Chapter 6 Complex community-based initiatives

Introduction

In recent years much has been made of new ways of working in the community to deal with the issues of social exclusion, particularly in isolated, under-resourced areas of the UK. Improving health and t-ackling inequalities by narrowing the gap between social groups has been regarded as a key aspect of New Labour policy (Hunter 2004). One method of achieving this has been to develop community-based initiatives supported by substantial government funding (Hills 2004).

These complex community-based initiatives (CCIs) have been defined as: neighbourhood-based agencies, for local people, employing both lay and professional workers with the aim of providing sustained goal-oriented home (outreach) and centre-based services that offer ‘information, guidance and feedback, joint-problem-solving, help with securing entitlements and services, encouragement, and psychological support’ (Halpern 1990, p. 470).

Beyond this it was also acknowledged that CCIs varied in size, shape and aims. However, they all had one main goal and that was to promote positive change in the ‘individual, family and community circumstances in disadvantaged neighbourhoods by improving physical, economic and social conditions’ Kubisch et al (1995, p. 1). These various elements within a CCI were supposed to be delivered in a devolved way, synergistically offered by different agencies working together across a variety of spheres. This could be: youth development, centre and home-based family support, community planning, housing and benefit support, job training, adult education, mental health care, economic development and employment readiness, life opportunity activities and child-care with many programmes using cross-agency funding to extend these elements inventively.

Policy

Inequality has been described in the literature as ‘two, three or even fourfold differences in death rates between social classes’ (Wilkinson 1996). Between 1979 and 1997 health inequalities were not raised at all at policy level (Neuberger 2003). Proactive community-based prevention work was a low priority area for government policy development. The Acheson Independent Inquiry (Department of Health (DH) 1998) acted as a kick-start to the incoming Labour administration regarding the inequality debate. The ideal of prevention was resurrected and some importance given to implementation through the role of community-based workers, such as health visitors. The 39 recommendations from the report gave the New Labour administration three priority areas regarded as crucial to improve the health of the less well-off:

Government had recognised that improving the nations’ health and narrowing the widening gap between social groups provided a challenge in policy making that exceeded any single government department’s responsibilities (Hunter 2004). However, there continued to be a focus on ‘downstream’ issues that gave priority to secondary and acute care rather than the more ‘upstream’ public health focused, determinants of health issues.

Public health has had a low profile in the UK because of: 1) the power of the medical profession to drive forward a focus on the curative role; 2) the creation of an NHS resolute on the priority of resourcing the acute hospitals; and 3) a scarcity of evidence demonstrating the benefits of public health interventions (Neuberger 2003).

Following the Acheson Inquiry (DH 1998), four types of cross-government in-itiatives (Neuberger 2003) were developed:

Why bother developing a public health approach or initiating a CCI? Part of the impetus from the government perspective was economic because safer, healthier communities are good for the economy and this prevents a continuing rise in demand for illness services as well as higher rates of absenteeism from work (Neuberger 2003). From an economic perspective, healthy communities attract investment, venture capital and speculation while unhealthy areas don’t (Hunter 2004). Wanless (HM Treasury 2004b) added impetus to the process by stating that better public health initiatives significantly impact on the demand for health services. He was concerned that too much emphasis went into ‘downstream’ NHS acute care provision rather than focusing on ‘upstream’ initiatives that would improve and sustain health. The population, Wanless suggested, had to be health literate with availability of more useful advice and education so that they could be enabled to make informed choices about their life and their health. A public health approach had the capacity to save the government £30 billion by 2022 (Hunter 2004) because it would keep the focus on a proactive preventive approach to service delivery encouraging wellness maintenance rather than illness support. However, this issue is complex and it has been suggested that it is inadequate to take some of the worst off out of poverty and then assume that inequalities in health will be reduced (Shaw et al 2005).

Sure Start: a CCI

Sure Start (Department of Education and Employment 1999) was a national programme, initially available in England, then rolled out later to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Information on the slightly different expectations in the four parts of the UK can be accessed via the Sure Start website (see resources list for further information on Sure Start). Like many other CCIs it was designed to tackle the roots of disadvantage and inequity, by addressing policy to prevent social exclusion (Roberts 2000). Sure Start centred its resources and support at the start of life and followed government monitoring, target and evaluation mechanisms (Houston 2003a, 2003b). A special policy team (The Sure Start Unit) managed the new community system, both policy and strategy.

Before any programme is set up to be preventive it is necessary to have an understanding of the phenomena that are to be prevented, and to understand the political elements and the unintended consequences of managing the prevention strategy (Sinclair et al 1997). Early childhood complex community-based initiatives were developed in 1964 in the USA specifically to enrich the pre-school environment and to enhance the development of infants and toddlers with the aim of ‘closing the gap between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers by raising poor children’s levels of social and educational competence’ (Brookes-Gunn et al 1994, p. 924).

Many of these new community-based organisations brought with them new management systems that existing community structures, both statutory and voluntary, had to somehow plug into. For example, Sure Start and Local Strategic Partnerships (LSP) had many elements in common in their neighbourhood approach. The community-based intervention process for LSP and Sure Start involved developing: a management board structure, often with an executive; a community or parent forum and task-based groupings for topic areas, for example, a Family Support Team (Sure Start) or community safety task group in the LSP structure (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister 2004).

Sure Start as a CCI was based in post-code bounded areas defined as deprived (Department of Education and Employment 1999). Parents who had a child in the 0–4 age group and who were resident in the defined area could access the local programme. Socially impoverished neighbourhoods tend to operate on a scarcity economy, there may be fear of exploitation, or of being beholden to others (Garbarino & Ganzel 2000). Those on the very edge of the margins are socially excluded from the community, reciprocity is distrusted, and neighbourliness fails to flourish. Countering this, with a remit of social inclusion, the Sure Start CCI focus was to be on four main over-arching aspects:

Table 6.1 Sure Start aims at government level

| Aim | Provision |

|---|---|

| Better access to early education and play | Two generational (involve parents as well as children) |

| Use of evidence-based practice | Non-stigmatising (avoid the label ‘problem families’) |

| Better health services for children | Multi-faceted in approach (education as well as health) |

| Increased support and advice on family issues | Persistent (last long enough to make a difference) |

| Empowered communities where change is locally led (by parents) |

Table 6.2 Sure Start at government level

| Objectives | Themed areas |

|---|---|

(from DH 2002)

Against a backdrop of international commitment to early years development, UK government planning from 1997 onwards, particularly in the wake of the Acheson Report (DH 1998), involved: children’s services, remediation of child poverty and family support (HM Treasury 2004a, Lloyd 2000, Wainwright 1999). Additionally there was a focus on equality of opportunity to paid employment, education and training (Wainwright 1999). In poor neighbourhoods the type of support from family, friends and services is more likely to be fragmented, narrow and difficult to access (Hanson & Carta 1995). Sure Start would counter this by providing care that was:

A substantial amount of research existed, including a ‘review of reviews’ demonstrating that early intervention benefited disadvantaged and ‘at-risk’ children, improving cognitive, language, motor and socio-emotional development as well as improving family functioning (Casto & Mastropeiri 1986). Results from the methodologically strongest studies also demonstrated substantial positive long-term effects from early childhood intervention support that were able to go beyond baseline measurement techniques (Gomby et al 1995).

A key feature of the UK government’s approach was that ‘joined-up’ social problems demanded ‘joined-up’ solutions (Hunter 2004). Sure Start would have the support of the:

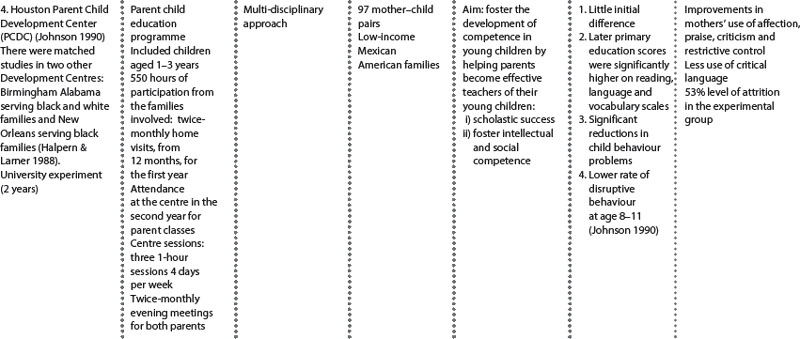

The government promoted public health through a proactive interventionist approach aimed at helping families and communities, particularly in deprived areas. The role of Sure Start (Table 6.1 and 6.2) within the existing pre-school UK structure was to enhance, develop and support organisations in the community already offering pre-school activity. Sure Start was also charged with developing more and better childcare facilities, e.g. crèche support, to allow parents to train and to return to the workforce as part of an employability anti-poverty drive. Good-quality, out-of-home day care for children has been shown to have a positive impact on the cognitive development of the child (Campbell & Ramey 1994, Schweinhart 2003, Schweinhart et al 1993).

Stress and social support are ecological influences that impact on parenting and child development, particularly in high-risk populations. Informal professional support was positively linked to increased maternal satisfaction with parenting (Crnic et al 1986) and the level of support offered to parents during the first 2 years of life was a predictor of the child’s increased cognitive functioning at aged 5 years (Crnic & Stormshak 1997).

Ongoing policy commitment to a child-centred approach

In the late 1990s, government policy demonstrated strong commitment to community, family and child-focused policy initiatives. Documents such as Every child matters (Department for Education and Skills 2004) supported early intervention to support parents alongside professional integration and ‘joined-up’ services. The policy aim was:

‘The government has built the foundations for improving these outcomes through Sure Start’

(Department for Education and Skill 2004: section 11).

The aim of improving the lives and health of children and pregnant women was part of the recent policy strategy; this would be done by setting standards for health and local authority service provision (DH 2004). In the new standard-setting – National Service Framework for Children Young People and Maternity Services (DH 2004) (see additional resources list), there were to be a number of elements aimed at better integration and co-ordination between agencies:

Explaining the complexity of CCIs

Part of the complexity within these community systems is ‘vertical’: attempting to make change at individual, family and community levels and pre-supposing that interaction between these three levels already exists (Kubisch et al 1995). Community-based interventions are ‘heterogeneous and complex’ and are, therefore, about creating a shift of rationale from a top-down professional agenda to a bottom-up community involvement approach (Hills 2004). Additionally, a ‘horizontal’ complexity can be created by bringing statutory and voluntary organisations into the new structure, along with their own management systems (e.g. in Sure Start) where each partner organisation manages workers that they ‘second’ into the new system:

This complexity within CCIs has been examined to reveal a number of important issues such as:

The complexity of the many-levelled, multi-layered structure leads to lack of clarity about what is being evaluated and, therefore, difficulty in establishing any link between the input and output (Hills 2004).

Seven further degrees of complexity (from the findings of Health Action Zones) have been highlighted (Barnes et al 2003):

Finally, Judge and Bauld (2001, p. 24), from the viewpoint of evaluating Health Action Zones, stated that complex community-based initiatives have multiple broad goals:

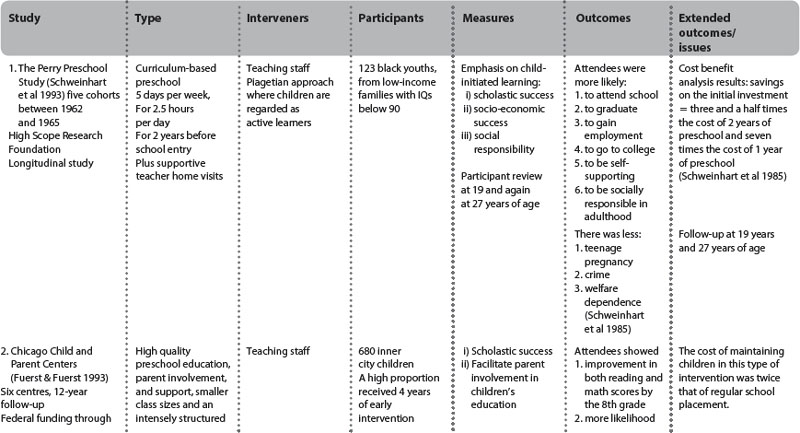

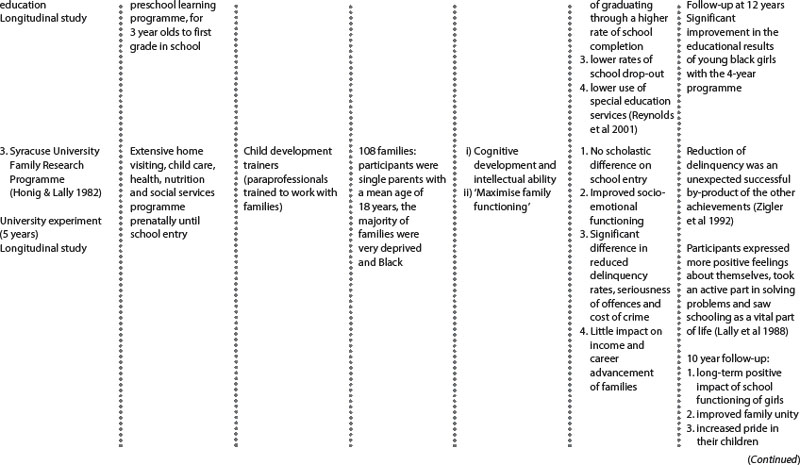

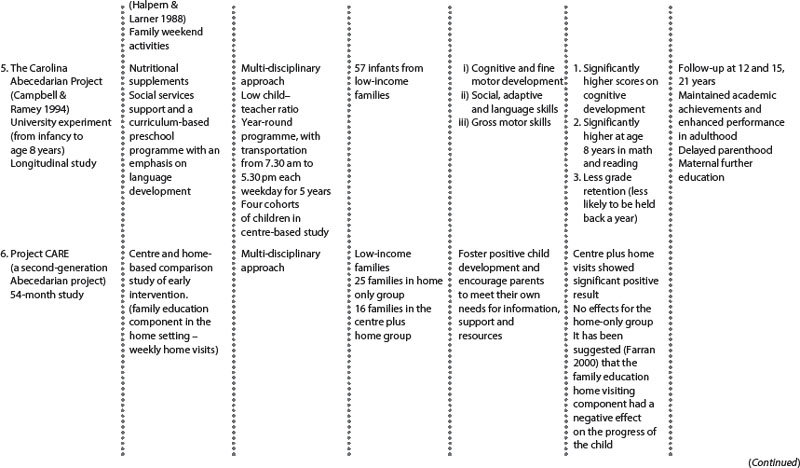

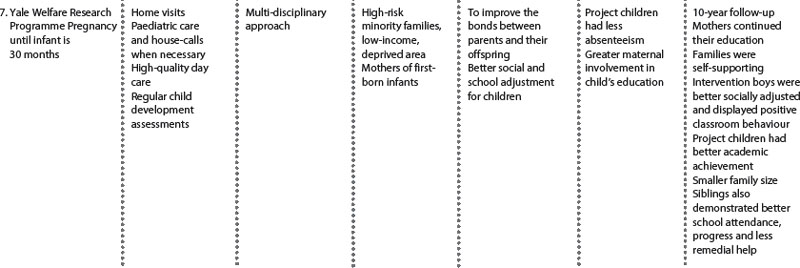

This complexity of the system results in a process that is ‘more value driven than evidence based’ (Coote 2003, p. 16). Experience (from US-based CCIs) identified that agreeing upon long-term outcomes was straightforward because they are often broad and uncontroversial. The interim outcomes pose more difficulty because both scientific and experiential knowledge about the links between early, intermediate and long-term outcomes is undeveloped in the area of complex interventions. The hardest part of the process is in defining interim activities and outcomes and then being able to link those aspects to the longer-term outcomes (Connell & Kubisch 1998). Table 6.3 demonstrated this issue by showing some of the unexpected long-term outcomes in the longitudinal follow-up of US CCIs, and additionally some of the failures of high early input with poor longer-term outcomes; both features examined in depth elsewhere (Karoly et al 1998).

Re-orienting community-based services was about developing collaboration between the statutory, voluntary and community sectors (Heenan 2004). Providing multi-faceted services in UK CCIs was also about targeting the wider determinants of health at a local level by providing new mechanisms to reach out to the excluded or marginalised in the community, such as HAZ, Sure Start or Healthy Living Centres. Additionally, the focus was on altering access to services for those most in need to assist their health improvement. These structures provided opportunities for: 1) local consultation processes; 2) improved gateways to information and advice on benefits, welfare and employment; and 3) re-designing local health services to enable people to engage in building and sustaining the capacity of their own local community.

As inequalities endured, with a growing gap between rich and poor, the disparity between those with different amounts of ‘potential’ for good health was highlighted (Bartley 2004). Without help, some were destined to lead a less privileged, socially excluded life. Could CCI programmes developed within the informal local system in the community (such as Sure Start or HAZ) help and somehow confer on people an ‘ability to manage their consumption, leisure and use of health services in a more health-promoting manner’ (Bartley 2004, p. 10).

Examples from practice Sure Start: 1

This study example from practice addressed quantitative measurement and qualitative approaches to access local information from consumers about changed service provision. The ‘traditional’ community midwifery service was changed to a Sure Start Service (with some supportive local midwifery service NHS Trust funding) to a new 24-hour, 7 days a week midwifery service provided by five dedicated Sure Start midwives who were also involved in running a breastfeeding Baby Café and providing proactive advice, support and information (Houston & Bennett 2004).

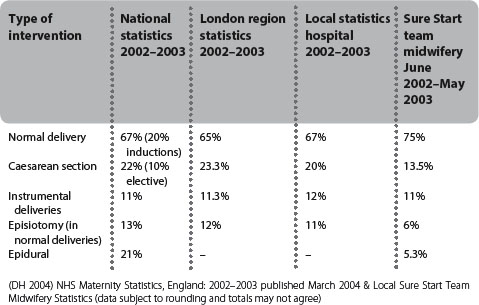

Tables 6.4 and 6.5 illustrate the difference made to the community by the impact of Sure Start team midwifery in one area. The national and regional stat-istics show a consistently high caesarean section and instrumental delivery rate in comparison with the team midwifery approach. Comparison of pre-Sure-Start area statistics with post-Sure-Start data showed a trend towards lower rates in caesarean section, instrumental delivery and episiotomy with a corresponding positive increase in the level of normal delivery.

Table 6.5 Comparison of local Sure Start area statistics

| Type of intervention | Sure Start area/pre-Sure Start June 2001–May 2002 | Sure Start team midwifery June 2002–May 2003 |

|---|---|---|

| Normal delivery | 69.5% | 75% |

| Caesarean section | 16.5% | 13.5% |

| Instrumental deliveries | 14% | 11% |

| Episiotomy (in normal deliveries) | 9.2% | 6% |

| Epidural | 18.2% | 5.3% |

Additionally, qualitative responses were examined in detail in order to make further changes to the new system after it had been running for the first year. One client summed up the meaning of the change echoed by many on the new Sure Start system:

Examples from practice in Sure Start: 2

The documentary analysis (Houston & Parker 2005) addressed specific factors that could be used as a comparator in some ways between what had existed before and the new CCI Sure Start system. The factors highlighted were:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree