muscle activities and are usually closely monitored by parents who easily report recently achieved milestones. Newborns can only momentarily hold their heads up, but by 4 months most infants have no head lag. The same rapid development is evident as infants learn to sit, stand, and then walk. Fine-motor skills involve small body movements and are more difficult to achieve than gross-motor skills. Maturation of eye-and-hand coordination occurs over the first 2 years of life as infants move from being able to grasp a rattle briefly at 2 months to drawing an arc with a pencil by 24 months. Development proceeds at a variable pace for each individual but usually follows the same pattern and within the same time frame (Table 12-1).

TABLE 12-1

Gross- and Fine-Motor Development in Infancy

| AGE | GROSS-MOTOR SKILL | FINE-MOTOR SKILL |

| Birth to 1 month | ||

| 2 to 4 months | ||

| 4 to 6 months | ||

| 6 to 8 months | ||

| 8 to 10 months | ||

| 10 to 12 months |

Adapted from Hockenberry M, Wilson D: Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 8, St Louis, 2007, Mosby; Santrock JW: Life-span development, ed 12, New York, 2008, McGraw-Hill.

Cognitive Changes

The complex brain development during the first year is demonstrated by the infant’s changing behaviors. As he or she receives stimulation through the developing senses of vision, hearing, and touch, the developing brain interprets the stimuli. Thus the infant learns by experiencing and manipulating the environment. Developing motor skills and increasing mobility expand an infant’s environment and, with developing visual and auditory skills, enhance cognitive development. For these reasons Piaget (1952) named his first stage of cognitive development, which extends until around the third birthday, the sensorimotor period. Today’s researchers have many more methods available to study the cognitive development of infants, and they believe that infants are far more competent than Piaget was able to discern by observation alone (Santrock, 2009) (see Chapter 11).

Infants need opportunities to develop and use their senses. Nurses need to evaluate the appropriateness and adequacy of these opportunities. For example, ill or hospitalized infants sometimes lack the energy to interact with their environment, thereby slowing their cognitive development. Infants need to be stimulated according to their temperament, energy, and age. The nurse uses stimulation strategies that maximize the development of infants while conserving their energy and orientation. An example of this is a nurse talking to and encouraging an infant to suck on a pacifier while administering the infant’s tube feeding.

Language

Speech is an important aspect of cognition that develops during the first year. Infants proceed from crying, cooing, and laughing to imitating sounds, comprehending the meaning of simple commands, and repeating words with knowledge of their meaning. By 1 year infants not only recognize their own names but are able to say three to five words and understand almost 100 words (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). The nurse promotes language development by encouraging parents to name objects on which their infant’s attention is focused. The nurse also assesses the infant’s language development to identify developmental delays or potential abnormalities.

Psychosocial Changes

Separation and Individuation

During their first year infants begin to differentiate themselves from others as separate beings capable of acting on their own. Initially, infants are unaware of the boundaries of self, but through repeated experiences with the environment they learn where the self ends and the external world begins. As they determine their physical boundaries, they begin to respond to others (Fig. 12-4).

Two- and 3-month-old infants begin to smile responsively rather than reflexively. Similarly they recognize differences in people when their sensory and cognitive capabilities improve. By 8 months most infants are able to differentiate a stranger from a familiar person and respond differently to the two. Close attachment to their primary caregivers, most often parents, usually occurs by this age. Infants seek out these persons for support and comfort during times of stress. The ability to distinguish self from others allows infants to interact and socialize more within their environments. For example, by 9 months infants play simple social games such as patty-cake and peek-a-boo. More complex interactive games such as hide-and-seek involving objects are possible by age 1.

Erikson (1963) describes the psychosocial developmental crisis for the infant as trust versus mistrust. He explains that the quality of parent-infant interactions determines development of trust or mistrust. The infant learns to trust self, others, and the world through the relationship between the parent and child and the care the child receives (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). During infancy the child’s temperament or behavioral style becomes apparent and influences the interactions between parent and child. You can help parents understand their child’s temperament and determine appropriate childrearing practices (see Chapter 11).

Assess the availability and appropriateness of experiences contributing to psychosocial development. Hospitalized infants often have difficulty establishing physical boundaries because of repeated bodily intrusions and painful sensations. Limiting these negative experiences and providing pleasurable sensations are interventions that support early psychosocial development. Extended separations from parents complicate the attachment process and increase the number of caregivers with whom the infant must interact. Ideally the parents provide the majority of care during hospitalization. When parents are not present, either at home or in the hospital, make an attempt to limit the number of different caregivers who have contact with the infant and to follow the parents’ directions for care. These interventions foster the infant’s continuing development of trust.

Play

Play provides opportunities for development of cognitive, social, and motor skills. Much of infant play is exploratory as infants use their senses to observe and examine their own bodies and objects of interest in their surroundings. Adults facilitate infant learning by planning activities that promote the development of milestones and providing toys that are safe for the infant to explore with the mouth and manipulate with the hands such as rattles, wooden blocks, plastic stacking rings, squeezable stuffed animals, and busy boxes.

Health Risks

Injury Prevention

Injury from motor vehicle accidents, aspiration, suffocation, falls, or poisoning is a major cause of death in children 6 to 12 months old. An understanding of the major developmental accomplishments during this time period allows for injury-prevention planning. As the child achieves gains in motor development and becomes increasingly curious about the environment, constant watchfulness and supervision are critical for injury prevention.

Child Maltreatment

Child maltreatment includes intentional physical abuse or neglect, emotional abuse or neglect, and sexual abuse (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). More children suffer from neglect than any other type of maltreatment. Children of any age can suffer from maltreatment, but the youngest are the most vulnerable. In addition, many children suffer from more than one type of maltreatment. No one profile fits a victim of maltreatment, and the signs and symptoms vary (Box 12-1).

A combination of signs and symptoms or a pattern of injury should arouse suspicion. It is important for the health care provider to be aware of certain disease processes and cultural practices. Lack of awareness of normal variants such as Mongolian spots causes the health care provider to assume that there is abuse. Children who are hospitalized for maltreatment have the same developmental needs as other children their age, and the nurse needs to support the child’s relationship with the parents (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Health Promotion

Nutrition

The quality and quantity of nutrition profoundly influences the infant’s growth and development. Many women have already selected a feeding method well before the infant’s birth, yet others will have questions for the nurse later in the pregnancy. Nurses are in a unique position to help parents select and provide a nutritionally adequate diet for their infant. Understand that factors such as support, culture, role demands, and previous experiences influence feeding methods (Davidson et al., 2008).

Breastfeeding is recommended for infant nutrition because breast milk contains the essential nutrients of protein, fats, carbohydrates, and immunoglobulins that bolster the ability to resist infection. Both the AAP and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommend human milk for the first year of life (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). However, if breastfeeding is not possible or if the parent does not desire it, an acceptable alternative is iron-fortified commercially prepared formula. Recent advances in the preparation of infant formula include the addition of nucleotides and long-chain fatty acids, which augment immune function and increase brain development. The use of whole cow’s milk, 2% cow’s milk, or alternate milk products before the age of 12 months is not recommended. The composition of whole cow’s milk can cause intestinal bleeding, anemia, and increased incidence of allergies (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

The average 1-month-old infant takes approximately 18 to 21 ounces of breast milk or formula per day. This amount increases slightly during the first 6 months and decreases after introducing solid foods. The amount of formula per feeding and the number of feedings vary among infants. The addition of solid foods is not recommended before the age of 6 months because the gastrointestinal tract is not sufficiently mature to handle these complex nutrients and infants are exposed to food antigens that produce food protein allergies. Developmentally, infants are not ready for solid food before 6 months. The extrusion (protrusion) reflex causes food to be pushed out of the mouth. The introduction of cereals, fruits, vegetables, and meats during the second 6 months of life provides iron and additional sources of vitamins. This becomes especially important when children change from breast milk or formula to whole cow’s milk after the first birthday. Solid foods should be offered one new food at a time. This allows for identification if a food causes an allergic reaction. The use of fruit juices and nonnutritive drinks such as fruit-flavored drinks or soda should be avoided since these do not provide sufficient and appropriate calories during this period (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Infants also tolerate well-cooked table foods by 1 year. The amount and frequency of feedings vary among infants; thus be sure to discuss differing feeding patterns with parents.

Supplementation

The need for dietary vitamin and mineral supplements depends on the infant’s diet. Full-term infants are born with some iron stores. The breastfed infant absorbs adequate iron from breast milk during the first 4 to 6 months of life. After 6 months iron-fortified cereal is generally an adequate supplemental source. Because iron in formula is less readily absorbed than that in breast milk, formula-fed infants need to receive iron-fortified formula throughout the first year.

Adequate concentrations of fluoride to protect against dental caries are not available in human milk; therefore fluoridated water or supplemental fluoride is generally recommended. A recent concern is the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in children that may or may not be safe. Inquire about the use of such products to help the parent determine whether or not the product is truly safe for the child (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Immunizations

The widespread use of immunizations has resulted in the dramatic decline of infectious diseases over the past 50 years and therefore is a most important factor in health promotion during childhood. Although most immunizations can be given to persons of any age, it is recommended that the administration of the primary series begin soon after birth and be completed during early childhood. Vaccines are among the safest and most reliable drugs used. Minor side effects sometimes occur; however, serious reactions are rare. Parents need instructions regarding the importance of immunizations and common side effects such as low-grade fever and local tenderness. The recommended schedule for immunizations changes as new vaccines are developed and advances are made in the field of immunology. Stay informed of the current policies and direct parents to the primary caregiver for their child’s schedule. The AAP maintains the most current schedule on their Internet website, http://www.aap.org. Research over the past three decades has clearly indicated that infants experience pain with invasive procedures (e.g., injections) and that nurses need to be aware of measures to reduce or eliminate pain with any health care procedure (see Chapter 31).

Sleep

Sleep patterns vary among infants, with many having their days and nights reversed until 3 to 4 months of age. Thus it is common for infants to sleep during the day. By 6 months most infants are nocturnal and sleep between 9 and 11 hours at night. Total daily sleep averages 15 hours. Most infants take one or two naps a day by the end of the first year. Many parents have concerns regarding their infant’s sleep patterns, especially if there is difficulty such as sleep refusal or frequent waking during the night. Carefully assesses the individual problem before suggesting interventions to address their concern.

Toddler

Toddlerhood ranges from the time children begin to walk independently until they walk and run with ease, which is from 12 to 36 months. The toddler has increasing independence bolstered by greater physical mobility and cognitive abilities. Toddlers are increasingly aware of their abilities to control and are pleased with successful efforts with this new skill. This success leads them to repeated attempts to control their environments. Unsuccessful attempts at control result in negative behavior and temper tantrums. These behaviors are most common when parents stop the initial independent action. Parents cite these as the most problematic behaviors during the toddler years and at times express frustration with trying to set consistent and firm limits while simultaneously encouraging independence. Nurses and parents can deal with the negativism by limiting the opportunities for a “no” answer. For example, the nurse does not ask the toddler, “Do you want to take your medicine now?” Instead, he or she tells the child that it is time to take medicine and offers a choice of water or juice to drink with it.

Physical Changes

The average toddler grows 6.2 cm (2.5 inches) in height and gains approximately 5 to 7 pounds each year (Santrock, 2009). The rapid development of motor skills allows the child to participate in self-care activities such as feeding, dressing, and toileting. In the beginning the toddler walks in an upright position with a broad stance and gait, protuberant abdomen, and arms out to the sides for balance. Soon the child begins to navigate stairs, using a rail or the wall to maintain balance while progressing upward, placing both feet on the same step before continuing. Success provides courage to attempt the upright mode for descending the stairs in the same manner. Locomotion skills soon include running, jumping, standing on one foot for several seconds, and kicking a ball. Most toddlers ride tricycles, climb ladders, and run well by their third birthday.

Fine-motor capabilities move from scribbling spontaneously to drawing circles and crosses accurately. By 3 years the child draws simple stick people and is usually able to stack a tower of small blocks. Children now hold crayons with their fingers rather than with their fists and can imitate vertical and horizontal strokes. They are able to manage feeding themselves with a spoon without rotating it and can drink well from a cup without spilling. Toddlers can turn pages of a book one at a time and can easily turn doorknobs (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Cognitive Changes

Toddlers increase their ability to remember events and begin to put thoughts into words at about 2 years of age. They recognize that they are separate beings from their mothers, but they are unable to assume the view of another. Toddlers reason based on their own experience of an event. They use symbols to represent objects, places, and persons. Children demonstrate this function as they imitate the behavior of another that they viewed earlier (e.g., pretend to shave like daddy), pretend that one object is another (e.g., use a finger as a gun), and use language to stand for absent objects (e.g., request bottle).

Language

The 18-month-old child uses approximately 10 words. The 24-month-old child has a vocabulary of up to 300 words and is generally able to speak in two-word sentences, although the ability to understand speech is much greater than the number of words acquired (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). “Who’s that?” and “What’s that?” are typical questions children ask during this period. Verbal expressions such as “me do it” and “that’s mine” demonstrate the 2-year-old child’s use of pronouns and desire for independence and control. By 36 months the child can use simple sentences, follow some grammatical rules, and learn to use five or six new words each day. Language development may seem to occur in early childhood, but it actually develops further into the later school years and adolescence (Santrock, 2009). Parents can facilitate language development best by talking to their children. Reading to children helps expand their vocabulary, knowledge, and imagination. Television is never used instead of parent-child interaction.

Psychosocial Changes

According to Erikson (1963) a sense of autonomy emerges during toddlerhood. Children strive for independence by using their developing muscles to do everything for themselves and become the master of their bodily functions. Their strong wills are frequently exhibited in negative behavior when caregivers attempt to direct their actions. Temper tantrums result when parental restrictions frustrate toddlers. Parents need to provide toddlers with graded independence, allowing them to do things that do not result in harm to themselves or others. For example, young toddlers who want to learn to hold their own cups often benefit from two-handled cups with spouts and plastic bibs with pockets to collect the milk that spills during the learning process.

Play

Socially toddlers remain strongly attached to their parents and fear separation from them. In their presence they feel safe, and their curiosity is evident in their exploration of the environment. The child continues to engage in solitary play during toddlerhood but also begins to participate in parallel play, which is playing beside rather than with another child. Play expands the child’s cognitive and psychosocial development. It is always important to consider if toys support development of the child, along with the safety of the toy.

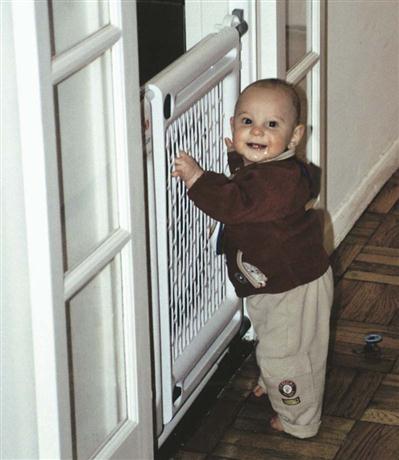

Health Risks

The newly developed locomotion abilities and insatiable curiosity of toddlers make them at risk for injury. Toddlers need close supervision at all times and particularly when in environments that are not childproofed (Fig. 12-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree