CHAPTER 6 Community care for older Australians

issues and future directions

FRAMEWORK

This chapter gives an excellent overview of the Australian Government community service system. It adds to the content of Chapter 1 and expands the reader’s knowledge on the current structure and need for change. The non-government sector also has a large role in providing community care but is mostly funded by the Australian Government. Unravelling the complex streams of care is a daunting task for the public, and especially for older people. The input from state and territory governments is also complex and causes various system clashes in terms of flexibility of service provision. Part of the new Labour Government’s agenda is to include provision for social inclusiveness and active ageing. This is a positive step and will lead to extensive changes over time in the way the system works. The authors recognise the major contribution of family, partners and volunteer community carers in the informal maintenance of older people in the community. Emerging new trends and directions will alter the whole nature of care for the older person in the future. [RN, SG]

Introduction

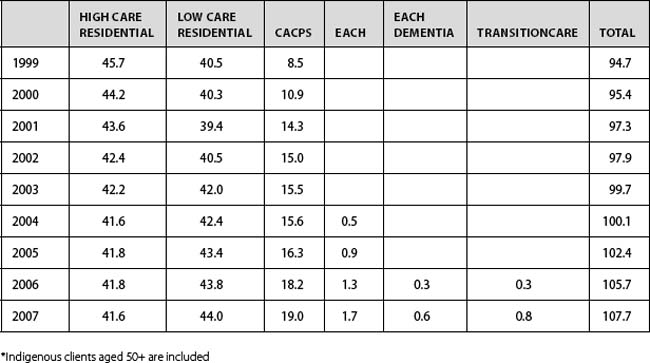

Community care encompasses a very wide range of sources of support that assist older adults. It includes informal and formal care, GPs and dental services, broad community health, allied health, pharmacists, preventative programs and education, as well as those programs funded by Australian and state governments to provide community care. These programs include Home and Community Care (HACC) services, Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs), the Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) program, the EACH Dementia program, the Transition Care Program (TCP), and Veterans’ Home Care (VHC). They also include assessment through the Aged Care Assessment Program (ACAP). Finally, hospitals also play a role in community care — for example, rehabilitation and discharge planning — and a range of programs assist people at the interface between acute care and the community, such as Transition Care and, in Victoria, the Hospital At Risk Program (HARP).

Background: an overview of the Australian community service system

The Australian aged care system is characterised by a mix of types of provision and a high degree of cooperation between all levels of government, service providers and the community (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare [AIHW] 2007). The non-government sector has a long history in the provision of aged care and continues to provide the majority of residential aged care services as well as community care services. Private sector involvement in aged care is mostly through high care residential services.

Although residential care continues to receive the bulk of funding (about 69% of the 8.4 billion Australian dollars spent in 2006–07 on aged and community care; Productivity Commission 2008), a shift in funding towards community care has occurred and is likely to continue in the future.

Funding, programs, growth

Demand for services

Services provided under the HACC program include domestic assistance and home maintenance, personal care, food services, respite care, transport, allied health care and community nursing. Over 68% of the program’s recipients are aged 70 years or over, but the program is also an important source of community care for younger people with a disability and their carers, with nearly 12% of recipients aged under 50 years (Productivity Commission 2008). Total government expenditure on HACC was $1.5 billion in 2006–07, comprising $928.4 million (61.9%) from the Australian Government and $595.7 million from state and territory governments (Productivity Commission 2008).

A development agenda

A new Australian Government was elected in November 2007. The recently installed Labour Government has committed to a greater focus on positive and

active ageing as part of its agenda to promote social inclusion and reduce social isolation. Helping older people maintain their independence whilst staying connected to the community has been identified as key policy principle. This focus, together with the system developments outlined above, suggest that the community aged care sector will be significantly remodelled in Australia over the next few years.

Carers and the interface between formal and informal care

Formal, publicly funded services represent only a small proportion of total assistance provided to frail older people. Extended family and partners are the largest source of emotional, practical and financial support for older people; more than 90% of older people living in the community in 2003 who required help with self-care, mobility or communication received assistance from informal care networks of family, friends and neighbours (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2004). Many people receive assistance from both formal aged care services and informal sources.

Currently, governments recognise the essential support provided to older people by carers. In Australia, the essential role of informal carers in assisting older people to remain in the community is recognised through the provision of HACC services to carers and services such as the National Respite for Carers Program (NRCP). The NRCP provides community respite services and is funded by the Australian Government. Expenditure on this program was $166.9 million in 2006–07. The NRCP assisted nearly 130 000 people in 2006–07 (Productivity Commission 2008).

The literature on long-term care for the older population has focused on trade-offs among different types of personal care in order to address the ‘woodwork effect’; that is, the concern that public coverage for home care could cause a reduction in informal care (Agree et al 2005). However, studies have generally found that formal home care does not substitute for (or crowd out) informal care and, in many cases, may supplement informal care (Kemper et al 1987; Tennstedt et al 1996). Cohen, Weinrobe and Miller (2000), in a North American study of informal carers, found that whether or not formal care substitutes for informal care is related to the characteristics of the caregiver. For adult children formal care may substitute for informal care, but this is not generally the case for spouses. Where the informal caregiver provides 8 hours per week or less of help with activities of daily living (ADL), paid help also tends to be low, but where the informal caregiver is providing large amounts of ADL help, paid help is also used for large blocks of time. Increasing the provision of community care has been suggested as a measure to encourage workforce participation in women who are currently providing informal care outside of the household (Viitanen 2007).

Tensions and pressures

Population

As with many western nations, our dramatically ageing population poses significant challenges for governments (World Health Organization [WHO] 2002). The large baby boom generation is ageing and the number of older people is projected to increase rapidly. As the youngest of the surviving baby boomers reaches 65 years of age in 2031, the population aged 65 years and over is projected to reach 5.4 million (more than double the number in 1999) and will represent 22% of the total population (compared with 12% in 1999). As the youngest baby boomers reach 85 years of age in 2051, importantly, the population aged 85 years and over is projected to reach 1.3 million (more than five times the number in 1999) and to represent 5% of the total population (Trewin 2001).

In some countries, this increasing demand has resulted in longer waiting lists for clients assessed as having low-level care needs. This is cause for concern, as research has suggested that risk may be imposed on clients if delivery of small amounts of critical services — targeted at clients at the time need is expressed — is delayed, or if services are not available at all (Elkan et al 2001; LaPlante et al 2004). If people with lower level needs are neglected, the opportunity to provide restorative services, at a time when clients are likely to retain sufficient capacity to maximally benefit, may be lost. It should be noted that a person’s ‘need’ for services is related not just to their level of functional dependence, but is also strongly affected by their circumstances, especially the extent to which they have support from their family and community.

The steadily rising demand for services also continues to place pressure on many traditional community care providers to maintain services, sometimes over many years — for example, the provision of domestic services or meals on wheels — to all eligible clients in the community (Howe et al 2006; Parker 2001; Pilkington 2006). In some countries, this has resulted in longer waiting lists or cessation of service for those clients assessed as having low-level care needs.

New models of ageing and community expectations of community care

Successful ageing

A key concept that has emerged in attempting to rethink how to address the needs and maximise the health and wellbeing of our ageing population is that of ‘successful ageing’ (Browning & Kendig 2003, 2004). Impetus for a conceptual shift towards more active, restorative models of care is mirrored by conceptual developments that have occurred within gerontology about what constitutes successful ageing.

Conceptually, the WHO definition of active ageing comprises three key pillars:

While the quality of the ageing experience will be determined by all three key pillars, there is some ongoing dispute about their relative importance. The West Australian Active Ageing Taskforce has suggested that participation, not health, should be the central pillar of the model. They also suggested that engagement in social and family connections should be placed under the participation pillar rather than the health pillar (Government of Western Australia 2003). Some recent Australian survey findings on older people’s perceptions of what constitutes successful ageing are consistent with the Western Australian perspective; that participation, including participation in social activities, is central to older adults’ views of what constitutes successful ageing (Buys & Miller 2006).

Community expectations

A growing number of critics have suggested that community care programs in Australia are not as successful as they could be because they rely on an outdated ‘dependency’ model of service provision rather than a newer focus on activity, independence and successful ageing (Baker et al 2001; Baker 2006; Glendinning et al 2008; Hallberg & Kristensson 2004; Kane 1999; Lewin et al 2006; O’Connell 2006). Current approaches often lack an emphasis on the promotion of healthy lifestyles and daily routines, social support, exercise, and autonomy and control, despite strong evidence that these are strongly linked to the maintenance of health and independence in older adults (Peel et al 2004; Seeman & Crimmins 2001; Stuck et al 1999).

Most approaches to community care provision give insufficient attention to an individual’s rehabilitative potential, and, via well-meaning attempts to substitute function with assistance, may result in a premature reduction in important physical and social activities (e.g. shopping and cooking). Older people may become entrenched in a ‘sick role’, characterised by an absence of self-motivation, and the view that because they are aged or unwell they must remain dependent upon continuous professional management of care (Baltes 1996; O’Connell 2006; Verbrugge & Jette 1994). The funding mechanisms that underpin many services also limit the capacity for services to provide restorative care. Many services are funded for short, task-focused events (e.g., ‘please provide one hour of domestic cleaning’), which makes it difficult to use a flexible, goal-oriented approach that would underpin a more restorative program (e.g., ‘please help this client to purchase and use a light-weight vacuum cleaner’; Ware 2002). Some staff may also believe that bed rest is beneficial for a frail or sick older individual, despite considerable evidence to the contrary (Baker 2006). Staff may exacerbate this situation by emphasising task completion and doing as much as they can for the client, rather than trying to assist the client to do things for themselves.

Current practice within community care services for frail older adults also contrasts sharply with the highly progressive movements that have occurred with other groups in developed countries over the previous 50 years. These movements include the concepts of normalisation and social role valorisation, which transformed approaches to the management of intellectual disability (Wolfensberger 1972), the large-scale deinstitutionalisation of people with psychiatric and intellectual disabilities, and emergence of more flexible community management models (Killaspy 2006; Mansell 2006), and, more recently, the chronic disease self-management movement from the US (e.g., Chodosh et al 2005). Older adults have not been entitled to the same ‘empowerment-oriented’ and independence-focused approaches as other groups with disabilities. As the highly educated and proactive baby boomer generation begins to enter retirement age, criticism of outmoded approaches is likely to intensify.

Future availability of carers

In the 1990s, considerable concern was expressed about the future availability of carers for frail older people. Reasons for anticipating a potential decline in informal care include declines in family size (Clarke 1995) and the proportion of older people who live with their children (Grundy 1995); rises in divorce rates (Clarke 1995), childlessness (Evandrou 1998) and employment rates among married women (Doty 1986); and changes in the care preferences of older people (Phillipson 1992; West et al 1984) and the nature of kinship obligations, especially in relation to filial responsibilities (Finch 1995).

Emerging directions in service reform

Targeting

Definitions of targeting

The focus of discussion on targeting is usually at the individual client level. However, some decisions about resource allocation are also made at other levels as funds move from government to provider organisations in different regions, and from organisations to services (NARI & BECC 1999). These levels of decision making shape the level and mix of services that can ultimately be allocated to clients and carers. Decisions made by providers about allocating resources in smaller or larger amounts to one or another individual client cannot be considered in isolation from the other levels of decision making. Even at the individual client level, resource allocation decisions are not one-off, but repeated as the client moves along the pathway from initial eligibility for service, to assessment and care planning, possible review and re-assessment, to eventual discharge when the service is no longer needed or because of a change in care arrangements, including moves to residential care (NARI & BECC 1999). The current definition of the target population eligible for HACC services is very broad, and only a proportion of those within the target population seek and gain access to services (Howe et al 2006).

What does the literature say about targeting?

More convincing evidence of the effectiveness of community care began to emerge from a modelling exercise using data from the channelling demonstration (Greene et al 1995). The authors argued that much of the failure to find convincing evidence for the efficacy of community care was due to design shortcomings in most of the earlier evaluations, particularly the failure to disaggregate the effects of particular kinds of services for particular groups of clients. Green et al went on to develop a transition probability model and used data from the channelling projects to show that more effective outcomes could have been achieved with different distribution of the same resources.

The purpose of provision of community care has generally been cast primarily in terms of reducing use of residential care. However, some authors (Benjamin 1999; Bishop 1999; Kane 1999; Stone 1999) have proposed a much wider range of goals at individual, familial and societal levels. Feldman (1999) consolidated these into lists of 10 individual-level goals and 13 societal-level goals, and commented that there are possible inconsistencies and trade-offs between these multiple goals.

The most recent formulation of the targeting debate in the US was set out in 2003 by Weissert and colleagues (1988, 2003). Weissert analysed home and community care in the US over more than three decades, discussed several longstanding shortcomings in existing targeting policy, and proposed an alternative called ‘titrating’. This model suggests that simple ‘in or out’ targeting should be replaced with an approach that takes account of the risk (R) of adverse outcomes, the effectiveness (E) of home care services in mitigating the risks and the value (V) of the outcomes achieved relative to those avoided. The ERV model calls for titrating care rather than targeting clients. The proposed titrating model would be generous in eligibility — that is, access to services would be relatively easy — but the number of resources actually allocated to each client would be carefully calibrated. The ERV model does not deny any services to low-dependency clients, but allocates more services to high dependency clients only when the additional inputs will achieve a cost-effective reduction in risk of an adverse outcome.

The Australian aged care system is characterised by a mix of types of provision and a high degree of cooperation between all levels of government, service providers and the community.

The Australian aged care system is characterised by a mix of types of provision and a high degree of cooperation between all levels of government, service providers and the community. The Australian Government has the major role of funding both residential aged care services and aged care packages in the community.

The Australian Government has the major role of funding both residential aged care services and aged care packages in the community.

Extended family and partners are the largest source of emotional, practical and financial support for older people.

Extended family and partners are the largest source of emotional, practical and financial support for older people. A gulf may develop between the ways in which families perceive the task of care provision for someone who is sick or disabled and the way in which professional carers approach the task.

A gulf may develop between the ways in which families perceive the task of care provision for someone who is sick or disabled and the way in which professional carers approach the task. A person’s ‘need’ for services is related not just to their level of functional dependence, but is also strongly affected by their circumstances, especially the extent to which they have support from their family and community.

A person’s ‘need’ for services is related not just to their level of functional dependence, but is also strongly affected by their circumstances, especially the extent to which they have support from their family and community. The focus is now much more on the promotion of activity and active participation in society in order to maximise physical and mental wellbeing.

The focus is now much more on the promotion of activity and active participation in society in order to maximise physical and mental wellbeing. Most approaches to community care provision give insufficient attention to an individual’s rehabilitative potential.

Most approaches to community care provision give insufficient attention to an individual’s rehabilitative potential. Robust evidence from diverse studies shows that small amounts of service, provided early, are worthwhile.

Robust evidence from diverse studies shows that small amounts of service, provided early, are worthwhile.